Open Pedagogy as Open Course Design

Invitation to Innovation: Transforming the Argument-Based Research Paper to Multimodal Project

Denise G. Malloy and Sarah Siddiqui

Authors

- Denise G. Malloy, J.D., Ed.D., University of Rochester

- Sarah Siddiqui, University of Rochester

Project Overview

Institution: University of Rochester

Institution Type: private, research, undergraduate, graduate

Project Discipline: Academic Writing

Project Outcome: public student research presentations

Tools Used: ACRL Framework, Design Thinking, LibGuides

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Course Learning Objectives

- Course Description

- Course Syllabus and Schedule

- Lesson Plan

- Images

- Video

Introduction

At the University of Rochester, all students must satisfy the Primary Writing Requirement (PWR). Although a small number of students request to substitute or transfer a course to fulfill this required course, the vast majority of students take one of the four-credit, theme-based writing courses (WRT 105), typically during their first year of college. The WRT 105 course is offered through the Writing, Speaking, and Argument Program (WSAP) in the fall and spring semesters. Each course theme is unique and developed by the instructor. As a part of developing the course, instructors curate the readings and develop both informal and formal writing assignments to scaffold writing skills. New hires in the WSAP and graduate students who will be teaching in the program are required to take the summer Writing Pedagogy course to provide structure and feedback in the course development process.

Regardless of the theme, each course must meet the PWR Learning Objectives (see Appendix A for full text of PWR Learning Objectives) which include effective writing process, critical awareness of one’s own rhetorical situation, strength of argument, working with sources, and writer’s textual choices. All sections require students to develop their own authentic research question within the course theme and conduct scholarly research. During the semester, students also engage in reflection about the writing process and give, receive peer feedback for drafts of papers, and revise and edit work for a final polished draft. All sections work towards the shared goal of an 8-10 page, argument-based research paper. During the semester, students in WRT 105 produce a total of 18-20 pages of polished writing.

While students demonstrate their research and writing through their written formal assignments which are uploaded on Blackboard, their work is ultimately for a singular audience—the instructor. By transforming their papers into interactive, multimodal presentations, students are able to disseminate their knowledge to a wider academic community. Through generating a unique, student-driven interpretation of their research, students engage more deeply not only with their content, but the academic community as a whole. This allows for students to not just be consumers of information, but also creators of knowledge.

WRT 105 course: Creativity, Innovation, and Imagination

The Four-Paper Model Writing Course

The WRT 105 course Creativity, Innovation, and Imagination was developed to explore a broad array of issues, ideas, and debates related to creativity, innovation, and imagination. The catalogue description, in part, outlines the course as follows:

Humans have long been fascinated by the process of creating works of art, writing prose and music, or developing innovative solutions to complex business, scientific, and technological problems. Although unrelated by topic, they share the common theme of harnessing the power of creativity, innovation, and imagination. But what is creativity? Who has it? And who really needs it? … Formal papers will be developed through a process of self-reflection, peer response, and revision, as you work toward your 8-10 page, argument-based research paper. (Appendix B—full course description)

This course was first offered in the fall semester of 2017 and has been offered during the fall and spring semesters as part of the theme-based writing courses in the Writing, Speaking, and Argument Program at the University of Rochester. In the first three semesters of this course, the instructor utilized the four-paper model for the semester, which is framed by four formal writing assignments. The skills developed in each of these assignments built upon one another leading up to the final paper, which was the 8-10 page, argument-based research paper. To further scaffold student learning, 10 informal writing assignments were part of the assignment progression.

For each formal assignment, students turned in a first draft for feedback, but not for a grade. Students worked with a peer, assigned by the instructor, for one feedback cycle for each paper. In addition, the instructor provided detailed feedback. After the peer and instructor feedback, writers then had the opportunity to revise their work before turning in the final paper for a grade. Students also engaged in reflective writing on their process for each draft and final version of their formal assignments. (See Appendix C for links to Fall 2018 Syllabus and Course Schedule for the four-paper model.)

Transforming the Course to the Three-Paper Model and the Pop-Up Research Presentation

After visiting the WRT 105 pop-up research presentations in Evans Lam Square, located on the first floor of Rush Rhees Library, the instructor decided to explore the possibility of revising her course to the three-paper model. This would allow for collaboration with research librarians and a research presentation opportunity for students. The open floor plan of Evans Lam Square, with mobile furniture and three digital screens, allows flexibility for hosting events and makes Lam Square a perfect spot to hold “pop-up” events (see Fig. 1). Pop-up programs are designed to be unexpected, timely, seemingly spontaneous, time-limited, and focused on a specific purpose. The events are meant to capture the attention of their audiences in new and different ways, leaving attendees with the feeling that they have been a part of something unique.

The content of the pop-ups relates to a variety of topics, but is aligned with curricula, resources, collections, and library collaborations. Therefore, while the theme may be about a course assignment, the event is open to anyone who happens to be passing by the area at the time. The increased exposure benefits the library, faculty, and students. As of Fall 2018, the pop-ups organized ranged from informational interviews and conversations about academic honesty to academic “comic cons,” showcasing the research done by students for a comics and culture writing class.

In brainstorming sessions with research librarians, the instructor noted that with the four-paper model of Creativity, Innovation, and Imagination, students had wide latitude in the choice of topics that related to the course theme for the 8-10 page research paper. However, the option to transform the research paper into a new modality did not exist. While a short, in-class research presentation gave students the opportunity to share their ideas with their classmates—typically as a PowerPoint slide show—it did not allow them to reimagine their research papers in a new and unique, student-designed format. This reimagination would demonstrate students’ understanding of their research paper for a wider audience. By engaging in the process of reimagining their work in a new interactive format, students were able to demonstrate the depth of their understanding and serve as creators of knowledge in alignment with the principles of open pedagogy.

iZone Planning

During the brainstorming sessions, the research librarians also suggested incorporating a class session in the iZone to support, scaffold, and create space for the transformation of student research papers into multimodal projects. The Barbara J. Burger iZone in Rush Rhees Library is an innovation hub and co-working space where students go to explore and imagine ideas for social, cultural, community and economic impact. It is divided into several sections such as large, open spaces for workshops, booths for smaller groups, and closed “project rooms” for medium-sized groups wanting to work in private. At different points during the semester, the staff in iZone organize a variety of talks and brainstorming sessions relating to design-thinking, prototyping, screw-up nights and more to inspire innovative thinking and ideation.

The consequent ambience in iZone seemed to be a perfect match for the course theme of Creativity, Innovation, and Imagination. The course instructor and librarians met the iZone staff at the beginning of the semester to plan the session and content.The objective was to introduce the students to the iZone and the concept of pop-ups. In addition, the instructors wanted to involve students in planning for the pop-up event, the setup of Lam Square, the formatting of their presentations, and the promotion of the event.

The goal was to give the students autonomous support for the projects which corresponds with the principles of the Self-determination Theory (SDT). By making students feel that they have a say in what the end product would look like, one can get “higher quality engagement, performance and positive experience” (Ryan & Deci, 2016). This can be achieved by motivating students intrinsically to willingly and actively participate which, per SDT, is sustained by satisfaction of the “basic psychological needs” for “autonomy, competence, and relatedness” (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009).

Giving students the opportunity to transform their research papers into a unique, interactive project fits perfectly with the course themes of creativity, innovation, and imagination. The opportunity to actively reimagine their work gives students ownership and agency over their learning. This transformation was framed by the principles of open pedagogy. According to Conole (as cited in Hegarty), there are five main guiding principles: collaboration, communication, developing collective knowledge, creating new scholarship, and innovation of ideas (Hegarty, 2015, p. 3). Transforming the course in this manner enabled students to actively engage in these five principles as they developed their own research in a new modality.

Several factors played a key role in transforming this course into the three-paper model. In addition to creating the space for students to reimagine their work in a non-textual format, another key consideration was having two rounds of feedback (from their peer team and the instructor) to inform the revision process. The instructor was interested in assessing whether multiple feedback cycles would be more effective in transforming writer-based prose into a reader-based final product. The ten informal assignments from the four-paper model were still utilized in the course to scaffold student learning and skill development. An experiential, hands-on class session in design thinking and prototyping was planned to be held in the iZone in April 2019. During the iZone session, students envisioned and implemented plans for the pop-up presentation. Students also had the chance to develop multiple iterations of their multimodal projects with time for prototyping. (See Appendix D for links to Spring 2019 Syllabus and Course Schedule for the three-paper model.)

