Chapter 7: Mid-Term Evaluation: A Case Study: Building a Better York Policy

Abstract

This case study examines the policy development associated with the rejuvenation of the City of York, Pennsylvania between 2003 and 2010. This is a review of York’s history with the culmination of race riots in the summer of 1968 and 1969 that are recognized as the riots of 1969. The discussion is critical of a single source strategy such as COMPSTAT that is unable to serve as a standalone Community Oriented or Problem Oriented Policing strategy. Specifically, COMPSTAT is a significant strategy but without other programs or strategies simultaneously administered, COMPSTAT may be an exercise in futility. The evaluation of the York plan describes a multi-facet approach of policy development of “total community” providing examples of Community Oriented and Problem Oriented Policing along with collaboration of government, quasi-government and community. Albeit this is a multi-facet approach it also crosses numerous ethical foundations. The study serves as a review of the COMPSTAT Model and its’ utility in the City of York police and community setting to develop complete community. Finally, the case study foundation resides in data use, interviews and literature review of materials related to the York’s history relating to policy development. Such as programs initiated to alleviate crime and obviate the tensions realized in the 60’s, and the observations of community leaders that have both a hereditary and national perspective of the right fix and in the right quantity; and what has happened on a more global framework that has been useful in York, Pennsylvania.

Introduction to the study

Statement of Purpose

This discussion reviews the amalgamation of multi-governmental agencies and quasi-governmental agencies with unlikely partners such as landlords, job training providers, neighborhood groups, philanthropic, public and private resources, education systems and the police demonstrating true community policing must encompass several strategies under the philosophical tent of community policing to be effective. The study posits that community and problem-solving policing is a general philosophy (attitude modification) that must be borne by all stakeholders of a community while at the same time engaging in multi-facet strategies as discussed herein. Attitude modification is successful base upon top down and bottom up decision making from all strata of the community. This is a discussion of York, PA however it is further asserted that the strategies discussed when employed in other communities will work with sufficient alteration fitting the needs of that community.

Historical Perspective

York became home for America’s forefathers during the American Revolution for the period of English occupancy in Philadelphia after the start of the Revolutionary War. The Articles of Confederation were crafted and adopted in York during the period that America’s leaders had fled Philadelphia and had taken refuge in the wilderness. York, PA was west of the Susquehanna River which was commonly thought to be wilderness at this juncture in American history. The document itself was not successful but did play a significant role as a forbearer of the United States Constitution and America’s individual liberties. York is in a beautiful geographical area, west of the Susquehanna River, close to major cities of the Eastern Seaboard, near the Chesapeake Bay, but also not far from the majestic Appalachian Mountains. The city is intersected by Interstate 83 (Harrisburg, PA to Baltimore, MD) north to south and U.S. Route 30 equidistant between Lancaster, PA on the east and Gettysburg, PA on the west. Once a flourishing industrial mecca, York is now saddled with rusting hulls of iron once manufacturing monasteries situated on environmentally unsound earth and economic uncertainty due to decreasing resources.

Analysis of the social, political, legal, and economic forces that influenced the development and emergence of the policy

Problem Statement

York experienced decades of racial tension, culminating in the 1969 Riots. The causal factors of the 69 riots in York have been identified as: poor housing; jobs; education; poverty; and police abuse toward Blacks and with the blessing of the white in the community. These issues are described and discussed in a pre-riot and post-riot format indicating what was and what has been accomplished in order to prevent the event from reoccurring in York (Kalish, 2000).

The political atmosphere preceding and during this period was one of oblivion and denial, rather than confrontation of the issues of poor housing, education and employment opportunities for Black residents; much like American society of the same period. Kalish (2000) asserts “The triggers for the riots were the city’s refusal to provide recreation programs and facilities in Black neighborhoods, refusal to enforce housing codes that affected the living conditions of Blacks, the unwarranted use of police power and the arrogance of the mayor and other community leaders” (p.72). Further highlighting the lack of policy or themes relating to race, culture and the public safety is revealed in the Investigatory Hearings into Causes of Racial Tension in York, Pennsylvania. Human Relations Commission finds York has high potential for violence due to either the inability or unwillingness on the part of the community and local government to address the grievances of the Negro residents (as cited by Kalish, 2000, Chapter 4).

