Main Body

Appendix D: To What Extent Are Small-Scale Coffee Producers in Latin America the Primary Beneficiaries of Fair Trade? by Larissa Zemke

[These sample student papers are provided only as examples of successful student research: they are not meant to prescribe any standard paper format and the content of each paper represents purely the author’s view.]

This paper focuses on the socioeconomic impacts of fair trade on small-scale coffee producers in Latin America. The fair trade mechanism has shown some benefits to small-scale farmers on a micro-level and has been gaining firm grounds as a socially responsible initiative. This paper explores the extent to which small producers and cooperatives are primary beneficiaries of fair trade. Nevertheless, a critical approach to the fair trade mechanism and its implementation is also necessary, in order to evaluate and improve its effectiveness. The paper sets off by discussing the origin of the concept, goals, and positive impacts of fair trade. Subsequently, a discussion on the concept’s weaknesses is obtained through an assessment of the socioeconomic impacts of sustainable livelihoods, poverty alleviation, capacity building, and empowerment on a local level in Latin America. The impacts analyzed focus on the following respective areas: human, social, financial, and physical capital of the small-holder coffee producers through assessing various case studies addressing the impacts of fair trade coffee in Latin America. I conclude with an analysis of the one-way link that fair trade constructs between the consumers in developed countries and producers in developing nations, through societal marketing, which promotes ethical consumerism.

Introduction

Fair Trade1 presents an alternative to traditional forms of international aid,2 because the livelihoods of small-scale producers and communities, as well as the economic growth of developing nations, are supported through trade, as they receive a “fair” price from developing nations for the goods they produce. The founders of the fair trade concept, Nico Roozen and Frans van der Hoff, were inspired by the statement of a Mexican coffee farmer: “We are not beggars, we only need a fair price for our coffee…We want to put an end to the centuries of exploitation that we have experienced…and [gain] the (market) power to change [our] destiny.”3 This exploitation may be explained by the dependency theory, which states that the terms of trade between center, developed nations, and the periphery, developing nations, is unbalanced and unfair.4 Immanuel Wallerstein’s center-periphery model5, may be applied to analyze this relationship, as the underdeveloped Latin American coffee smallholders, the periphery, are exporting the raw material of coffee to the developed, industrialized world, the core, and, the market acts as the means by which the core exploits the periphery.6 Fair trade aims to mitigate this unfair power relationship through its sustainable initiatives.

In 1981, the Dutch foreign-aid activists founded the world’s first fair trade cooperative, the Union of Indigenous Communities in the Isthmus Region (UCIRI), in the Oaxaca region of Mexico, with the objective of fighting the root causes of persistent poverty among local coffee farmers. They adopted policies aimed at readjusting low coffee prices and reducing farmers’ heavy debts7 in order to render them more competitive on the world market. The founders went on to establish the Max Havelaar label, which successfully elevated and stabilized coffee prices in Oaxaca, Mexico, by eliminating the middleman8 and shortening the coffee production value chain. The small-scale farmers were able to receive a higher price: $0.95 per kg of coffee instead of the previous rate of $0.25.9 Certification programs were founded in order to ensure that ideals and standards of fair Trade are implemented, which became joined under the umbrella group known as the Fair Trade Labeling Organizations International (FLO).10

The stakeholders in the fair trade coffee network include producer groups in developing nations, umbrella organizations, buyers in developed nations, roasters, retailers, and consumers.11 The intended primary beneficiaries of the fair trade concept are small-scale producers in developing nations. The main issue that these producers face is the downward trend of coffee prices in the global market since there is an excess supply over demand for coffee. During the 1900s, the world’s coffee production has increased at an average annual rate of 3.6 percent, whereas demand has merely increased by 1.3 percent per year.12 As a result, coffee smallholders have been unable to cover their production costs and improve their livelihoods.

