Evaluate: Assessing Your Research Process and Findings

Introduction

In 2010, a textbook being used in fourth grade classrooms in Virginia became big news for all the wrong reasons. The book, Our Virginia by Joy Masoff, had caught the attention of a parent who was helping her child do her homework, according to an article in The Washington Post. Carol Sheriff was a historian for the College of William and Mary and as she worked with her daughter, she began to notice some glaring historical errors, not the least of which was a passage which described how thousands of African Americans fought for the South during the Civil War.

Further investigation into the book revealed that, although the author had written textbooks on a variety of subjects, she was not a trained historian. The research she had done to write Our Virginia, and in particular the information she included about Black Confederate soldiers, was done through the Internet and included sources created by groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization which promotes views of history that de-emphasize the role of slavery in the Civil War.

How did a book with errors like these come to be used as part of the curriculum and who was at fault? Was it Masoff for using untrustworthy sources for her research? Was it the editors who allowed the book to be published with these errors intact? Was it the school board for approving the book without more closely reviewing its accuracy?

There are a number of issues at play in the case of Our Virginia, but there’s no question that evaluating sources is an important part of the research process and doesn’t just apply to Internet sources. Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work. Being able to understand and apply the concepts that follow is crucial to becoming a more savvy user and creator of information.

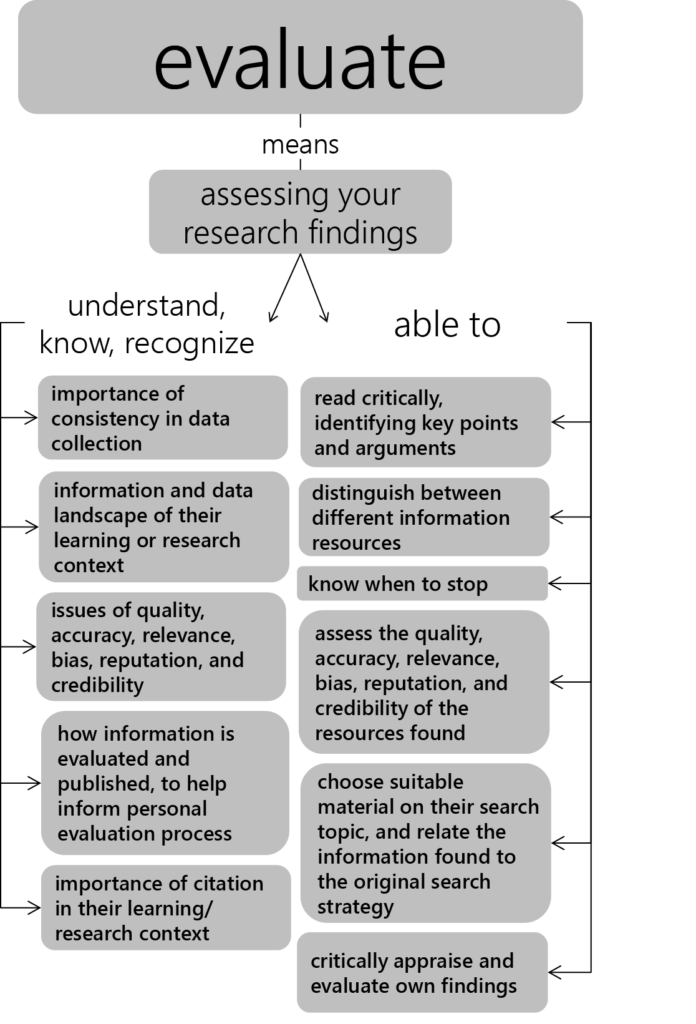

The Evaluate pillar states that individuals are able to review the research process and compare and evaluate information and data. It encompasses important knowledge and abilities.

