Main Body

6. Marketing Ethics: Selling Controversial Products

Legal and Ethical Constraints on Marketing and Advertising

This chapter explores the ethics of marketing and advertising. As the most visible form of marketing, advertising is one of the principal motors of a capitalist economy and also one of the largest modern industries: The global advertising market was valued at $495 billion in 2013 (the United States was the largest national market at $152 billion).1 Advertisements not only inform consumers of available products, services, promotions, and sales, they serve a vital business function by allowing brands to distinguish themselves from competitors, which rewards firms for improving the quality of their offerings. Advertising is a key ally for innovation, because advertising allows firms to create awareness and desire among consumers to buy new products. Despite these benefits, the advertising industry has long been suspected of using devious tactics. As a result, many consumers are highly skeptical and even disdainful of advertising in general.

Advertisers sometimes take the risk of shocking the public with their ads because they are seeking to break through the communications clutter of modern life. Today, the average American is exposed to a great number of advertising messages every day, with estimates running from several hundred to several thousand ads per day.2 In order to attract the public’s attention, advertisers may resort to appeals and tactics of questionable taste. Little wonder that more than half of Americans believe that advertising today is out of control. Social critics point to advertising as one of the most objectionable aspects of our consumer economy. From the billboards that blot out the countryside along highways, to the television shows that are interrupted every few minutes by outlandish commercials, to the mailboxes and e-mail accounts that become cluttered with direct marketing, advertising methods are often criticized for being intrusive, offensive, silly, and even dishonest.

As a result of the perceived abuses of advertising, national governments all over the world have imposed laws and regulations on the advertising industry. Every country or region has its own area of sensitivity. In many Muslim nations, for example, there are prohibitions against advertisements that display nudity or offend traditional notions of decency. France and Germany prohibit comparative advertisements in which one brand claims to be superior to another.

The modern marketplace abounds with products that pose difficult challenges for regulators. Consider the example of tobacco and alcohol. These products can be harmful or dangerous, but many people nonetheless desire to consume them. Most Western countries have decided that it is counterproductive to outlaw the sale of tobacco and alcohol, as doing so may create a black market and stimulate organized crime. The official response of most governments has been to allow the sale of such products but to prohibit or strictly constrain their advertising. Other product categories that tend to be governed by specific advertising regulations include pharmaceuticals and financial products.

Many products have positive uses but can also be dangerous if misused, like automobiles, knives, razors, lighter fluid, pesticides, toys, athletic equipment, and so on. In such cases, the law usually prohibits advertising that encourages the consumer to use the product in a dangerous fashion. Another common type of marketing regulation is one that prohibits advertisements from making false, deceptive, or misleading claims. In most countries, such rules are enforced by the ministry for consumer affairs. In the United States, rules against deceptive advertisements are promulgated and enforced by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

There are certain product categories in which exaggerated claims are commonly made. For example, in the case of skin creams, cosmetics, perfumes, deodorants, toothpaste, mouthwash, and so on, advertisers typically claim (or suggest indirectly) that their products make the consumer more physically attractive, especially to the opposite sex. The problem is that some consumers may not be sophisticated enough to discern the difference between innocent puffery and claims of effectiveness. Thus, teenage boys have been known to douse themselves with Unilever’s Axe deodorant products in the hope that they will attract females as effectively as is suggested in Axe’s notoriously provocative advertising. Many advertisements for such products come so close to making deceptive appeals that they may trigger the FTC’s attention. As a result, advertisers have learned to be cautious in the precise wording of their claims. For example, advertisements for skin cream may permissibly suggest that the user’s skin will “look and feel better” after use of the product, but they cannot include text guaranteeing the disappearance of wrinkles.

In many countries, regulators are especially vigilant when it comes to advertising aimed at children, because it is felt that children are sometimes more susceptible to manipulation or suggestion and are less likely to understand the dangers associated with the use of an advertised product. In Greece, for example, toy advertisements are prohibited between the hours of 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. In Sweden and Norway, all advertising aimed at children is prohibited, and in France, a child may not appear as the spokesperson in a commercial. In Holland, advertisements for sweets must include a toothbrush at the bottom of the ad to remind children to brush their teeth after eating sweets.

