Identify: Understanding Your Information Need

In this chapter, you will learn about the first pillar of information literacy. While the pillars are normally presented in a certain order, it is important to remember that they are not intended to be a step-by-step guide to be followed in a strict order. In most research projects, you will find that you move back and forth between the different pillars as you discover more information and come up with more questions about your topic. In this chapter you will learn how to identify your information need so that you can begin your research, but it is likely that you will also revisit some of the ideas in this chapter to make sure you are actually meeting that need with your research findings.

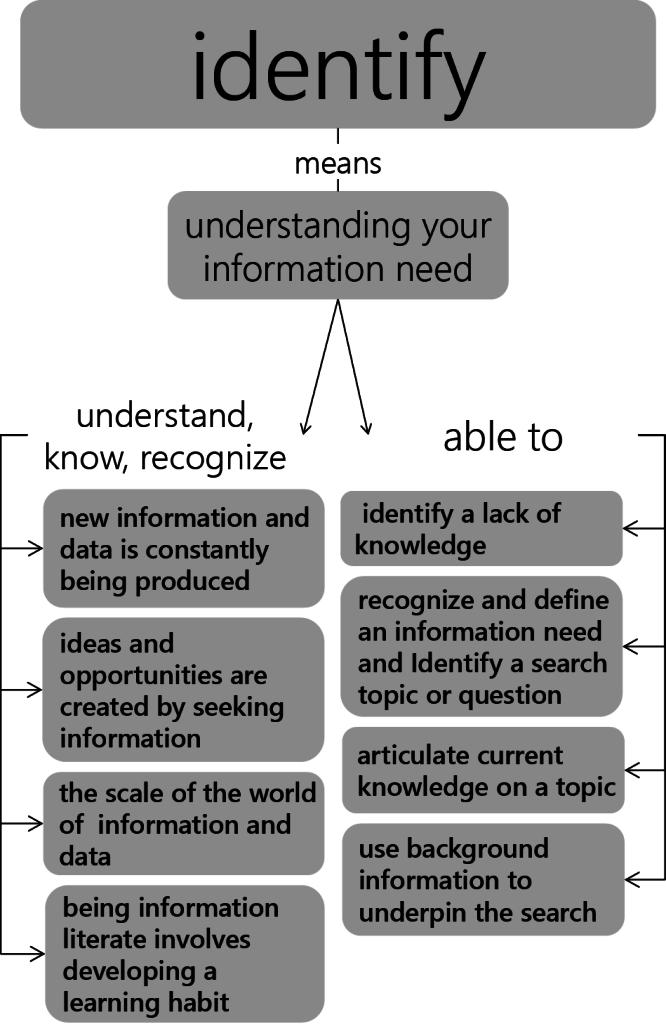

A person proficient in the Identify pillar is expected to be able to identify a personal need for information. They understand

- That new information and data is constantly being produced and that there is always more to learn

- That being information literate involves developing a learning habit so new information is being actively sought all the time

- That ideas and opportunities are created by investigating/seeking information

- The scale of the world of published and unpublished information and data

They are able to

- Identify a lack of knowledge in a subject area

- Identify a search topic/question and define it using simple terminology

- Articulate current knowledge on a topic

- Recognize a need for information and data to achieve a specific end and define limits to the information need

- Use background information to underpin the search

- Take personal responsibility for an information search

- Manage time effectively to complete a search

Scenario

Norm Allknow was having trouble. He had been using computers since he was five years old and thought he knew all there was to know about them. So, when he was given an assignment to write about the impact of the Internet on society, he thought it would be a breeze. He would just write what he knew, and in no time the paper would be finished. In fact, Norm thought the paper would probably be much longer than the required ten pages. He spent a few minutes imagining how impressed his teacher was going to be, and then sat down to start writing.

He wrote about how the Internet had helped him to play online games with his friends, and to keep in touch with distant relatives, and even to do some homework once in a while. Soon he leaned back in his chair and looked over what he had written. It was just half a page long and he was out of ideas.