The remnants of a 1969 race riot were only recently resolved in criminal trials in 2001 and 2002 convicting four persons after trial and accepting pleas from four others in exchange for their testimony. The convictions were for the murders of one black female (Lillie Belle Allen) and one white police officer (Officer Henry Schadd); one of the accused and ultimately acquitted after a nationally recognized trial, was Mayor Charlie Robertson who at the time of the riots was a York City Police Officer accused of providing bullets to white gang members.

Robertson was elected to the school board in 1975 (Bunch, 2001). He first ran for mayor in 1993, was re-elected in 1997, and was again running in 2001 when he was indicted for Murder during the 1969 Riots. Robertson was aware of the pending Grand Jury Investigation but sought a third term in 2001, and had won a tight race in the Democratic primary against city councilman Ray Crenshaw. Within two days of the election results legal charges were brought and Robertson was arrested and put in handcuffs (Cline, 2001 and Bunch, 2001). Crenshaw was the first black man to have run for mayor of York (Cline, 2001). Robertson was reluctant to withdraw from the Mayoral race but gave way through pressure by political supporters convinced him to do so “for the betterment of York”(Bunch, 2001). Fellow Democrat John S. Brenner was ultimately elected as the next mayor. He took office in 2002 and subsequently hired Mark Whitman as his Police Commissioner.

The required healing process laid in wait for nearly forty years and what must be determined if it is too late to heal (Longman, 2001; Lueck, 2002; & New York Times, 2002).

Reviewing discussions of race and change since the 1950’s offered by Ore (2009) appears appropriate when drawing a comparison with television sitcoms, “The five decades can be summed up in the French Phrase, Plus change, plus c’est la meme chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same)” (p. 460). The political, neighborhood, and economic leaders required new policy to break the status quo and usher in the new millennium. Mayor John Brenner, (Personal Interview, 2011) alludes to the healing process of York and improvements of relationships are based on attitude and the conduct of government.

Community Oriented Policing and Problem Oriented Policing (COP/POP) strategies became the policy of the day. In order to address concerns of racial profiling and police misuse of authority the York City Police Force designed programs meeting community needs while being sensitive to its residents was the policy of Mayor John Brenner; to name a few Nuisance Abatement, Clean Sweeps, Neighborhood Enforcement Units, Curfew Center and Civil Enforcement Units, availability of the Police Commissioner at neighborhood meetings, access to crime information on daily basis and police officers becoming more approachable. The mission of York’s Community Policing Model is to preserve neighborhoods by reducing crime and eliminating the fear of crime by increased attention to quality of life issues and equality in enforcement for all residence Advance strategies that promote neighborhood stability and livability; Encourage positive activity and behaviors that contribute to a higher quality of life in the community; Eliminate community nuisance and crime problems such as public intoxication, abandoned buildings and vehicles, open drug markets and drug houses, prostitution, public gambling, loitering, nuisance dogs, loud music and unacceptable levels of garbage, litter and waste materials on the property; Identify critical leverage points that if eliminated, diminished and/or disrupted will result in an environment where serious crime cannot flourish, close down properties with code violations; Develop and expand the number and range of strategies that are most effective at fighting quality of life crimes and abating long-term illegal conduct; and Prosecute civil code violations such as noise abatement, rigorously enforce padlock and forfeiture cases to maintain community standards and address crime problems.

Policy Influences

Present in executive decision making relative to policy making is both internal and external variables. According to Marion & Oliver (2012) “Mayors in recent years have been instrumental in the implementation of community policing with cities and towns across the United States. In many cases the ability to implement such a program begins with the hiring of a new chief and the mayor giving that chief a specific charge” (p.123). This was the case in 2003 with the hiring of new Police Commissioner that was similarly situated in ideology as was the Mayor. The COP/POP experience in York, PA was influenced by economics and the community pressure brought to bear; but more difficult to deal with for the Police Commissioner was the resistance to change and peer pressure from within the rank and file members of the police department and neighborhoods as well.