In this chapter, we will begin with a review of the advertising industry’s “self-regulation” of objectionable or unethical advertising. Many advertisements and marketing tactics fall into a regulatory gray area, where the advertisement is technically legal but still manages to offend some of the population. A frequent cause of such offense is the advertiser’s quest to develop a humorous or surprising advertisement. For example, one Danish advertisement featured an image of the Pope wearing a particular brand of sneakers, which offended many Catholics. In Italy, the fashion company Benetton shocked the nation by using an advertisement in which a priest is seen kissing a nun. In cases like these, it is not possible to make the advertisements illegal, but advertising industry associations feel it is necessary nonetheless to police the market for objectionable advertisements.

Our chapter-ending case study will deal with the ethical dilemma faced by executives at an advertising consultancy that is considering accepting an account for a global brand that manufactures skin-whitening products. The CEO of our company will call upon us to consider and debate the pros and cons of developing a US advertising campaign for Fair and Lovely, an Indian brand. In the United States, this product is demanded primarily by immigrants from South Asian countries, a large and growing demographic.

Many people feel that advertisements for such products contain racist appeals, since they are implicitly based on promoting the superiority of white skin. Is it ethical to market and promote such a product? Why or why not? Let us first consider some background to allow us to answer these questions.

Principles of Marketing Ethics

As stated earlier, every country has a basic framework of advertising law. Many types of advertisement are simply prohibited by law. However, with respect to advertisements that are legal but morally questionable (or otherwise objectionable), the advertising sector polices itself by applying self-regulatory codes of marketing and advertising ethics. This means that the advertising industry sets up its own committees to police questionable advertisements. Virtually every country has at least one advertising industry trade association with a self-regulatory panel or committee that reviews consumer complaints. After examining the advertisement in question, the panel decides whether or not to ask the advertiser to remove the advertisement; although advertisers are not legally obliged to follow the decisions of such committees, they usually do.

The self-regulatory panels base their decisions on ethical principles contained in codes of advertising ethics. The most influential codes are those established by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC); ICC Codes are followed by advertising bodies in over 30 countries. The ICC Codes are based on the core principles of legality, decency, honesty, and truthfulness in all marketing communications. The ICC further emphasizes that “all marketing communications should be prepared with a due sense of social and professional responsibility and should conform to the principles of fair competition, as generally accepted in business. No communication should be such as to impair public confidence in marketing.”

Self-regulatory codes are deliberately framed in general terms, because it can be very difficult to objectively define what kind of advertisement can be considered “decent.” It is assumed that standards of decency vary on a national or cultural basis, and in addition are likely to change over time. Thus, the ICC Code thus provides general guidelines: “Marketing communications should not contain statements or audio or visual treatments which offend standards of decency currently prevailing in the country and culture concerned.”

The ICC Code further stipulates the following:3

- Marketing communications should be so framed as not to abuse the trust of consumers or exploit their lack of experience or knowledge. Relevant factors likely to affect consumers’ decisions should be communicated in such a way and at such a time that consumers can take them into account.

- Marketing communications should respect human dignity and should not incite or condone any form of discrimination, including that based upon race, national origin, religion, gender, age, disability, or sexual orientation.

- Marketing communications should not without justifiable reason play on fear or exploit misfortune or suffering.

- Marketing communications should not appear to condone or incite violent, unlawful, or antisocial behavior.

- Marketing communications should not play on superstition.

Examples of Objectionable Advertising

Discriminatory Advertisements

As we review the history of advertising, we will observe that certain ads and campaigns were previously considered acceptable, and even popular, but today would generally be regarded as objectionable (in clear violation of one or more of the principles outlined above). Such cases can help illustrate the ongoing evolution of community standards in marketing ethics.

Consider the vintage ad for Schlitz beer in Figure 6.2. A suit-clad husband is comforting his tearful wife, who has just burned the evening’s dinner. The advertising copy reads as follows: “Don’t worry, darling, you didn’t burn the beer.” This advertisement appears to be aimed at men and contains a mocking and patronizing reference to young housewives of the day. In its time, such an advertisement was probably considered by many to represent light-hearted humor, but today it would be considered offensive by many viewers. The unstated implication is that men are breadwinners while women are weepy and emotional homemakers. By contemporary standards, the Schlitz ad is overtly sexist.