FLO states that fair trade standards are designed to support the sustainable development of small-scale producers and agricultural workers in the poorest countries in the world.13 Fair trade’s key objectives include ensuring that producers receive prices that cover their average costs of sustainable production; providing a fair trade premium14; investing in social, economic, and environmental development projects; enabling prefinancing for producers; facilitating long-term trading relationships; enhancing producer power over trading process; and setting clear minimum and progressive criteria to ensure that conditions of the production and trade of all fair trade certified products are socially, economically fair and environmentally responsible.15

The following section discusses the extent to which fair trade standards are effectively implemented in improving the lives of small-scale coffee producers in Latin America—the core—which supplies 78 percent of the world’s Fair Trade-certified coffee to consumers in developed nations—the periphery.16

Smallholders and Fair Trade

In order to fully evaluate the socioeconomic impacts of fair trade coffee on small-scale producers, this section uses an “asset analysis” based on four assets, or types of capital17: social, human, financial, and physical capital.18

Human Capital

The analysis on human capital focuses on capacity building, which enhances the small-scale coffee producers’ understanding, skills, and access to information, knowledge, and technical training to enable them to perform effectively to sustain and improve their livelihoods.19

The coffee cooperative union of Jinotega, Nicaragua, called Soppexcca, provides technical support to small-scale coffee farmers to achieve capacity building through workshops and direct personal assistance, which provides an opportunity for them to both adequately access the fair trade market and obtain a higher price for their coffee, and ensures that their coffee meets required quality standards.20 Furthermore, the case study has shown that capacity building of the Jinotega smallholders resulted in an increase of their competitiveness on the fair trade market.

The development of sustainable and improved livelihoods also includes improvement in human capital, related to gender equity and the role of rural women in fair trade activities.21 Improvements have been shown through the formation of Soppexcca’s Café de las Mujeres (“Women’s Coffee”), which has been encouraging an increase in women’s participation in fair trade coffee production and generating household income.

However, a case study, comparing TransFair USA (TF)22 cooperative participants and non-participating farmers in three Latin American countries on the socioeconomic indicators of well-being, education and health outcomes,23 shows varied results. The study’s path analysis does conclude that TF participation tends to have a positive influence on current participation in primary education.24 It is difficult to assess the extent to which fair trade initiatives positively impact the human capital of Latin American smallholders since numerous factors’ effects must be considered, such individual households’ priorities and cultural traditions. Nevertheless, capacity building is crucial to encouraging sustainable development, as it is necessary for smallholders, members of cooperatives, to be able to operate and make unified decisions regarding how to invest their fair trade premium most efficiently. Capacity building fosters a fairer balance in power between the fair trade coffee roasters and retailers in developing nations—the periphery—and the smallholders in Latin America—the core.

Social Capital

The evaluation of changes in the social capital of small-scale coffee farmers in Latin America examines the process of empowerment, the social recreation, levels of migration, and participation and decision making within the cooperative as well as within the community.25 Soppexcca’s organizational objectives succeeded in opening up spaces for the empowerment of their members, encouraging Jinotega smallholders to take part in events and inducing them to feel that they are part of a system that belongs to them, and establishing closer relations with the general manager of the organization as well as between buyers and cooperative members.26 The Soppexcca cooperative union has shown an increase in the engagement of the smallholders in the cooperative’s governance and decision-making, as it “consists of a general assembly and a board of directors made up of [small-scale] producer members.”27 Jinotega’s small-scale coffee producers “became part of a fair trade system, not only in events organized by their cooperative, but also at the community level.”28 Their interactions with development included involvement in “health and peace committees, sports activities, parents’ committees at school; and with national or international development NGOs operating in their regions.”29 Fair trade’s empowerment objective stresses the importance of allowing smallholders to experience unity and have their voice count in order to encourage production efficiency and sustainable livelihoods. However, the efficiency of self-governance of smallholders is debatable. The president of Soppexcca has alluded to the problem of inefficiency of many cooperatives due to, “high levels of illiteracy…low educational levels, and the lack of knowledge about how to manage legal, commercial, organizational, and fair trade requirements,”30 amongst the members and the board representatives. Furthermore, as a result of a lack of education, there is “a lack of knowledge about the international coffee market [and fair trade] and the low capacity to interpret its trend,” 31which inevitably leads to weak international negotiation power in the supply chain and reduces efficiency of small-scale coffee producers.

