Open Pedagogy as Open Student Projects

Harnessing the Power of Student-Created Content: Faculty and Librarians Collaborating in the Open Educational Environment

Bryan James McGeary; Ashwini Ganeshan; and Christopher S. Guder

Authors

- Bryan James McGeary, Pennsylvania State University

- Ashwini Ganeshan, Ohio University

- Christopher S. Guder, Ohio University

Project Overview

Institution: Ohio University

Institution Type: public, research, undergraduate, postgraduate

Project Discipline: Hispanic Linguistics

Project Outcome: student-created textbook

Tools Used: Pressbooks, Institutional Repository

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Sample Assignments

- Sample Illustrations

2020 Preface

Reflecting on how devastating national events have affected higher education and U.S. society in 2020, we recognize the continued importance of open education and open pedagogy as a means of ensuring equitable access to education and shedding light on racial, social, and economic inequities in our society. As higher education moved to remote learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, open education has gained interest from administrators, faculty, and students who are looking for ways to cope with that shift. Likewise, tragedies, such as the continued killings of black people, the racist and xenophobic violence against people of Asian descent, and the ongoing destruction to Native American lands, lives, and communities, have brought issues of structural racism to the forefront of the national conversation, making it clear that there is an urgent need to design courses and textbooks in ways that foreground and center social justice issues. Open education can respond to these needs in ways that traditional textbooks typically have not by making it possible to revise content to reflect the current moment as well as surface and support marginalized voices. Moreover, the use of open educational practices to provide students with the opportunity to delve into these topics themselves, assess them, and write about them could present a way to demonstrate meaningful, active allyship. We also believe that libraries should continue to engage in this type of work with faculty and students, as it demonstrates the continued relevance of the library profession to the mission of higher education.

—Bryan, Ashwini, & Chris

For several years Ohio University Libraries have attempted to build relationships with faculty interested in using or creating open educational resources (OER). Strategies for this included a workshop series on open textbooks, focus groups on OER creation, and the purchase of an institutional repository. Additionally, two librarians and a faculty member applied for and received an internal Ohio University grant, administered by the Libraries, to support local OER creation on campus, determine the needs of faculty creating OERs, and ascertain how these projects impact the undergraduate experience. The Libraries use this grant to hire student assistants to work on faculty OER projects and to pay for technology needed to publish and share these projects with a wider audience. Through this grant two faculty members are currently leading student-developed projects that use open pedagogy to fill a void in terms of available course texts and ancillaries by directly involving students in the creation of those materials. In this chapter we describe one of those projects, a purely student-generated textbook (still in progress) for an undergraduate 3000-level Hispanic linguistics course, and we discuss the impact and power of the project on undergraduate student learning. This project illustrates how librarians, faculty, and students can collaborate in order to create OER that fill important needs and provide students with learning experiences that are more engaging and rewarding.

While OER are often touted as a means of making education more affordable, simply switching from a commercial textbook to an OER textbook does not necessarily ensure that the course will be delivered in a different manner. Saving students money is an admirable goal, but projects like the one we describe also improve teaching and learning by making them more innovative and learner-centered. This change in focus from open educational resources to open educational practices (OEP), is “concerned with opening up educational practices, for example, by shifting from teacher-directed to learner-centeredness, where learners can be more actively involved in the creation and use of resources for their learning” (Conole, 2013, p. 250). OEP transform students from mere recipients of content to active contributors to the greater body of knowledge. Ehlers (2011) defines OEP as “practices which support the (re)use and production of OER through institutional policies, promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning path” (p. 4). DeRosa and Jhangiani (2017) directly link OEP to the adoption of open pedagogy, which they describe as a process in which students take greater agency in their education by actively contributing to the public knowledge commons.

OEP recognize the importance of student production and peer-learning by emphasizing the creation and sharing of educational resources among students. This entails a shift away from “disposable assignments,” which Wiley (2013) describes as “assignments that add no value to the world – after a student spends three hours creating it, a teacher spends 30 minutes grading it, and then the student throws it away.” Instead of disposable assignments, students focus their energy on projects that will exist beyond the class, such as a textbook that will be used by other students in the future. Also, rather than focusing on predefined outcomes, OEP concentrate on the growth in the learning process itself. Conole (2013) explains that OEP aim for a learning environment in which “social processes, validation and reflection are at the heart of education, and learners become experts in judging, reflecting, innovating and navigating through domain knowledge” (p. 250).

Evidence shows that the high level of student engagement in OEP results in greater knowledge retention (Bonica et al., 2018). Additionally, by focusing on the creation of non-disposable assignments, this approach positions learning in a larger context than just that of the course at hand. Engagement in OEP through non-disposable assignments helps students forge a greater connection with the course content and take greater ownership of their learning by recognizing that it has a value outside of the classroom. As Bonica et al. (2018) explain:

The students understood that they were producing something that, if done well, could be used to show the quality of their work. This recognition triggered a high level of intrinsic motivation. They were no longer just working for a grade. Rather, they were working to create something that had clear value beyond the limits of the course. (p. 19)

By using OER as more than mere replacements for commercial textbooks, they can transform the teaching and learning process in ways that benefit students.

