Visual Literacy: Applying Information Literacy to Visual Materials

Scenario

Louis was recently hired as an office assistant for an advertising firm. His first project is to create a presentation to describe the firm’s services to potential clients. His boss specified that it should be as visual as possible and be designed for a large projector screen. If the firm likes the work, it will be adapted into both a website and a printed pamphlet. Louis has some experience with creating PowerPoint presentations for school and has used Pinterest and other image-related tools, so he figures this will be a piece of cake.

Introduction

This chapter is different from most of the others in this textbook, in that it does not focus on one particular aspect or pillar of information literacy. Instead, it looks at a specific area of information literacy: visual literacy. So, while each of the previous chapters looked closely at only one pillar, this chapter will look at each pillar as it relates to the field of visual literacy.

Visual literacy has never been more critical. The Association of College and Research Libraries states,

The importance of images and visual media in contemporary culture is changing what it means to be literate in the 21st century. Today’s society is highly visual, and visual imagery is no longer supplemental to other forms of information. New digital technologies have made it possible for almost anyone to create and share visual media. Yet the pervasiveness of images and visual media does not necessarily mean that individuals are able to critically view, use, and produce visual content. Individuals must develop these essential skills in order to engage capably in a visually-oriented society. Visual literacy empowers individuals to participate fully in a visual culture.[1]

Currently, most models of information literacy do not include visual literacy elements. Emerging models such as transliteracy and metaliteracy do incorporate aspects of visual literacy, but these models have not yet become mainstream information literacy approaches. Because of this gap, the authors of this textbook agreed on the need for a separate chapter dedicated to the subject.

A note on the lack of images in this chapter: You may find it surprising that the chapter about visual communication has very few pictures. This has to do with the high level of copyright restriction for publishing images; unlike text, one cannot quote a visual work and simply cite it without permission (more on this later). We requested consent to use several of the images referenced in this chapter, but at the time of publication, the permissions were not yet granted. The images we do use are within the public domain, and links and references have been provided for others so that you can view the images’ external sources.

Definition of Visual Literacy

Visual literacy is the ability to identify, gather, evaluate, manage, use, create, and share visual material in an effective, ethical, and self-aware manner. Over the years, individual disciplines have created widely varying definitions that emphasize only one particular aspect of visual literacy. This chapter aims to take the broadest possible view, using an inclusive definition that can be applied to any field.

Brief History of the Term

The history of visual communication goes back to the cave paintings 30,000 years ago; the description of it only 2,500 years. . . . Visual literacy is 2,500 years old (as a skill) and 30 years young (as a term).[2]

The idea of visual literacy is not new. Using images to communicate precedes the use of text by many thousands of years. Discussions about the concept of visual language have been around for quite a while as well. Perhaps most famously, Sir Francis Bacon discussed visual literacy in the 1600s.[3] Subsequent scholars in areas ranging from art history and appreciation to philosophy and psychology have continued to grapple with the concept. The field of photography has a long relationship with visual literacy. Henry Holmes Smith, an author and professor of photography at Indiana University in the 1950s, is credited with coining the term visual literacy.[4] Smith described it as “a visual language, one that probably cannot be taught until it is codified. . . . I can hardly wait to read some general principles on picture reading.”[5]

Several years later, in 1969, a group of scholars and artists from a wide range of disciplines founded the International Visual Literacy Association, bringing the concept and the term into the mainstream. IVLA continues to be the standard bearer for visual literacy, publishing a journal and sponsoring an annual international conference.

Value of Visual Literacy

If students aren’t taught the language of sound and images, shouldn’t they be considered as illiterate as if they left college without being able to read or write?

—George Lucas[6]

We live in an increasingly visual society. Since the creation of the computer desktop icon, there has been an exponential shift toward communicating with images. Whether for research, employment, or social interaction, visual literacy has never been more important. It is especially critical in the workplace, and will only become more so. Increased visual literacy also makes us smarter! Studies have shown that becoming more visually literate leads to greater overall intelligence and is correlated to greater performance in technical areas.[7]

Use of images has advantages for communication as well. One study found that humans process visual images several thousand times faster than text,[8] while other research has shown that information conveyed with images is more intuitively understood and better recalled.[9] Visual literacy is also unusual in its ability to span cultures and languages in a way that text does not.[10] It is also remarkably conducive to metacognition. Literary theorist John Zuern states,

Visual materials engage us in a dialogue with those ideas out of which we gain an understanding based less on memorization and mastery than on critical, intellectually supple inquiry. Moreover, visualization can spark invaluable ‘ah-ha’ experiences that push learners’ understanding of concepts beyond an instrumental ‘application’ of ideas in a particular discipline . . . and open them to philosophical reflection on their own social, cultural, and political lives.[11]

