Open Pedagogy as Open Student Projects

Building a Collection of Openly Licensed Student-Developed Videos

Ashley Shea

Author

- Ashley Shea, Cornell University

Project Overview

Institution: Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Institution Type: public, statutory, land-grant, undergraduate, postgraduate

Project Discipline: Agriculture

Project Outcome: student-produced videos

Tools Used: LibGuides, iMovie, OpenShot, Institutional Repository

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Resource Guide

- Assignment Rubric

- Teaching Materials

- Sample Release Form

Introduction

Proponents of open access have long argued that scholarly output should be obtainable without technical and economic barriers (Willinsky, 2006). Although laudable, focusing on access alone in the context of student learning is insufficient. When so much of one’s understanding depends on interactions with the content, the conversation on “openness” must also include the processes and tools capable of content creation and sense-making (Knox, 2013b, 2013a). In this chapter, I introduce an assignment from an undergraduate agriculture class that undermines the argument for mere content access. Now running in its fifth year, this student video project has evolved beyond basic instruction, which first accompanied the assignment, to include complex pedagogical design and thoughtfully designed learning outcomes. In the first year, the assignment included directions for finding open access content—such as music, photos, and film footage—to integrate into videos. However, it now includes accompanying instruction on the tools and processes capable of creating, modifying, and distributing such content, including open pedagogical practices, open source tools, and open licenses. Similar to the field of agriculture where access is sought to the biotechnology tools and research methods that produce proprietary seeds (Adenle et al., 2012), the field of education is reckoning with the inherent value of the processes and tools underlying final educational output.

PLSCS 1900

Soil and Crop Sciences (PLSCS) 1900: Introduction to Sustainable Agriculture is a medium-sized survey course taught at Cornell University each fall. Cornell University serves as New York State’s land-grant university and is comprised of four statutory colleges and four private colleges. The land-grant mission of the university applies to the statutory colleges and includes a commitment to translate applied research into practical knowledge for direct application by residents of the state, nation, and the world. PLSCS 1900 is nestled within one of Cornell’s statutory colleges, the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The video assignment for PLSCS 1900 is a deliberate effort to encourage students to share the knowledge that they develop in class with a wider audience for larger public impact.

Roughly 70 students enroll in PLSCS 1900 annually. The class meets twice weekly for 50-minute lectures and once weekly for a three-hour lab. During lecture, students learn about different topics in sustainable agriculture—such as cover crops, dairy farm management, and integrative pest management—while during lab, the class travels to nearby farms to further examine topics from lecture. For years, the final assignment in the class was a standard research paper that yielded little enthusiasm from students and required significant grading time by the professor and teaching assistant. Several years ago, when a new professor inherited the course, the research paper was replaced with a video assignment. Each student was asked to independently create a short video about any aspect of sustainable agriculture and present their video to the class at the end of the semester. As the liaison librarian to the department in which the class is housed, I was asked to support the assignment during the first year of the video assignment by creating and then introducing a resource guide (Appendix A) in a 20-minute “one-shot” guest lecture. My resource guide provided directions on finding open access images, music, and video footage that students could utilize in their videos and highlighted the videography equipment available for circulation at the library. At the end of the semester, I was invited to the final lab periods where students presented their films.

Addressing Pitfalls of Initial Video Assignment

In the first iteration of the project, students were left to independently learn how to synthesize a body of evidence and integrate resources to present a clear argument in video form. As the due date approached, students scrambled to produce a tangible product and many uploaded exceedingly large files. The final videos were of low quality with few articulating and supporting a clear message. After viewing the student films that first year and being disappointed in the quality, the professor and I brainstormed ways to revise the assignment so the output would improve.

As a new professor, he was incredibly open to my ideas and involvement in the class. As it happens, I had taken the same class as an undergraduate at Cornell from his predecessor and possessed knowledge about the course that he and the students could benefit from. And as a new librarian that was entering the field at the time that the Association of College and Research Library’s new Framework for Information Literacy was introduced, I was eager to lean into the new Framework to justify extensive librarian involvement in the assignment. With frames that included “Authority is Constructed and Contextual,” “Information Creation as a Process” and “Information has Value,” the new framework underscored the librarian’s role in the student learning process. It positioned librarians to help students recognize the value in seeking various information types, making sense of that information and then synthesizing it in new forms for use by others (Stripling, 2010). I interpreted the Framework broadly to include both digital and analog content and skills, and believed the nature of the video assignment aligned well with my interpretation. I asked the professor if I could provide training to the students on the use of videography equipment and editing software, as well as basic instruction on storyboarding practices and general copyright education in future iterations of the class. I lacked all of these competencies at the time, but felt strongly that they would contribute to my digital literacy and pedagogy skills and enhance the depth of my knowledge when providing instruction on any information literacy topic in the future. The professor agreed, and strongly encouraged my contributions. Indeed, he supported me largely taking the lead on the project.