Research suggests that local governments were more likely to commit to the needs of the community than did federal officials. Furthermore, federal officials reacted toward cities based on ideology rather than need (Choi, Turner, & Volden 2002). Whenever an election was needed in a city which had a mayor-council, grants were requested in the short term due to the beneficial impacts that they often have (Choi, Turner, & Volden 2002). However, York City was financially distressed due to shrinking tax base and being the County Seat, nearly 45% of the properties were tax exempt; therefore, became more reliant upon outside resources to address the crime issue. Second to the financial difficulty of the City was impacts by a heavily unionized police department which felt threatened by the political mechanism and feelings of indifference toward the members attempting to provide a service to the City. At the same time the community at large and certain segments of the community felt neglected by the police and was of the mind-set, crime was ok in their part of town.

Community policing style or strategies is unique to its own environment but police remain with the responsibility of enforcing the law and making arrest, which could conflict with the inter-departmental relationships between police officers and community partners (Smith, Novak, & Frank, 2001). As it relates to intra-department relationships police officers engaged in Community Oriented Policing techniques and strategies may engage in traditional police activities to satisfy their peers. Additionally, research has shown that a subculture which embraces group solidarity among the police can lead to violations of community oriented policing practices (Smith et al., 2001).

Officer discretion has become an issue in community-oriented policing. Direct and constant contact with the public can lead to abuses by officers (Weisburd, & Eck 2004). Officers could be encouraged by the public to use methods outside of their training to handle the problems that the public faces (Weisburd, & Eck 2004). Community policing places a high value on the responsiveness by police to the community needs. Arguments by opponents of COP/POP state that community policing will weaken the rule of law by the expanded use of discretion that may come from the implementation of community policing (Weisburd, & Eck 2004). Research has shown that officers rely on policing for various reasons one in which is the social activities. As a result of social bonding police are more likely to be persuaded by peers to engage in traditional police methods rather community-oriented methods (Smith, Novak, & Frank 2001). However, community police officers respond to calls voluntarily in their district to prove legitimate among peers and have a sincere pride in doing “police work” (Smith, Novak, & Frank 2001).

Therein lays the crux of the issue for the new Police Commissioner; recrafting attitudes and developing community as part of the policing philosophies and policy. Executive policy development may look good on paper but often is not worth the paper it is written upon unless buy-in is obtained from a grassroots inception. Policy development in this situation required input from the officers performing the daily tasks of policing and restructuring management philosophies that may embrace a new direction. This is discussed in greater detail in the explanation of strategies that were developed inside the community.

Community Policing and Problem Oriented Policing-Defined

Community Oriented Policing (COP) and Problem Oriented Policing COP) burst onto the police scene, primarily in the New York City Police Department in 1990’s touted as the “silver bullet” for addressing crime issues in the Big Apple. Community Policing was in place in many police organizations well before this, but under the guise of community service; particularly in smaller police agencies (10-25 sworn members). The increased crime notoriety and attention garnered in major cities added expediency to the issue of addressing crime in a more effective and efficient fashion; ergo the Community Oriented and Community Policing philosophies gained prominence among policy makers.

What is COP and POP? And why does it deserve attention? These are often misunderstood and considered strategies rather than as a philosophy that focuses on the way that departments are organized and managed and how the infrastructure can be changed to support the philosophical shift that may support community policing. They are both defined as a philosophy but COP is designed to build partnerships within the community that are helpful to resolve issues and problems (Goldstein, 2001 cited by Choi, Turner, & Volden, 2002). Whereas POP is a management strategy that further breaks disorder, disruption, criminal activity and criminal enterprise into more microscopic units for examination. POP utilizes crime data analysis, community input and police officer experience to develop a strategic and systemic approach to resolving the issues impacting quality of life. POP is generally employed for purpose of finality rather than simply relocating the problem. Both philosophies (strategies incorporated) place greater value on prevention through public and private collaborations for the sole purpose of increasing the quality of life while reducing crime and the fear of crime. Most often these are employed through robust strategies with a commitment to implement long-term strategy, rigorously evaluating its effectiveness, and, subsequently, reporting the results in ways that will benefit other police agencies and that will ultimately contribute to building a body of knowledge that supports the further professionalization of the police (Goldstein, 2001 cited by Choi et al., 2002).