A well-known example of this is the photograph, Flower Power, taken by Bernie Boston in 1967. This is the famous image of a Vietnam War protester placing a flower in the barrel of a rifle held by a soldier. For many, this photograph came to symbolize the national divide between those who were for and against the war, in ways that no amount of words could.[12] Many feel that the increase of photojournalism during this era was a significant catalyst in changing public opinion and speeding the United States’ withdrawal from Vietnam.[13]

Visual Communication Challenges

Many think, as Louis first does, that we are all naturally skilled in visual literacy. But visual communication is in fact more difficult to learn and use than text. Part of this difficulty is related to the subtleties of visual communication. Whereas we know whether we can read a given word, it is easy to unwittingly misread an image. It is also much harder to copy or create images than letters.[14] Using visual imagery to communicate a specific message is not simply a matter of a clear substitution of images for words, but is instead a complex process with no agreed-upon rules. Standards of image use and interpretation vary by discipline and there is no singular alphabet or grammar.[15] So, becoming visually literate involves not only learning how to find and use images but also understanding the range of meanings they may have in different contexts.[16]

With this in mind, let’s check in to see how Louis is doing.

At first things went smoothly. Louis created a basic presentation and then looked online for pictures to add. He found many websites that had most of the images he was looking for and he was able to copy and paste from these sites into his presentation. But now he is having some trouble. For one thing, some of the images don’t look great when he zooms in, and he is worried about projecting them. Also, he would like to be able to change some of the images by adjusting brightness and colors and, for one, he wants to take out the background. Finally, he feels that the presentation is still pretty boring: there are a lot of facts and figures to share, and the slides are filled with lists and tables of data. He is sure there are tools to improve all of these issues, and probably places to look for examples, but he doesn’t know where to start.

Applying the Seven Pillars

Identify

This pillar focuses on understanding one’s information needs so that a research question or goal can be formulated. What does this look like when applied to visual literacy? Let’s start with Louis. He needs visual materials for a business presentation. This sounds simple, but there are many important details that he did not stop to consider. He needs to consider the audience: what is their culture? Is there a specific dialect of images—certain logos or symbols that have special meaning? Are there images to avoid because of their particular meaning either within the company or the broader industry? The intent is also important. In this case, the purpose is both to inform and persuade; each will influence which images are chosen and how they are used. There are also technical aspects: the presentation will be given in multiple formats, each with its own set of best practices and considerations. This includes ethical and legal aspects, which vary depending on the purpose and venue, and should especially be considered for any commercial use of images.

Based on these factors, Louis’ research goal seems to be: find images in a variety of formats and resolutions that he can legally use for both in-house and public marketing. In general, tools for this stage can include subject manuals and magazines, websites of peer organizations, previous publications created by the institution one is working for, as well as relevant physical spaces. For Louis, it would make sense to look at the company website and all other materials, any previous presentations used, the product itself, the company offices (including architecture and even dress codes), as well as competitors’ work.

Scope

This pillar centers on knowing your own knowledge and gaps, and being aware of what information is available. For visual literacy, this starts with your current ability to find and create images, and your awareness of what tools are available for these tasks. Finding and creating aren’t just digital skills, but can include looking through magazines and books, creating collages, taking photographs, drawing, and more. Knowledge of available resources includes knowing where to discover more material, a process greatly aided by knowing your own gaps in knowledge and experience. In Louis’ case, he knows that he does not have photo editing skills. This knowledge will help him direct and focus his search: he needs to either find images that don’t need adjusting or he has to find and learn how to use photo editing tools. The awareness that images can be altered is also a critical aspect of the scope of visual literacy. Besides knowledge of tools, it is critical to know what types of images exist, what their particular qualities are, and how these influence usability and accessibility. Specific examples include photographs, paintings, videos, cartoons, and icons, to name a few. Also, one should discover existing formats and their differences and advantages. There are numerous physical and digital formats each with distinct and important differences in resolution, size, adaptability, and accessibility.[17]

Many resources are available to assist with this stage of the process. There are countless physical and digital image repositories, including libraries, museums, galleries, and websites such as Picasa, Flickr, Pinterest, and many more. And, there are just as many tools for manipulating visual materials, including paint, scissors, scanners, software such as Photoshop, and several excellent programs that can be used online or downloaded for free. It is also possible to find classes offering help in using these tools, frequently offered by area schools, libraries, or community centers.

Exercise: Observing the Visual Landscape

Go to Google Images and study the results for searches using each of these terms:

professor

librarian

baby

Now, reflect upon what you found:

- What patterns did you notice?

- What assumptions underlie, or are promoted by, these images?

- How do you think Google Images finds the pictures?