Over the course of the summer that preceded the next class, I developed my skills and built a solid infrastructure for the project. I first met with a team of web developers that maintain eCommons, Cornell’s institutional repository that provides open access to the research and educational output from the university. With their help, we developed a process that streamlined the video submission process for students while simultaneously allowing for self-deposit in the repository so their videos could be used as teaching examples in future years. I then met with the library’s Director of Copyright Services to learn more about copyright and Creative Commons license options and concerns related to the Family Education Rights and Protection Act (FERPA). She designed a consent form that students would sign if they agreed to archive their work in eCommons.This consent included the agreement to affix a CC-BY-NC license to each student’s film. Falling somewhere in the middle of “most restrictive” and “most open,” this license seemed like a happy medium for graded student work and was in alignment with the rules established in the university’s code of academic integrity.

After meeting with the Director of Copyright Services, I then worked with the library’s Instructional Technology Coordinator, who has significant experience in video capture and editing. He provided me with a brief tutorial on the functionality available in iMovie. I then supplemented this self-guided professional development with online tutorials and videos from Lynda.com on things like video production and storyboarding. Pulling this all together, the professor and I collaborated to rewrite the original assignment and associated instruction for it. We transformed a last-minute replacement in the syllabus to a structured, pedagogically sound assignment that utilized Open Education Practices (OEPs). The result has led to frequently viewed and openly licensed videos created by budding undergraduate videographers who just happen to be studying agriculture.

Grounding an Assignment Redesign in Pedagogical Principles

Open Educational Practices (OEPs) seek to recognize the agency that students have when developing competencies and skills (Ehlers, 2011) and embrace ‘pedagogical openness,’ such as active learning, interactive and adaptable learning tools, and peer collaboration (Murphy, 2013). Active learning refers to the pedagogical approach of incorporating hands-on engagement when constructing knowledge to promote creativity, critical thinking and knowledge transfer across disciplines (Armbruster et al., 2009; Burbach et al., 2004; Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2004). Indeed, when an instructor’s teaching philosophy aligns with constructivism, or the belief that knowledge is constructed and developed over time at each student’s pace, the classroom becomes student-centered, learning is kinetic and students report higher levels of engagement with the course material (Dori & Belcher, 2005; Sawers et al., 2016). Active learning prevents students from passively consuming information and requires involvement in the production of new knowledge and understandings (Bransford et al., 2000; Knight & Wood, 2005). All of this, of course, is key when tasking students with creating a short video. This would otherwise be a daunting assignment for most undergraduates in the life sciences who have never done this before.

Generating student engagement is notoriously difficult to build in one class session but easier when integrated into the course (Kvenild & Calkins, 2014; Mery et al., 2012; Walker & Pearce, 2014). As such, the professor agreed to let me implement a problem-based learning instructional framework for the assignment that would span several weeks, thus exposing me to students multiple times to facilitate hands-on collaboration, creativity and critical thinking (Kenney, 2008). Problem-based learning incorporates realistic tasks into the instructional framework to encourage future recall and application of information. It also underscores the idea that education is most effective in the context of future anticipated scenarios (Glaser, 1982). With this in mind, I introduced new, solvable problems that would be included throughout the semester that focused on the skills required for successful completion of the assignment.

Nuts and Bolts of the Revised Assignment

The first step when re-writing the assignment was to clarify desired learning outcomes. When the project was conceived, the professor desired to promote creativity while encouraging the development of technical skills. Somewhere throughout the first year of the project, the professor and I also recognized the need to educate students about their rights and responsibilities when creating and using content. Altogether, these goals were commendable, but they lacked specificity and an assessment plan. Without clear parameters and definitions, students floundered.

With my willingness to take the lead on the redesign and execution of the project, the professor formalized my role in the class by listing me as a co-instructor on the syllabus, further codifying my ability to contribute. Relatedly, he shared confidence in my vision, provided instructor-level access to the course Learning Management System, and encouraged my involvement in the assignment grading process, even with other assignments and course lectures. By acknowledging my role, he empowered me with creative and intellectual freedom to develop a high quality, high-impact student assignment.