Identifying a Personal Need for Information

One of the first things you need to do when beginning any information-based project is to identify your personal need for information. This may seem obvious, but it is something many of us take for granted. We may mistakenly assume, as Norm did in the above example, that we already know enough to proceed. Such an assumption can lead us to waste valuable time working with incomplete or outdated information. Information literacy addresses a number of abilities and concepts that can help us to determine exactly what our information needs are in various circumstances. These are discussed below, and are followed by exercises to help develop your fluency in this area.

Understanding the Context of an Information Need

When you realize that you have an information need it may be because you thought you knew more than you actually do, or it may be that there is simply new information you were not aware of. One of the most important things you can do when starting to research a topic is to scan the existing information landscape to find out what is already out there. We’ll get into more specific strategies for accessing different types of information later in the book, particularly in the Gather chapter, but for now it pays to think more broadly about the information environment in which you are operating.

For instance, any topic you need information about is constantly evolving as new information is added to what is known about the topic. Trained experts, informed amateurs, and opinionated laypeople are publishing in traditional and emerging formats; there is always something new to find out. The scale of information available varies according to topic, but in general it’s safe to say that there is more information accessible now than ever before.

Due to the extensive amount of information available, part of becoming more information literate is developing habits of mind and of practice that enable you to continually seek new information and to adapt your understanding of topics according to what you find. Because of the widely varying quality of new information, evaluation is also a key element of information literacy, and will be addressed in the Evaluate chapter of this book.

Finally, while you are busy searching for information on your current topic, be sure to keep your mind open for new avenues or angles of research that you haven’t yet considered. Often the information you found for your initial need will turn out to be the pathway to a rich vein of information that can serve as raw material for many subsequent projects.

When you understand the information environment where your information need is situated, you can begin to define the topic more clearly and you can begin to understand where your research fits in with related work that precedes it. Your information literacy skills will develop against this changing background as you use the same underlying principles to do research on a variety of topics.

From Information Need to Research Question

Norm was abruptly confronted by his lack of knowledge when he realized that he had nothing left to say on his topic after writing half a page. Now that he is aware of that shortcoming, he can take steps to rectify it.

Your own lack of knowledge may become apparent in other ways. When reading an article or textbook, you may notice that something the author refers to is completely new to you. You might realize while out walking that you can’t identify any of the trees around your house. You may be assigned a topic you have never heard of.

Exercise: Identifying What You Don’t Know

Wherever you are, look around you. Find one thing in your immediate field of view that you can’t explain.

What is it that you don’t understand about that thing?

What is it that you need to find out so that you can understand it?

How can you express what you need to find out?

For example: You can’t explain why your coat repels water. You know that it’s plastic, and that it’s designed to repel water, but can’t explain why this happens. You need to find out what kind of plastic the coat is made of and the chemistry or physics of that plastic and of water that makes the water run off instead of soaking through. (The terminology in your first explanation would get more specific once you did some research.)

All of us lack knowledge in countless areas, but this isn’t a bad thing. Once we step back and acknowledge that we don’t know something, it opens up the possibility that we can find out all sorts of interesting things, and that’s when the searching begins.

Taking your lack of knowledge and turning it into a search topic or research question starts with being able to state what your lack of knowledge is. Part of this is to state what you already know. It’s rare that you’ll start a search from absolute zero. Most of the time you’ve at least heard something about the topic, even if it is just a brief reference in a lecture or reading. Taking stock of what you already know can help you to identify any erroneous assumptions you might be making based on incomplete or biased information. If you think you know something, make sure you find at least a couple of reliable sources to confirm that knowledge before taking it for granted. Use the following exercise to see if there is anything that needs to be supported with background research before proceeding.

Exercise: Taking Stock of What you Already Know

As discussed above, part of identifying your own information need is giving yourself credit for what you already know about your topic. Construct a chart using the following format to list whatever you already know about the topic.

Name your topic at the top.

In the first column, list what you know about your topic.

In the second column, briefly explain how you know this (heard it from the professor, read it in the textbook, saw it on a blog, etc.).

In the last column, rate your confidence in that knowledge. Are you 100% sure of this bit of knowledge, or did you just hear it somewhere and assume it was right?

When you’ve looked at everything you think you know about the topic and why, step back and look at the chart as a whole. How much do you know about the topic, and how confident are you about it? You may be surprised at how little or how much you already know, but either way you will be aware of your own background on the topic. This self-awareness is key to becoming more information literate.