Plan

This pillar involves choosing the best search tools and developing effective search strategies. Plan is closely related to the Gather pillar described next: you will find yourself going back and forth between these two pillars in the course of your research. In the gathering stage, as you enact the strategies you formulated in the planning stage, you will naturally find yourself revising your strategies and creating new plans. In this chapter, we will focus on the thinking components of Plan and the action elements of Gather. For Plan, concerns specific to visual literacy begin with knowing where to look for various types of visual materials. In addition to the previously mentioned sites, there are excellent dedicated image collections available through the Library of Congress, New York Public Library, and ARTstor (which requires a subscription). It is important to keep in mind that most of these images are NOT copyright free; they cannot be freely used for some purposes without permission. Several online resources do exist for images that are free to use (with attribution), even for commercial purposes. Some standouts include Stockfreeimages, Openphoto, Imageafter, as well as Pixelperfectdigital and Morguefile, which all have excellent advanced search options. Flickr also offers an advanced search that has the added feature of allowing you to view only images with Creative Commons licenses supporting reuse. For classical art, two good online resources are Art Resource (which displays artworks from hundreds of museums around the world) and Web Gallery of Art (notable for its many high-resolution images).

Image searching can be challenging because subject terms for images have not been standardized. Most sites don’t offer advanced searching, leaving it up to the researcher to find the best strategies. What works best for one repository often does not suit another, so part of this stage involves learning the internal logic of each resource. Thankfully, there are some techniques that allow for searching across several sites. Conducting a Google image search is currently the best method, due to Google’s excellent advanced search option that allows for limiting by size, format, usage rights, and more. Google also allows you to search using an image as your search term, which can be terrifically helpful since it bypasses the problem of variations in words used to describe images. This is a perfect example of visual literacy: using one image to describe another image! This method can also be used to find information about an image you have, such as the species of a bird you photographed or the artist for a particular painting.[18]

Before we proceed, let’s check in again with Louis.

Louis has decided to start fresh. He realizes that his project should focus on a clear goal, and that he wants to find images that clearly communicate his topic right from the beginning of his presentation—rather than adding them at the end as an afterthought. Knowing that he has limited experience in manipulating images, he attends a free Photoshop course taught at a local library. There, he learns some basic editing skills, as well as the differences between formats such as JPG and PNG, and what sizes and resolutions work best for different purposes. Armed with this new knowledge, Louis identifies several online image repositories that he plans to use. Once he finds the most appropriate images, he will download them and possibly alter some to better suit his needs. His next step is to start searching for and downloading images.

Gather

This pillar concentrates on using the strategies outlined in the planning stage to locate and access information. This is a particularly challenging process for visual literacy, although it may initially seem easy. While a vast amount of visual material is available online, and some good tools for finding it exist (as identified in Scope), conducting specific searches is quite difficult. Finding a precise image often requires hours of trial and error, and exploring multiple resources, and even when advanced searching is possible it may not yield the desired results. Often, descriptions for images are user-generated tags that lack consistency (even within a repository) and that change over time as new tags are added. This means that determining accuracy is quite difficult: is that actually a picture of Karl Marx, or is it Santa Claus as one tag says? Finding specific formats and resolutions is similarly challenging. For one, most images freely available online are not of high enough resolution or proper formats to be used for publications or large projections. And finding those that are is difficult because of inconsistencies in terminology. A few representative examples: JPG and JPEG are both used to describe the same format, while dpi and ppi are not the same but are often used interchangeably—and these are some of the most-used formats and considerations for digital images!

Accessing images is equally challenging, at multiple levels. There is a wide range of the level of accessibility for visual materials, from watermark-protected images for sale (and often requiring signup to access) to high-resolution images that are easily accessed and legally free for all to use (quite rare). Often, the difference between the two is not immediately apparent: pop-up screens demanding payment often appear only once you have searched for and selected an image that you want to use. Now, reading the previous sentences, you may have thought, “But I get images easily all the time! Flickr, Pinterest, Google Images: just Right-Click and it’s yours!” This brings us to the other key aspect of online image accessibility: copyright. While it is true that one can often easily and instantly download an image, this is almost always in violation of copyright. From an earlier example: if you search online for Flower Power Bernie Boston, you will find links to hundreds of webpages posting this photograph. Most of these sites are doing so illegally, without permission of the copyright holder, which in this case is the Worcester Art Museum. Many websites seem specifically designed for open use, such as Pinterest, but nearly all of the postings are illegal while being firmly within the site’s stated intent.[19] For images, it is often up to the researcher to make sure he or she is on ethical and legal solid ground. We will discuss this further in the sections on managing and presenting.

For visual materials, another important aspect of access involves saving copies. Because you will often want to use an actual image, rather than merely quoting or referencing it as you might a text, it will be necessary to have a copy of the image to use. This could mean a photocopy, scan, tracing, hand drawing, photograph, or, more often, a digital reproduction. Besides knowing how to copy or save an image, it is important to have a detailed record of its source. This can help you find the original image again later and has other benefits we will discuss in the Gather and Present sections of this chapter. You will also need an accurate citation to include with the image in your final product.