When introducing the assignment in the second year, in the interest of employing OEPs from the beginning, we encouraged students to work together in groups of 2-3 and we outlined expectations of group members. To avoid unwieldy and epic films, we also established time limits on the videos and asked that they be between 3 to 5 minutes long. I distributed our rubric (Appendix B) for grading the final videos so students could see each metric by which the final video would be judged. We explicitly verbalized our learning outcomes and defined critical thinking. For the purposes of this assignment, we embraced a definition of critical thinking adopted by other biological and physical science disciplines: The ability to thoughtfully incorporate various data and other information into the problem-solving, decision-making, or argument-posing process (Holmes et al., 2015; Quitadamo & Kurtz, 2007). The formalized learning outcomes are based on the taxonomy of educational objectives (Bloom & Krathwohl, 1956) and include:

- Apply new types of information—such as interviews, photos, diagrams and voiceover—to convey a visual and audio message;

- Evaluate outside sources, such as USDA data, credible reports or articles, and use to justify or refute your argument;

- Integrate resources into your film that are not protected by copyright and support your message;

- Create a final film that is CC-BY-NC licensed with a well-developed, supported and articulated message;

- Recall basic concepts from lectures/readings to situate your film’s main message;

- Identify and explain clearly your film’s message or argument;

- Draw connections between concepts in your film and how they relate to the topic of sustainable agriculture.

The first four outcomes align squarely with key aspects of information literacy and can be achieved best with the heavy involvement of an educational professional trained in information literacy standards, including ACRL’s Framework. To achieve each outcome, I established three distinct project milestones, each with a deliverable. Each deliverable’s due date was preceded by a class period devoted to relevant instruction and hands-on learning to set students up for maximum success. Utilizing a constructivist and scaffolded approach inherent to OEP, each milestone built upon the previous one in complexity and scope and required that students expand on their knowledge to create something new instead of a simple reproduction of facts (Wiliam et al., 2004). We utilized informal formative assessment at the submission of each milestone deliverable, enabling students to ask questions as they emerged, and provided feedback in real-time (Sadler, 1998).

The first milestone is the easiest of the three, though still complex. During a lab period, students pitch their idea for their video, rationale for the idea, and a rough draft of the video’s narrative. After each project team presents, at least two peers from the lab and both the professor and librarian offer conceptual feedback on the proposal’s message.

To help students meet the expectations for this milestone, I lead a workshop on constructing a well-articulated and evidence-supported argument several weeks prior to this milestone’s due date. I utilize deliberative pedagogy, or a consensus-type model, in which students work backwards from a given problem to collectively find a solution (Shaffer et al., 2017). I assign each student a hypothetical personal problem—like being offered a dream internship but realizing it was unpaid and therefore unfeasible to accept—and instruct each to seek and apply evidence to articulate a solution. Each student then presents the solution to a partner, who provides feedback on the strength or weakness of its supporting evidence.

In the process of engaging in the dissection of evidence and the construction of arguments, students learn that the mechanisms matter more than the platform or parts. This is a crucial observation for students and helps them understand that the technical skills required when making a video should not overshadow the construction of a solid message. This was a distinct problem that we had observed during the first year of the assignment and underscores the point that in learning, facilitating an appreciation for processes is just as important as emphasizing the final product.