Multi-Facet Policing Strategies Employed in York, Pennsylvania

Community and Problem Oriented Policy

Since the unrest of the 60’s in the United States the need for police/community collaboration was never more evident than in York, PA. The need for community-oriented policing (COP) and problem-oriented policing (POP) was not only needed but was in demand. However as in most government initiatives, resources were not readily available. An individual component of COP/POP Philosophy is the data driven information derived from community data files. Discussed as a single strategy in most situations is COMPSTAT. COMPSTAT is a statistical measure of crime used in forecasting crime and supports innovative strategies to combat future crime. Strategies commonly deal with quality of life issues, and community orchestrated programs to prevent further debilitation of neighborhoods; however, they should not be confused as standalone strategies with any efficiencies. These strategies are ineffective unless in collaboration with each other or other strategies provided as examples in this historical review of York City.

Did the need for COP/POP exist in York, PA? Mr. Bobby Simpson, Director of Crispus Attucks (Appendices C) of York (personal communication, 2011) likened the York City Police Force of the 1950’s, 1960’s and 1970’s to those of Alabama during the Countries racial crisis. The police brutality was insidious, pervasive and had the blessing of the white community, the media at the time, and the business community. Ore (2009) maintains “This governing class maintains and manages our political and economic structures in such a way that these structures continue to yield an amazing proportion of our wealth to minuscule upper class” (p. 94). The G.I. Bill after World War II, as it relates to educational benefits, may be classified as affirmative action programs for white males because they were not extended to African Americans or women of any race (Ore, 2009). Mr. Simpson, Director of Crispus Attucks, contends that although problems remain today, overall things have improved in the City of York (personal communications, 2011).

Much of the black population considered police hostile to minorities. Police were poorly trained particularly in coping with civil disturbances. Police lacked policies dealing with canines, firearms and chemicals and The York City administration rigidly adhered to a policy of preservation of status quo and the exclusion of non-whites from policy making (PA Human Relations Commission, 1968). Mayor John Brenner issued his direction to address these and other policing policies as previously stated. The Mayor directed as part of the overarching approach of securing a greater quality of life in York is that of COP/POP policy and required the York City Police Department to devise and implement programs consistent with the needs of the community.

The police policies required triangulated data using neighborhood input, local crime data, and useable intelligence in cooperation with educational systems, job training, and neighborhood restoration projects to rejuvenate York City. In particular, local data should be the most reliable, current data, and used in an efficient manner that may produce efficiencies otherwise left to chance. COMPSTAT (Computerized Statistics) a nationally recognized program originally introduced in New York City is a strategic problem-solving system that combines “state-of-the art management principles with cutting-edge crime analysis and geographic systems technology” (Willis, Mastrofski, & Weisburd, 2004).

A COMPSTAT program has as its explicit purpose to help police departments fight crime and improve the quality of life in their communities. This is achieved by overcoming traditional bureaucratic irrationalities, such as loss of focus on reducing crime, department fragmentation, and lack of cooperation between units because of “red tape” and turf battles, and lack of timely data on which to base crime control strategies and to evaluate the strategies that are implemented (Weisburd, Mastrofski, McNally, Greenspan, & Willis, 2003).

A Problem Oriented Policing strategy that was found useful in New York City’s transition was that of the information produced by the COMPSTAT that was also used by the Police Commissioner to judge the performance of precinct commanders and by precinct commanders to hold their officers accountable. Unlike traditional police bureaucracies, the COMPSTAT is intended to make police organizations “more focused, knowledge-based, and agile” (Willis et al., 2004). COMPSTAT has proven itself, however it is posited here that COMPSTAT enacted without simultaneous strategies is nothing more than another single tool in the agency toolbox. COMPSTAT is a singular strategy that when used in concert with other COP/POP strategies will provide the intended results of efficiency and effectiveness addressing community problems and concerns. COMPSTAT as an inter-disciplinary research topic has significant impact on other criminal justice systems and one does not have to travel too far from NYPD to find such a study. A similar data collection and accountability was initiated in York City and was led by the Captain of Operations.