Evaluate

This pillar focuses on the evaluation of information in an ongoing review of one’s research process. Key elements related to visual literacy include determining quality, bias, and accuracy, as these are all especially tricky to determine for visual materials.

Quality

Quality in this case refers both to the substantive value and the visual strength of an image. An example to demonstrate the difference between the two: a deer crossing sign is quickly and universally understood (high substantive value), but does not achieve its purpose if it is faded (low visual strength). Evaluating for substantive value is as important for visual materials as any other resource type and involves many of the same considerations, including looking critically at key elements and identifying subjects, relationships, context, and purpose (including intended audience). Visual strength is equally important and includes such qualities as brightness, clarity, contrast, hue, and saturation. These are important elements to consider both for evaluation and image creation. The size and format of an image also affect visual strength since what looks good in one venue may not in another; that wallet size photo of your sweetheart will probably be quite grainy if you make it into a poster. Some of these factors will be immediately apparent, as with the faded sign, but others require looking at the metadata for an image to determine file type, image size (which is not the same as the displayed size), resolution, and more. Legality is another key area of quality to assess. Who is allowed to use this image and for what purposes? There is a wide range of possible permissions and it is critical to determine whether your intended use is permitted. Many people have been sued—and fined or even jailed—for using images outside of a creator’s intent. If you cannot determine what type of image reuse is allowed, you are better off not using the image.

Bias

Bias can be particularly hard to identify for images. Often it is not the image itself but its context or description that displays a bias. Sometimes it is what is not shown that reveals bias, as when something is cropped or left out of the frame for a specific intent. Other times the very fact of an image being used is revealing, as when the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten printed caricatures of Mohammed despite knowing this would be offensive to many Muslims. (In a remarkable added twist that highlights the many layers of visual literacy, when Yale University published a book about this incident it chose not to include any of the images.)[20]

Accuracy

Accuracy is especially important to consider when evaluating images, since they can be easily altered in ways quite difficult to detect and are also often incorrectly described. The first step in assessing for accuracy involves looking carefully to see whether an image is believable and whether the captions seem to match the contents. One should consider both internal consistency (Does it look right, without strange shadows or edges or elements that seem off?) and external probability (Is this depicting a plausible thing or event?). Look for areas that appear too perfect or appear to be exact replicas of another area; tool marks left by software such as an unnaturally straight line, or a sudden break in color. As with any resource, consider the source: who published the image and why? It is also important to examine the metadata, ranging from the written caption to the digital information hidden within the image. Is this information consistent with the image, are the dates and descriptions correct? If the image is not original and is being reused, is it properly cited? A warning sign that an image is not a reliable resource is when there is no citation but the visual material is clearly from some other source.

All evaluation should be done in relation to your research goal: the most critical concern should be whether an item fits in the project context. Evaluation can inform your research process, with the search both responding to and suggesting adjustments to the original research question or desired product. Similarly, it is important to critically appraise your own role in the process, looking for your own biases or habits that could limit results. Comparing your perceptions with others through discussion and mutual review can also be very revealing.