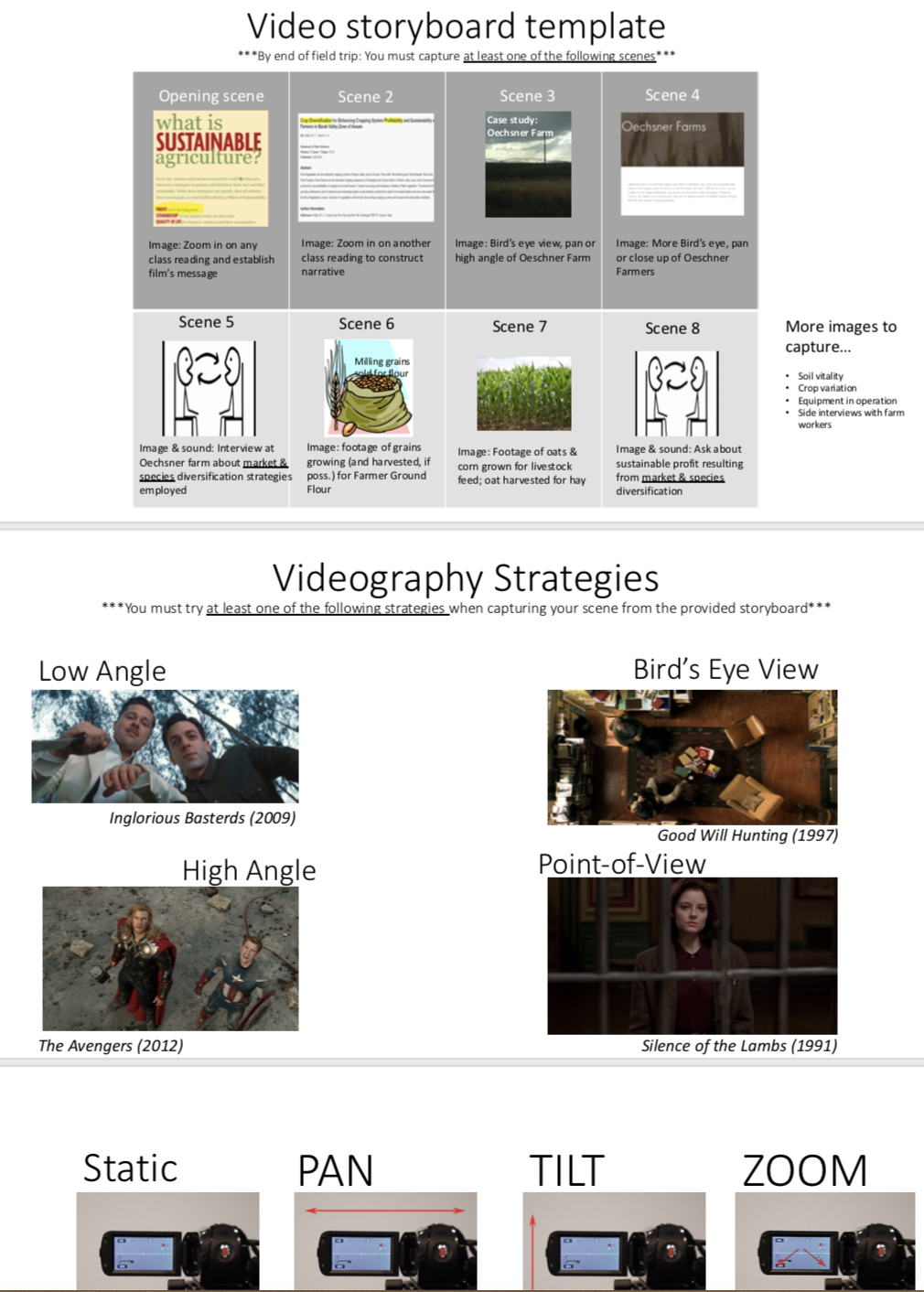

Building from the first milestone, the second milestone is more laborious. Students are asked to work with a classmate to capture practice footage on a class field trip and submit the footage to me for later class review and feedback.

To help students meet expectations for the second milestone, I incorporate active learning videography instruction into an already-scheduled farm field trip during the third week of the semester. This active learning is done out of necessity; I wanted to introduce the concepts early in the semester while the professor needed to schedule field trips prior to the first frost. With more content to cover than time, we combined the lesson with the field trip in one lab period. To facilitate active learning, I distribute a complete storyboard to each pair of students on the bus ride to the farm. Each pair receives the same storyboard, which lays out the sequence of shots required to create a fictional film about the origins and operations of the farm. In true open and participatory fashion, I ask students to brainstorm with their seatmate how they will capture the visual or audio footage needed to illustrate and support at least one of the shots in the storyboard. When we arrive at the farm, I then hand out cameras and audio recorders that I borrow from the library and ask students to spend 15 minutes capturing the footage that they planned on the bus ride to capture. By putting their plans directly into action, students practice their skills in an active and impactful way, capturing the same type of footage that they may need later for their final group video (Felder & Brent, 2009, p. 7). Student footage from this activity is submitted to me afterwards and utilized during an instruction workshop that supports the third milestone.

The third and final milestone is the most daunting of all: each group uploads their final edited video. Those willing to archive their film and assign a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial (CC-BY-NC) license upload their video to eCommons, thereby making it public. Those unwilling to do so upload it to a private Learning Management System open only to the class, without grade repercussion.

To help students succeed with this final milestone, I lead a workshop during a lab period several weeks before the due date on copyright and film editing. During this workshop, I utilize the practice footage the students captured on the field trip and submitted for the second milestone. Two library colleagues with experience using video editing software join me for this final workshop to address the high volume of personal questions and need for hands-on help from the students. For the first part of the workshop, I provide a 15-minute lecture on the importance of licensing and what to consider when creating and reusing content. For the second part of the workshop, I teach students how to perform basic functions in two software programs, including iMovie (a commercial editor standard to Macs) and OpenShot (an open-source video editor compatible with Mac, Windows and Linux). I then utilize problem-based learning and assign students a ‘problem’ to solve in their choice of either iMovie or OpenShot. The “problem” is related to the footage and audio that they previously submitted following the field trip. Problems range from unstable and shaky video footage, inaudible interviews, fragmented footage with abrupt endings and irrelevant content captures.