Collaboration with Librarians

In addition to the revisions made to the syllabus (such as holding sessions in iZone), the two collaborating librarians were added to the course Blackboard as Course Builders. This was useful for keeping up with any modifications made to the class schedule/syllabus, and the librarian(s) could post announcements regarding the class preparations in advance. These two librarians were assigned specifically to this instructor and all three sections of her WRT 105 course. The librarians’ names, contact information, and links to their respective library pages were also included in the syllabus. A library resource guide, or “libguide” was also created for the class and linked to Blackboard. Having worked with this team in previous semesters, the instructor regularly emphasized the value of consultation with the course librarians during the research process.

Prior to the first library session, the students had identified one or more areas they were interested in researching. During the class, they were introduced to methods for finding and evaluating relevant resources for their topics using the library website and databases. The two librarians assigned to the class shared various strategies, stressing that research is an iterative process and that based on their search results, the students would be revising their statements into research questions. This ties into the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Framework for Information Literacy (American Library Association, 2015), in particular to the concepts of “Searching as Strategic Exploration” and “Research as Inquiry.” The complete lesson plan is included in Appendix E, Lesson Plan for Library Day. With the tips learned in this session, the students had some time to think and build on their research before the next session held a month later in iZone. During this period, some students had one-on-one consultations with either librarian to further refine their searches.

Preparing Students for iZone/Scaffolding of Transformation into Multimodal Assignment

After the class started formulating and finalizing arguments for their research papers, discussions related to the transformation of their research into a multimodal presentation for a new audience began. The purpose of the multimodal assignment was for students to contextualize their research in a fashion that would most effectively communicate their argument in a primarily non-textual format. In-class brainstorming sessions allowed students to develop a preliminary working list of possible ideas for transforming their work. During the brainstorming session to conceptualize the non-textual possibilities, students suggested the following: infographics, podcasts, short films, drawings, 3D representations, creating a game, writing and performing a song, and poetry. While the list was not exhaustive, it did provide a framework for student thinking and served as a springboard for ideas for the transformation project. After that session, students were asked to complete an informal writing assignment articulating three possible ideas for transforming their research. In addition, they were asked to write a short argument for each possible choice explaining why that particular modality was best for conveying their argument. In developing their ideas, students were also asked to consider needed materials and the time frame to complete and present the project. The informal writing was to prepare students for the iZone session where they would explore their choices and develop a prototype.

The iZone Session

After one pre-semester brainstorming meeting with the collaborating librarians and iZone staff, another meeting took place to finalize plans for the iZone class session in April. During the second meeting, the lesson plan was developed. As part of the plan, the group created a facilitation plan for each lesson segment (see Appendix F, Lesson Plan for iZone Class). This approach allowed the iZone staff and the librarians, Kim Davies Hoffman and Sarah Siddiqui, to alternate leading the activities with the instructor circulating through the groups.