This exercise gives you a simple way to gauge your starting point, and may help you identify specific gaps in your knowledge of your topic that you will need to fill as you proceed with your research. It can also be useful to revisit the chart as you work on your project to see how far you’ve progressed, as well as to double check that you haven’t forgotten an area of weakness.

Once you’ve clearly stated what you do know, it should be easier to state what you don’t know. Keep in mind that you are not attempting to state everything you don’t know. You are only stating what you don’t know in terms of your current information need. This is where you define the limits of what you are searching for. These limits enable you to meet both size requirements and time deadlines for a project. If you state them clearly, they can help to keep you on track as you proceed with your research. You can learn more about this in the Scope chapter of this book.

One useful way to keep your research on track is with a “KWHL” chart. This type of chart enables you to state both what you know and what you want to know, as well as providing space where you can track your planning, searching and evaluation progress. For now, just fill out the first column, but start thinking about the gaps in your knowledge and how they might inform your research questions. You will learn more about developing these questions and the research activities that follow from them as you work through this book.

Defining a research question can be more difficult than it seems. Your initial questions may be too broad or too narrow. You may not be familiar with specialized terminology used in the field you are researching. You may not know if your question is worth investigating at all.

These problems can often be solved by a preliminary investigation of existing published information on the topic. As previously discussed, gaining a general understanding of the information environment helps you to situate your information need in the relevant context and can also make you aware of possible alternative directions for your research. On a more practical note, however, reading through some of the existing information can also provide you with commonly used terminology, which you can then use to state your own research question, as well as in searches for additional information. Don’t try to reinvent the wheel, but rely on the experts who have laid the groundwork for you to build upon.

Once you have identified your own lack of knowledge, investigated the existing information on the topic, and set some limits on your research based on your current information need, write out your research question or state your thesis. The next exercise will help you transform the question you have into an actual thesis statement. You’ll find that it’s not uncommon to revise your question or thesis statement several times in the course of a research project. As you become more and more knowledgeable about the topic, you will be able to state your ideas more clearly and precisely, until they almost perfectly reflect the information you have found.

Exercise: Research Question/Thesis Statement/Search Terms

Since this chapter is all about determining and expressing your information need, let’s follow up on thinking about that with a practical exercise. Follow these steps to get a better grasp of exactly what you are trying to find out, and to identify some initial search terms to get you started.

- Whatever project you are currently working on, there should be some question you are trying to answer. Write your current version of that question here.

- Now write your proposed answer to your question. This may be the first draft of your thesis statement which you will attempt to support with your research, or in some cases, the first draft of a hypothesis that you will go on to test experimentally. It doesn’t have to be perfect at this point, but based on your current understanding of your topic and what you expect or hope to find is the answer to the question you asked.

- Look at your question and your thesis/hypothesis, and make a list of the terms common to both lists (excluding “the,” “and,” “a,” etc.). These common terms are likely the important concepts that you will need to research to support your thesis/hypothesis. They may be the most useful search terms overall or they may only be a starting point.

If none of the terms from your question and thesis/hypothesis lists overlap at all, you might want to take a closer look and see if your thesis/hypothesis really answers your research question. If not, you may have arrived at your first opportunity for revision. Does your question really ask what you’re trying to find out? Does your proposed answer really answer that question? You may find that you need to change one or both, or to add something to one or both to really get at what you’re interested in. This is part of the process, and you will likely discover that as you gather more information about your topic, you will find other ways that you want to change your question or thesis to align with the facts, even if they are different from what you hoped.

A Wider View

While the identification of an information need is presented in this chapter as the first step in the research process, many times the information need you initially identified will change as you discover new information and connections. Other chapters in this book deal with finding, evaluating, and managing information in a variety of ways and formats. As you become more skilled in using different information resources, you will likely find that the line between the various information literacy skills becomes increasingly blurred, and that you will revisit your initial ideas about your topic in response to both the information you’re finding and what you’re doing with what that information.

Continually think about your relationship to the information you find. Why are you doing things the way you are? Is it really the best way for your current situation? What other options are there? Keeping an open mind about your use of information will help you to ensure that you take responsibility for the results of that use, and will help you to be more successful in any information-intensive endeavor.