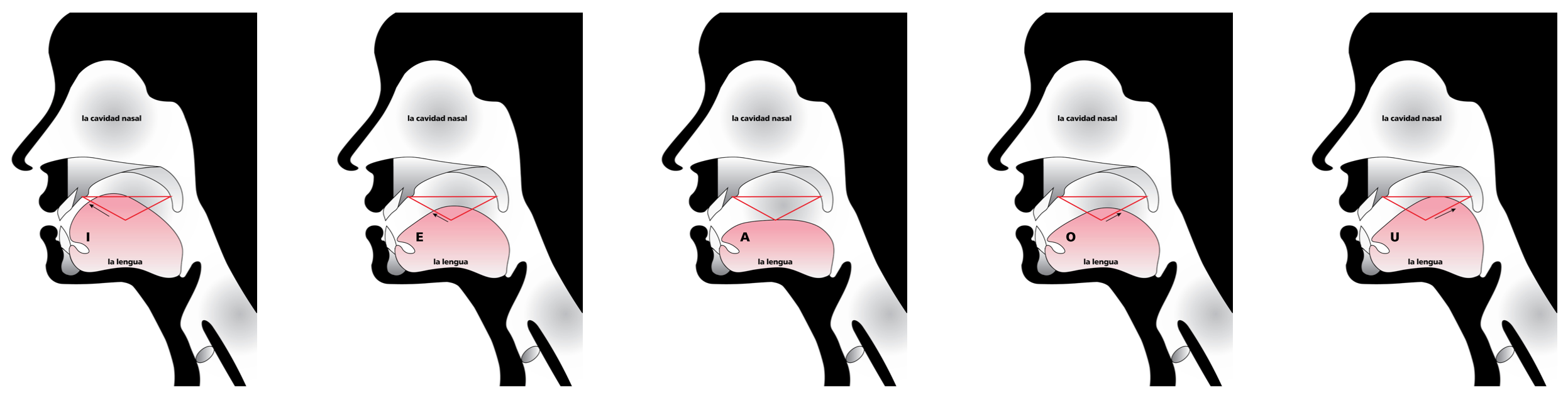

Although cost is often one of the principal motives that encourages the creation and use of OER, there are other legitimate and practical reasons that motivate a project such as this. In introductory Hispanic linguistics courses taught in Spanish, instructors face two unique challenges. The first challenge is that for many students, the Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics course is their first exposure to the discipline of linguistics, and the second challenge is that the linguistic concepts introduced to the students are presented in a language that they are still learning. The Linguistic Society of America notes that the term “linguist” is used in non-academic contexts to refer to language teachers (2020). Consequently, many students incorrectly assume that a linguistics course is an advanced grammar course. This makes them unprepared for common tasks in the discipline such as analyzing simple linguistic evidence, summarizing a scientific reading about aspects of language, and making a linguistic argument. The students’ ongoing endeavor of mastering a foreign language adds a higher level of challenge to these courses. It is very possible that in an Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics course, a student may be making their first attempt in Spanish at communicating scientific ideas using formal language. In many university Spanish programs students take Spanish language courses before taking a Spanish linguistics course. In Spanish language classes students learn to use Spanish in informal and formal settings. The advanced Spanish language courses are similar to English Composition courses: the emphasis is on learning to express opinions and thoughts through clear, coherent, cohesive, and engaging writing. It is only after taking language classes that focus on improving language and intercultural skills that students enroll in a Spanish linguistics course. Normally students have not used formal language in Spanish until this point to describe a scientific phenomenon or to write up an analysis using scientific terminology. In Spanish linguistics courses students learn to use linguistic terminology to talk about language and linguistic phenomena in a scientific way (e.g. how do humans make the sounds in their language, or in more technical terms, how does the interaction of the different organs of the human articulatory apparatus produce the phonetic inventory of a particular language?).

The commercial textbooks currently available for the introductory courses are written with the main purpose of transmitting large quantities of information, and frequently the language used in these textbooks is beyond the students’ proficiency level. These textbooks are used across diverse institutions (large research universities, liberal arts colleges, community colleges, and more), in different programs (Spanish majors with literature and linguistics courses, Spanish linguistics majors, Spanish literature majors with a minimal to no linguistics requirement) with little flexibility to adapt to their wide-ranging audience (heritage speakers, first-generation students, students from rural versus metropolitan areas, etc.). Publishers are unable to keep up with dynamic and constant changes – new linguistics research and current authentic examples of language on the internet – and incorporate them into the textbooks.

Ashwini Ganeshan, the professor leading the open-access Hispanic Linguistics Textbook (OAHLT) project, attempts to address these challenges. In order to create a more accessible and up-to-date Hispanic linguistics textbook, her goal with the OAHLT project is to publish a textbook that is composed solely of student-authored and student-edited texts on an open platform that can include many varied and changing sources of information and examples of language use. Because not all institutions offer a Spanish linguistics major and many institutions offer a Spanish minor or major with limited linguistics courses, the professor choses to include discussions of social justice issues into the textbook (e.g., the benefits and challenges of being bilingual or multilingual, the connection between accents and prejudice), making the topic of linguistics more relevant to the vast majority of students who do not plan on continuing to study linguistics and becoming researchers in the field. As of January 2020, the professor has published the first two chapters of the textbook, La lingüística hispánica: Una introducción, using the Pressbooks Open Book Creation Platform. The rest of the chapters are currently being compiled. A one-time PressBooks upgrade costing $99 was purchased since it allows the book to be downloadable in various formats (e.g. pdf, epub, mobi, xhtml), removes watermarks, and provides 250MB storage on the Pressbooks platform. The upgrade makes the book more discoverable and more usable for users, and the added storage is helpful for authors and editors to store a variety of files directly on the platform.

Before delving into the process through which the textbook is being created, for clarity and ease of reading, the authors identify the different people that are involved in the creation of this textbook. They are the professor leading the project (Ashwini Ganeshan, pronouns: she/her), the students enrolled in the professor’s Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics courses, the student-editors hired to edit the texts, and the librarians (Bryan McGeary, department liaison librarian for Modern Languages, pronouns: he/him; and Chris Guder, subject librarian for Education, pronouns: he/him) who supported the project in various ways. Additionally, an art student was hired to draw illustrations in the textbook and an alumna and current staff member of the university designed the cover of the textbook (See illustrations and cover image in Appendix A). We refer to these main roles (the professor, the students, the student-editors, the librarians) and elaborate on them in the rest of the description of the OAHLT project.

The idea for the project originated during the academic year 2016-2017. In the fall the professor taught an Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics course. She observed that her students could explain complex linguistics concepts in simpler and well-written texts that were more accessible to their peers. She initially considered reusing her students’ work, with their permission, in future classes as readings to accompany the text. In the spring the professor attended a series of workshops on OER, information literacy, and Creative Commons licenses led by the Ohio University librarians and decided instead to create a textbook using those texts, resulting in the OAHLT project. That same semester, the professor also participated in the Reimagining the Research Assignment workshop (Saines et al., 2019), in which faculty worked with their subject liaisons to revamp their research assignments to incorporate information literacy standards better. In this workshop, she worked closely with her departmental liaison librarian to create the study guide final project for the course she taught that semester. The study guide project was the first way in which the professor attempted to gather texts for the OAHLT project.

For the study guide project students in the professor’s Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics course worked in groups to create a study guide for their chosen field of Hispanic linguistics (e.g. phonology, morphology, syntax). Through this project, students provided basic content, such as key concepts and their definitions as well as simple exercises, for these different fields. The professor informed students of the study guide project a little more than a month before the last day of classes. After giving students instructions about the study guide project and how it would be graded, the professor also announced that these study guides could be utilized for the OAHLT project if students wished to provide their consent. In order to obtain consent in an ethical manner, the professor requested the help of a staff member in her department. At the end of the semester the staff member handed out the consent forms to students and then collected and placed them in a sealed envelope. Once the professor submitted the final grades, the staff member verified the submission and handed over the sealed envelope. This procedure ensured that there was no undue coercion to contribute materials to the project. The professor has continued to use this consent procedure with all other student groups that have since then worked on materials for the textbook.

Once the students started working on the study guides in groups, the professor arranged for the departmental liaison librarian to provide the students with a workshop on Creative Commons licenses. She explained to the students that since this textbook was meant to be created through student-authored texts, they could decide what Creative Commons license to use for the textbook. After the workshop the students were given a week to discuss the matter among themselves before deciding together in class. The students decided as a class to license the textbook under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC-BY-NC-SA) because they were enthusiastic about making the book available for free to their peers and wanted to ensure that no one could profit financially from their collaborative work.

After final grades were submitted at the end of the semester, the professor received the consent forms in the sealed envelope from the staff member and was pleasantly surprised that all students had provided their consent. Encouraged by this result, the professor started to design different assignments for her Introduction to Hispanic Linguistics course that could complement the material already collected and provide more substantial main texts and exercises for the new textbook (for examples see Appendix B). In all her following courses, students completed these assignments as part of the routine coursework, and the resulting texts are now utilized as the main texts and exercises for the new textbook. For most of the assignments students were required to revise, edit, and re-submit their work after a round of feedback from the professor, ensuring student learning and a quality end product. The individual homework assignments included short answers, essay questions, and exercises with answer keys, each filling out different parts of the textbook. A sample of each of these is provided in Appendix B with a link to the outcome in the open access textbook. The study guide assignment, other assignments, and the syllabus for the course can be accessed on the professor’s website.