While it might seem that such advertisements are relics of the past, controversial discriminatory appeals and references continue to appear in the media. As a further example, consider the advertisement for the Mountain Dew soft-drink in Figure 6.3:4

Mountain Dew had run a successful series of edgy commercials targeted at Internet viewers and users of social media (an increasingly popular tactic). Perhaps influenced by the remarkable success of insurance company GEICO’s advertising mascot (a green gecko with a cockney accent), Mountain Dew had created a series of ads featuring a goat with a crazed passion for the caffeine-laced green soda. For one of these commercials, Mountain Dew hired hip-hop artist Tyler the Creator to create and produce the advertisement. In the ad in question, the goat is driving a car and is pulled over and arrested by a policeman. In flashback, we see the goat attacking a woman to wrench away her bottle of Mountain Dew, leaving the woman bloodied and wounded. In the next scene, the woman tries to identify her assailant from a police line-up that features the goat and four black men. Drinking steadily from a bottle of Mountain Dew, the policeman prods the woman to make a choice. The goat responds to the situation by speaking in a parodic hip-hop style, employing slang phrases such as “do her up” and “ya better not snitch on a playa.” Meanwhile, the Dew-amped policeman urges the woman to “nail this little sucker” and suggests it is “the one with the doo-rag.”

In retrospect, one wonders how such an offensive advertisement could have been released by a subsidiary of one of the world’s largest marketing organizations (Mountain Dew is a PepsiCo subsidiary). There was a great deal of outrage voiced when the ad was posted on Mountain Dew’s music/arts website. One college professor labeled the commercial as “arguably the most racist commercial in history.” The ad was promptly pulled and PepsiCo accepted full responsibility and apologized. To no avail, PepsiCo had pointed out that Tyler was African-American and that the four black men featured in the lineup were actually his close friends. Apparently, the irony intended by Tyler was meant to mock racism and discriminatory police practices. However, as many other advertisers had learned before, humor is a two-edged sword in advertising. It can attract attention, but it can also be misunderstood and cause offense.

Encouraging Harmful or Dangerous Practices

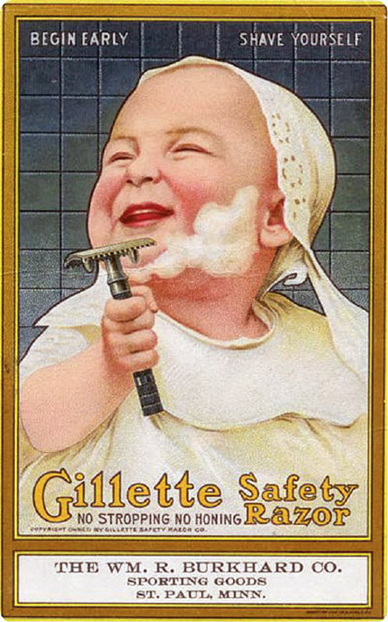

The advertisement in Figure 6.4 illustrates two categories of advertising that merit special scrutiny: advertisements featuring children and advertisements encouraging misuse of a product. Would any parent think it appropriate to have his or her infant shave himself with a razor? Of course not, but clearly that was not the intent of the advertiser.

The ad is attempting to be humorous by employing an absurd image, a baby shaving itself. The ad is also trying to make the point that the new Gillette safety razor is so safe that even a baby could use it without harm. There also may have been an intention to create an association between the smoothness of a baby’s skin and the closeness of the shave provided by the razor. By today’s standards, however, the advertisement appears reckless. While it is not possible that a baby would be influenced by an advertisement, it is not inconceivable that a small child of five or six years of age might be encouraged by this advertisement to play with a razor: The baby seems to be having such fun, and the small child might have seen his or her father shaving. Regardless of the likelihood that the advertisement could cause harm, today’s advertisers have become increasingly wary of using advertising that features children engaged in dangerous activities.

Potentially Dangerous Products: Advertising Bans and Restrictions

As stated above, there are products that are sold legally but that are considered to have such a high potential for harm or abuse such that their advertising has been banned or regulated. Let us consider just two such product areas: cigarettes and alcoholic beverages.