Once they have solved the problem by utilizing the functions of an editing program (such as dampening sound, stabilizing footage, or combining several clips), the final scenes are complete for each storyboard frame of the video on the farm. In the process of resolving each problem, students simultaneously review and correct the work of their peers while recognizing the agency that they have to create, manipulate and give meaning to both their content and the content created by others. For the third part of the workshop, students work on their final project while I circulate to answer questions and address technical issues. At this point, the room is energized and the spirit of collaboration is palpable. As students work with footage that they have captured, they continue to reconceptualize their role as content creators.

At the conclusion of the workshop, I review the consent form that our Director of Copyright created and ask students to sign if they plan to deposit their final film into eCommons. Students are encouraged to ask questions before signing and I review the benefits and potential drawbacks of archiving it in eCommons, making it clear that consenting is optional and detached from the grading rubric. Benefits include: the assignment of a stable identifier to each video, descriptive metadata (including duration and keywords) for each video that aids in its discovery within the platform, a streaming version that speeds play time and indefinite hosting within the class collection in eCommons. An additional benefit (that some students view as a drawback) is that eCommons is indexed by several search engines, including Google, thus further enhancing the likelihood of discovery from outside the repository.

Each year, 2-3 students typically opt out of publishing their final film in eCommons, citing the desire to prevent their parents or future employers from discovering the video. One student has also asked to temporarily remove their video from the repository so they could submit it to an international film festival, where guidelines stipulated that the video could not be submitted or housed elsewhere. As students formally sign a consent form and agree to an actual license for their work, they further recognize the power and agency that they have in creating meaningful content in video form.

Film Festival

On the final day of class, we host a film festival in a large library lecture room complete with a popcorn maker and white lights. Each group presents their video to the class and invites questions. Films that were archived in eCommons are streamed directly from the repository, reducing the load time necessary between videos and further illustrating to students the public nature of their work. Students also score each video based on a rubric provided to them in a Qualtrics-based web form; the cumulative score determines the top ten ranked videos for the year. Following the festival, the top ten videos are noted within the collection in eCommons for further recognition.

Over the years, music videos, comedic parodies, documentaries, and stop-film animation short films have been created on a wide range of topics. Topics have included farm management practices like crop rotation, manure management and soil tillage, and also more social topics like food deserts, dining hall waste, and the aging demographic of farmers. When introducing students to the concept of sustainable agriculture at the start of a new semester and the video assignment itself, we utilize past student videos. The videos have also proven effective as a means of outreach when meeting with new faculty on campus and explaining the multitude of instruction services that liaison librarians offer. When meeting with librarian colleagues at different institutions interested in the concept of “openness”, I rarely miss an opportunity to share the URL to the eCommons repository where the collection of 137 openly licensed student videos are housed. Indeed, several videos boast more than 700 views from more than 10 countries, making the case that these videos are useful and worthwhile to many people, not just the students that make them. The usage statistics also underscores a reality for students: they have a serious responsibility to consume and create content ethically. Though daunting, this realization is empowering.

Assessment

The three project milestones each yield various outputs, that are assessed in several ways, some of which was described previously. In summary, the first milestone includes a peer review where students critique the strengths and weaknesses of an evidence-based solution to a hypothetical problem. The second milestone includes another form of peer review where students are given problematic video and audio footage captured by their peers and are asked to resolve the issues with their newly acquired technical editing skills. And the third milestone includes both a peer review and instructor grade based on the previously supplied rubric.

In addition to assessing student competencies, I assess my own teaching efficacy and the impact of the video project. The professor includes questions on the student end-of-semester course evaluation about each instructor’s efficacy, including our ability to clearly and effectively explain new concepts and our willingness and ability to answer questions. We also ask students to rank in order of preference each assignment for the course, including the video assignment. The video assignment routinely ranks in the top half of all assignments. Feedback over the years has included: suggestions to increase the percentage of the assignment in the overall course grade (which we did), suggestions to provide more hands-on editing help (which we have), and suggestions to improve the peer-to-peer review process (which we have implemented). Each year’s evaluation brings new suggestions, resulting in an ever-evolving assignment and relatedly, open and adaptive instructional strategies.

Considerations for the Future

As one might imagine, this project is time-consuming and dependent on several factors. Chief among them is the librarian’s ability to fully engage with the class and the faculty member’s willingness to devote significant class time to such a project. The project now accounts for 20% of the student’s final grade in the course, a slight increase from its original 15%, further signaling from the professor the value of the assignment. Without the professor’s support and unwavering embrace of new pedagogical strategies, as well as his recognition of my contributions and co-instructor status, the project would suffer the same lackluster results as it did in year one. The feasibility of devoting significant time year after year is a real consideration for others considering such a project. The feasibility of creating meaningful videos derived from a course’s subject domain is another consideration.