A case study on the Guatemalan Loma Linda Community investigates the local dynamics of the social vision of fair trade32 and addresses the significance of solidarity in contributing to sustainable livelihoods of smallholder coffee producers. The cooperative was founded in 1977 by a Spanish Catholic priest, Father Celestino, emphasizing “the significance of individual rights to livelihood and the importance of employment and access to land,”33 which challenged the power legacy of local landlords since colonial times. Furthermore, it banned middlemen and prevented the sale of land and individual commercialization of products, which permitted producers to legitimize themselves as the organized embodiment of solidarity relations.34 In the 1980s, the Loma Linda Community joined the Federation of Coffee Cooperatives of Guatemala (FEDECOCAGUA), which promoted fair trade practices and economies of scale. However, discontent amongst smallholders soon arose due to lack of circulation of information and transparency, and queries on how the fair trade premium funds were distributed to local cooperatives, as they did not seem to directly reach to local producers, resulting in discontent and political resentment against FEDECOCAGUA.35 The study reveals the problems that fair trade faces in ensuring that the fair trade premium trickles down to reach the smallholders and improve their livelihoods, and how the,“paths to fair trade generate different texts36 in a context in which people’s life worlds become fractured to embody a diversity of solidarity and fair trade categories.”37

Moreover, a case study conducted in rural region of Oaxaca, Mexico, in 2004, questions the sustainability of the fair trade–organic coffee mechanism in regard to the migration opportunities.38 The study explains that the increased trend in migration of labor in the Cabeza del Rio community in search of greater opportunities abroad has caused “wages [to double] in five years…[while] the fixed price of fair trade coffee had not risen in over ten years.”39 This raises the question of how efficient the FLO and Fair Trade certifiers are in investigating and ensuring that the fair trade coffee price and premium amount paid to smallholders adequately meets the minimum living standards of smallholders and provides poverty alleviation.

Financial Capital

An examination of the financial capital40 reveals the contribution fFair trade has had on raising the living standards of small-scale coffee producers in Latin America.41 In theory, fair trade provides a stable coffee price and a premium to small-scale producers to effectuate poverty alleviation. Additionally, it encourages local smallholders to compete in production of quality coffee. However, it is important to investigate these claims more critically and question the extent to which the fair trade premium (USD$0.010)42 benefits and alleviates small-scale producers from poverty.

A study focusing on smallholders in Jinotega, Nicaragua, reveals that one disadvantage of trading with fair trade organizations is that they use the “open account payment” method, which does not offer immediate payment for each sack of coffee delivered.43 This has shown to create the risk that some producers will breach contracts, especially when the international price of coffee is similar to the fair trade price agreed upon when the contract was signed, in order to receive their payment immediately.44 This behavior also causes trade relationships between the smallholders and their cooperatives and the international buyers to suffer, and weakens the international negotiation power of the coffee smallholders.

Furthermore, the extent to which the fair trade price paid to smallholders is fair is debatable. Even though the smallholders in Jinotega, Nicaragua, are able to attain a higher price—“4.5 times [higher] than before they joined the fair trade system”45—for their coffee through Fair Trade certification, are they the primary beneficiary of the elevated fair trade price?