A similar COMPSTAT program is engineered by the New York City Department of Corrections that operates under the Total Efficiency Accountability Management Systems (TEAMS) (Horn, 2008). In addition to decreasing jail violence and improving the health and safety of the inmates TEAMS tracks data on more than 600 large and small aspects of the day-to-day life of the city’s jails. These aspects range from escapes and homicides to the number of inmates regularly attending religious services and the length of time inmates must wait before they are seen for medical care in the clinic. The Department measures the time it takes to process and house a newly admitted inmate and counts searches, contraband finds, days lost to sick leave, overtime, maintenance order backlogs and hundreds of other metrics. Knowing that information is management power; the Department even measures the cleanliness of its showers and toilets, and here too, data management and accountability have produced positive results (Horn, 2008).

Again, TEAMS is not a stand-alone proposition, but rather a strategy that is used in unison with other data/information, programs and strategies simultaneously. Management to line-officer accountability has demonstrated positive developments within the criminal justice field when used in concert with other adaptations for improvement.

Walsh and Vito (2004) contends that “COMPSTAT is a goal-oriented, strategic management process that uses information technology, operational strategy and managerial accountability to guide police operations…reduce crime and improve the quality of life” (p.57). Further bolstering the point that COMPSTAT cannot be successful without collaboration with other tactics it is asserted in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, four crime reduction principles that create the framework for the COMPSTAT process are: accurate and timely data; effective tactics; rapid deployment of personnel and resources; and relentless follow-up (Shane, 2004). Additionally, police have access to a closely associated by-product of the computer age, Crime Mapping, which is the implementation of geographic mapping of crime using these systems they link maps of the agency jurisdiction with other computerized police records and replaces the old pin maps (LaVigne and Wartell, 2000). Technology has advanced rapidly and continues to do so daily, however not all police agencies have access to either of these systems nor do they have the required resources required for implementation.

COMPSTAT is an important strategy for Community Oriented Policing and Problem Oriented Policing philosophy implementation. Although critical, COMPSTAT is not without critics who have cited the program as a method of stricter control over managers and line-officers in a police organization. In practice it appears that COMPSTAT, at least so far, is just another way—albeit one that employs advanced technology and different management principles—for police leadership to control mid-level managers (precinct commanders) and street-level police officers (Moore, 2003). COMPSTAT is important to both the COP/POP as it represents accurate, timely data critical to the decision making process, particularly during resource limited situations as is the City of York’s case.

Critics argue that COMPSTAT has had the opposite effect desired in an atmosphere of Community Policing. Rather than empowering line-officers to act independent of the bureaucracy, it has grieved the line-officer to an art form of submissiveness more fearful to act. COMPSTAT represents a sea change in managing police operations, and perhaps the most radical change in history (McDonald, 2004), but remains a single tool in the tool box of COP/POP. The question remains- “Have today’s law enforcement leaders-maintained pace with the technology and information highway, altered leadership styles accordingly to more efficiently manage the organization, and empowerment of those providing the service?”

Identification and analysis of the policy’s current outcomes and unanticipated consequences: Description of policy improvements or enhancements

York City Programs

COMPSTAT is a single strategy that is ineffective unless integrated with other programs such as nuisance abatement, civil enforcement, directed and targeted patrols (Figure 2.0-2.3, www.yorkcity.org). The following is a descriptive listing of programs York’s COMPSTAT strategy is interrelated:

Figure 2.0 Nuisance Abatement.

This program was enacted as a city ordinance; this legislation contains a host of civil and criminal activities that are considered nuisances. Drug sales, litter, excessive noise, barking dogs, unlawfully dealing with children, and disorderly bars are but a few of the topics contained in this law. Each violation carries with it a set number of points. When a property receives 12 points in a 6-month period, or 18 points in a 12-month period, both the property and business owners (where separate) are required to appear before an independent hearing officer. If the nuisance charge is sustained, the mayor has the authority to close the business for up to one year, and revoke all of the business owner’s certificates to operate a business within the city. Also, the property is posted with signs that declare the location a nuisance, as well the period of closure.