Cigarettes

Concerned with medical research that revealed the health hazards of smoking, the US and European governments began to regulate tobacco advertising in the 1960s. The print ad in Figure 6.5, from 1962, features an idyllic family scene that suggests that a smoker gets “lots more” from a particular brand. The ad suggests that one acceptable way to enjoy the smoking experience is to smoke in the company of one’s spouse and children. In 1964, however, the US Surgeon General issued a formal report that concluded that smoking caused lung cancer and chronic bronchitis. This led to the government instituting a series of regulations aimed at the tobacco industry. The new laws required health warning labels on all cigarette packages and required that all cigarette companies file annual reports to the FTC. One goal of these regulations was to oblige the large tobacco companies to disclose their advertising expenditures and strategies, so that the government would be able to assess the link between tobacco advertising and smoking-related health risks.

Throughout the late 1960s, the US government accumulated and analyzed data on the marketing and advertising practices of the large cigarette companies and finally concluded that tobacco advertising encouraged smoking. As a result, the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act was passed and signed into law in 1970. This act banned all cigarette advertising on television and radio advertising in the United States. At the time the prohibition went into effect, tobacco companies were spending eighty percent of their advertising budgets on television advertising, so the impact of the law was significant.

Subsequently, the United States enacted further restrictions on cigarette advertising. In 1999, billboard advertising of tobacco products was banned. In 2010, tobacco companies were prohibited from sponsoring athletic, musical, or artistic events, and from featuring their logos on apparel. However, the government has stopped short of banning print advertising. These governmental efforts have been matched by a certain level of self-regulation on the part of tobacco companies. For example, after a public outcry over its use of a cartoonish camel to sell cigarettes (it was feared that such advertising would be appealing to children and teenagers), Camel Cigarettes voluntarily stopped advertising in magazines in 2007. However, in 2013 Camel resumed its practice of advertising in magazines.

Alcohol

Alcohol has been classified by the International Agency on Research for Cancer (IARC) as a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning that the circumstances in which humans are exposed to alcohol are sufficient to create a risk of cancer. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), alcohol causes approximately 1.8 million deaths per year. In the United States alone, approximately 10,000 deaths per year are the result of automobile accidents caused by drunk driving. Despite these sobering statistics, the US government has taken a very different approach to alcohol advertising as compared with tobacco advertising. In essence, the FTC has primarily asked the alcohol industry to self-regulate.

Given that advertising is known to be an effective means of increasing sales and market share, why would alcoholic beverage companies agree to abide by self-regulation? Here, the example of advertising bans on tobacco products is instructive. Other industries whose products are seen as controversial have been influenced by the threat of an advertising ban similar to that placed on tobacco products. Consequently, trade associations for such industries have sought to maintain an open dialogue with legislators in the hope of appeasing them with effective self-regulation, so as not to be faced with a total ban. In the United States, the self-regulatory focus has been to minimize the exposure of underage drinkers to the advertising of alcoholic beverages. Currently, the alcoholic beverage industry has agreed to restrict advertising in print, TV, and radio to those venues where studies show that more than 70% of viewers will be of drinking age (i.e., older than 21). Further, the industry has agreed to support a public campaign against underage drinking and to include warnings about drinking responsibly in all advertising. The FTC has urged industry to apply the 70% rule to sponsorship of musical and sporting events as well but no agreement has been reached.

Even with these self-regulatory measures in place, there remains a good deal of concern among watchdog groups about the appeal of TV advertising to young people, who are considered more likely to abuse alcohol than older viewers. Moreover, the alcohol industry continues to employ advertising appeals based on the implicit sexual allure of drinking in bars or at parties. This approach is disturbing to industry critics who see the glamorizing and sexualizing of alcohol consumption as another way of attracting young people to alcohol products. As with cigarettes, the implicit threat is that if the industry can get young people “hooked” early in life, then they will become lifelong consumers of a product with known health risks. Youths who begin drinking at age 15 are four times more likely to become alcoholics than those who begin drinking at age 21.5

Case Study: The Marketing of Skin-Whitening Creams

Americans—in particular, white Americans—spend hours in tanning salons going to great efforts (and sometimes even incurring great pain and health risks) to make their skin darker. In other parts of the world, such as the Caribbean, Africa, East Asia, and the Indian sub-continent, people go to much expense to lighten their skin. They do so through the purchase and application of skin-whitening or skin-lightening creams that purport to make dark skin lighter. (Whether or not they actually work is controversial.) In many of these regions, lighter skin is more highly regarded socially. Arguably, this phenomenon is a sad by-product of colonialism, in that it is based on a positive association with the skin color of Caucasians. The flip-side is that, in the United States and Europe, darker skin is often considered attractive and exotic.

