Messages from Writers on Writing and Education

“The Generation and Uses of Chaos”: Rhetorical Invention as the Taming of a Wild Garden

Reflection

Dan Ehrenfeld

In 1991, George R. R. Martin began writing A Game of Thrones, a fantasy novel that would eventually become a New York Times bestseller and an Emmy award-winning HBO series. As of this writing, Martin is seven years late delivering the sixth book of the series (Flood, “Barbarians”). His fans are not happy. When he says that he’s going on vacation or watching a football game, he gets hate mail (“how dare you do that, finish the book”) (Flood, “Getting More”). He says the book “will be done when it’s done” (Brown).

Conventional wisdom would say that Martin needs discipline. He needs plans. He needs schedules and outlines. But Martin’s own explanation of his writing process makes it clear that he’s not that kind of writer. Speaking to the Guardian in 2011 he said, “I think there are two types of writers, the architects and the gardeners….The architects plan everything ahead of time, like an architect building a house. They know how many rooms are going to be in the house, what kind of roof they’re going to have, where the wires are going to run, what kind of plumbing there’s going to be. They have the whole thing designed and blueprinted out before they even nail the first board up. The gardeners dig a hole, drop in a seed and water it … And I’m much more a gardener than an architect” (Flood, “Getting More”). For Martin, planning a piece of writing means starting with a seed of a story. He digs a hole and plants that seed. He waters it.

But he’s never quite sure what’s going to sprout out of the ground. He doesn’t know how many branches it’s going to have. He has to let it emerge. In its own time. On its own terms.

Unlike Martin, I don’t have a fanbase that sends me hate mail. If I miss a deadline, no one will notice except the editor. But I’m definitely a “gardener.” I sometimes feel, like Martin, that I have no idea where a piece of writing is going. I dive in before I’m ready. I get stuck. I try something different. I don’t know what I’m doing. And I have no idea whether I’m going to pull it off.

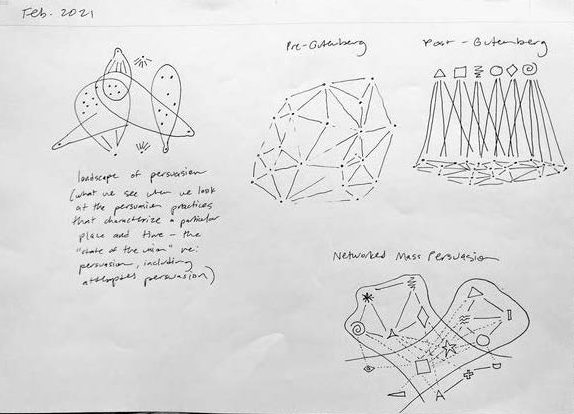

Sounds terrible, right? But being a “gardener” has actually served me well. Each time I start a project, there’s a “seed” that I know I want to plant. For Martin, that seed was a fully-formed vision that came to him one day—a vision of a boy witnessing a beheading and then finding some direwolf pups in the snow (Gilmore). For me, a scholar who studies rhetoric and writing, the visions are a little bit less dramatic. For the past few years, I’ve been asking myself questions about persuasion, activism, and social media: What do people share? How do they coordinate with one another to spread certain ideas? How do they influence one another? I’ve doodled some ideas, which is one way that I try to tend a garden that’s particularly weedy. The vision that keeps coming back to me—the “seed” of this project—is a zoomed-out view of the whole “ecology” within which persuasion happens. This doodle isn’t a blueprint. It’s just a vision, put on paper. Maybe nothing! Or maybe a seed of something. When I drew the doodle that you see here, I was thinking a lot about how our “rhetorical ecologies” have changed over the course of three different eras—the pre-Gutenberg era (before the advent of print), the post-Gutenberg era (after the advent of print), and the digital era. In this doodle, you can see that I’m trying to map out these different eras. It was my first try. In the months after I made this doodle, I wrote pages and pages of notes and outlines. Sometimes it led nowhere. Sometimes I started to find my footing. Even now, there are moments when I curse the mess of this project. I tell myself that I’m never going to do this again. Next time I’m going to plan this all out, like an architect. No more waiting. Not more tending the soil. No more uncertainty. No more false starts. I’m just going to draft the blueprints and execute them.