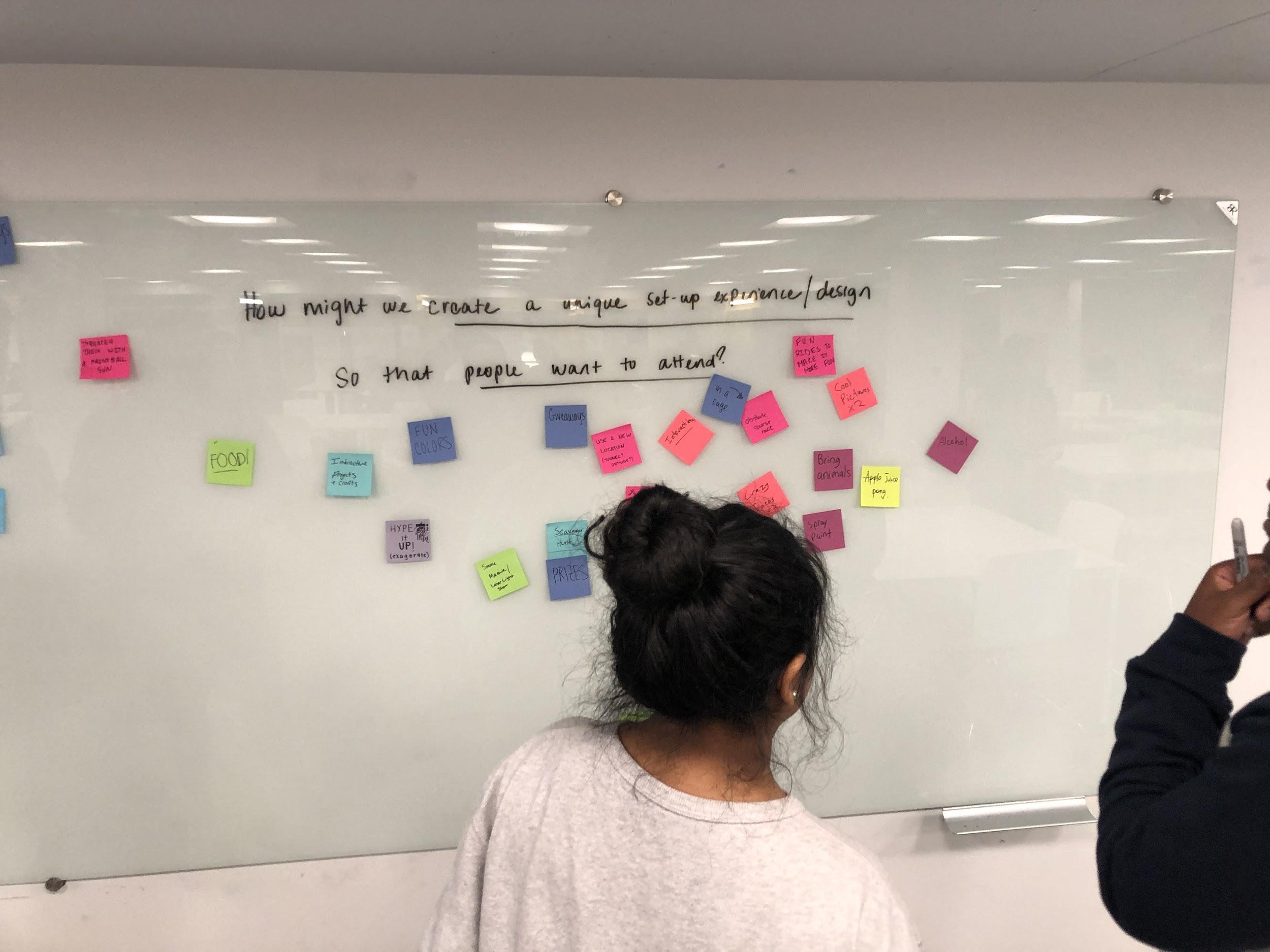

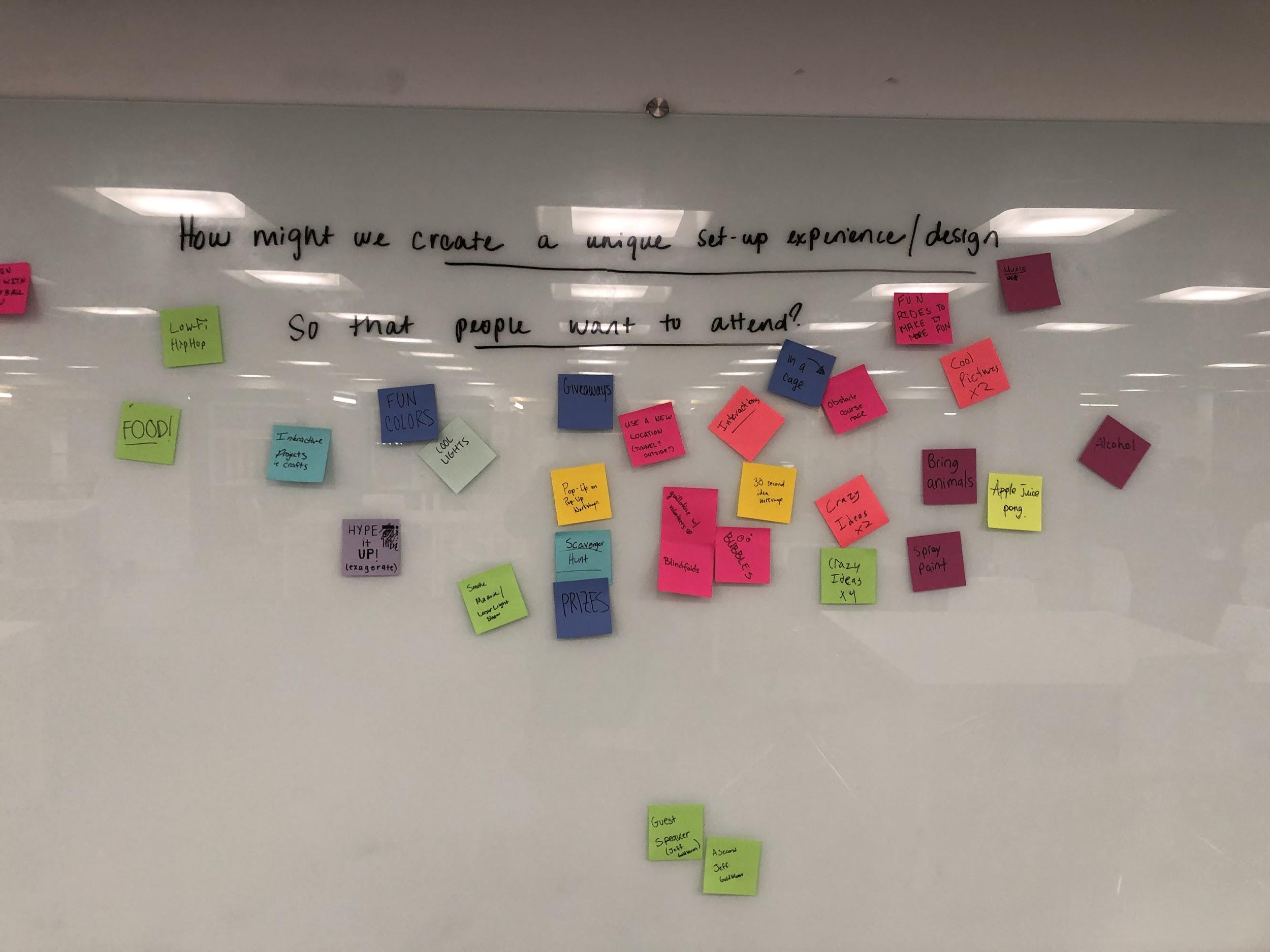

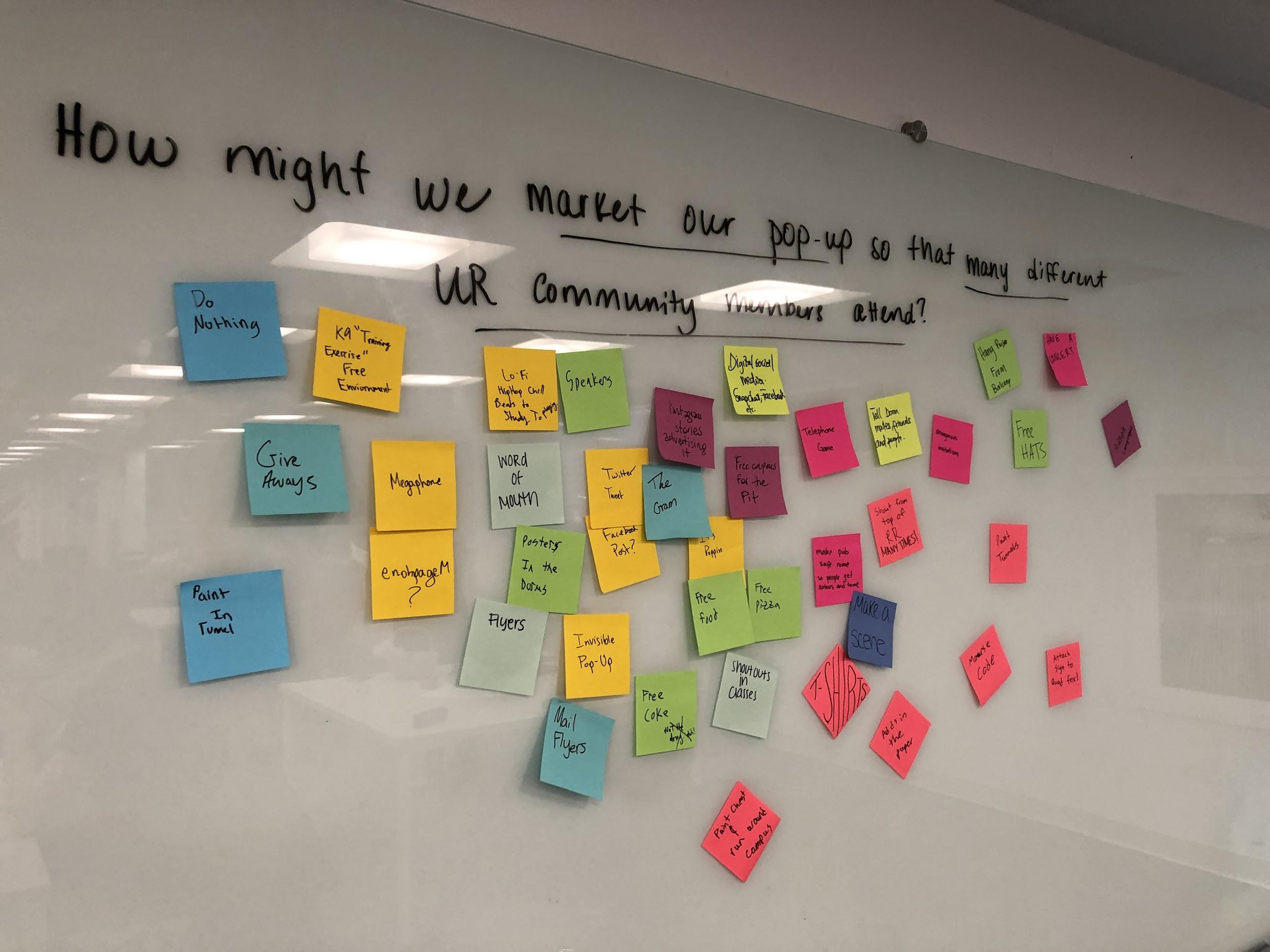

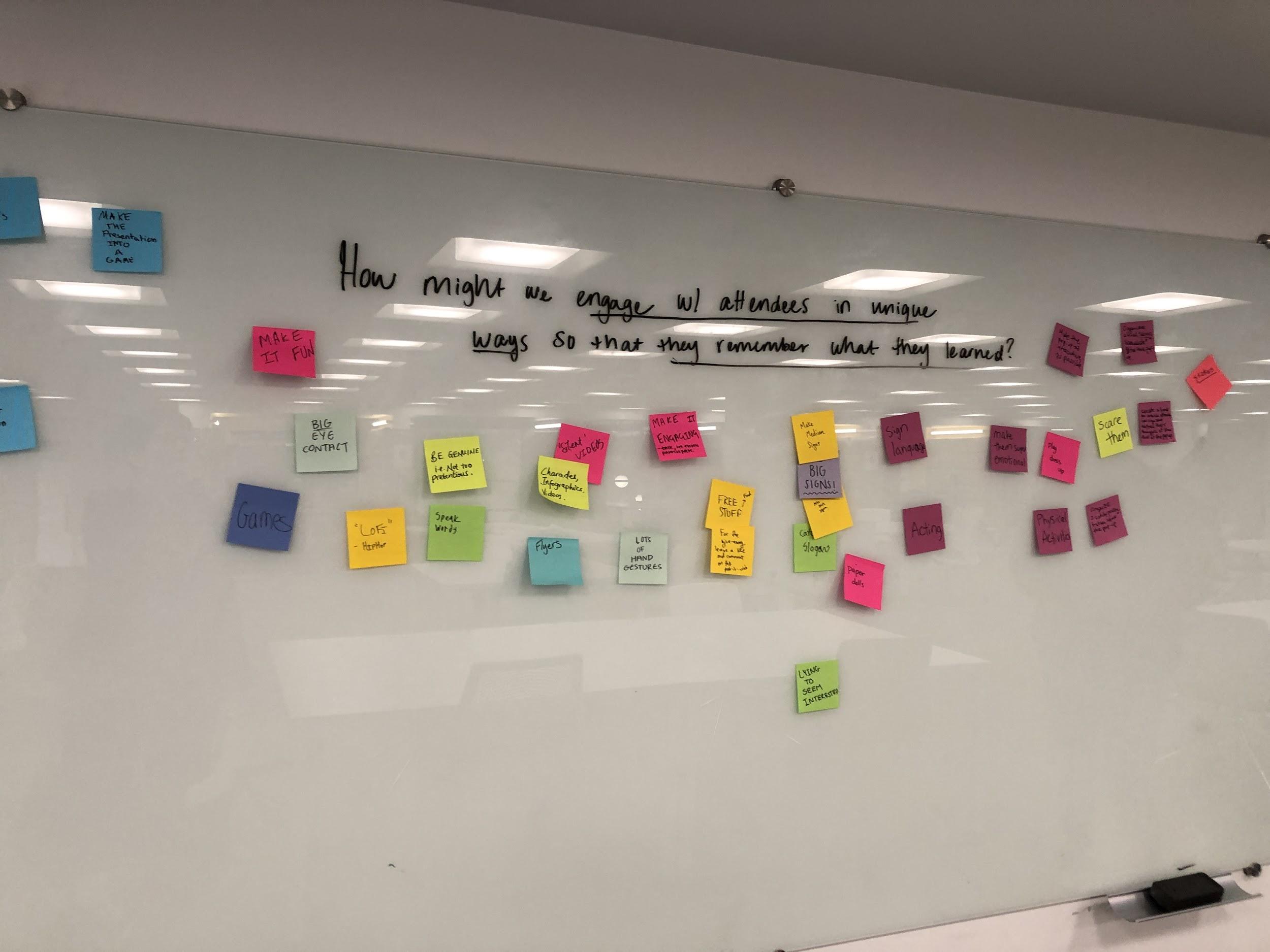

On the day of the iZone session, the students were first introduced to a “yes, and” activity by an iZone staff member. This activity is rooted in a design thinking approach; warming up in this way helped the students enter a state of mind that is open to wild ideas and builds off of one another’s unique perspectives. This fosters idea generation and creative thinking. At this point the course librarians introduced students to pop-ups and encouraged them to apply the activity to designing a pop-up for showcasing their projects (see Fig. 2).

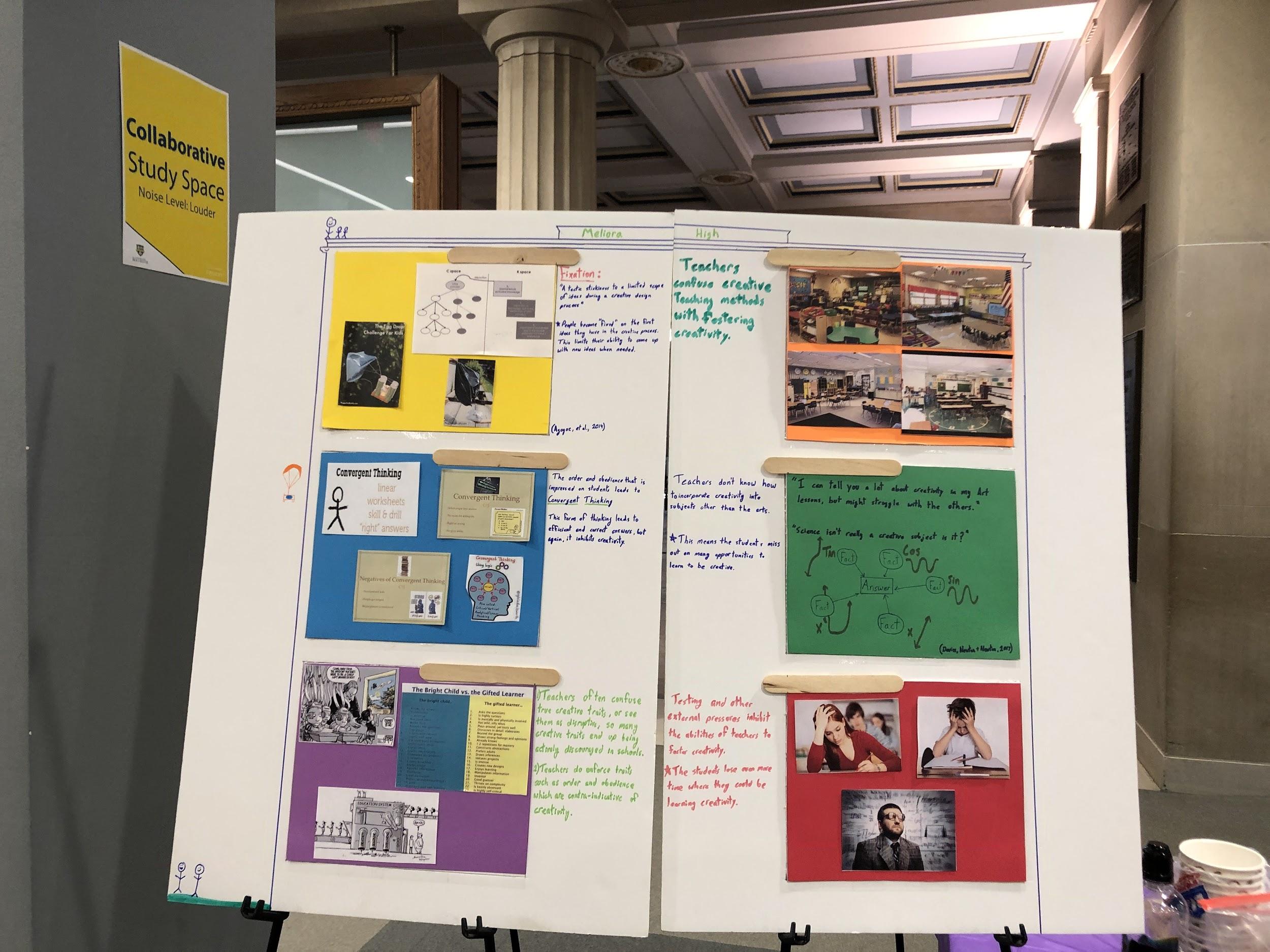

Figure 3

Student-Generated Responses During iZone Session

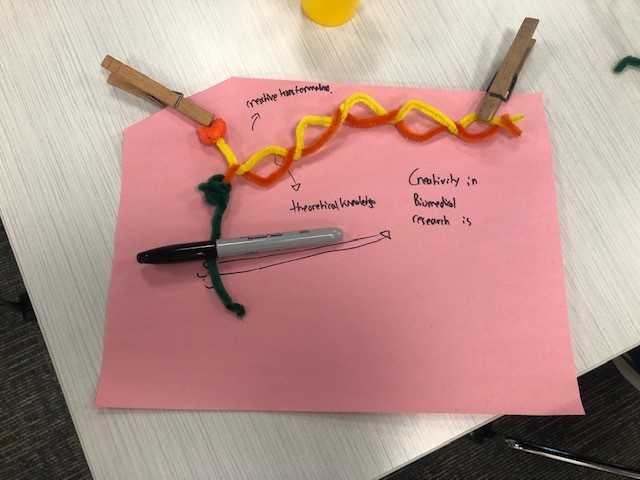

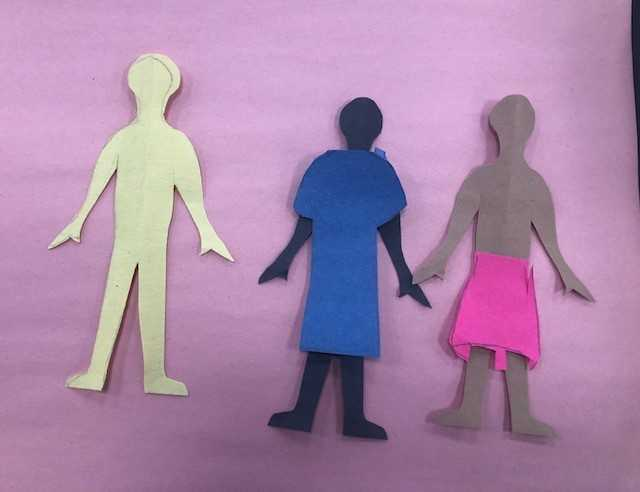

Students examined three facets of the planning process which included marketing approaches, setup and design of space, and ways to interact/engage with the audience (see Fig. 3). Students generated ideas on these topics in small groups in a series of timed activities. Next, students turned their attention to their own research and engaged in a series of activities that would explore ideas in five categories of multimodal expression: music, visual arts, physicality, video, and data. Subsequently, the students utilized materials to explore their ideas and develop a prototype (see Fig. 4). With their individual projects in mind, students then revisited the idea of the pop-up to determine what aspects would allow them to showcase their work. The multiple categories of expression gave the students an opportunity to explore new formats for their final presentations and the choice gave ownership. An important aspect of developing the multimodal project was also considering the materials or technology necessary to create the project along with a realistic time frame for doing so. Given the relatively short time frame to go from an idea to a realized project, it was important for students to be realistic in their endeavors to avoid frustration, undue stress, or disappointment. In considering what might be realistic in terms of a timeframe, students were asked to think about the actual scope of their project as well as their individual school and work schedules. Once these issues were considered, students were encouraged to set achievable goals. In terms of project creation, students were asked to consider the cost and availability of materials needed for their projects.

