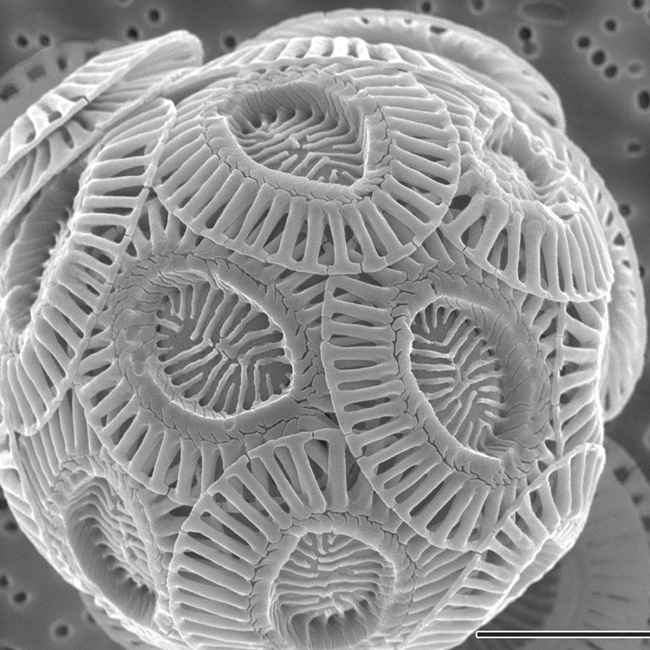

Coccolithophores, photosynthetic unicellular algae

Coccolithophores are some of the most important organisms that you have never heard of!! They are very small marine organisms who have a very significant impact on earth’s geology and ecology. They are distinctive because they have a coating that consists of a number of ornate calcium carbonate plates.

Phylogeny and taxonomy

Coccolithophores are closely related to a group of organisms (Haptophytes) that lack the plates. These two groups, together with some other organisms, have been classified a number of different ways. In a five-kingdom classification they are considered to be in the phylum Haptophyta in the kingdom Protista. The coccolithophores are sometimes considered members of the ‘golden algae’ group and some treatments lump ‘golden algae’ (haptophytes including coccolithophores and other groups), brown algae and diatoms together in a group called ‘Stramenopiles’, largely on the basis of pigments. Other workers feel that the pigmentation similarity is an artifact of two independent secondary symbiotic events.

Structure

The distinguishing feature of haptophytes is a flagellum-like structure called a haptonema that is distinct from a flagellum due to a different microtubule structure. Most members of this group also have two flagella. Within the Haptophyta, the coccolithophores are distinguished by having an outside boundary of overlapping calcium carbonate plates / shields, called coccoliths. Because they are made of calcium carbonate, coccoliths represent a ‘sink’ for carbon dioxide: the carbon to form them is derived from dissolved carbonate ions, which are (generally) derived from dissolved carbon dioxide, which (generally) is derived from respiring organisms, either aquatic or terrestrial. What happens to the coccoliths when the organism dies depends on conditions. Under certain conditions they dissolve back into solution, under other conditions they sink to the ocean floor and can form deposits hundreds of meters thick. Such deposits form the dramatic ‘white cliffs of Dover’ and the Alabaster Coast of Normandy.

Reproduction

The primary means of reproduction is asexual cell division. Since both haploid and diploid forms are found, the assumption is that they can undergo the sexual cycle but neither syngamy nor meiosis has been observed. It is believed that some members show a heteromorphic alternation of generations with a diploid, planktonic flagellate stage and a haploid, filamentous stage.

Matter and Energy

Most members of the group are photosynthetic and autotrophic but some members lack pigments and are heterotrophs; and many of the photosynthetic forms appear capable of absorbing organic material as well as synthesizing it. They are significant in being tolerant of low nutrient conditions and are found in the open oceans where nutrient supplies are very low.

Interactions

Coccoliths are tremendously important in a number of ways:

- they are the main photosynthetic forms of the open ocean and make a significant contribution to the oxygen production that most forms of life require

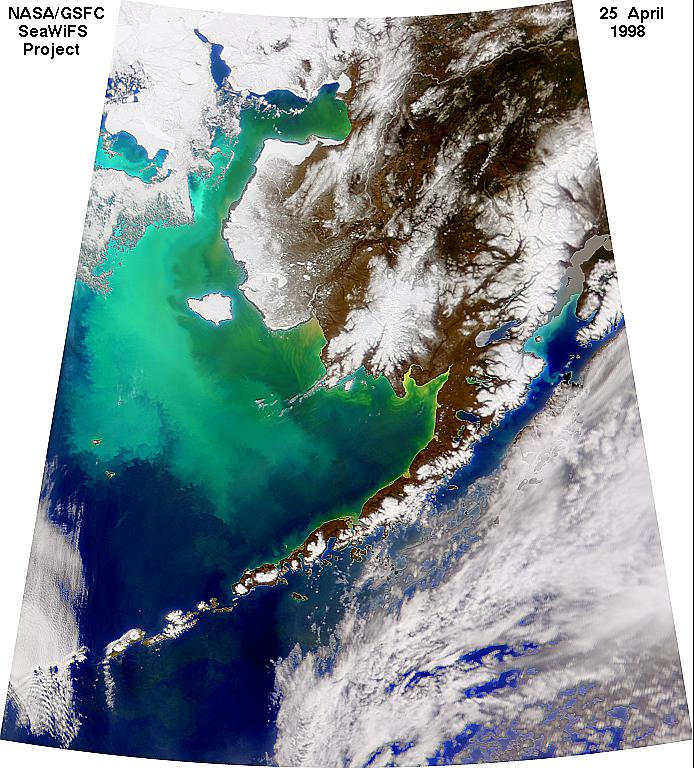

- they can remove carbon from ocean waters by forming coccoliths that can sink to the ocean floor and form geological deposits

- their optical properties can change water albedo and thereby ocean temperatures

- they produce sulfur compounds that are metabolized by bacteria to dimethylsulfide, DMS, that can influence cloud formation and acid rain (see also dinoflagellates, who also produce the same chemical)

- they serve as a food source for a number of other organisms

- they can form toxic algal blooms

Further Reading and Viewing

- “Emiliania huxleyi” by Tobey Tyrrell

- “Emiliana” on Microbe Wiki

Media Attributions

- Emiliania huxleyi coccolithophore © Alison R. Taylor (University of North Carolina Wilmington Microscopy Facility) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- White Cliffs of Dover © Immanuel Giel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Coccolithophore bloom © SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE is licensed under a Public Domain license