Fair and Lovely is an Indian brand of skin-whitening products manufactured and marketed by Hindustan Lever Ltd. (HLL). Fair and Lovely is the top-selling skin-whitening brand in India, followed closely by Fairever which is made by CavinKare. HLL advertising touts Fair and Lovely as a “miracle worker” and claims that it is “proven to deliver one to three shades of change.” As a result of competition from Fairever, HLL stepped up its marketing efforts in recent years, which led to a great deal of controversy. One of the controversial HLL ad campaigns was based on the theme “The fairer girl gets the boy.”

In one of the typical television commercials used in this campaign, a poor father is lamenting the fact that he does not have a son who can work and help support the family. His daughter, who has dark skin, looks on and clearly feels a sense of guilt. When she seeks employment, she is rebuffed because of her dark skin. Her unhappy lot is magically transformed with the use of Fair and Lovely skin-whitening cream. Suddenly, she not only appears to have much lighter skin, but the other characters in the commercial perceive her as much more beautiful. She dons a miniskirt and finds employment as a flight attendant, receiving the romantic attention of a fair-skinned Westerner. Among the many improbable benefits associated with use of Fair and Lovely, it seems, are a wardrobe change, secure employment, and a foreign boyfriend. The newly confident young woman is now a success and can take her proud father out for a lavish dinner.

The popularity of Fair and Lovely, as well as other skin-whitening creams, is tied to Indian cultural traditions. Lighter skin has been associated with a higher caste and therefore greater social status. Most of the famous female stars in India’s popular Bollywood movie industry are light-skinned. Do the Fair and Lovely products—or those of competitors—really make someone’s skin lighter? Or is this idea just an illusion perpetuated by effective advertising? In its official documentation regarding Fair and Lovely, HLL only states that the cream contains vitamins essential to skin care and UV blocking agents (as in sunscreens). In other words, rather than actually turning the skin lighter, Fair and Lovely may only work by keeping skin from getting darker, something likely to happen in sun-drenched areas of India. Critics claim that at best such products temporarily bleach skin lighter.

Not everyone in India is comfortable with the promotion of skin-whitening creams. A number of groups have come out against HLL and Fair and Lovely, charging the company with deceptive advertising and the promotion of discrimination and sexism. Many critics point out that the celebration of lighter skin is implicitly a rejection of darker skin. Thus, the Women of Worth Foundation launched a campaign called “Dark is Beautiful” to protest skin-whitening products.

Indian fashion writer Rumnique Nannar observed the following:

I’ve heard the stray dig “for a Punjabi, you’re quite dark” or jokingly mentioned, “are you sure you haven’t been adopted from Kerala?” or even the infamous, “wow, you are, like, so exotic”—all standard fare for me as the darker blip in family photos. Having your identity reduced to skin tone can be crushing, particularly when it doesn’t fit with the more fair ideal admired by most cultures. In India, ads by Emami and Fair and Lovely often seemed laughable and pompous to me, with grandfathers sanctioning the use of skin lightening creams to ensure the success and subsequent beauty of their dusky daughters.6

Nannar points out that to be identified or even judged according to one’s skin color is demeaning and diminishes a woman’s self-esteem and creates a sense of insecurity.

Topic for Debate: Should an American Advertising Agency Represent Fair and Lovely?

In this fictional case, a small but highly successful new advertising agency based in New York City, Enviralism, Inc., has become known for its ability to craft effective social media campaigns targeting the so-called millennial generation (young people born between the early 1980s and early 2000s). Enviralism has become successful especially with rapidly growing high-tech, fashion, and communications groups. This small agency is known for its cutting-edge creativity.

The CEO of Enviralism, Ralph Rodriguez, has been approached by Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods conglomerates, with a US advertising budget in the tens of millions, to craft a strategy for marketing Fair and Lovely products to South Asian and East Asian immigrants and their first-generation children. Unilever is aware of the controversies surrounding Fair and Lovely products, but is also aware that there is a significant US market for skin-whitening products. As a result, Unilever would like to tap into Enviralism’s knack for thinking up unusual, outside-the-box marketing strategies. In its initial discussions, Unilever has talked about starting with an annual $2 million budget, which might be doubled or tripled in subsequent years. This would instantly make Unilever the largest client at Enviralism, which is still a very small boutique agency with only 18 employees.