They understand

- The information and data landscape of their learning/research context

- Issues of quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility relating to information and data sources

- How information is evaluated and published, to help inform their personal evaluation process

- The importance of consistency in data collection

- The importance of citation in their learning/research context

They are able to

- Distinguish between different information resources and the information they provide

- Choose suitable material on their search topic, using appropriate criteria

- Assess the quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility of the information resources found

- Assess the credibility of the data gathered

- Read critically, identifying key points and arguments

- Relate the information found to the original search strategy

- Critically appraise and evaluate their own findings and those of others

- Know when to stop

The first section of this chapter will talk about some of the ideas and concepts behind evaluating sources (the abilities in the above list), while the second section will give you the opportunity to put your evaluation skills into practice.

Distinguishing Between Information Resources

Information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to evaluation. Consider the following formats.

Social Media

Social media is a quickly rising star in the landscape of information gathering. Facebook updates, tweets, wikis, and blogs have made information creators of us all and have a strong influence not just on how we communicate with each other but also on how we learn about current events or discover items of interest. Anyone can create or contribute to social media and nothing that’s said is checked for accuracy before it’s posted for the world to see. So do people really use social media for research? Currently, the main use for social media like tweets and Facebook posts is as primary sources that are treated as the objects under study rather than sources of information on a topic. But now that the Modern Language Association has a recommended way to cite a tweet, social media may, in fact, be gaining credibility as a resource.

News Articles

These days, social media will generally be among the first to cover a big news story, with news media writing an article or report after more information has been gathered. News articles are written by journalists who either report on an event they have witnessed firsthand, or after making contact with those more directly involved. The focus is on information that is of immediate interest to the public and these articles are written in a way that a general audience will be able to understand. These articles go through a fact-checking process, but when a story is big and the goal is to inform readers of urgent or timely information, inaccuracies may occur. In research, news articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event.

Magazine Articles

While news articles and social media tend to concentrate on what happened, how it happened, who it happened to, and where it happened, magazine articles are more about understanding why something happened, usually with the benefit of at least a little hindsight. Writers of magazine articles also fall into the journalist category and rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Fact-checking in magazine articles tends to be more accurate because magazines publish less frequently than news outlets and have more time to get facts right. Depending on the focus of the magazine, articles may cover current events or just items of general interest to the intended audience. The language may be more emotional or dramatic than the factual tone of news articles, but the articles are written at a similar reading level so as to appeal to the widest audience possible. A magazine article is considered a popular source rather than a scholarly one, which gives it less weight in a research context but doesn’t take away the value completely.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts in a field and generally describe formal research studies or experiments conducted to provide new insight on a topic rather than reporting current events or items of general interest. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. This means that before an article is published, it undergoes a review process in order to confirm that the information is accurate and the research it discusses is valid. This process adds a level of credibility to the article that you would not find in a magazine or news article. Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is not easily understood by someone who does not already have some level of expertise on the topic. Though they may not be as easy to use, they carry a lot of weight in a research context, especially if you are working in a field related to science or technology. These sources will give you information to build on in your own original research.

Books

Books have been a staple of the research process since Gutenberg invented the printing press because a topic can be covered in more depth in a book than in most other types of sources. Also, the conventional wisdom for books is that anyone can write one, but only the best ones get published. This is becoming less true as books are published in a wider variety of formats and via a wider variety of venues than in previous eras, which is something to be aware of when using a book for research purposes. For now, the editing process for formally published books is still in place and research in the humanities, which includes topics such as literature and history, continues to be published primarily in this format.

Choosing Materials

When choosing a source for your research, what criteria do you usually use? Gauging whether the source relates to your topic at all is probably one. How high up it appears on the results list when you search may be another. Beyond that, you may base your decision at least partly on how easy it is to access.

These are all important criteria, to varying degrees, but there are other criteria you may want to keep in mind when deciding if a source will be useful to your research.

Quality

Scholarly journals and books are traditionally considered to be higher quality information sources because they have gone through a more thorough editing process that ensures the quality of their content. Generally, you also pay more to access these sources or may have to rely on a library or university to pay for access for you. Information on the Internet can also be of a high quality but there is less of a quality assurance process in place for much of that information. In the current climate, the highest quality information even on the Internet often requires a subscription or other form of payment for access.