The professor continues to gather materials from her students through the methods described above. The contributed materials include texts explaining important linguistic concepts, essays on pertinent issues in Hispanic linguistics, and exercises in linguistics. At the end of every semester students are introduced to the project and are invited to contribute the materials they have already created as part of the course work to the textbook. Students are informed that if their material is used, they will be listed as contributors in the textbook. Students’ consent is obtained through the signed consent forms procedure described previously.

The first group of students that worked on the study guide project differ from the following groups of students: the first group knew that their work would contribute to the OAHLT project while working on the study guides, whereas the following groups of students were only told at the end of the semester after their work was completed. The professor hesitated to inform any students about the project early on because there was no end-product in the form of chapters that she was able to show them. However, she did discuss with them that the assignments submitted needed to use formal language and simple explanations that were accessible to their peers. Now, with two chapters of the textbook published the professor can show future students what their work contributes to, fully aligning with the principles of OEP. The professor is optimistic that when students can envision their work in the textbook and realize that they will be creating a lasting and meaningful text, it will motivate them to engage in deeper learning.

In order to keep the textbook student-authored the professor applied for grants available through her university to hire students with knowledge of Spanish and linguistics as student-editors for the book. Through the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship grant, the Program to Aid Career Exploration grant, and the 1804 grant, the professor advertised the student-editor position. Selected applicants went through an interview process that inquired about their interest and motivation to be a student-editor and tested their Spanish skills and linguistics knowledge. The professor hired four student-editors for the project. Each editor held a three- to nine-month term as student-editor and did not overlap. The student-editors helped edit, organize, and format the student-authored texts under the professor’s supervision. They discussed and finalized chapter outlines with the professor and helped plan the content of the textbook. They also researched and incorporated current and open online resources into the textbook, including images, audio, videos, and blogs, to keep the textbook up to date. They learned to work with the Pressbooks platform and set up the texts on Pressbooks, working on all the final formatting of the texts. All this work has resulted in the publication of the first and second chapters of the textbook, La lingüística hispánica: Una introducción, on the Ohio University Institutional Repository. The professor and the current student-editor are working on compiling and completing the rest of the chapters. In order to provide a different way for students to access the book, the current student-editor is also audio recording the first two chapters of the textbook.

Although the process – assignments, revisions, final product – seems linear, it was not. In some instances, after compiling work submitted by students, the professor and student-editors realized that there were still gaps in content to fill. Sometimes the professor went back to the students in the classroom the next semester and collected materials to fill the gaps through assignments; other times, the student-editors filled the gap themselves by contributing original material. For example, students were assigned a question on the homework that asked them the difference between linguistic competence and communicative competence. The answer students provided was generally a basic text to explain the difference between the two important linguistics concepts. In a different homework assignment, students were asked to explain why students of Spanish are often able to explain grammar rules but still make mistakes when speaking using the same concepts of competence. The best answers provided by students were compiled by one student-editor into a longer cohesive and coherent text. Another student-editor added to this text a different point of view, that of linguistic and communicative competence of Hispanic immigrants and their children who are differently proficient in English and Spanish. This final text thus connects the topic of linguistic competence and communicative competence to other social-justice issues, such as the stigma against bilingualism/multilingualism (incorporated as a topic in the textbook) and the social-burden these children carry as translators for their parents in U.S. society (link provided in the textbook to an article that discusses the issue). This nonlinear process, in our opinion, enriches the teaching and learning experience and has resulted in a more complex and interesting textbook.

Throughout this project the professor’s departmental liaison librarian provided information on open textbooks, information literacy, and Creative Commons licenses to the professor and the student-editors. He also provided letters of support when the professor applied for grants to hire student-editors for the project. The departmental liaison librarian initiated and led a collaboration with the professor and the subject librarian for Education to apply for a university grant to support the creation of OER and open pedagogy projects. The professor received additional monetary support through this grant to hire student-editors. The professor and the librarians continue to have a strong team dynamic and work together in a flexible manner to respect and accommodate each other’s knowledge, competencies, and schedules. For example, the librarians acknowledge that the professor can only work on the project when she has the opportunity to teach the linguistics class and sometimes at a slower pace, given her other responsibilities on the tenure track, and the professor keeps the librarians informed of the progress made every semester.

From a pedagogical perspective by engaging in this project, students and student-editors not only improve their language skills and knowledge of linguistics concepts, they also create a textbook effective for students and share their knowledge with their peers. Rather than passively receiving information from a static textbook, students are engaging with a body of knowledge to which they are actively contributing (DeRosa & Robison, 2017). The OAHLT project engages students in renewable assignments which, as Wiley (2015) states, “result in meaningful, valuable artifacts that enable future meaningful, valuable work”. From the professor, the student-editor learns important professional transferable skills such as the rules of writing and formatting in the field of linguistics as well as how to edit academic texts, including checking facts, data, citations, and footnotes. From the librarian, the student-editor learns about copyright, plagiarism, Creative Commons licenses, and open access publishing platforms and repositories.

Open pedagogy allows students to engage in higher-order thinking tasks from Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy, such as analyzing, evaluating, and creating. Open pedagogy also provides students the opportunity to take part in significant learning experiences, especially in terms of how to learn, integration of knowledge, caring, and the human dimension as described in Fink’s (2013) “Taxonomy of Significant Learning.” This project involves students in the application and integration of foundational knowledge, when they create materials for the textbook and when student-editors evaluate and edit these texts for the final product. Both students and student-editors learn that their work has value and that they can be effective carriers, contributors, and transmitters of knowledge. Through this project they are engaging in inquiry and are constructing knowledge in the field of Hispanic linguistics. This project allows students and student-editors to show creativity when exemplifying linguistic concepts or terminology, and when they come up with practical solutions to content and logistical matters, ensuring the book is better understood by future readers, their peers. Overall, this project creates a more effective, engaging, and lasting learning experience for students.

The OAHLT project we have described in this chapter embodies several facets of OER-enabled pedagogy (Wiley & Hilton, 2018). Wiley and Hilton identify a distinction between what is often referred to as open pedagogy and to what they define as OER-enabled pedagogy. In their pedagogical model, the output must enable the creators to make decisions about copyright licenses and permissions attached to their work. To this end, Wiley and Hilton (2018) have developed a simple four-part test that can be used to evaluate projects to determine the extent to which their definition of OER-enabled pedagogy is being implemented:

- Are students asked to create new artifacts (essays, poems, videos, songs, etc.) or revise/remix existing OER?

- Does the new artifact have value beyond supporting the learning of its author?

- Are students invited to publicly share their new artifacts or revised/remixed OER?