Applied classes with hands-on components may lend themselves more to video projects than other classes. Indeed, as the project in PLSCS 1900 has grown and developed, other applied classes within the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences have sought my assistance to develop similar video projects, including in the Viticulture and Enology Department and the Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Department. Large classes with enough enrollment to enable small groups of 2-3 students may lend themselves to labor-intensive video projects. The advantage of having a larger class is that work can be distributed among several students and the students can benefit from the skills of their teammates. In general, when consulting with professors about a video assignment, I strongly recommend group videos because of the significant time it takes to create a high quality video. However, I also strongly encourage that group formation be at the discretion of the students. In other words, while the professor can and should encourage group work, he or she should ultimately let students decide if they want to work in a group and with whom they want to work. In past experience, group problems arise most frequently when groups are forced upon students, and students with different learning abilities or styles are forced to work in groups that may not recognize or respect the differences.

An additional consideration of course is the local climate on each campus, which may dictate the possibility or embrace of video project uptick. As indicated, the land grant ethos of Cornell inspires a certain degree of interest in applied and public-facing course projects. The library has also embraced the role of librarians in such projects. As the interest in librarian-supported video projects increases at Cornell, the library has devoted increased resources to meet the demand. Over the last two years, the job descriptions for several librarians have been re-written to increase the percentage of eLearning responsibilities in their portfolios, including video project support. For librarians looking to clarify the feasibility of such a project on their campus, a conversation with library administration may be the next step. As multimedia skills become increasingly desirable in the workplace and information literacy skills become even more helpful to engage with civic life, the librarian with their relevant skill set is a natural partner to help develop these skills (Raish & Rimland, 2016). Indeed, by adapting our practices to enhance student skills desired by future employers, librarians are embracing yet another argument of Open Education Practices: that industry and education standards become more open and better aligned (Eldridge, 2017).

Finally, an important consideration moving forward concerns the relationships between the librarian and faculty member, and the librarian and student. In the project that I outlined above, I have played a significant role in the teaching and grading of student work. The professor lists me as a co-instructor for the class and recognizes my involvement with the project among his faculty peers. He and I meet regularly to discuss and collaborate on course development. Although I do not receive additional compensation for this work, I benefit from the recognition that comes from being listed as a course instructor; something that is favorably viewed by library administration in the librarian promotion process at Cornell. I also derive more respect from students who view me as their course instructor, and someone from whom they can and should seek guidance and support.

I have been fortunate to work with such a supportive and encouraging professor as well as a supportive and encouraging supervisor. To ensure this success for others moving forward, I encourage outlining expectations with the professor in advance of commencing a video project and clearly delineating each person’s responsibilities. The process happened organically with this project and has evolved over time, but was completely successful because I had a very good rapport with the professor.

Conclusion

Overall, with each course iteration, improvements to the assignment have resulted in more nuanced and unique student-created videos. By incorporating distinct milestones into the project, clearly conveying expectations, and integrating associated active learning opportunities into the class at strategic times, students succeeded. This is evidenced by a high median grade on the project (A-) and active engagement with the assignment throughout the semester. Instead of stumbling with the video medium as they did during the first year, students utilized the medium to enhance and articulate a message. By requiring that students identify a message and utilize evidence to support their argument, we have found that students enhance their understanding of topics first introduced in lecture. And by actively engaging in the production of new knowledge, students engage in deliberate research to find supporting and refuting sources. Open education practices (OEPs) were harnessed in this assignment to promote and underscore students’ role in the creation of content. OEPs also enhanced our ability as instructors to develop student competencies and skills in lasting and meaningful ways for the benefit of those that will consume these videos one day (Knox, 2013b). The heavily viewed OER—on meaningful topics such as solving world hunger, encouraging a new generation of farmers, and tackling food injustice—have undoubtedly been the most significant impact of course to date.

References

Adenle, A.A., Sowe, S.K., Parayil, G., & Aginam, O. (2012). Analysis of open source biotechnology in developing countries: An emerging framework for sustainable agriculture. Technology in Society, 34(3): 256–69.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2012.07.004

Armbruster, P., Patel, M., Johnson, E., & Weiss, M. (2009). Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in Introductory Biology. CBE Life Sciences Education, 8(3): 203–13. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.09-03-0025

Bloom, B.S., & Krathwohl, D.R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. [1st ed.]. Longmans, Green.

Bransford, J., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. (Expanded ed.). National Academy Press.