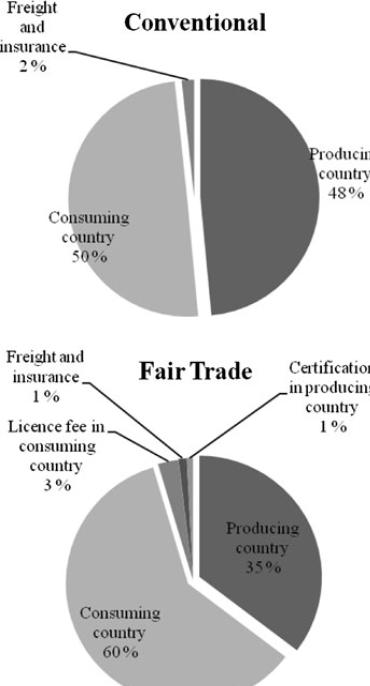

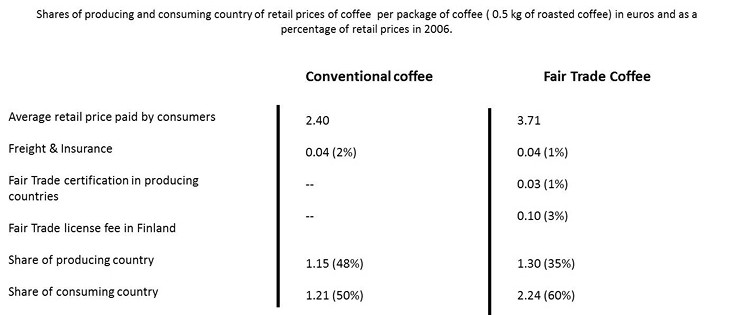

The following study investigates the fair trade coffee trade between Nicaraguan smallholders and Finnish consumers, by questioning how efficient fair trade is in redistributing wealth from consuming countries to producing ones.48 This alludes to the coffee paradox theory that argues that the global coffee business is creating wealth in the consuming countries—the core—while smallholder farmers and laborers in developing nations—the periphery—are exploited and remain in poverty.49 It is questionable whether fair trade mainly empowers roasters and retailers50 rather than small-scale coffee producers. The study assesses what percentage of the final retail price paid by consumers in the developing nation, in this case Finland, actually goes to the small-scale coffee producers in Nicaragua. The Finnish customs statistics estimate that “the average price paid for all green coffee imported to Finland in 2006 [was €1.95 per kilogram and]…estimates a transportation and insurance cost of €0.07 per kilogram of green coffee.”51 Additionally, the study estimates that approximately 1 percent of the retail price paid by Finnish consumers goes to international coffee trade stakeholders: export companies or trading houses. Table 1 and Figure 1 provide evidence that a higher portion, 60 percent, of the final retail price for fair trade coffee goes to consumer country than the producer country, which receives merely 35 percent. On the other hand, the purchase of conventional coffee resulted in 50 percent of the retail price going to the consumer country and 48 percent going to the producer country. The study explains that retailers’ reason for taking very low margins from their conventional coffee sales is to attract customers.52 The Finnish retailers or roasters charged significantly higher margins for fair trade coffee than for conventional coffee, and thus a greater portion of the premiums paid by fair trade consumers, the ethical donations, remains in Finland, the consuming nation, rather than being transferred to the Nicaraguan coffee smallholders, as fair trade initiatives advocate.53 As a result, it may be concluded that fair trade is inefficient in redistributing the wealth from the developed consuming nations—the periphery—to the developing nations—the core—as a greater portion of the fair trade retail price remains in the consuming nation. It is arguable to what extent this claim is valid, as the study does not mention whether the difference in purchasing power in Nicaragua and Finland is considered.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that smallholder members of coffee cooperatives only sell a part of their coffee supply to fair trade markets, since the volatile coffee price may be periodically higher in mainstream markets than in cooperatives.54 This was the case during the harvest season of 2005–2006 in Nicaragua during which the Exportadora Atlantic, SA, paid an average of USD$0.83 per pound of coffee while the Fair Trade certified cooperative merely paid an average of USD$0.06 more per pound of coffee. Yet, there were times when the export company offered a higher price.55 It must also be taken into account that Fair Trade certified cooperatives also deduct a portion from the price sold to cover operational certification costs, which were 5.5 cents per pound of exported coffee in 2005–200656 and thus don’t receive full the minimum fair trade price for all their produced coffee.