Exercise: Accuracy and Bias

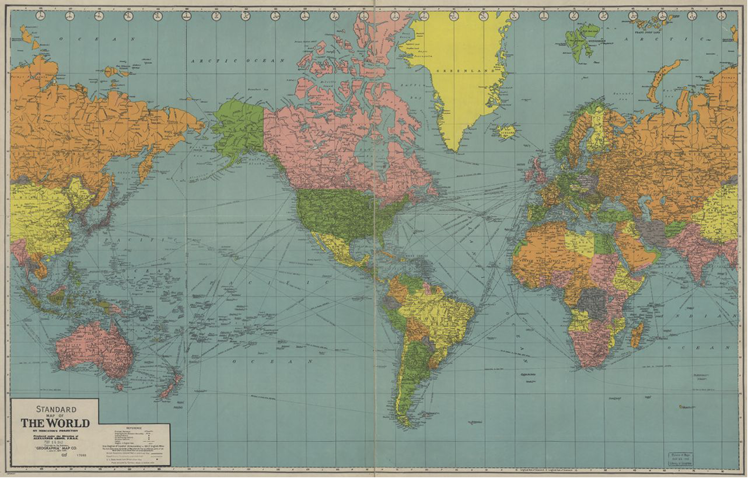

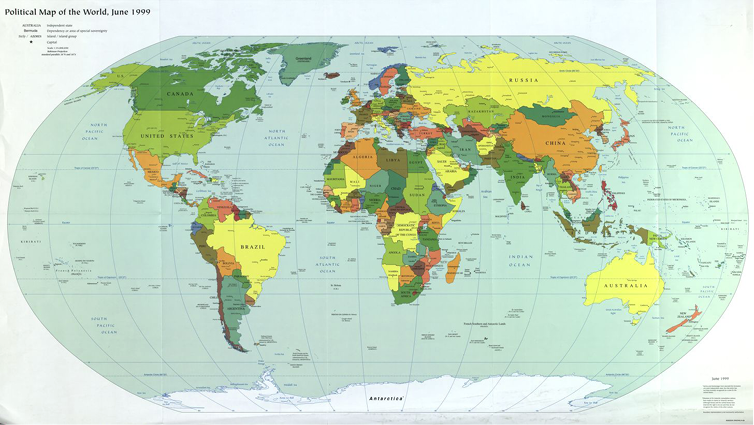

Look closely at the following maps: what differences do you see?

Now, compare these maps to a current globe.

- Are all three equally accurate?

- What implied messages could be interpreted by some of the visualization choices made?

- The map on top is from 1942, and the bottom map is from 1999, both printed in the United States. How might these facts be reflected in the layout of each map?

Manage

This pillar relates to information management—organizing your findings to aid comprehension, preservation, and retrieval. As with any other area of information literacy, for visual literacy information management begins with collecting your materials. We discussed the importance of recording source information when copying or saving; at this stage you will want to make sure that information stays linked to the correct image. There are a number of ways to do this, ranging from including it in the file name (e.g., AnselAdamsYosemite.jpg) to simply pasting the image and its identifying information in a word document. Many image processing programs will allow you to embed this information within the image itself. Whatever method you use, it is essential to do so in a consistent manner to support effective organization. It is also very helpful to name images in descriptive and clear ways that distinguish them, such as YellowLightningBoltBlackBgrnd.png. Additionally, you may want to create folders for different subjects or image types.

Citation

Citation for visual materials can be tricky, but it is critical for both managing and presenting your findings. Using an established citation format facilitates organization of images both within a publication and also for your own use. It also maintains a connection of the source information to the image, which will be important when you want to use or reference the image later. It is important to be able to create a bibliography in at least one citation format, since both professors and publishers will require you to document your sources. There are several programs that work for textual and visual materials, to assist you with this process, as well as print and online guides specifically for image citation (one is linked in the Additional Resources list).

Another management tool that can be very useful is keeping a research journal or similar record of your process. Documenting where and how you sought information (including specific search terms and strategies) and what you found can be very helpful. A research journal can help you with future searching and also supports sharing your process and helping others with their research. Many of the best tools available today were created from a previous searcher recording and sharing their experience: there is nothing stopping you from contributing! Doing so also brings you into conversation with other scholars who can help you substantially improve your work.

Now let’s look again at what Louis is up to.

Because his work will be used commercially, Louis narrowed his search to only sites supporting this type of use. He performed focused searches for specific images, making sure they had high enough resolutions for large projection and could legally be reused commercially. He carefully evaluated each image for relevance to his project, and for accuracy, and originality. One image looked familiar, so he used it to do a reverse image search that revealed that the Flickr user who posted it was not, in fact, the image creator. The image was not free to use, so he wisely chose to exclude it from his presentation. He kept a running log of his process and recorded citations for each image that he collected. He also pasted a copy of each image into a Word document. He then made folders for different types of images and sorted the files in them by format type. He now has a searchable pool of images to use in creating his presentation.

Present

This pillar focuses on summarizing, synthesizing, and communicating your work to others. This is the pillar with the widest range of connections to visual literacy. Many books have been dedicated to this topic alone. In this chapter we will highlight the central aspects of Present, and share some methods and tools you can use. As mentioned in the Present chapter, a fundamental aspect of this pillar is recognizing that we are all information creators. This is also true for visual communication, although we may not be as aware of our creator role in using visualized information. Have you ever used an emoticon? Created a doodle? Sent someone a photo you found online? Made a collage? All of these involve creation and imaginative reuse of images. These activities also require the ability to understand and communicate using visual language, which in many ways is the essence of visual literacy.[21] Now let’s look at the basic components of Present.

Summarizing & Synthesizing

For visual materials, the line between summarizing and synthesizing is often blurred, because one often does both when presenting information visually. The act of visualization is itself a form of synthesis. It is important for you to be aware of what data came from where, and to note your own contributions, including your commentary (intended or not). It is very easy to forget a source and then fail to provide a citation, thinking all of the project is original work. You can also easily fail to recognize your own bias and believe your work is just an objective summary. For these reasons, we strongly recommended that you have others review your work and provide critical feedback before publication. Citations are also important for summarizing and synthesizing, because they will help with both remembering your sources and giving credit to the creators. However, as mentioned throughout this chapter, providing citations does not protect all or even most image reuse: always make sure to look carefully at the copyright information for any visual material.