Figure 2.1 Neighborhood Enforcement.

Figure 2.2 Clean Sweep Details.

Figure 2.3 Curfew Center.

Housing Strategy: Partnerships in York, Pennsylvania

Deteriorating neighborhoods of crime, blight, poverty and poor housing is the typical “Broken Window” scenario. The City of York in its devising and implementing COP/POP strategies found an abundance of partnerships, one being The Ole-Town East Project. Jane Conover, (personal communications, 2011) V.P. of York County Community Foundation (formerly Program Coordinator of Ole Town East-Elm Street Project) emphasized several positive aspects in current housing situations.

The Elm Street Project is a state funded project (Elm Street Funding is the name of the State Funding Program Source) that began in 2004 with numerous partners and additional funding sources. During the program’s existence she notes the project has reduced criminal incidents by 39% (see policing section for programs used); made landlords more responsible and put some out of business; increased livability and quality of life in the designated area; broke down existing barriers; increased neighbor-to-neighbor visibility; increased membership in the neighborhood association; and the bringing together of a diverse neighborhood of African Americans, Hispanics, Gays and Lesbians, whites, and the elderly. (To emphasize this point, see Appendices A. – Ms. Betty’s Story.).

According to J. Conover (2011) she credits partnerships for reinventing the neighborhood due to the access of the Police Commissioner and Police Command (regular attending neighborhood meetings) and has not only increased home ownership but pre-housing crash, property values increased from $45,000 to $75,000 (Figure 1.0; 1.1 Olde Town East reported outcomes).

Figure 1.0 Olde Town East-Elm Street Project.

A total of 71% of the residents plan to stay in their home, an improvement from 68% in 2008 and 67% in 2007.The percentage of residents reporting that crime is not a problem in their neighborhood has steadily increased since 2007. Feelings of safety are at the highest levels they have been since the first surveys in 2005. The number of criminal incidents has declined by 39%.The average sales price for residential property has more than doubled since 2000.

Imperative to community success requires community support and partnerships, specifically when attempting to determine which fire to put out next. Hotspots or areas of high crime or high incidents of incivility as derived from police data information system- have generated substantial debate as to how they are identified, whether it should be by data only or police officer’s impressions (Hotspots, 2008).

Figure 1.1 Olde Town East-Elm Street Project.

| Project Component | Outcome | Target Completion Date | Progress This Period 1/30/09 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Develop a Sustainable Organization | 1) Five new residents become dues-paying members of the neighborhood association each year | 12/31/2005,06,07,08,09 | 19 residents became due paying members this period. |

| Improve Neighborhood Safety | 1) The average score on Quality of Life surveys conducted annually among residents increases by 5% each year

2) The annual number of reported criminal incidents declines by 10% (From 321 in 2003 to 289 in 2009) 3) The number of trees in the neighborhood increases by 50% from 148 to 300 by 2010 4) A park is developed in the 200 blocks of E. Princess & Prospect Streets |

06/01/2006,07,08,09

06/01/2006,07,08,09 12/31/2005,06,07,08,09 12/31/2006 |

1) The 2008 data shows that the overall quality of life index showed an improvement of 11 points (35%), from 32% to 43%.

2) Criminal incidents decreased by 25% b/w ’07-’08. 3) None this period 4) Park completed. |

| Improve Neighborhood Economy & Image | 1) The percentage of owner occupied housing units increases from 24% of total to 27% of total by 2010, an increase of about 36 units

2) The average number of days to sell a property in the neighborhood declines by 7 days (from 74 days to 67 days) by 2010 3) The average residential sales price increases by $5,000 from $26,988 in 2004 to $31,988 in 2010 4) The average household income increases by $5,000 from $24,557 in 2000 to $29,557 in 20105) The number of building permits issued for properties increases by 5% per year |

06/01/2010

06/01/2010 06/01/2010 06/01/2010 12/31/2005,06,07,08,09 |

1) None for this period.