- Are students invited to openly license their new artifacts or revised/remixed OER? (p. 137)

Apart from incorporating the facets of OER-enabled pedagogy, the project makes the copyright licenses and permissions a condition and prerequisite to the content creation. Through the OAHLT textbook project the professor combines several benefits related to open pedagogy and invites the students to understand and contribute to the global conversation by making their work be available freely on the internet.

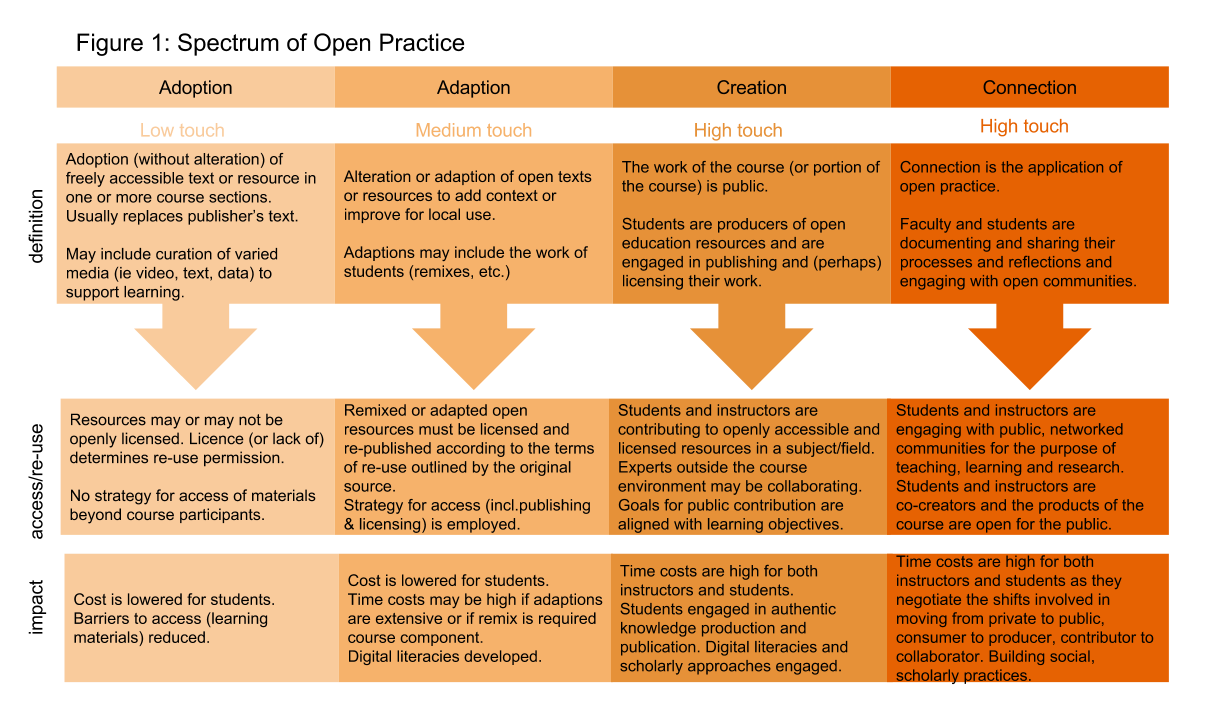

While creating an open textbook using student-authored texts improves the teaching and learning experience in the many ways outlined above, it is also a challenging endeavor. Creation is at the higher end of the spectrum of open practice (Figure 1) and requires a greater investment of time. Based on the way this project is designed, the main challenge of time or lack thereof affects only the faculty member and not necessarily the students. Although students are also under pressure to submit assignments on time, students’ time invested is expected as part of the course work, and for student-editors, their time is paid. Not many faculty members have the time to dedicate to a long-term project like this, especially if it is not recognized and valued sufficiently nor substantially in their institutions.

Figure 1

Spectrum of Open Practice

In general, as Roberts (2018) states, there exists an “enormous barrier presented by systemic policies and the tenure and promotion process” that discourages faculty from participating in open education. At Ohio University, as with many institutions, OER creation does not have a significant impact, if any, when it comes to securing tenure, because it is seen as a teaching-focused activity rather than something that fulfills research requirements. As James Skidmore, associate professor and director for the Centre for German Studies at Waterloo University, explains, “For some people, it’s a question of how much time they want to put in their teaching. So typically at a research institution, faculty are told to not overdo it on the teaching. [The notion is] do enough to be good, but don’t do more than that” (Roberts, 2018). This advice can be particularly problematic for a faculty member who is currently on the tenure track.

In hindsight, the professor recognizes that some changes could have been made in terms of the process for the creation of the textbook. More time could have been dedicated to plan the project before beginning the work of collecting texts so that texts could be collected in such a way that they are ready to be incorporated into the textbook without editing. The professor also acknowledged that she could have fully embraced the practice of OEP by telling students upfront what their work was contributing to. In addition, the professor could have presented the students with a skeleton of the textbook and asked them to directly fill in sections to complete the book. The majority of the student texts in this project were of good quality, devoid of serious language and content errors, given the process of students revising and correcting their own work. However, the texts were not necessarily ready to be cut and pasted into the textbook in their current form. As described above, the student-editors also worked on the texts resulting in a more complicated and lengthy process. Another suggestion would be to investigate possible partnerships with faculty teaching the same course so the project could move faster, even though it cannot be assumed that collaborations may take less time. Any expectation for a project of this size and complexity to move in a linear and smooth manner is also unrealistic. Additionally, often faculty members do not have control over what courses they are assigned, and this can delay the process as well. The professor therefore recommends taking it slow and enjoying the process instead of focusing on the resulting product, since the process itself aids in professional and personal growth.

In terms of adaptability of this project, the creation of exercises and answer keys is the most easily adaptable part of this project, followed by the explanation of concepts with examples that students are familiar with/relate to (See examples in Appendix B). Since each of the chapters of this textbook is unique in organization, the project cannot be replicated exactly or expanded on in the same way as other inspirational projects such as the Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature or the Antología Abierta de Literatura Hispana. In broad terms, the model described here of creating an open textbook within a course and the use of partnerships between faculty, librarians, and students is something that can be replicated by faculty at other institutions.

While the professor and her students have been the catalyst and authors of this project, the partnership between the professor and the librarians has proven to be beneficial to both. Through workshops and other library events the professor was able to learn more about open access and engage with others on campus who have similar interests in OER and open pedagogy. Having access to a unit on campus that has expertise in publishing, scholarly writing, open access, and copyright proved to be beneficial not only to the professor and students as authors, but also to the Libraries’ significance in the area of OER and how well the Libraries are situated to partner on other OER projects.

At Ohio University there are now two additional local projects: one that has a student creating a test bank for an art history survey course, and another that involves a faculty member creating their own open textbook out of course materials and open access government documents. These types of partnerships are proving beneficial to the Libraries by increasing library engagement with academic departments, demonstrating the tangible impact that they make on student success, and enabling them to take a leadership role on campus in the area of OER. As interest in OER expands, the Libraries are positioned to provide new services to support those needs. Currently, the Libraries are piloting some services aimed at addressing those needs. These initiatives include the provision of financial support to hire students to assist faculty with OER creation and to purchase any necessary publishing tools, such as a Pressbooks upgrade.