Clues to a source’s level of quality are closely related to thinking about how the source was produced, including what format it was published in and whether it is likely to have gone through a formal editing process prior to publication.

Accuracy

A source is accurate if the information it contains is correct. Sometimes it’s easy to tell when a piece of information is simply wrong, especially if you have some prior knowledge of the subject. But if you’re less familiar with the subject, inaccuracies can be harder to detect, especially when they come in subtler forms such as exaggerations or inconsistencies.

To determine whether a source is accurate, you need to look more deeply at the content of the source, including where the information in the source comes from and what evidence the author uses to support their views and conclusions. It also helps to compare your source against another source. A reader of Our Virginia may not have reason to believe the information the author cites from the Sons of Confederate Veterans website is inaccurate, but if they compared the book against another source, the inconsistencies might become more apparent.

Relevance

Relevance has to do with deciding whether the source actually relates to your topic and, if it does, how closely it relates. Some sources may be an exact match; for others, you may need to consider a particular angle or context before you can tell whether the source applies to your topic. When searching for relevant sources, you should keep an open mind—but not too open. Don’t pick something that’s not really related just because it’s on the first page or two of results or because it sounds good.

You can assess the relevance of a source by comparing it against your research topic or research question. Keep in mind that the source may not need to match on all points, but it should match on enough points to be usable for your research beyond simply satisfying a requirement for an assignment.

Bias

An example of bias is when someone expresses a view that is one-sided without much consideration for information that might negate what they believe. Bias is most prevalent in sources that cover controversial issues where the author may attempt to persuade their readers to one side of the issue without giving fair consideration to the other side of things. If the research topic you are using has ever been the cause of heated debate, you will need to be especially watchful for any bias in the sources you find.

Bias can be difficult to detect, particularly when we are looking at persuasive sources that we want to agree with. If you want to believe something is true, chances are you’ll side with your own internal bias without consideration for whether a source exhibits bias. When deciding whether there is bias in a source, look for dramatic language and images, poorly supported evidence against an opposing viewpoint, or a strong leaning in one direction.

Reputation

Is the author of the source you have found a professor at a university or a self-published blogger? If the author is a professor, are they respected in their field or is their work heavily challenged? What about the publication itself? Is it held in high regard or relatively unknown? Digging a little deeper to find out what you can about the reputation of both the author and the publication can go a long way toward deciding whether a source is valuable.

You can investigate the reputation of an author by looking at any biographical information that is available as part of the source. Looking to see what else the author has published and whether this information has positive reviews is also important in establishing whether the author has a good reputation. The reputation of a publication can also be investigated through reviews, word-of-mouth by professionals in the field, or online databases that keep track of statistics related to a journal’s credibility.

Credibility

Credibility has to do with the believability or trustworthiness of a source based on evidence such as information about the author, the reputation of the publication, and how well-formatted the source is. How likely would you be to use a source that was written by someone with no expertise on a topic or a source that appeared in a publication that was known for featuring low quality information? What if the source was riddled with spelling and formatting errors? Looking at sources like these should inspire more caution.

Objectively, credibility can be determined by taking into account all of the other criteria discussed for evaluating a source. Knowing that some types of sources, such as scholarly journals, are generally considered more credible than others, such as self-published websites, may also help. Subjectively, deciding whether a source is credible may come down to a gut feeling. If something about a source doesn’t sit well with you, you may decide to pass it over.

Identifying Key Points and Arguments

Evaluating information about the source from its title, author, and summary information is only the first step. The evaluation process continues when you begin to read the source in more detail and make decisions about how (or whether) you will ultimately use it for your own research.

When you begin to look more deeply at your source, pay close attention to the following features of a document.