Moreover, the French critic Christian Jacquiau’s controversial book, Les coulisses du commerce equitable, criticizes the effectiveness of fair trade and the Max Havelaar Foundation, questioning “how much of that money ends up in the pockets of farmers in developing countries.”57 Jacquiau states, “There are 54 inspectors around the world, working on a part-time freelance basis to check and control a million producers. These checks do not take place on the ground but in offices, hotel rooms, or even by fax.”58 He refutes Max Havelaar’s claim that, “€50 million (SFr79 million) has been distributed among small farmers…[while] the organization claims to work with a million producers.”59He states, “Here the dream falls apart. [Producers] therefore each receive just €50 a year—or €4 a month.”60 Jacquiau’s claims have raised debates as to whether fair trade’s higher prices and standards are effective in alleviating the poverty of the small-scale coffee producers and encouraging sustainable livelihoods.

Physical Capital

Finally, the improvement of Latin American small-scale coffee producers’ livelihood is further assessed by addressing their physical capital. Fair trade and other ethical certifications aim to facilitate exchange and protect health and safety61 of workers; however, “developing countries might suffer from structural bottlenecks,”62 to comply with these standards. These bottlenecks often involve lack of adequate infrastructure, processing technologies, and national regulatory bodies.63

The case study of Jinotega’s smallholders and community demonstrates weaknesses in efficiently in investing the premium funds to enhance the local infrastructure. Premium funds have shown to be used “for disjointed, ad hoc projects [that] may not have optimized the potential benefit of such funds.”64 Soppexcca’s social project cocoordinator explains that this is because funds collected from the air trade social premium are insufficient to consider larger community development work such as improving road infrastructure and water and electricity services.65 In addition to an insufficient amount of funding, there is also a limited or even a lack of government support.66 The lack of adequate physical services such as communication and electricity in most rural communities in Jinotega, Nicaragua, makes it difficult for smallholders high in the mountains and Soppexcca to communicate, through the radio or paper leaflets sent by bus.67 The existence of inefficient modes of communication hinders transparency and open communication between the cooperative administrations and the small-scale coffee producers in order to ensure efficiency of fair trade premium–financed projects.

From these case studies, it can be deduced that the fair trade premium is good concept; however, more thorough investigation by FLO is required to ensure that the amount of fair trade premium paid to smallholders is sufficient to finance projects to develop the physical capital and infrastructure of the communities.

Smallholders and Consumers

Having analyzed the link between Latin American smallholder coffee producers and fair trade retailers and roasters in light of the dependency theory, this section examines the link that fair trade constructs between the Latin American small-scale coffee producers and the consumers in developing nations. The weaknesses of the implementation of fair trade initiatives revealed in research results have raised the question whether fair trade is merely a societal marketing68 strategy that promotes ethical/green consumption.69 Fair trade seems to create a mode of connectivity to strengthen producer–consumer relationships70 by offering consumers an opportunity to donate to charity at a distance.71

It is debatable whether Alternative Trading Organizations such as FLO are successful in altering power relationships between producers and consumers or whether they are merely another profit-making business that promotes consumerism.72 The case study conducted on the fair trade coffee trade between Finland and Nicaragua provides supporting evidence to the coffee paradox theory’s claim that the global coffee business is creating wealth in the consuming countries—the core—while smallholder farmers and laborers in developing nations—the periphery—are exploited and remain in poverty.73 The study demonstrates that a greater percentage of the final retail coffee prices actually goes to the consuming nation instead of the producer nation. The artificial bond created between consumers and the small-scale coffee producers through societal marketing’s visuals gains the sympathy of consumers and makes them believe they are being socially responsible citizens by purchasing ethical products to support the less fortunate smallholder producers.