Communicating

Communication begins with determining your purpose and then selecting images and presentation methods that best support your objectives. When you plan to use visual communication, it is helpful to work visually from the start and use tools designed for that purpose. Concept mapping is a widely used visualization method that involves drawing concepts and connections on paper (or a computer screen), which can be helpful in getting free of verbal/intellectual patterns and starting to think visually. In this process one often finds that a certain visual logic arises, an intuitive sense of arc and layout that guides what content is chosen and how it is used. This is an important stage, because it involves immersing yourself in the internal rules and logic of the world of images.[22] These activities should align with the final research goal and take into account the purpose of the project. The character of your intended audience should inform presentation style and type, image selection and size, and color schemes, as well as the tools and processes you use for editing images. For instance, while you might show large cartoon images zooming around a circus-themed background when presenting to young children, this likely would not be the best way to reach a worker’s union. An added consideration that is often neglected is when not to use images. While visual communication is powerful, using an image to make every point may not be the best strategy: imagine learning that your partner is breaking up with you via emoticon and I’m sure you will agree. In any case, many excellent tools exist for every stage of presentation, ranging from concept mapping tools such as Bubbl.us and Mindomo to a vast array of editing and presenting tools. Some notable examples include presentation software such as PowerPoint and Prezi; timeline generators Dipity and Tiki-Toki; online photo editors Microsoft Publisher, Photoshop, Pixlr, and Splashup; and flexible and dynamic word cloud generators Wordle and Tagxedo.

Data visualization, which involves creating graphical displays of information or infographics, is another important area of visual communication. Using graphical displays is not new, but with many designers shifting from presenting information in traditional graphs and number tables to more inventive depictions in which every aspect including shapes and colors add significance, data visualization has recently gained significant traction. Infographics can be simple, such as pyramid-shaped graphs about ancient Egypt, or complex, multi-layered presentations such as the IVLA’s Periodic Table of Visualization Methods. The massive infographics on the Kulula Airlines fleet of airplanes is a wonderful and novel example of using data visualization.[23] It is important to point out that it is easy to mislead with graphics, both intentionally or inadvertently. You should always check and re-check any infographic you develop for accuracy and bias. Soliciting external feedback can help you verify your work. (For a real-world example of misleading data visualization, go here.) As for the creation process, there are several helpful tools, including Microsoft Excel, Hohli Charts and Google Charts for making a variety of graphs; Gliffy for making flowcharts, Venn diagrams, etc.; and Visual.ly, Piktochart, and Infogr.am for making dynamic infographics.

An often overlooked component of presentation is the presenter him or herself. Many visual literacy scholars consider facial expression and body language to be key aspects of visual communication,[24] with some including broader performance aspects such as object use and placement.[25] How you present has significant impact. You should give careful thought to attire, stance, gestures, and expressions—especially when presenting to audiences of nationalities that may have different cultural associations from your own.

Exercise: Putting it All Together

- First, type out a thesis statement and three supporting arguments.

- Next, determine your audience.

- Now, using only images (which cannot contain text), demonstrate both your thesis statement and three supporting arguments. You can create images, use found images, or both.

- Each component can be either a single image (if this clearly communicates the thesis or argument) or a multimedia project (such as a Prezi) linking multiple images.

- Create correct citations for any image you did not create, using the APA or MLA style.

- Share your work by emailing it to a friend, using it for a class, or publishing it online in a blog or elsewhere.

Going Forward

Many believe that we are living in the most visual era yet, with today’s students being the most visually immersed generation the world has seen. Visual literacy has never been more critical, and is considered a key workplace skill[26] viewed by employers as on par with the ability to read and write.[27] Now, more than ever, it is critical to become aware of your own visual communication skills, to actively practice and improve them, and to create new work. There has never been a greater need, or potential, for creators to actively and ethically reach out and share their work with others. In this chapter, we have tried to give you an outline for using images, as well as some resources to help you on your way. We have walked, along with our friend Louis, through the landscape of visual literacy. You may wonder how everything worked out with him, but we intentionally left this open, because that question is for you to answer. Now it is your turn to go out and share your voice: there is a world waiting to be read and be visualized.