Introduction

The purpose of the introduction to any piece that has one is to give information about what the reader can expect from the source as a whole. There are different types of introductions, including forewords and prefaces that may be written by the author of the book or by someone else with knowledge of the subject. Introductory sections can include background information on why the topic was chosen, background on the author’s interest in the topic, context pertaining to why the topic is important, or the lens through which the topic will be explored. Knowing this information before diving in to the body of the work will help you understand the author’s approach to the topic and how it might relate to the approach you are taking in your own research.

Table of Contents

Most of the time, if your source is a book or an entire website, it will be divided into sections that each cover a particular aspect of the overall topic. It may be necessary to read through all of these sections in order to get a “big picture” understanding of the information being discussed or it may be better to concentrate only on the areas that relate most closely to your own research. Looking over the table of contents or menu will help you decide whether you need the whole source or only pieces of it.

List of References

If the source you’re using is research-based, it should have a list of references that usually appear at the end of the document. Reviewing these references will give you a better idea of the kind of work the author put into their own research. Did they put as much work into evaluating their sources as you are? Can you tell from the citations if the sources used were credible? When were they published? Do they represent a fair balance of perspectives or do they all support a limited point of view? What information does the author use from these sources and in what way does he or she use that information? Use your own research skills to spy on the research habits of others to help you evaluate the source.

Evaluating Your Findings

In the case of Our Virginia, the author used a biased source as part of her research and the inaccurate information she got from that source affected the quality of her own work. Likewise, if anyone had used her book as part of their research, it would have set off a chain reaction, since whatever information they cited from Our Virginia would naturally have to be called into question, possibly diminishing the value of their own conclusions.

Evaluating the sources you use for quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, and credibility is a good first step in making sure this doesn’t happen, but have you ever thought about evaluating the sources used by your own sources? This takes extra time, but looking at the reference list, bibliography, or notes section of any source you use to gauge the quality of the research done by the author of that source can be an important extra step.

Knowing When to Stop

For some researchers, the process of searching for and evaluating sources is a highly enjoyable, rewarding part of doing research. For others, it’s a necessary evil on the way to constructing their own ideas and sharing their own conclusions. Whichever end of the spectrum you most closely identify with, here are a few ideas about the ever-important skill of knowing when to stop.

You’ve satisfied the requirements for the assignment and/or your curiosity on the topic

If you’re doing research as part of a course assignment, chances are you’ve been given a required number of sources. Novice researchers may find this number useful to understand how much research is considered appropriate for a particular topic. However, a common mistake is to focus more on the number of sources than on the quality of those sources. Meeting that magic number is great, but not if the sources used are low quality or otherwise inappropriate for the level of research being done.

You have a deadline looming

Nothing better inspires forward motion in a research project than having to meet a deadline, whether it’s set by a professor, an advisor, a publisher, or yourself. Time management skills are especially useful, but since research is a cyclical process that sometimes circles back on itself when you discover new knowledge or change direction, planning things out in minute detail may not work. Leaving yourself enough time to follow the twists and turns of the research and writing process goes a long way toward getting your work in when it’s expected.

You need to change your topic

You’ve been searching for information on your topic for a while now. Every search seems to come up empty or full of irrelevant information. You’ve brought your case to a research expert, like a librarian, who has given advice on how to adjust your search or how to find potential sources you may have previously dismissed. Still nothing. It could be that your topic is too specific or that it covers something that’s too new, like a current event that hasn’t made it far enough in the information cycle yet. Whatever the reason, if you’ve exhausted every available avenue and there truly is no information on your topic of interest, this may be a sign that you need to stop what you’re doing and change your topic.

You’re getting overwhelmed

The opposite of not finding enough information on your topic is finding too much. You want to collect it all, read through it all, and evaluate it all to make sure you have exactly what you need. But now you’re running out of room on your flash drive, your Dropbox account is getting full, and you don’t know how you’re going to sort through it all and look for more. The solution: stop looking. Go through what you have. If you find what you need in what you already have, great! If not, you can always keep looking. You don’t need to find everything in the first pass. There is plenty of opportunity to do more if more is needed!