The coffee commodity is demystified, “as the hidden layers of information are peeled away to reveal the social and environmental conditions of the commodity’s production,”74 with visual presentations of smallholders and their farms. Yet one must question to what extent the information provided is accurate. The examination of fair trade product packaging has revealed that fair trade seems to apply deceptive packaging to attract consumers, as there are subtle differences in fair trade labeling among the different certifiers, Institute for Marketecology (IMO) and FLO, that define whether the product is Fair Trade Lite75 certified or Whole Product76 certified. The IMO claims to distinguish the Whole Product from a Fair Trade Lite product by placing the IMO Fair Trade label for a whole product on the front of the certified product’s packaging while the Fair Trade Lite label must be placed on the back. Nevertheless, the FLO labels the Fair Trade Lite and Whole Products in exactly the same manner, which provides ambiguity of the extent a product is fair trade. The fair trade product packaging of the Organic Very Dark Chocolate (71% Cacao) bar by Equal Exchange77 demonstrated inconsistencies in labeling, since the back side states: “By weight 100% Fair Trade content” and “Fair Trade and Social certified by IMO.” This does not adhere to IMO’s certification guideline that a Whole Product label must be placed on the front of the product packaging. This raises the doubt about how efficient the Fair Trade certifiers are in ensuring that products are labeled correctly and how they collaborate with fair trade advocates such as Equal Exchange. Additionally, a subtle difference exists between fair trade membership, which certifies a company’s commitment to fair trade principles, and Fair Trade certification, which is “certification…of the supply chains of specific products.”78 The distinction is one that consumers tend to overlook.

Fair trade consumption may be regarded as a means of encouraging altruistic79 behavior, as the consumer is manipulated to believe that through a simple purchase of a fair trade product he or she is donating for a greater cause, or “shopping for a better world.”80 Fair trade products have become “ethical luxury” goods”81 that allow consumers to reflect their political, socially responsible values in society. Consequentially, ethical/green consumption seems to act as justification for our overconsumption.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that fair trade’s link between smallholder producers in Latin America and consumers in the developed nations merely provides a one-way flow of information. Small-scale farmers often lack the knowledge about the consumers and the coffee market. A survey interviewing cooperative members on their understanding of fair trade demonstrated that merely three of fifty-three surveyed members regarded fair trade as a means of building relationships with foreign consumers or coffee roasters, and that they primarily viewed fair trade as a market transaction paying slightly higher prices than conventional coffee markets.82 Ultimately, the strongest, most beneficial link provided by fair trade seems to be the bond created between the small-scale producers and the roasters, as cooperative membership has shown to encourage capacity building and provide information about international coffee market trends. Capacity building plays a crucial role in enabling small-scale producers to invest their fair trade premiums efficiently to improve their livelihoods and international negotiating power.

Conclusion

This paper has revealed the benefits and weaknesses of the fair trade concept as a tool of international development. The in-depth analysis of the link that fair trade constructs between roasters and retailers in consuming nations and small-scale coffee producers in Latin America is compared to the link formed between the consumers in developed nations and the smallholders, through fair trade societal marketing. The research conducted has shown that, although the fair trade mechanism is a valid method of promoting sustainable development in developing countries, its implementation in developing nations and marketing should be more thoroughly refined. This would enhance its efficiency in promoting sustainable development and enhancing consumer credibility and support. We can conclude that the most beneficial link, provided by the fair trade mechanism, is the direct relationship link it creates between the small-scale producers and the roasters. Cooperative membership has shown improvements in the capacity of the smallholder’s human capital, which is vital to achieving sustainable development and improving the international negotiation power of the smallholders on the coffee market.

Endnotes

1. There is an important difference between the terms free trade and fair trade. Free trade is defined as the general openness to exchange goods and information between and among nations with few-to-no barriers-to-trade, whereas fair trade refers to exchanges, the terms of which meet the demands of justice. (Jeffrey Eisenberg, “Free Trade vs. Fair Trade,” Global Envision, October 26, 2005, http://www.globalenvision.org/library/15/834)

2. Ibid., 453.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Wallerstein’s model applies “a zero-sum game analysis of international trade… This model characterized the world system as a set of mechanisms which redistributes resources from the periphery to the core.” (Mine Aysen Doyran, “Latin America,” 2010: 8).

6. Ibid.

7. Jan Van der Kaaj, “Building a Sustainable Profitable Business: Fair Trade Coffee (A),” International Institute for Management Development, 2003, 2.