Select Quotations

Francis Bacon

Emblem…reduces intellectual conceptions to sensible images; for an object of sense always strikes the memory more forcibly and is more easily impressed upon it than an object of the intellect…And therefore you will more easily remember the image of a hunter pursuing a hare, of an apothecary arranging his boxes, of a pedant making a speech, of a boy repeating verses from memory, of a player acting on the stage, than the mere notions of invention, disposition, elocution, memory, and action.[28]

Henry Holmes Smith

Symbol systems and symbolic action constitute not only the greatest perils, but also the greatest hopes of mankind.[29]

Philip Yenawine

[Visual literacy] involves a set of skills ranging from simple identification—naming what one sees—to complex interpretation on contextual, metaphoric, and philosophical levels. Many aspects of cognition are called upon, such as personal association, questioning, speculating, analyzing, fact-finding, and categorizing. Objective understanding is the premise of much of this literacy, but subjective and affective aspects of knowing are equally important.[30]

Tad Simons

‘Seeing is believing’ goes the old saying, but this axiom has never been less true than it is today. We live in an age where photos, video, and film can be digitally altered to represent any reality imaginable . . . so it has never been more important to acquire the intellectual skills necessary to distinguish between visual fact and fiction, information and manipulation, reporting and propaganda.[31]

Roger Fransecky and John Debes

When developed, [visual literacy skills] enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, symbols, natural or man-made, that he encounters in his environment. Through the creative use of these competencies, he is able to communicate with others. Through the appreciative use of these competencies, he is able to comprehend and enjoy the masterworks of visual communication.[32]

Additional Resources

- A Periodic Table of Visualization Methods

- Columbia University’s Image Size and Resolution Guide

- David McCandless’ Ted Talk

- David McCandless’ Blog

- Edward Tufte’s Website

- Boston University’s Guide to Finding and Using Images

- Colgate University’s Image Citation Guide

- Christine L. Sundt’s Copyright & Art Pathfinder

- International Visual Literacy Association Website

- ACRL Visual Literacy Standards Graphic

- ACRL Visual Literacy Standards Website

Bibliography

Brill, Jennifer, Kim Dohun, and Robert Branch. “Visual Literacy Defined−The Results of a Delphi Study: Can IVLA (Operationally) Define Visual Literacy. Journal of Visual Literacy 27, no. 1 (2007): 47–60.

Brumberger, Eva. “Visual Literacy and the Digital Native: An Examination of the Millennial Learner.” Journal of Visual Literacy 30, no. 1 (2011): 19–47.

Christopherson, Jerry. “The Growing Need for Visual Literacy at the University.” In VisionQuest: Journeys Toward Visual Literacy, edited by Robert Griffin, J. Hunter, C. Schiffman, & W. Gibbs, 169–174. Philadelphia: International Visual Literacy Association, 1996.

Flynn, William. L. “Visual Literacy—A Way of Perceiving, Whose Time Has Come.” Audiovisual Instruction 17, no. 5 (1972): 41–42.

Hortin, John. “Visual Literacy and Visual Thinking.” In Contributions to the Study of Visual Literacy, edited by Lucile Burbank and Dennis Pett, 92–106. Philadelphia: International Visual Literacy Association, 1983.

Ipri, Tom. “Introducing Transliteracy: What Does it Mean to Academic Libraries?” College & Research Libraries News 71, no. 10 (2010): 532–567.

Jacobson, Trudi. “How Metaliteracy Changed My Life, My Teaching, and My Students’ Experiences.” Paper presented at the Academic Libraries 2012 Conference, Syracuse, NY. June 2012, http://www.nyla-asls.org/AcademicLibrariansConference/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/panel_presentation_public.pdf.

Lengler, Ralph, and Martin J. Eppler. “A Periodic Table of Visualization Methods.” Visual-Literacy.Org, http://www.visual-literacy.org/periodic_table/periodic_table.html.

Mackey, Thomas P., and Trudi E. Jacobson. “Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries 72, no. 1 (2011): 62–78.

Newton, Julianne H. The Burden of Visual Truth: The Role of Photojournalism in Mediating Reality. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000.

Thomas, Sue, Chris Joseph, Jess Laccetti, Bruce Mason, Simon Mills, Simon Perril, and Kate Pullinqer “Transliteracy: Crossing Divides.” First Monday 12, no. 12, 2007. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v12i12.2060.

- Visual Literacy Task Force. “Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” College & Research Libraries News 73, no. 2 (2012): 97–104. ↵

- Velders, Teun. “The Roots of Visual Literacy: Reflections on an Historical Perspective.” Journal of Visual Literacy 20, no. 1(2000): 7. ↵

- Bacon, Francis. The Works of Francis Bacon. Vol. 4, Translations of the Philosophical Works. Edited by James Spedding, Robert Ellis, and Douglas Heath. London: Longman, 1857, 437. ↵

- Pett, Dennis. “One Person’s Perspective: History of the International Visual Literacy Association.” International Visual Literacy Association, 1988. https://web.archive.org/web/20130207145009/http://ivla.org/drupal2/content/one-persons-perspective. ↵

- Smith, Henry Holmes, James Enyeart, and Nancy Solomon. Henry Holmes Smith: Collected Writings 1935–1985. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1986. ↵