From Theory to Practice

Looking back, the Our Virginia case is more complicated than it may have first appeared. It wasn’t just that the author based her writing on research done through the Internet. It was the nature of the sources she used and the effect using those sources ultimately had on the quality of her own work. These mistakes happened despite a formal editing process that should have ensured better accuracy and an approval process by the school board that should have evaluated the material more closely. With both of these processes having failed, it was up to one of the book’s readers, the parent of a student who compared the information against her own specialized knowledge, to figure it all out.

Now that you know more about the theory behind evaluating sources, it’s time to apply the theory. The following section will help you put source evaluation into perspective using something called the CRAAP test. You’ll also have the opportunity to try out your new skills with several hands-on activities.

Evaluating Resources in Practice

When you begin evaluating sources, what should you consider? The CRAAP test is a series of common evaluative elements you can use. The CRAAP test was developed by librarians at California State University at Chico and it gives you a good, overall set of elements to look for when evaluating a resource. Let’s consider what each of these evaluative elements means.

Currency

One of the most important and interesting steps to take as you begin researching a subject is selecting the resources that will help you build your thesis and support your assertions. Certain topics require you to pay special attention to how current your resource is—because they are time sensitive, because they have evolved so much over the years, or because new research comes out on the topic so frequently. When evaluating the currency of an article, consider the following

- When was the item written, and how frequently does the publication it is in come out?

- Is there evidence of newly added or updated information in the item?

- If the information is dated, is it still suitable for your topic?

- How frequently does information change about your topic?

Exercise: Assess Currency

Assessing currency means understanding the importance of timely information

Imagine that you are writing a paper for a Political Science class on Japan’s environmental policy since the Kyoto Treaty. Identify one resource that you would find helpful in your research, and one resource that you would find less helpful. Write one sentence explaining why you would or would not use each resource, paying special attention to the currency of each item.

Relevance

Understanding what resources are most applicable to your subject and why they are applicable can help you focus and refine your thesis. Many topics are broad and searching for information on them produces a wide range of resources. Narrowing your topic and focusing on resources specific to your needs can help reduce the piles of information and help you focus in on what is truly important to read and reference. When determining relevance consider the following:

- Does the item contain information relevant to your argument or thesis?

- Read the article’s introduction, thesis, and conclusion.

- Scan main headings and identify article keywords.

- For book resources, start with the index or table of contents—how wide a scope does the item have? Will you use part or all of this resource?

- Does the information presented support or refute your ideas?

- If the information refutes your ideas, how will this change your argument?

- Does the material provide you with current information?

- What is the material’s intended audience?

Exercise: Find Relevant Sources

Relevance is the importance of the information for your specific needs

You are researching a paper where you argue that vaccinations have no connection to autism. Which of these resources would you consider relevant? Why or why not?

Hviid, Anders, Michael Stellfield, Jan Wohlfart, and Mads Melbye. “Association Between Thimerosal-Containing Vaccine and Autism.” Journal of the American Medical Association 290, no. 13 (October 1, 2003): 1763–1766. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=197365

Chepkemoi Maina, Lillian, Simon Karanja, and Janeth Kombich. “Immunization Coverage and Its Determinants among Children Aged 12–23 Months in a Peri-Urban Area of Kenya.” Pan-African Medical Journal 14, no.3 (February 1, 2013). http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/14/3/full/

Authority

Understanding more about your information’s source helps you determine when, how, and where to use that information. Is your author an expert on the subject? Do they have some personal stake in the argument they are making? What is the author or information producer’s background? When determining the authority of your source, consider the following

- What are the author’s credentials?

- What is the author’s level of education, experience, and/or occupation?

- What qualifies the author to write about this topic?

- What affiliations does the author have? Could these affiliations affect their position?

- What organization or body published the information? Is it authoritative? Does it have an explicit position or bias?