8. The “middleman” refers to local traders who monopolized the market. (Taken from Van der Kaaj, “Building a Sustainable Profitable Business (A),” 3.

9. Ibid.

10. Eric J. Arnould, Alejandro Plastina, and Dwayne Ball, “Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28, no. 2 (2009): 187.

11. Sarah Lyon, “Evaluating Fair Trade Consumption: Politics, Defetishization and Producer Participation,” International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30, no. 5 (2006): 453.

12. Jan Van der Kaaj, “Building a Sustainable Profitable Business: Fair Trade Coffee (C),” International Institute for Management Development, 2003, 6

13. “Aims of Fairtrade Standards, 2010,” Fair Trade Labeling Organizations International, December 5, 2010, http://www.fairtrade.net/aims-of-fairtrade-standards.html.

14. “A Fairtrade Premium of US$ 20 cents per pound is added to the purchase price and is used by producer organizations for social and economic investments at the community and organizational level” (“Benefits of fair trade for producers,” http://www.fairtrade.net/coffee.html).

15. Ibid.

16. Of the 78 percent of Latin American fair trade coffee, Mexico, Peru, Guatemala, Colombia, and Nicaragua are the largest exporters. (Joni Valkila, Perti Haparanta, and Nina Niemi, “Empowering Coffee Traders? The Coffee Value Chain from Nicaraguan Fair Trade Farmers to Finnish Consumers,” Journal of Business Ethics, 97 (2010): 257).

17. “In classical economics, capital is one of three factors of production, the others being land and labour. Goods with the following features are capital: It can be used in the production of other goods (this is what makes it a factor of production). It is human-made, in contrast to “land,” which refers to naturally occurring resources such as geographical locations and minerals. It is not used up immediately in the process of production, unlike raw materials or intermediate goods.” (http://www.wordiq.com), accessed 2010

18. Karla Utting, “Assessing the Impact of Fair Trade Coffee: Towards an Integrative Framework.” Journal of Business Ethics, 86 (2009): 129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9761-9

19. Ibid., 136.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. TF is “a third-party certifier [who] audits the supply chains of specific products from point of origin to point-of-sale against fair trade criteria…” ( “Reference Guide to Fair Trade Certifiers and Membership Organizations,” For a Better World: Issues & Challenges in Fair Trade, Issue 1, Fall 2010.)

23. Eric J. Arnould, Alejandro Plastina, and Dwayne Ball, “Does Fair Trade Deliver on Its Core Value Proposition? Effects on Income, Educational Attainment, and Health in Three Countries,”Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28, no. 2 (2009): 186.

24. Ibid.,198.

25. Utting, “Assessing the Impact,” 136.

26. Ibid., 137.

27. Ibid., 140.

28. Ibid., 137.

29. Ibid., 137.

30. Ibid., 140.

31. Ibid.

32. Alberto Arce, “Living in Times of Solidarity Fair Trade and the Fractured Life Worlds of Guatemalan Coffee Farmers, ” Journal of International Development, 21(2009): 1033.

33. Ibid., 1033–34.

34. Ibid., 1034.

35. Ibid.

36. “The term text ‘refers not to script alone, but any articulation of intelligibility, that is to say, of being’ (Michael Schatzki, Site of the Social: A Philosophical Account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change, Penn State Press, 2010, p.61.) Text is used here to encompass narratives, discourses, and speech-acts as languages of performance, weaving distinctions from differences in peoples’ diverse interpretations that constitute the fabric of solidarity and fair trade. This refers to the etymological root of the three meaning of the term ‘text’: generate, hit, and prepare, orienting the performance of networks and socially expressing different kinds of solidarity and the tasks involved in the coordination of fair trade and its involvement within social life.” (Arce, “Living in Times of Solidarity,” 1037, note 9.)

37. Ibid., 1036-7.

38. Jessica Lewis and David Runsten, “Is Fair Trade-Organic Coffee Sustainable in the Face of Migration? Evidence from an Oaxacan Community,” Globalizations, 5, no. 2 (2008): 275.