- Daly, James. “Life on the Screen: Visual Literacy in Education.” Edutopia, 2004. http://www.edutopia.org/lucas-visual-literacy. ↵

- Burmark, Lynell. Visual Literacy: Learn to See, See to Learn. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002; Messaris, Paul. Visual “Literacy”: Image, Mind, and Reality. Boulder: Westview Press, 1994. ↵

- Daly, James. “Life on the Screen: Visual Literacy in Education.” Edutopia, 2004. http://www.edutopia.org/lucas-visual-literacy. ↵

- Chen, Yih. “Design Features of Visual Symbols.” Audiovisual Instruction 17, no. 5 (1972): 22–24. ↵

- Daly, James. “Life on the Screen: Visual Literacy in Education.” Edutopia, 2004. http://www.edutopia.org/lucas-visual-literacy. ↵

- Zuern, John. “Diagram, Dialogue, Dialectic: Visual Explanations and Visual Rhetoric in the Teaching of Literary Theory.” In Visual Media in the Humanities: A Pedagogy of Representation, edited by Kecia Driver McBride, 47–73. Knoxville, TN: Univ. of Tennessee Press/Knoxville, 200, 47–48. ↵

- Montogomery, David. “Flowers, Guns and an Iconic Snapshot.” Washington Post, March 18, 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com. ↵

- Newman, Bruce. “Some Concerns about Pinterest.” Westchester County Business Journal 48, no. 9 2012):18. ↵

- Chen, Yih. “Design Features of Visual Symbols.” Audiovisual Instruction 17, no. 5 (1972): 22–24. ↵

- Elkins, James. Visual Studies: A Skeptical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2003. ↵

- Avgerinou, Maria, and John Ericson. “A Review of the Concept of Visual Literacy.”British Journal of Educational Technology 28, no. 4 (1997): 280–291. ↵

- “What Resolution Should Your Images Be?” Media Center for Art History, Columbia University. http://learn.columbia.edu/mc/resources/documents/resolution-guide.pdf. ↵

- Klosowski, Thorin. “Clever Uses for Reverse Image Search.” Lifehacker (blog), April 16, 2013, http://lifehacker.com/clever-uses-for-reverse-image-search-473032092. ↵

- Newman, Bruce. “Some Concerns about Pinterest.” Westchester County Business Journal 48, no. 9 2012):18. ↵

- Cohen, Patricia. “Yale Press Bans Images of Muhammad in New Book.” New York Times, August 13, 2009. ↵

- Avgerinou, Maria, and John Ericson. “A Review of the Concept of Visual Literacy.”British Journal of Educational Technology 28, no. 4 (1997): 280–291. ↵

- Arnheim, Rudolph. “Gestalt Psychology and Artistic Form.” In Aspects of Form: A Symposium on Form in Nature and Art, edited by Lancelot Whyte, 196–208. New York: Pellegrini & Cudahy, 1951. ↵

- Krum, Randy. “Infographic Airplane! From Kulula Airlines.” Cool Infographics (blog), February 19, 2008, http://www.coolinfographics.com/blog/2010/2/8/infographic-airplane-from-kulula-airlines.html. ↵

- Messaris, Paul. Visual “Literacy”: Image, Mind, and Reality. Boulder: Westview Press, 1994; Fransecky, Roger, and John Debes. Visual Literacy: A Way to Learn—a Way to Teach. Washington: Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1972. ↵

- Debes, John. “The Loom of Visual Literacy: An Overview.” In Proceedings: First National Conference on Visual Literacy, edited by ClarenceWilliams and John Debes, 1–16. New York: Pitman, 1970. ↵

- Burmark, Lynell. Visual Literacy: Learn to See, See to Learn. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002. ↵

- Simons, Tad. Preface to Visual Literacy: Learn to See, See to Learn by Lynell Burmark, v–vi. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002. ↵

- Bacon, Francis. The Works of Francis Bacon. Vol. 4, Translations of the Philosophical Works. Edited by James Spedding, Robert Ellis, and Douglas Heath. London: Longman, 1857, 437. ↵

- Smith, Henry Holmes, James Enyeart, and Nancy Solomon. Henry Holmes Smith: Collected Writings 1935–1985. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1986, 89. ↵

- Yenawine, Philip. “Thoughts on Visual Literacy.” In Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy Through the Communicative and Visual Arts, edited by James Flood, Shirley Heath, and Diane Lapp6. New York: Macmillan Library Reference, 1997, 845. ↵

- Simons, Tad. Preface to Visual Literacy: Learn to See, See to Learn by Lynell Burmark, v–vi. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002, v–vi. ↵

- Fransecky, Roger, and John Debes. Visual Literacy: A Way to Learn—a Way to Teach. Washington: Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1972, 7. ↵