Exercise: Identify Authoritative Sources

Authority is the source of the information—the author’s purpose and what their credentials and/or affiliations are.

The following items are all related to a research paper on women in the workplace. Write two sentences for each resource explaining why the author or authors might or might not be considered authoritative in this field:

Carvajal, Doreen. “The Codes That Need to Be Broken.” New York Times, January 26, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/27/world/27iht-rules27.html?_r=0

Sheffield, Rachel. “Breadwinner Mothers: The Rest of the Story.” The Foundry Conservative Policy News Blog, June 3, 2013. http://blog.heritage.org/2013/06/03/breadwinner-mothers-the-rest-of-the-story

Baker, Katie J.M. “Your Guide to the Very Important Paycheck Fairness Act.” Jezebel (blog), January 31, 2013, http://jezebel.com/5980513/your-handy-guide-to-the-very-important-paycheck-fairness-act

Accuracy

Determining where information comes from, if evidence supports the information, and if the information has been reviewed or refereed can help you decide how and whether to use a source. When determining the accuracy of a source, consider the following:

- Is the source well-documented? Does it include footnotes, citations or a bibliography?

- Is information in the source presented as fact, opinion or propaganda? Are biases clear?

- Can you verify information from referenced information in the source?

- Is the information written clearly and free of typographical and grammatical mistakes? Does the source look to be edited before publication? A clean, well-presented paper does not always indicate accuracy, but usually at least means more eyes have been on the information.

Exercise: Find Accurate Sources

Accuracy is the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

Which of the following articles are peer reviewed? How do you know? How did you find out? Were you able to access the articles to examine them?

- Coleman, Isobel. “The Global Glass Ceiling.” Current 524 (2010): 3–6.

- Lang, Ilene H. “Have Women Shattered the Glass Ceiling?” Editorial, USA Today, April 14, 2010, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/forum/2010-04-15-column15_ST1_N.htm?csp=34

- Townsend, Bickley. “Breaking Through: The Glass Ceiling Revisited.” Equal Opportunities International 16, no. 5 (1997): 4–13.

Purpose

Knowing why information was created is a key to evaluation. Understanding the reason or purpose of the information, if the information has clear intentions, or if the information is fact, opinion or propaganda will help you decide how and why to use information

- Is the author’s purpose to inform, sell, persuade, or entertain?

- Does the source have an obvious bias or prejudice?

- Is the article presented from multiple points of view?

- Does the author omit important facts or data that might disprove their argument?

- Is the author’s language informal, joking, emotional, or impassioned?

- Is the information clearly supported by evidence?

Exercise: Identify the Information Purpose

Purpose is the reason the information exists—determine if the information has clear intentions or purpose and if the information is fact, opinion, or propaganda.

Take a look at the following sources. Why do you think this information was created? Who is the creator?

- http://www.chevron.com/globalissues/climatechange/

- http://www.beefnutrition.org/

- Fahrenheit 911—Movie. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0361596/

- Lydall, Wendy. Raising a Vaccine Free Child. Inkwazi Press, 2009

- http://www.nwf.org/What-We-Do/Protect-Habitat/Gulf-Restoration/Oil-Spill/Effects-on-Wildlife.aspx

- http://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/

- Owen, Mark and Kevin Maurer. No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission That Killed Osama Bin Laden. New York: Penguin, 2012.

- Your Brain on Video Games http://www.ted.com/talks/daphne_bavelier_your_brain_on_video_games.html

Conclusion

When you feel overwhelmed by the information you are finding, the CRAAP test can help you determine which information is the most useful to your research topic. How you respond to what you find out using the CRAAP test will depend on your topic. Maybe you want to use two overtly biased resources to inform an overview of typical arguments in a particular field. Perhaps your topic is historical and currency means the past hundred years rather than the past one or two years. Use the CRAAP test, be knowledgeable about your topic, and you will be on your way to evaluating information efficiently and well!