39. Ibid., 287.

40. Examining “financial capital” refers to the “financial resources used to support livelihood and [examine] how fair trade producers’ financial assets have changed over time.” (Utting, “Assessing the Impact,” 138).

41. Ibid., 138.

42. “Coffee: Benefits of Fair Trade for Producers,” Fair Trade Labeling Organization, 2010, http://www.fairtrade.net/coffee.html.

43. In this method, “buyers pay upon delivery of supply of coffee, which may take up to…four months”. Utting, “Assessing the Impact,” 139.

44. Utting, “Assessing the Impact,” 139.

45. Ibid.

46. Joni Valkila, Perti Haparanta, and Nina Niemi, “Empowering Coffee Traders? The Coffee Value Chain from Nicaraguan Fair Trade Farmers to Finnish Consumers,” Journal of Business Ethics, 97 (2010): 266.

47. Ibid., 266.

48. Ibid., 257.

49. Ibid., 259.

50. Ibid., 257.

51. Ibid., 265.

52. Ibid., 266.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid., 263.

55 Ibid.

56. Ibid., 264.

57. Ian Hamel, “Fair Trade Firm Accused of Foul Play,” Swiss Info, August 3, 2006, http://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/fair-trade-firm-accused-of-foul-play/5351232

58. Ibid.

59. Ibid.

60. Ibid.

61. Joseph E. Stiglitz and Andrew Charlton, Fair Trade for All (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 2005), 211.

62. Ibid., 211.

63. Ibid., 212.

64. Utting, “Assessing the Impact,” 138.

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

68. “Societal marketing emphasizes several aspects of responsible marketing, beyond simply focusing on the process of maximizing consumer purchasing. Societal marketing extends ahead of the company’s needs and seeks to meet the customer’s needs and societal needs. This allows for more sustainable success rather than short-term accomplishment.” (J. R. Ericson, “About Societal Marketing,” eHow, http://www.ehow.com/about_4571318_societal-marketing.html.) Accessed 2010.

69. Ethical consumerism or green consumption is defined as the consumption trend that reflects an increased concern and feeling of responsibility for society, which has led to remarkable growth in the global market for environment-friendly products. (Nina Mazar and Chen-Bo Zhong, “Do Green Products Make Us Better People?” Psychological Science, 21, no. 4 (August 27, 2009): 494–498. )

70. Lyon, “Evaluating Fair Trade Consumption,” 457.

71. Ibid.

72. Arnould, Plastina, and Ball, “Does Fair Trade Deliver?” 199.

73. Ibid., 259.

74. Lyon, “Evaluating Fair Trade Consumption,” 457.

75. A Fair Trade Lite product is afair trade product that contains 20% minimum fair trade content, “made with single/some Fair frade ingredients.” ( Nasser Abufahra, “How Do you Know It’s Really Fair Trade?” For a Better World: Issues & Challenges in Fair Trade, 1(Fall 2009): 6.)

76. There is a “50% [fair trade] content minimum for ‘whole product’ [Fair Trade] certification…”(Abufahra, “How Do you Know?” 6).

77. “Equal Exchange is a for-profit Fairtrade worker-owned, cooperative headquartered in West Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Equal Exchange distributes organic, gourmet coffee, tea, sugar, cocoa, and chocolate bars produced by farmer cooperatives in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Founded in 1986, it is the oldest and largest Fair Trade coffee company in the United States.” “Equal Exchange: About Our Co-Op” Equal Exchange, Inc.Accessed 2010. http://www.equalexchange.coop

78. “Reference Guide to Fair Trade Certifiers,” 4.

79. Altruism is a helping behavior that is motivated by a selfless concern for the welfare of another person. (https://www.psychologytoday.com/basics/altruism).

80. Ibid.

81. Valkila, Haparanta, and Niemi. “Empowering Coffee Traders?” 259.

82. Lyon, “Evaluating Fair Trade Consumption,” 458.