Burbach, M.E., Matkin, G.S., & Fritz, S.M. (2004). Teaching critical thinking in an introductory leadership course utilizing active learning strategies: A confirmatory study. College Student Journal, 38(3): 482+.

http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A123321909/AONE?sid=googlescholar

Dori, Y.J., & Belcher, J. (2005). How does technology-enabled active learning affect undergraduate students’ understanding of electromagnetism concepts? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(2): 243–79. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1402_3

Ehlers, U.D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning,15(2): 1–10. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/147891/article_147891.pdf

Eldridge, L.B. (2017). Aligning open badges and open credentialing with open pedagogical frameworks to address the growing skills gap. International Journal of Information and

Education Technology, 7(4): 314-318. http://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2017.7.4.887

Felder, R. M., & Brent, R. (2009). Teaching and learning STEM: A practical guide. John Wiley & Sons.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M.P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of

America,111(23): 8410–15. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Holmes, N. G., Wieman C.E., & Bonn, D. A. (2015). Teaching critical thinking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(36): 11199–11204. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.150532

Kenney, B.F. (2008). Revitalizing the one-shot instruction session using problem-based learning. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 47(4): 386–91. http://www.jstor.com/stable/20864946

Knight, J.K., & Wood, W. B. (2005). Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education, 4(4): 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1187/05-06-0082

Knox, J. (2013a). Five critiques of the open educational resources movement. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8): 821–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.774354

———. (2013b). The limitations of access alone: Moving towards open processes in education

technology.” Open Praxis, 5(1): 21–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.36

Kvenild, C., & Calkins, K. (2014). Embedded librarians: Moving beyond one-shot instruction. Association of College & Research Libraries.

Mery, Y., Newby, J., & Peng, K. (2012). Why one-shot information literacy sessions are not the future of instruction: A case for online credit courses. College & Research Libraries, 73(4). https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16242

Murphy, A. (2013). Open educational practices in higher education: Institutional adoption and challenges. Distance Education, 34(2): 201–17.

https://eprints.usq.edu.au/22931/5/ODLAA2013.pdf

OpenShot Video Editor. [Computer software] OpenShot Studios, LLC. https://www.openshot.org

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3): 223–31.

Quitadamo, I.J., & Kurtz, M.J. (2007). Learning to improve: Using writing to increase critical thinking performance in general education biology. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 6(2):

140–54. http://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.06–11–0203

Raish, V., & Rimland, E. (2016). Employer perceptions of critical information literacy skills and digital badges. College & Research Libraries, 77(1): 87–113. http://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/download/16492/17938

Sadler, D.R. (1998). Formative assessment: Revisiting the territory. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1): 77–84.

http://dropoutrates.teachade.com/resources/support/5035b24fecda6.pdf

Sawers, K.M., Wicks, D., Mvududu, N., Seeley, L., & Copeland, R. (2016). What drives student engagement: Is it learning space, instructor behavior or teaching philosophy? Journal of Learning Spaces, 5(2). http://libjournal.uncg.edu/jls/article/view/1247

Shaffer, T.J., Longo, N.V., Manosevitch, I., & Thomas, M.S. (2017). Deliberative pedagogy: Teaching and learning for democratic engagement. MSU Press.

Stripling, B. (2010). Teaching Students to Think in the Digital Environment: Digital Literacy and Digital Inquiry. School Library Monthly, 26(8), 16–19.

Walker, K.W., & Pearce, M. (2014). Student engagement in one-shot library instruction. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3): 281–90.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.04.004

Wiliam, D., Lee, C., Harrison, C., & Black, P. (2004). Teachers developing assessment for learning: Impact on student achievement. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy &

Practice, 11(1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000208994

Willinsky, J. (2006). The access principle: The case for open access to research and scholarship. MIT Press.

Contact Information

Author Ashley Shea may be contacted at ald52@cornell.edu.

Feedback, suggestion, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Video Assignment Rubric

Rubric modified from the International Ocean Film Festival‘s 2014 Student Film Competition Rubric.

|

Criteria |

Rating |

|

||||

|

Exemplary (4) |

Proficient (3) |

Developing (2) |

Undeveloped (1) |

Score (1-4) |

|

|

|

I) Storytelling (message) |

Conveys idea(s) or story to the audience in an effective way. The film is compelling and the purpose of the project – and its relation to sustainable agriculture – is clearly established. Several outside sources, such as (but not limited to) federal data & reports, are integrated to support a strong message. |

Conveys idea(s) or story to the audience in an effective way. The film accomplishes the purpose of the project, and its relation to sustainable agriculture is usually clear. One or two outside sources are used to support the message.

|

Does not convey ideas or story to the audience in an effective way. The purpose of the film is suggested, but it is unclear; link to sustainable agriculture is not well established. Outside sources are used but they do not clearly support a clear message.

|

Lack of idea(s) or story. The purpose of the film has not been identified the video does not match the purpose. No clear link to sustainable agriculture. No outside sources are used.

|

|

|

|

II) Audio/sound |

Audio is balanced between dialogue, music and voice over. Audio is clear throughout the video. |