The leveraging of partnerships between faculty, librarians, and students that we describe can be replicated by faculty, librarians, and students at other institutions to create similar projects of their own that harness the power of student-created content. Since monetary costs have been relatively modest, the largest expense has been the time of all those involved. However, the benefits outweigh the challenges, and as the value of open pedagogy becomes more apparent to students, faculty, and libraries (not to mention universities and legislators), the case for dedicating resources and librarian time to collaborate with faculty and students on such projects should become stronger. Projects of this nature provide a richer, more engaging learning experience for students as they become knowledge producers rather than just consumers.

References

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. McKay, 20-24.

Bonica, M. J., Judge, R., Bernard, C., & Murphy, S. (2018). Open pedagogy benefits to competency development: From sage on the stage to guy in the audience. The Journal of Health Administration Education, 35(1), 9–27. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/aupha/jhae/2018/00000035/00000001/art00003?crawler=true

Conole, G. (2013). Designing for Learning in an Open World. Springer New York.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8517-0

DeRosa, R., & Jhangiani, R. (2017). Open pedagogy. In E. Mays (Ed.), A guide to making open textbooks with students (pp. 7-20). The Rebus Community for Open Textbook Creation. https://press.rebus.community/makingopentextbookswithstudents

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2017). From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. In R. S. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolutionizing education and science (pp. 115–124). Ubiquity Press.

https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

Ehlers. U-D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open

educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1-10.

http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/view/64

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to

designing college courses. Jossey-Bass.

https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

Linguistic Society of America. (2020). The science of linguistics.

https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/science-linguistics

Roberts, J. (2018, May 16). Where are all the faculty in the open education movement? EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2018-05-16-where-are-all-the-faculty-in-the-open-education-movement

Saines, S., Harrington, S., Boeninger, C., Campbell, P., Canter, J., & McGeary, B. J. (2019). Reimagining the research assignment: Faculty-librarian collaborations that increase student learning. College & Research Libraries News, 80(1), 14-17, 41.

https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.80.1.14

Underhill, C. (2017). Spectrum of Open Practice [Online image]. University of British Columbia Wiki. https://wiki.ubc.ca/File:Spectrum_of_Open_Practice_-_Working_Draft.png

Wiley, D. (2013, October 21). What is open pedagogy? [Blog post].

https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975

Wiley, D. (2015, August 3). An obstacle to the ubiquitous adoption of OER in US higher education [Blog post]. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/3941

Wiley, D. & Hilton, J. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Contact Information

Author Bryan James McGeary may be contacted at bjm6168@psu.edu. Author Ashwini Ganeshan may be contacted at ganeshan@ohio.edu. Author Christopher S. Guder may be contacted at guder@ohio.edu.

Feedback, suggestions, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

Author’s Note

My deepest thanks to my enterprising students who contributed to this OAHLT project, to the student editors—Maggie Saine, Paige Wilson, Anna Traini, Analee Davis, Elle Dickerman—for their labor and creativity, and to many, many other people who supported this endeavor in enriching ways.