In this way, student knowledge was enhanced and constructed based on their expertise; thus the agency or ownership from SDT is combined with the constructivist theory (David, 2015) for autonomous, engaged learning. Giving students the opportunity to choose their own topics allowed their enthusiasm for research and writing to unfold naturally and their intrinsic motivation to flourish. The students were passionate about their topics, and several final presentations during the pop-up were inspired by the session.

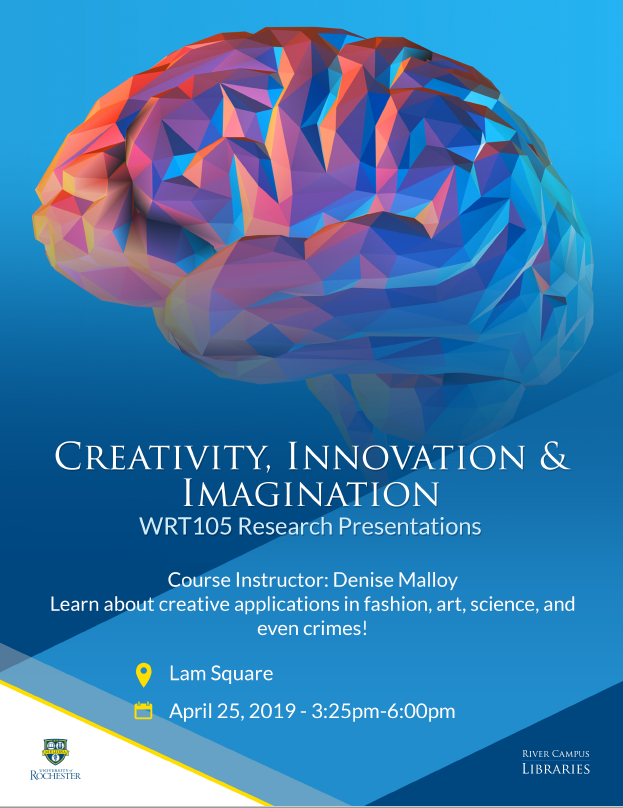

The Pop-Up Session

In addition to the content of the pop-up presentations, the student ideas for marketing and space design during the iZone session were also implemented. Based on student input, a colorful flyer announcing the pop-up event was designed by library staff (see Fig. 5). The course librarians shared notes and photographs of student suggestions with a staff member from the Art and Music Library (located in Rush Rhees) who also designs promotional material for library events. The flyer’s electronic version was shared with River Campus Libraries’ (RCL) digital signage team who added it to the rotating screensavers of upcoming events on public computers across campus. In addition, the flyers were also hung across campus and the event promoted via RCL’s social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) accounts. Students were also encouraged to share the events with their peers.