Audio is usually balanced between dialogue, music and voice over. Audio is clear throughout the video. |

Audio is somewhat balanced between dialogue, music and voice over. Audio is clear throughout the video. |

Audio is unbalanced between dialogue, music and voice over. Audio is inaudible in significant portions of the video. |

|

|

|

III) Video (shot) focus and lighting (Not applicable to Animated films) |

All shots are appropriately focused for the intent of the film. Camera movements are smooth and at appropriate speed. All shots have appropriate lighting. |

Most shots are appropriately focused for the intent of the film. Camera movements are smooth and/or at appropriate speed. Most shots have appropriate lighting. |

Many shots are not appropriately focused. Motion shots are fairly steady. Some shots have inadequate light.

|

Few shots are appropriately focused and are not shot with intent. The camera is not held steady. Many shots have inadequate light.

|

|

|

|

IV) Production (transitions, editing, effects) |

Excellent use of transitions and effects; very smooth blend between scenes; invisible edits. |

Good use of transitions and effects; smooth blend between scenes; edits are unobtrusive. |

Poor use of transitions and effects; inappropriate blend between scenes; edits are disruptive. |

Little to no use of transitions and effects; distracting edits between scenes. |

|

|

|

V) Visual appeal (overall aesthetics) |

Excellent composition. Uses effective shots. Cinematography conveys messages about characters and story.

|

Good composition. Uses some effective shots. Cinematography conveys some messages about the characters and storyline.

|

Minimally acceptable composition. Shots are not very effective. Cinematography does not contribute to character development or storyline/message.

|

Poor composition. Weak, repetitive or poor shots. Cinematography contains no messages about characters or storyline/message.

|

|

|

|

VI) Originality and creativity |

Film shows evidence of imagination, creativity, and originality. Thoughtfulness to the style and mood that suits the film. The content and ideas are presented in a unique and interesting way.

|

Film shows some evidence of imagination, creativity, and originality. Thoughtfulness to the style and mood that suits the film. The content and ideas are presented in an interesting way

|

Film shows little evidence of imagination, creativity, or originality. Minimal thoughtfulness to the style and mood that suits the film. Film shows an attempt at originality in part of the presentation.

|

Film shows no evidence of imagination, creativity, or originality. No thoughtfulness to the style and mood that suits the film. Film is a rehash of other people’s ideas and/or images and shows very little attempt at original thought. |

|

|

|

VII) Timing/pace |

All clips are just long enough to make the point clear with no slack time. The pace captures the audience attention and the “mood” of the content.

|

Most clips move at a steady pace. Most transitions between scenes are thoughtfully executed.

|

Some clips move at a steady pace. Some clips are edited to remove slack time. Transitions between scenes are somewhat thoughtfully executed.

|

Video clips are too long and do not advance the storyline or too short and leave out essential action. Transitions between scenes do not show evidence of thoughtful execution.

|

|

|

|

VIII) Overall impression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total score |

|

|||||

Appendix C

Figure 2

On-Farm Storyboard Template and Videography Techniques Handout

Appendix D

FERPA Release

Student Video Project FERPA Release

Name of Student:

Student NetID:

Pursuant to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), I hereby authorize Cornell University to release the following educational records and information (identify title of the video):

The project identified above will be made available to the public in an exhibit in Mann Library, through the Cornell institutional repository (currently eCommons) and online. While I understand that it is preferred that I deposit the educational work identified above, there are times when it may be simpler for Cornell University staff to do it on my behalf. I hereby authorize the deposit of the educational work identified above on my behalf.

I authorize Cornell to distribute my work under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommerical license (see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). This allows the library and others to distribute and use the video so long as they give me credit and it is for non-commercial purposes. Otherwise, during the period of copyright protection (currently 70 years after my passing), people wishing to make commercial use of my video will need to contact me or my estate in order to secure permission.

I am requesting the release so that my project can be used as an example of work conducted and to further the Library’s outreach and the work of others. I hereby authorize the Cornell University Library to take any necessary actions to accomplish this purpose.

I represent that I am the creator of this video and that the video is original and that I either own all rights of copyright or have the right to deposit the copy in a digital archive such as eCommons. I represent that with regard to any non-original material included in the video I have secured written permission of the copyright owner(s) for this use or believe this use to be allowed by law. I further represent that I have included all appropriate credits and attributions.

I understand that (1) I have the right not to consent to the release of my education records, and that (2) this authorization shall extend to Cornell University and its grantees, lessees, or licensees in perpetuity unless revoked by me, in writing and delivered to the Cornell University Library. Any such revocation shall not affect disclosures previously made by Cornell University or its licensees prior to the receipt of any such written revocation.

Student Signature

Date

Appendix E

Figure 3

Student Video Repository