—Ashwini Ganeshan

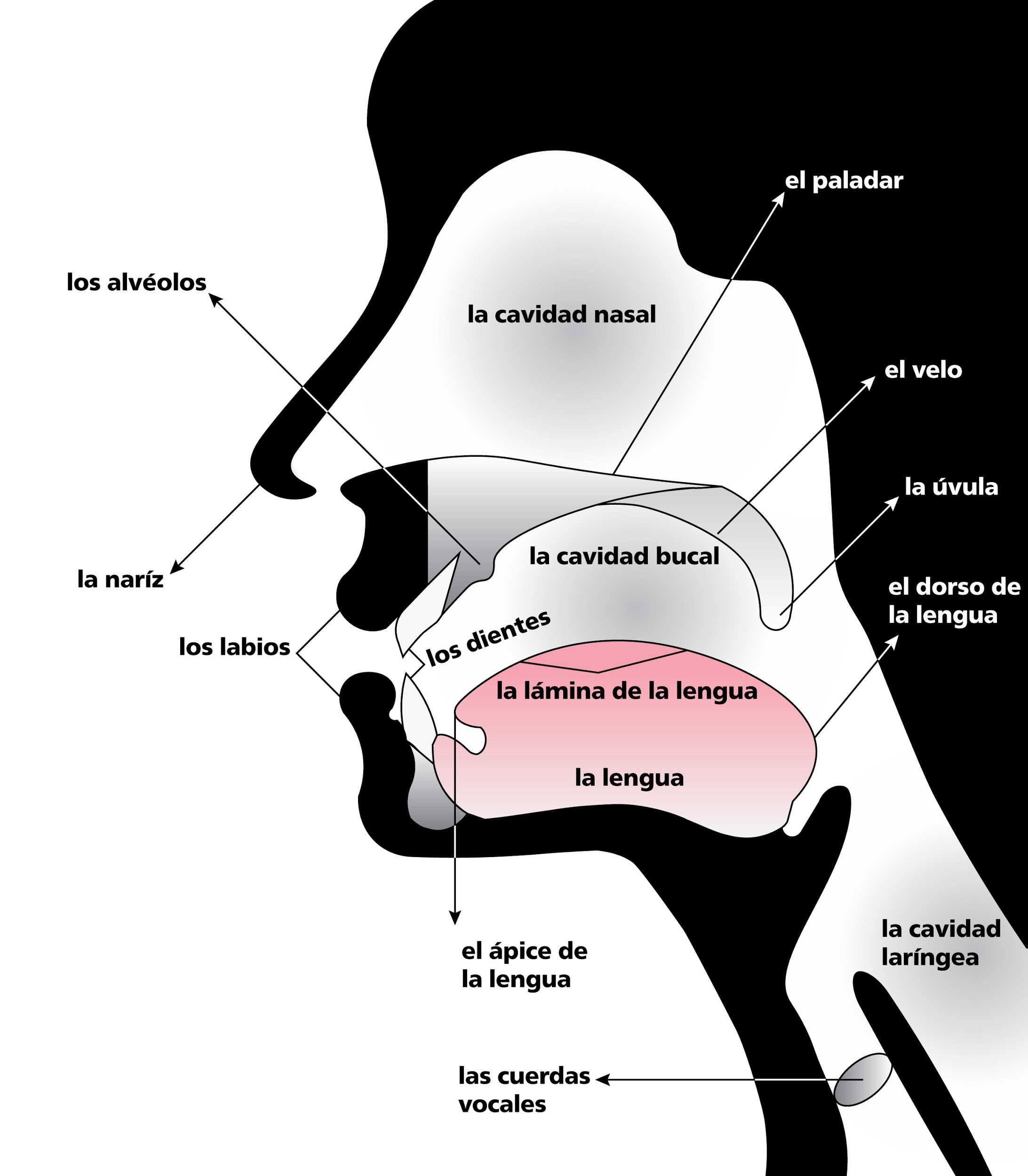

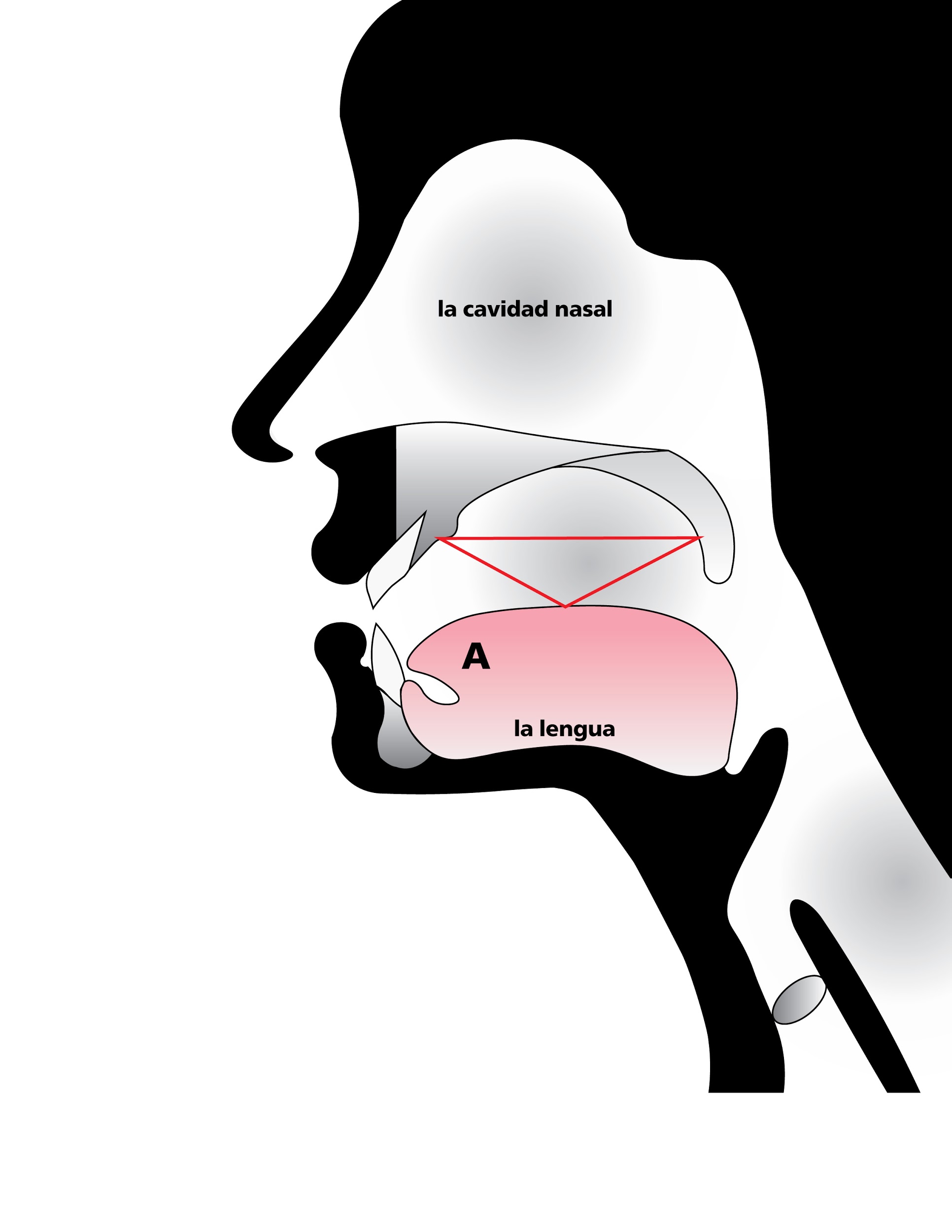

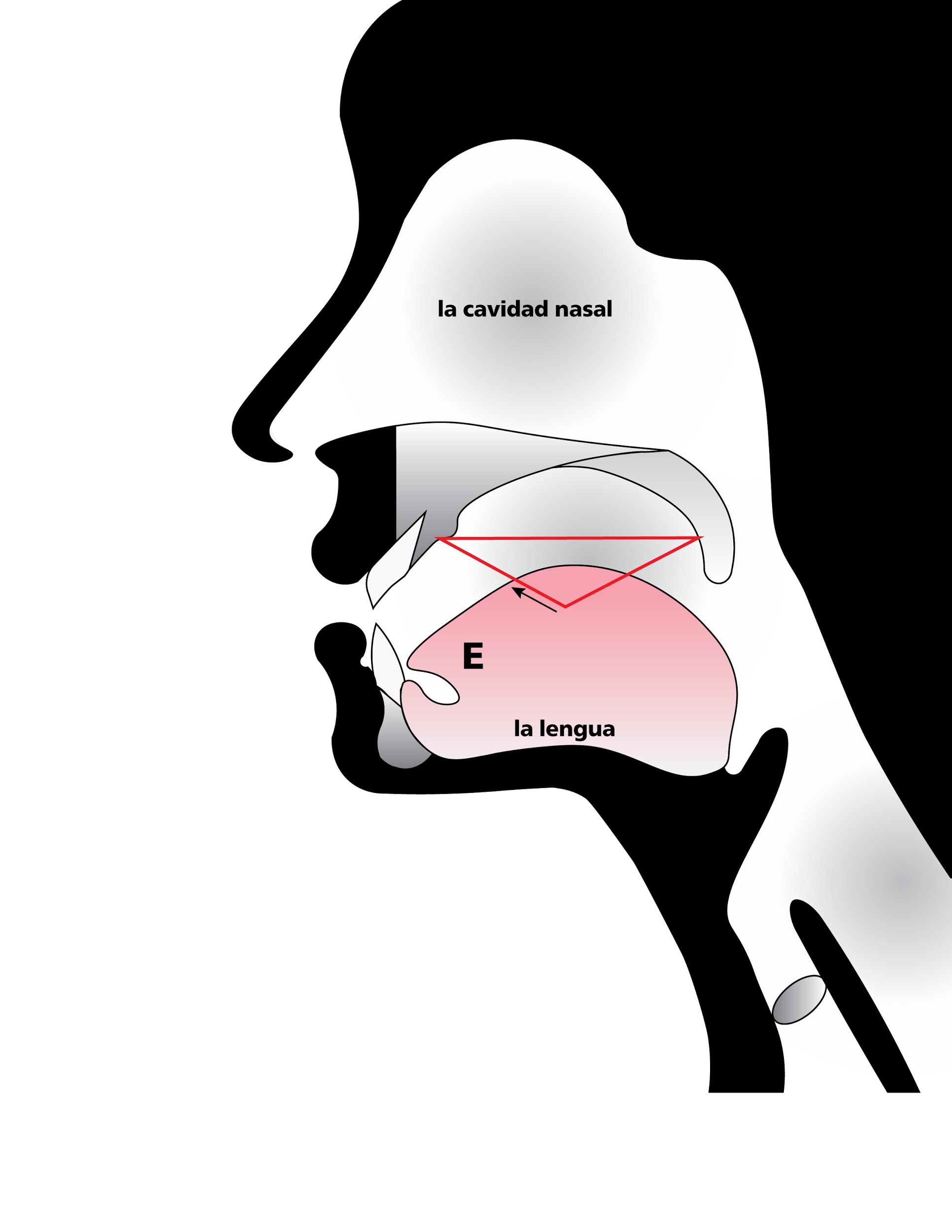

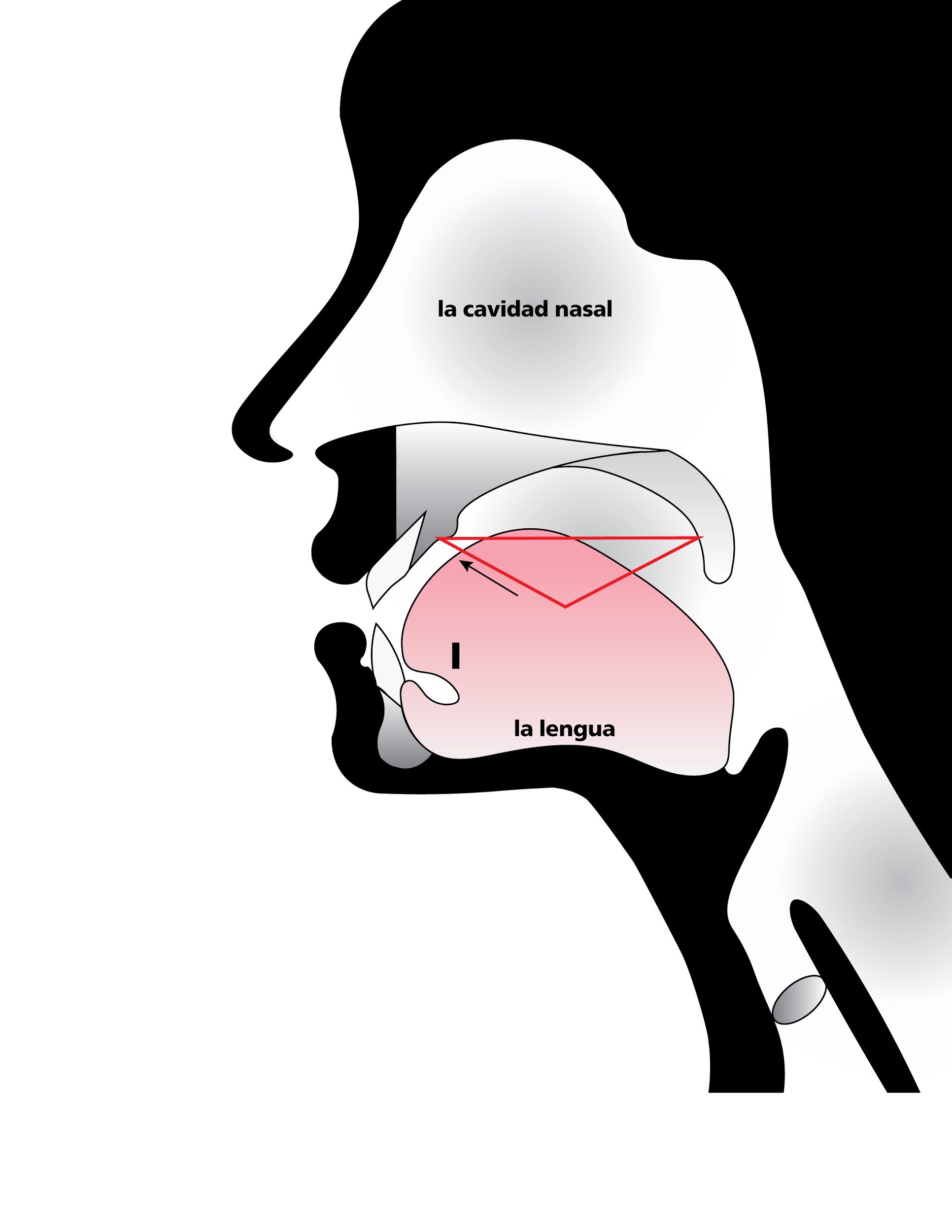

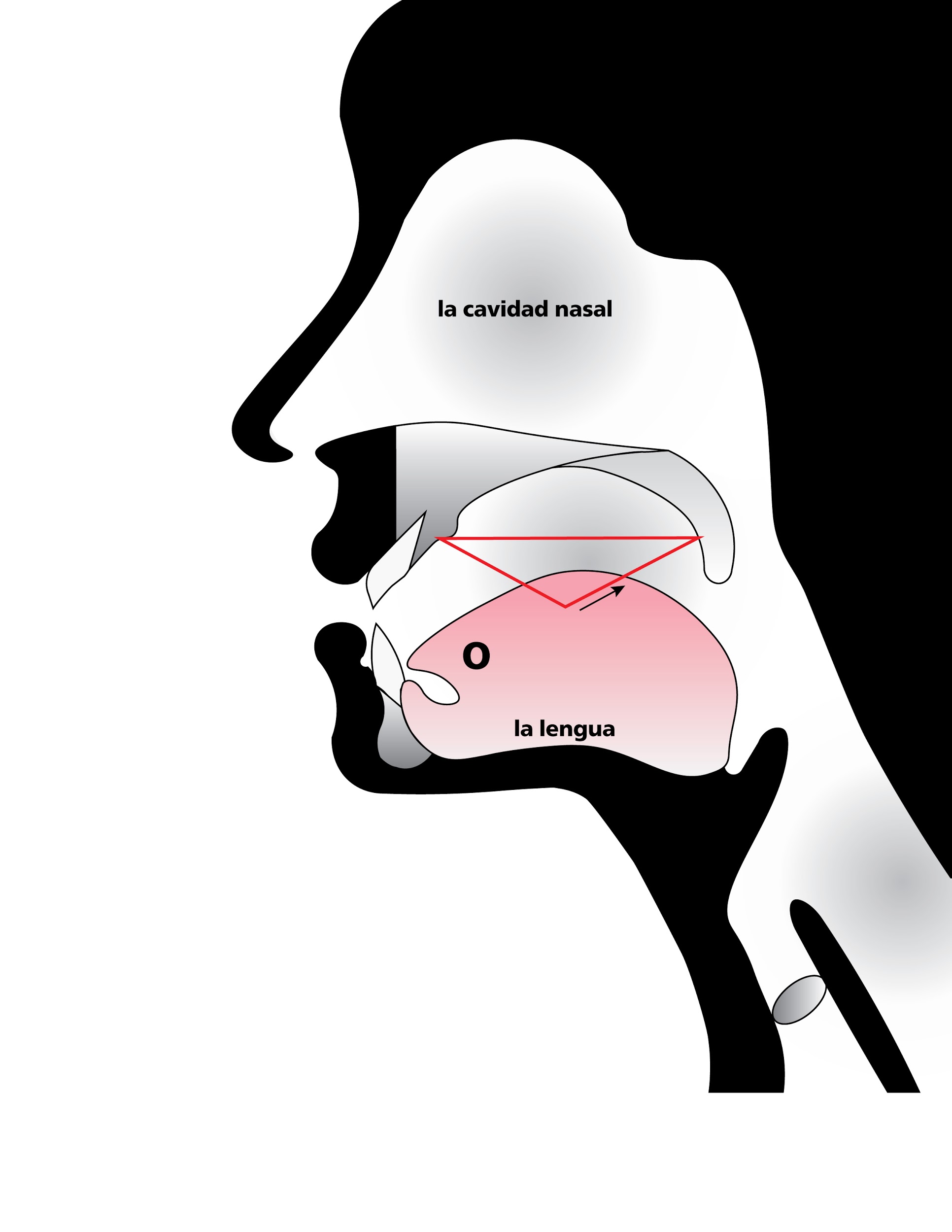

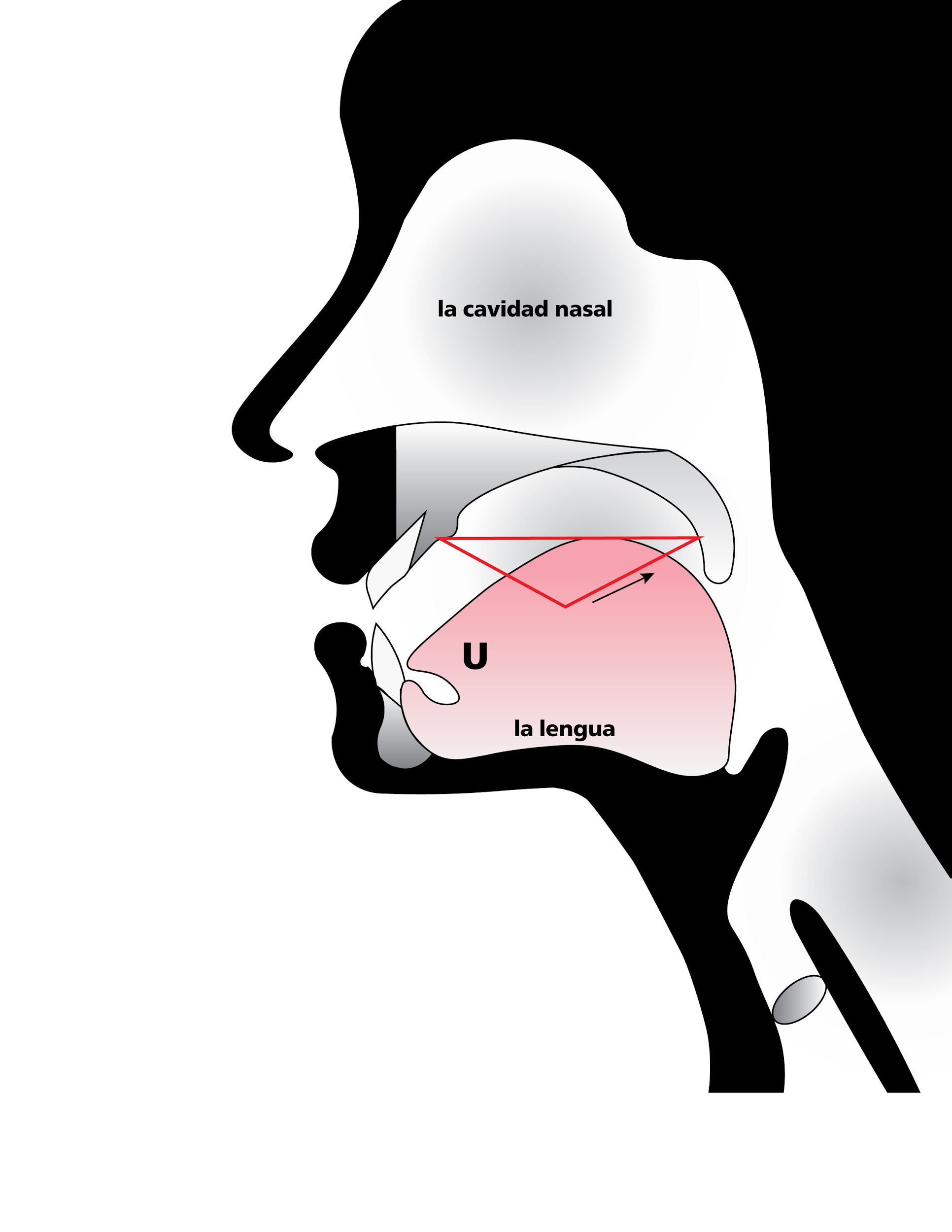

Appendix A: Illustrations and cover image

Illustrations made by Emily Dialbert:

- Link 1: Phonetic Apparatus

- Link 2: Vowels

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Appendix B: Examples of assignments

The example assignments presented here provided content for Chapter 1 of the textbook. All the assignments are written in Spanish and have been translated into English here for convenience.

We have linked each question to the part of the book they resulted in after editing by the student-editors.

Short answer questions

- Explain the difference between:

- Give two examples each of prescriptive rules and descriptive rules of a language that you speak.

Essay question

Exercise with answer key

- Create a practice exercise with answer key for one of the following topics:

Appendix C: Image Description

Figure 1 Long Description

Figure 1: Spectrum of Open Practice

Adoption (low touch)

- Definition: Adoption (without alteration) of freely accessible text or resource in one or more course sections. Usually replaces publisher’s text. May include curation of varied media (i.e. video, text, data) to support learning.