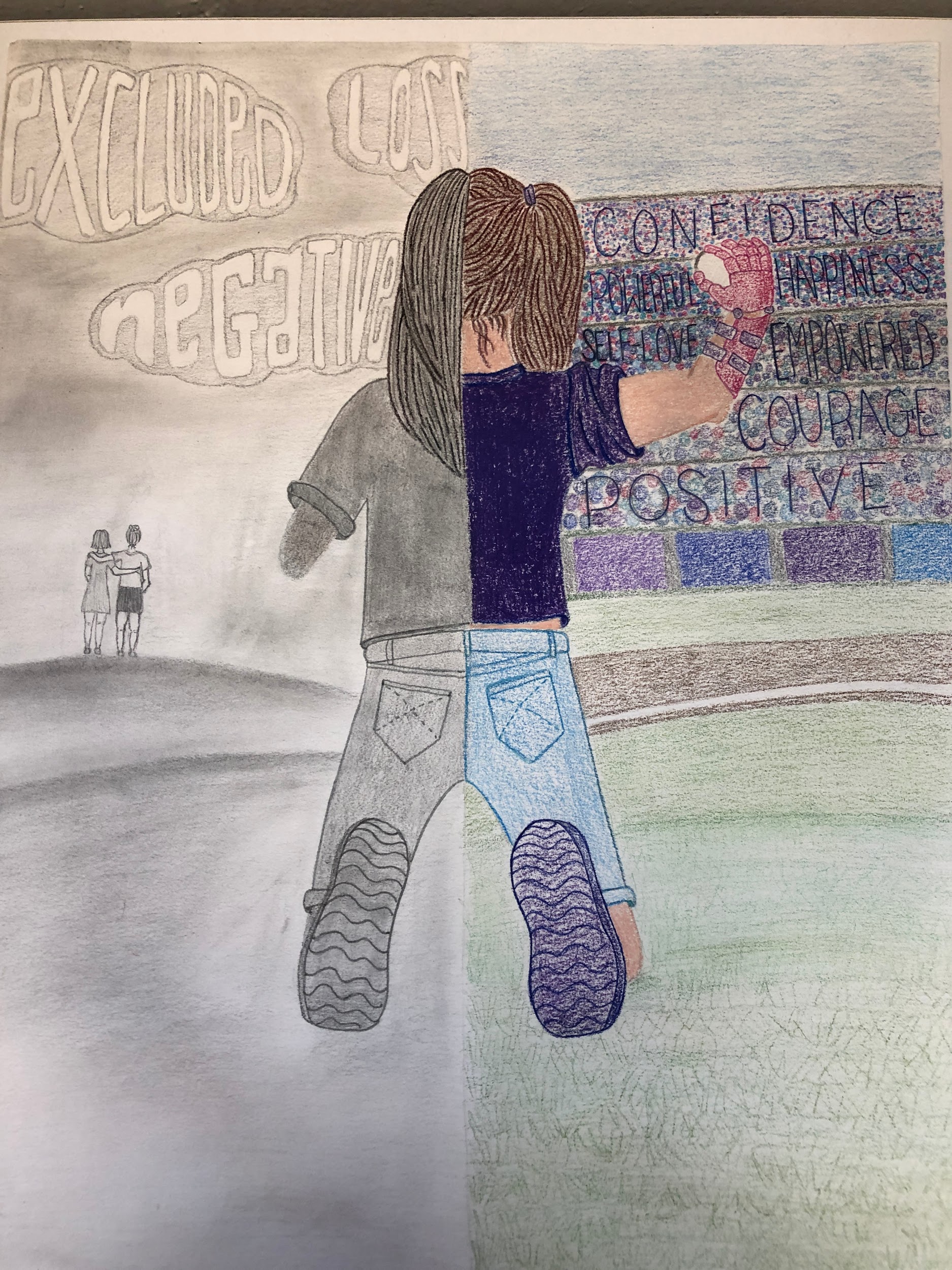

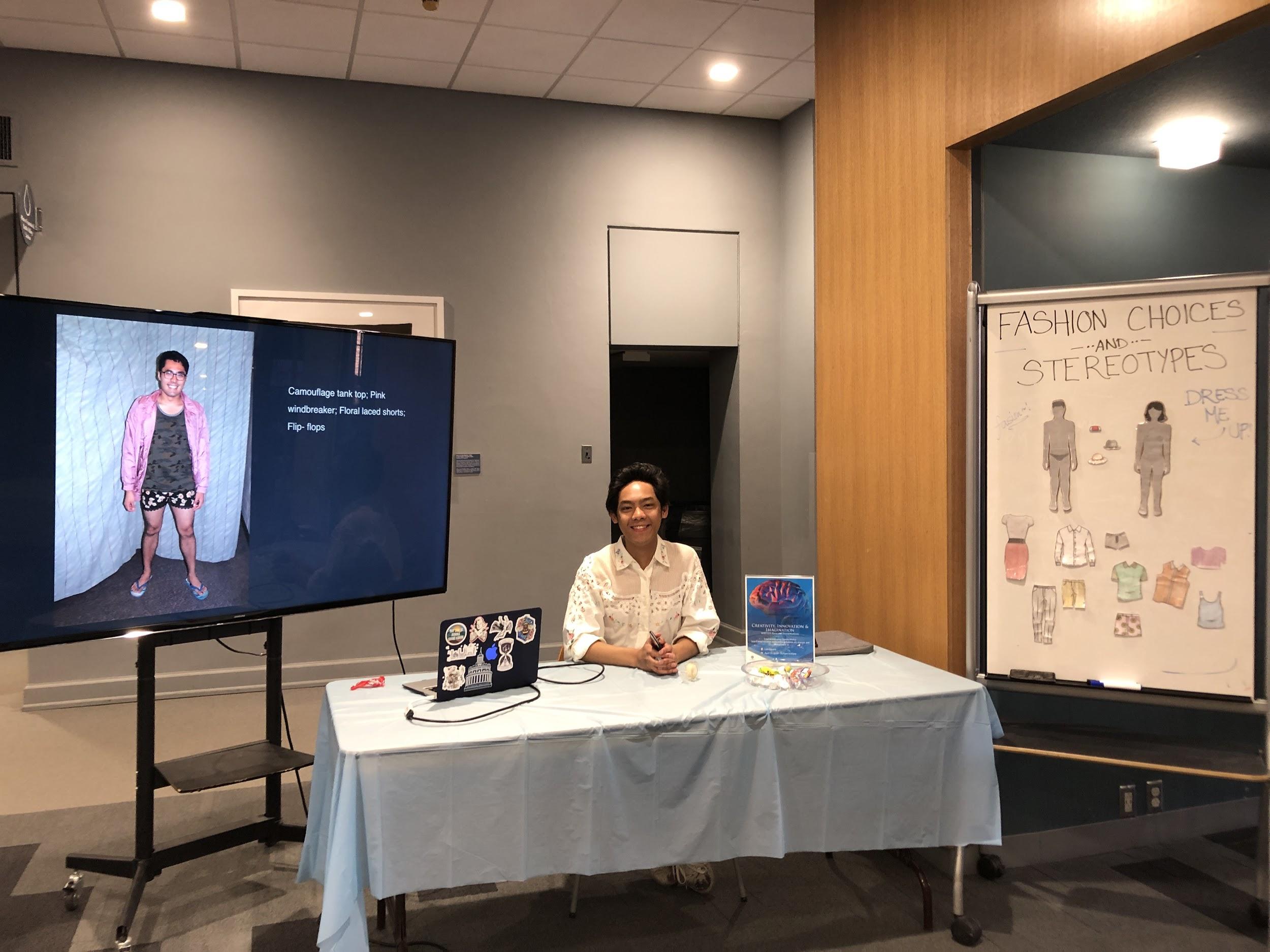

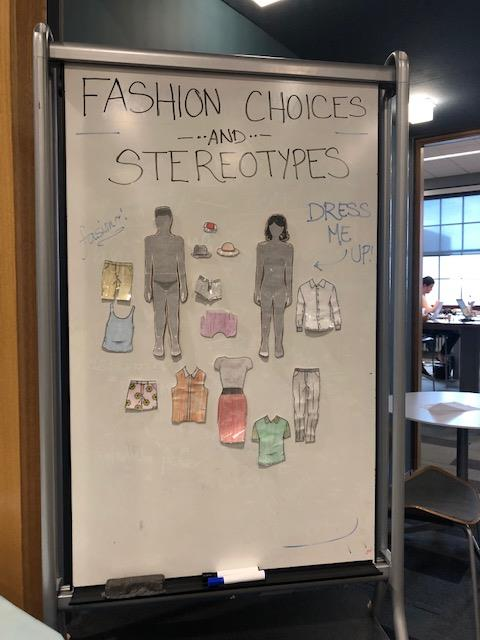

For the event setup, students decided to continue the theme of a colorful presentation to attract visitors, so the tables were laid out with colorful mats and candy. This also served to distinguish the pop-up presentation area and create visual interest. Since most of the students had classes before the pop-up, the librarians and the instructor prepared the space in accordance with the student ideas. More importantly, however, the various formats and rich content of the students’ presentations was the big attraction. As seen in the pictures in the next section, many students were inspired by the ideas generated in class and displayed their works with infographics, music videos, posters, games, as well as interactive artworks. Along with tables of different sizes, the setup also included whiteboards, poster stands, and large digital screens.

Selected Student Multimodal Presentations

Figure 6

Selected Student Multimodal Presentations

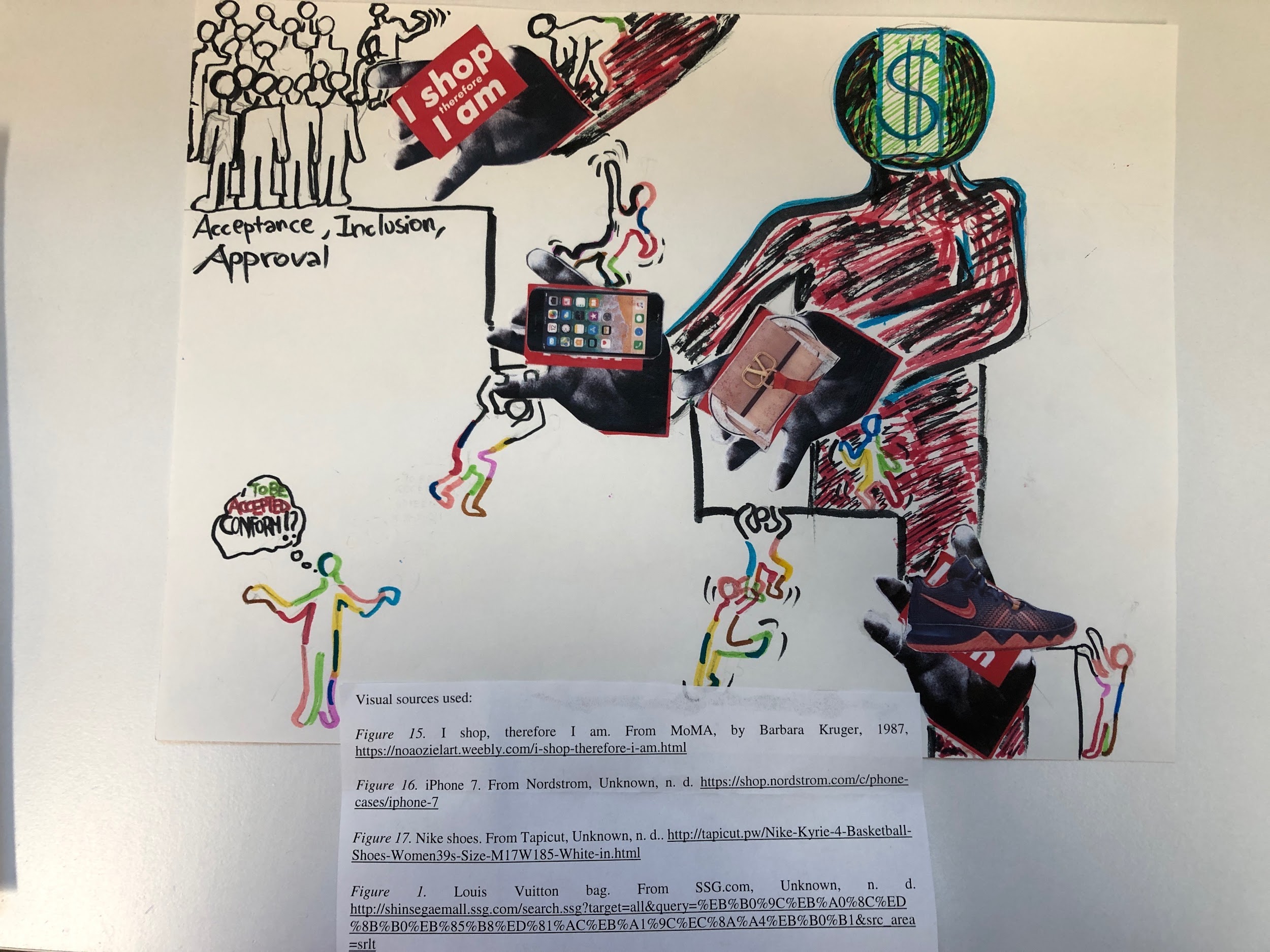

Note. Maggie Dix’s presentation. Research paper: Fake for good: The role of creativity prosthetic development and innovation