However, when Rodriguez discusses the opportunity with his Creative Director, Elaine Williams, she demurs: “That’s a straight-up racist product, Ralph. We can’t go there, no matter how much money it makes us.”

Ralph, who has just invested $200,000 in renovating a Williamsburg loft into beautiful new offices for Enviralism (complete with state-of-the-art computer and graphics equipment), is not so sure.

He counters, “What about Coppertone? What about Hawaiian Tropic? Those products make people’s skin darker, supposedly, but nobody complains. What about Afro Sheen and other hair-straighteners for the black community? Nobody says those are racist. This is a $500 million market in India alone, not to mention a standard skin-care product category in Japan, China, Indonesia, and Thailand—we’re talking about a market with well over two and a half billion people!”

Ralph can see that Elaine is not convinced, so he schedules a board meeting where his top executives will argue the case, pro and con, for accepting the Unilever account. You will be assigned to one of those teams. Should Enviralism agree to craft advertising campaigns for the Fair and Lovely product line?

Affirmative

Enviralism should agree to represent Fair and Lovely in the United States.

Possible Arguments

- We have a responsibility to customers to provide them with the products they desire; we should not demean our customers by treating them like children.

- Fair and Lovely is not dangerous and may provide psychological benefits to customers, like other cosmetics products.

- Fair and Lovely’s skin enrichment, sun blocking, and moisturizing features are beneficial.

Negative

Enviralism should refuse to represent Fair and Lovely.

Possible Arguments

- Fair and Lovely is an ineffective product and its related advertising claims are therefore deceptive.

- Fair and Lovely promotes and sustains social, racial, and ethnic stereotypes and prejudices.

- Marketing Fair and Lovely would be socially irresponsible.

Readings

6.1 “Whiter-Skin Ad Campaign Spurs Debate Among Thais”

Chomchuen, Warangkana. “Whiter-Skin Ad Campaign Spurs Debate Among Thais.” Wall Street Journal. October 25, 2013. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304799404579157422770231930.

6.2 “Skin Whitener Advertisements Labeled Racist”

Sidner, Sara. “Skin Whitener Advertisements Labeled Racist.” CNN. September 9, 2009. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/asiapcf/09/09/india.skin/#cnnSTCText

6.3 The Dark Side of Skin-Whitening Cream

Hundal, Sunny. “The Dark Side of Skin-Whitening Cream: The Dangerous Fashion for Skin-Whitening across Asia Perpetuates Racism and Should be Stigmatized as Such.” The Guardian. April 1, 2010. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/apr/01/skin-whitening-death-thailand/print.

Synthesis Questions

- Is there anything wrong in marketing cosmetics products with the suggestion that they make the buyer more beautiful, even if this is unrealistic in many cases?

- Should skin-whitening products be legal? Why or why not?

- Does modern society have too much advertising? How could we control it? Can you suggest any specific mechanisms or regulations that should be implemented?

Endnotes

1. “Magna Global 2013 Advertising Market Forecast,” Magna Global, accessed October 23, 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20141026034607/http://news.magnaglobal.com/magna-global/press-releases/advertising-growth-2013.print.

2. For example, the article “Anywhere the Eye Can See, It’s Likely to See an Ad,” (New York Times, January 15, 2007), quotes figures ranging from 2,000 to 5,000 per day. Advertising industry sources argue that the number is much smaller, commonly around 300 per day.

3. “ICC Code of Consolidated Advertising and Marketing Practice,” International Chamber of Commerce (2011), accessed December 2, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20220715073216/https://www.codescentre.com/aboutyou-3/.

4.The commercial can be viewed on YouTube via the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=MdFRWf-CNC8

5. AAFP, “Alcohol Advertising and Youth” (Position Paper), American Academy of Family Physicians, accessed October 25, 2013, http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/alcohol-advertising.html.

6. Rumnique Nannar, “Is Dark Beautiful? The Fairness Debate Opens Wide in India,” Huffington Post, August 26, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/jugni-style/is-dark-beautiful-the-fai_b_3793257.html.