But I’m not an architect. Trained in rhetorical studies, I know that new ideas and arguments are not just invented during the “prewriting” phase of a project; they are invented throughout the writing process. Rhetoricians call this inventio, or invention. As compositionist Janet Emig teaches us, writing is “a unique form of learning” that eventually yields “a record of the journey from jottings and notes to full discursive formation” (Lauer 82). Ann Berthoff similarly writes that “meanings don’t come out of the air, we make them out of a chaos of images, half-truths, remembrances, syntactic fragments, from the mysterious and unformed.” And here’s my favorite part from Berthoff: “When we teach pre-writing as a phase of the composing process, what we are teaching is not how to get a thesis statement but the generation and uses of chaos” (qtd. In Garrett, Landrum-Geyer, and Palmeri).

Eventually, I know that I want my work to be valued by a community of rhetoric and writing scholars around the world. In other words, whatever I write needs to help my field get closer to its goal—understanding how rhetoric and writing work. But the alchemical process of making order out of chaos usually remains a private struggle. Emig and Berthoff perfectly describe this “gardening” approach to writing. It’s not about the finished product. It’s about the generation and uses of chaos. The doodling, the note-taking, the crumpling of papers—all of these practices should be understood not as steps done before writing but as the writing process itself.

If I’ve done my job well, the dirty work of taming this garden won’t be visible to my audience at all. Only I will know that one of my chapters was based on the doodle that you see here. Only I will know that I couldn’t have developed the argument that I developed if I hadn’t spent months doodling and jotting down half-formed thoughts. In my experience, this private self-torture is a crucial part of the writing process. And yes, designing the architecture of a text is important. I’ve done some of that too. But giving myself the time that I need to wrestle with a project—to tame it, but also to watch it get out of control—is important. It’s something that you can’t really plan in advance. There is no blueprint. You just have to let it happen.

By opening up my notebook and sharing one of my doodles, I hope that I’ve been able to offer a glimpse of “the generation and uses of chaos.” This doodle, like many of my doodles over the years, is a record of an obsession working itself out. And though I haven’t read Martin’s books, my guess is that his success is at least partly attributable to this “gardening” approach to inventio. When Martin began writing A Game of Thrones, it was just a few mental images. And then it became a story. And then it became a trilogy. As he cultivated a garden of characters and plotlines, he re-envisioned the whole thing as a seven-part series. As of this writing, an HBO spinoff is in the works, with Martin serving as co-creator and co-producer. Who better to manage this chaos than a gardener tending such a wild garden?

Works Cited

Brown, Rachael. “George R. R. Martin on Sex, Fantasy, and a Dance with Dragons.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 17 May 2019, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/07/george-rr-martin-on-sex-fantasy-and-adance-with-dragons/241738/.

Flood, Alison. “George RR Martin: Barbarians at the Gate.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 13 Apr. 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/apr/13/george-rr-martin-game-thrones.

———. “Getting More from George RR Martin.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 14 Apr. 2011, www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2011/apr/14/more-george-r-r-martin.

Garrett, Bre, et al. “Re-inventing invention: A performance in three acts.” The New Work of Composing, edited by Debra Journet, Cheryl E. Ball, & Ryan Trauman, Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2012, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/nwc/chapters/garrett-et-al/

Gilmore, Mikal. “George R. R. Martin: The Rolling Stone Interview.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 19 July 2020, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/george-r-r-martin-the-rolling-stone-interview-242487/

Lauer, Janice M. Invention in Rhetoric and Composition. Parlor Press, 2004.