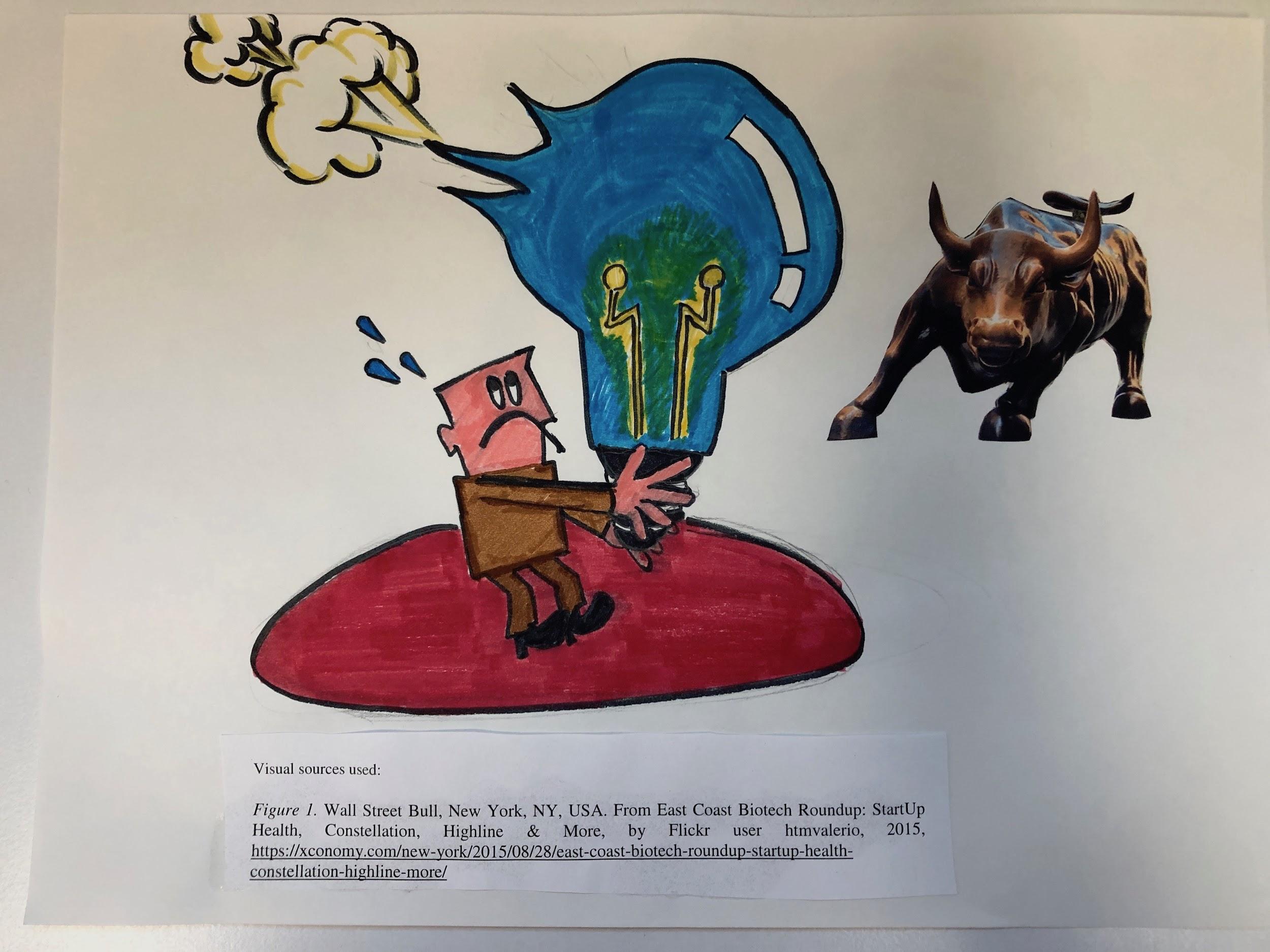

Note. Michele Martino’s presentation. Research paper: The effects of creativity on capitalism

Note. Detailed view of Martino’s work

Note. John Maqui’s presentation. Research paper: Battling Societal Stereotypes Through Creative Choices Made in Fashion

Note. Zach Muench’s presentation. Research paper: Education: Helping or Hindering Creativity?

Reflections

Student Reflection

With each formal assignment, students are asked to submit a writer’s reflection with the first draft and the final version of each paper. These reflections are in response to specific prompts which ask the student to address their rhetorical choices and the research process. At the end of this semester, the instructor asked each member of the class to prepare a written reflection specifically about the process of developing their multimodal assignment. John Maqui volunteered to share his perspectives in a video about his project development (see Fig. 7).

Instructor Reflection

Revamping a course over the winter break was challenging and somewhat stressful. However, the impact of the 3-paper model on student writing was dramatic. First, having two drafts gave students the opportunity to deeply explore the differences between writer-based and reader-based writing. Multiple drafts provided the chance to develop ideas thoroughly and meaningfully and bridge the gap to reader-based prose more effectively than one revision alone. Arguably, students should be creating multiple drafts regardless of the format. However, in reality this is not always the case. Having a built-in mechanism to require multiple drafts made a meaningful contribution to the quality of the final version of student work. In addition, this framework gave the instructor a window into how students think about their research and writing process. This allowed the instructor to pivot and adjust the lessons in class to provide supplemental instruction and mini-lessons as needed for tasks such as writing the thesis statement, developing arguments and counter-arguments, or writing introductions and conclusions.

At first, students expressed apprehension about creating a multimodal project. Some students stated that while they were interested in creativity, they “weren’t creative.” Other students stated that they feared they would not find an interesting way to transform their research. The main concern, however, seemed to center on the fear that the multimodal dimension of the assignment would have a negative impact on their grade. However, after the brainstorming sessions, the iZone class, and subsequent in-class peer team feedback sessions, students were enthusiastic and embraced the process. Several students came up with multiple possibilities and ideas and then expressed that it was difficult to choose. The instructor explained that the assignment would be graded holistically. However, in future semesters the instructor will ask students to complete a self-assessment of the multimodal project and the instructor will grade the written supplemental memo.

Two issues that will need to be addressed in future semesters include the timing of the iZone session and keeping the multimodal presentations shorter for the pop-up session. During the spring semester, the iZone session was planned for April. This timing was not ideal for having students operationalize their ideas for marketing the pop-up session. Next, while students developed a variety of multimodal presentations that were effective in communicating their research, many were far too long for a 75-minute pop-up session. Ideally, visitors should be able to circulate through the pop-up session during the class period and interact with the majority of the students. As a result, each presentation should be three to four minutes maximum. This experience will inform planning and implementation of future brainstorming and iZone sessions.

References

American Library Association. (2015). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. ACRL. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

David, L. (2015). “Constructivism,” in Learning Theories. https://www.learning-theories.com/constructivism.html

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A Model for Using Open Educational Resources. Educational Technology,55(4), 3-13. http://www.jstor.org.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/stable/44430383

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2016). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Contact Information

Author Denise G. Malloy may be contacted at dmalloy3@ur.rochester.edu.

Feedback, suggestions, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

Appendix A

Primary Writing Requirement (PWR) Learning Outcomes

From the University of Rochester’s Writing, Speaking, and Argument Program website

WRT 105, WRT 105E, WRT 105 A & B

Across all academic communities, writing, speaking, and argument enable us to discover, develop, test, and communicate our ideas. To help students develop as academic communicators, the Primary Writing Requirement courses build rhetorical knowledge, which involves “the ability to analyze and act on understandings of audiences, purposes, and contexts in creating and comprehending texts” (http://wpacouncil.org/framework).[2] The objectives below explicate the processes, knowledge, practices, and textual features central to effective academic writing. Our aim is to help students develop as thinking, flexible writers.

Effective Writing Processes

The writer, through a variety of assignments,

- Recognizes that all writers—even the most experienced writers—begin with a “working” draft and rely heavily on revision

- Develops a range of strategies for the composing process (e.g., brainstorming, freewriting, mapping, talking, getting feedback from readers, etc.)

- Drafts, reviews, and revises to discover, develop, and refine the writer’s ideas

- Draws on reflection and feedback to consider how well the text communicates the writer’s intended meaning

- Revises and edits to meet the expectations of the rhetorical situation

Critical Awareness of One’s Rhetorical Situation

The writer, through a variety of reflective activities (e.g., written reflections, genre analysis, discussing writing choices in class or in conferences),

- Considers the audience’s knowledge, needs, and expectations

- Demonstrates awareness of their strengths and weaknesses as a writer

- Reflects on how writing choices may or may not transfer across disciplines and to different rhetorical situations

The composition

- Is accompanied by written reflection that helps the writer make purposeful choices and manage revision

Strength of Argument

The writer

- Understands academic argument as a process of critical inquiry

- Uses argument to develop a perspective on an issue in the context of the larger academic conversation

The composition

- Poses an authentic question or problem

- Develops a debatable thesis that responds to the question or problem

- Uses argument and counterargument to develop, evaluate, and revise the thesis

- Supports argument and counterargument with credible and relevant evidence and sources

Working with Sources

The writer understands the importance of and has gained practice with

- Citing all sources used in the composition

- Using all sources honestly and ethically (e.g., scholarly texts, Wikipedia, TED talks, blogs, screenshots, performances, peer contributions, faculty lectures and course materials, etc.)