- Access/Re-use: Resources may or may not be openly licensed. License (or lack of) determines re-use permission. No strategy for access of materials beyond course participants.

- Impact: Cost is lowered for students. Barriers to access (learning materials) reduced.

Adaption (medium touch)

- Definition: Alteration or adaption of open texts or resources to add context or improve for local use. Adaptions may include the work of students (remixes, etc.).

- Access/Re-use: Remixed or adapted open resources must be licensed and re-published according to the terms of re-use outlined by the original source. Strategy for access (incl. publishing & licensing) is employed.

- Impact: Cost is lowered for students. Time costs may be high if adaptations are extensive or if remix is required course component. Digital literacies developed.

Creation (high touch)

- Definition: The work of the course (or portion of the course) is public. Students are producers of open education resources and are engaged in publishing and (perhaps) licensing their work.

- Access/Re-use: Students and instructors are contributing to openly accessible and licensed resources in a subject/field. Experts outside the course environment may be collaborating. Goals for public contribution are aligned with learning objectives.

- Impact: Time costs are high for both instructors and students. Students engaged in authentic knowledge production and publication. Digital literacies and scholarly approaches engaged.

Connection (high touch)

- Definition: Connection is the application of open practice. Faculty and students are documenting and sharing their processes and reflections and engaging with open communities.

- Access/Re-use: Students and instructors are engaging with public, networked communities for the purpose of teaching, learning and research. Students and instructors are co-creators and the products of the course are open for the public.

- Time costs are high for both instructors and students as they negotiate the shifts involved in moving from private to public, consumer to producer, contributor to collaborator. Building social, scholarly practices.

Chatting with friends about likes and dislikes, ordering food at a restaurant, narrating stories to friends and family.

Talking to your professor or boss at work, taking a stand on an issue - climate change, refugees, free education - and arguing for or against it especially in essay or presentation form.

The intuitive knowledge that a speaker has about a language they speak.

The ability to use a language appropriately in real-time communication.