- Identifying, evaluating, and selecting sources appropriate to the rhetorical situation

- Developing strategies for keeping track of sources and source ideas so that they can be fairly represented and properly cited

- Identifying and using resources that support the research process (e.g., outreach librarians, databases, source management systems)

The composition

- Draws on sources to help motivate and develop a question or problem

- Contributes to an academic conversation through synthesizing, evaluating, and building on others’ ideas, while ensuring that the writer’s perspective guides the text

- Based on the rhetorical situation, appropriately balances summary and critical analysis of source material

- Uses clear signals (e.g., in-text citations, signal phrases) to differentiate the writer’s ideas from the source material

- Provides the pathway to all sources used in the composition (e.g., through citation and bibliographic information)

Writer’s Textual Choices

The writer

- Recognizes that writers have choices

- Recognizes that all choices shape the writer’s meaning and reader’s understanding

- Through reading and writing, has practice identifying, using, and evaluating different rhetorical choices (e.g., organizational structure, language use, genre, and mode)

The composition demonstrates effective rhetorical choices in

- Composition structure (e.g., organization/ordering of sections, paragraphs and sentences; logical flow and topic development; relationship between given and new information; arranging media elements)

- Language use (e.g., personal voice, academic voice, degree of conformity to standard edited English, code-meshing, amount of technical language)

Appendix B

WRT 105: Creativity, Innovation, and Imagination (full course description):

Humans have long been fascinated by the process of creating works of art, writing prose and music, or developing innovative solutions to complex business, scientific, and technological problems. Although unrelated by topic, they share the common theme of harnessing the power of creativity, innovation, and imagination. But what is creativity? Who has it? And who really needs it? In this course, we’ll write about questions surrounding creativity, innovation, and imagination through the lens of multiple perspectives – from the arts to engineering. Through readings, TedTalks, and podcasts by Sir Ken Robinson, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Elizabeth Gilbert, and others, we’ll look for interdisciplinary themes in creativity. We’ll also use writing to explore how others have used the creative process – from The Beatles to Steve Jobs. Formal papers will be developed through a process of self-reflection, peer response, and revision, as you work toward your 8-10 page, argument-based research paper.

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Madeline Hunter Lesson Plan Template

Professor Name: Denise Malloy

Date/Location: 2/12/2019

Course: WRT 105

Number of students: 14/15

Librarian(s): Kimberly Davies Hoffman, Sarah Siddiqui

Objectives

Students will:

- Connect main concepts within a research question using Boolean and wildcard logic IN ORDER TO effectively retrieve resources from topically-relevant database(s)

- Evaluate discovered resources using criteria for scholarly, peer-reviewed and popular resources IN ORDER TO understand the variety of quality and useful materials within the publication and information landscape

- Combine the themes of various sources to create a summary or topic statement/question IN ORDER TO recognize that scholarship is a conversation between different scholars on a given topic through their publications (your sources)

- Revise an original research question based upon newly discovered resources IN ORDER TO adopt an iterative approach to the research and writing process

Review

(What students already know.)

Anticipatory Set (5 minutes)

KIM: Upon entering the room and being signaled by instructions on the screen, students will add their current research question/topic into a google doc (an example).

So, you already have a research question in mind, but during today’s class, we’ll dig into some of the sources that might help you support and perhaps even tweak and narrow that question.

Body/Procedure

Model (How will you demonstrate skills?)

Check for Understanding

Guided Practice (5min)

- Let’s start finding some relevant material for your tentative topics

- And then we can consider the quality and rigor of the sources you chose.

Introduce 2 methods based on your starting point. Are you still really broad and searching around for a concrete research question or are you pretty clear on the direction where you’re heading? Look at our session today as exploration. Maybe you’ll find an idea as you look through a few sources that tailors your question even more than what you walked in with.

Browse method and targeted topic method

SARAH: DEMO Article & Books—creativity healing (5 min)

Limit to articles, peer-reviewed, subject = psychology or medicine, publication date

KIM: Concept map strategy—video (we will likely demo the concept map live) (10 min)

Time to search—check off or keep in tabs resources that look good to you. (15 min Time Search)

Add sources here:

SARAH: Based on what’s in your google doc chart, let’s begin to evaluate our sources for their quality and rigor. Students look at sources that their successor identified. Using the guide beside you, see if you can figure out if the sources are scholarly and determine some reasons to back up your claim. (Mention this relates to the research journal they are keeping for the class). (10 min eval, depends on how many resources each evals)

Questions before moving on? (5 min discussion)

SARAH: 2 questions in google doc

Student fills in last two columns in the google doc for their own topic (10 min)

With a partner, each student takes 5 minutes to discuss the topic, clarify, and perhaps add more and/or narrow the topic (10 min)

Closure (5 min)

Take away—based on what you found today (only the beginning!), has your research question shifted at all? If so, write down a new question that will get you closer to achieving the next assignment. HOMEWORK—enter newly written topic into google doc beyond class time

Independent Practice

Materials, Resources, & Physical Space

Reflection

Appendix F

Note. Julia’s section covered by an iZone staff member, Zoe Wisbey

Table 1

Planning for Pop-Up

| Timing | Content | Lead |

|---|---|---|

| 3:25-3:30 pm (5) | Welcome students to the iZone and provide context for what pops ups are (their purpose, how they function, how they’re different). | Kim, Sarah |

| 3:30-3:40 pm (10) |

Activity: warm up to YES, AND “When we’re getting ready to brainstorm, we need to put ourselves in a state of mind where we are open to wild ideas and where we are building off of one another’s unique perspectives/ideas. The #1 rule of brainstorming is: never say no (assume we’ll figure out a way to make it work) and build on the ideas of each other.” “Summer vacation trip.” Kim/Zoe (Problem: Connecting audience to research, with and without constraints) |

iZone staff |

| 3:40-3:55 pm (15) |

Activity: In 3 groups of 5, students will start at one whiteboard, each indicating a key element to pop-up design. Three whiteboards each with a different prompt:

“Using that ‘yes and’ mentality, we’re now going to brainstorm creative, out-of-the-box ideas for our pop-up event. When we ring the cowbell that means it’s time to rotate to the next whiteboard. Then, your job is to build on the ideas of the team that went before you.” Constraints:

8 minutes for first round; rotate 4 minutes for second round; rotate 2 minutes for third round |

iZone staff w/help from all |

Table 2

Prototyping: Research Transformation to Multimodal

| Timing | Content | Lead |

|---|---|---|

| 3:55-4 pm (5) |

Goal of next activities presented, PowerPoint with fill-in-the-blank: “OK, now we’re going to shift from thinking about the event itself to thinking about your own ideas for communicating your research. Before we start brainstorming, we each need to individually develop a challenge question/statement to help frame our brainstorming.” How might we create a multimodal experience or presentation that helps____your audience____ CONNECT with ____my research topic____? |

iZone staff |

| 4-4:15 pm (15) |

Students are introduced to five categories of multimodal expression

First round, students get to choose their “go to,” the category that speaks to them the most (whether by individual talent or logical connection with the research topic). Begin to develop a prototype. Students within the category are encouraged to brainstorm with each other. |

Kim |

| 4:15-4:25 pm (10) |

Second round, students choose a card from a basket that limits them to a new mode of expression (if they have already worked with this mode, they need to choose again). Begin to develop a prototype. Students within the category are encouraged to brainstorm with each other. |

Sarah |

Table 3

Sharing and Planning for Pop-Up

| Timing | Content | Lead |

|---|---|---|

| 4:25-4:30 pm (5) |

A few students share their ideas |

Sarah |

| 4:30-4:40 pm (10) |

We revisit the YES, AND planning for the pop-up. Now with some ideas of what the activities could look like in the pop-up (student research turned into multimodal expression), can we re-evaluate the Post-it notes to narrow down specifics of the pop-up? |

Kim |

A series of events where deans, faculty, and managers of various organizations are invited to talk about things they failed at, so as to embrace failures and encourage thinking of new ideas and solutions to problems.