2) The average number of days on the market increased by 5 days between 2007-2008 (from 65 to 70 days). 3) The average sales price decreased by $8,309.85 or 33% between 2007-2008. (from $68,135.95 to $45,826.10) 4) Interim census estimates showed no significant change between income in 2000 and estimated income in 2004. 5) In 2008, the number of building permits declined, but overall, building permits have doubled since 2001. |

| Improve Physical Environment | 1) The annual number of housing code complaints reported in the neighborhood decline by 20% by 2010

2) The vacancy rate among housing units decreases from 18% to 15% by 2010. |

12/31/2009

06/01/2010 |

1) There were 34 housing code violations reported in 2008, down by 13% since 2004.

2) One vacant building rehabbed by Habitat was inhabited this period. Unfortunately, four homes were burned this period and three families relocated. |

In terms of reducing crime and increasing the quality of life it is an imprecise formula and often not practical nor possible to describe and support a singular strategy to remedy the situation due to the transient nature of the problem, longevity of the problem or how the neighborhood perceives the issue (Hotspots, 2008). As was the situation in York where resources are scant and public expectations are high. Intelligence-led policing originated in Kent Police England in the early 1990’s with the sole purpose of reducing the large volumes of crime (Intelligence-Led Policing, 2008). Intelligence today have a host of origins and as many legal obstacles for mining and purging. The information garnered by the street officer is usually genuine but at times has its origins from many input areas (neighbors, school officers, gang intelligence, etc.) and must be analyzed removing supposition and conjecture. For purpose of this discussion intelligence as to type and origin are not as important as is what is done with the information.

Intelligence Strategy in York, Pennsylvania

York City Police Department in developing COP/POP strategies utilized intelligence or data, specifically as it relates to guns, drugs and gangs have developed two types of patrol techniques. They are: Directed Patrol and Targeted Patrol. Directed patrol is generally the storm and warns type of patrol used to address a problem or may require high visibility to quell a problem or permit the officers to gain greater insight as to the systemic issues. The latter is exactly what it sounds like, Targeting the criminal enterprise or individual or establishment that is creating the problem. This technique may consume every tool in the tool box to identify players, places and ancillary groups or gangs creating the havoc.

Posited by this study and clearly supported by Eck and Maguire (2000) through their research concluding that COMPSTAT is not a stand-alone strategy; “though there is little evidence to support the assertion that COMPSTAT caused the decline in homicides in NYC, COMPSTAT is only one manifestation of focused policing in general and directed patrolling in particular” (Cited by Weisburd et al., 2003, p.235). COMPSTAT is a goal-oriented, intelligence driven, accountability process that will work in conjunction with other strategies. As illustrated by TEAM, COMPSTAT could work in most if not all criminal justice agencies and as discussed in the preceding it provides opportunity for input from all environments involved. The result for the City of York is that from 2003 to 2010 violent crime dropped 10% and with the strategies in place and if staffing remains at least similarly equivalent, it should continue to drop as indicated in tables listed for first quarter Uniform Crime Report for 2010 in comparison with the first quarter of 2009.

As most effective solutions are multi-facet so goes the case in York, Pennsylvania; the police, albeit an important component of the strategies used is only a smaller faction of the entire policy solution sought. The remainder of this discussion is dedicated to partnership solutions in addition to housing and neighborhood restoration already provided.

Poverty/Employment & Training: A strategy for healthy environments in York, Pennsylvania

Poverty Policy Influence

Race, Class, Sexual Preference, Gender, and age have always played a role in American life. The notion that these elements have been addressed and it is time to move on demands constant challenge. Slavery was introduced into York County in the early 1700’s and by 1772 there were 448 slaves in York, this in-spite of a Pennsylvania enactment outlawing the importation of slaves from overseas. The Revolutionary War reduced the use of slaves and with the introduction of the indentured servant. In exchange for transportation to this country a person may agree through contract to indenture his/her service until the final debt is satisfied. By 1780 Pennsylvania was the second state to abolish slavery through the gradual-abolishment act; those slaves born after date of legislation were free as of their 28th birthday. The system of low wage servitude created the formation of a permanent underclass (Kalish, 2010).

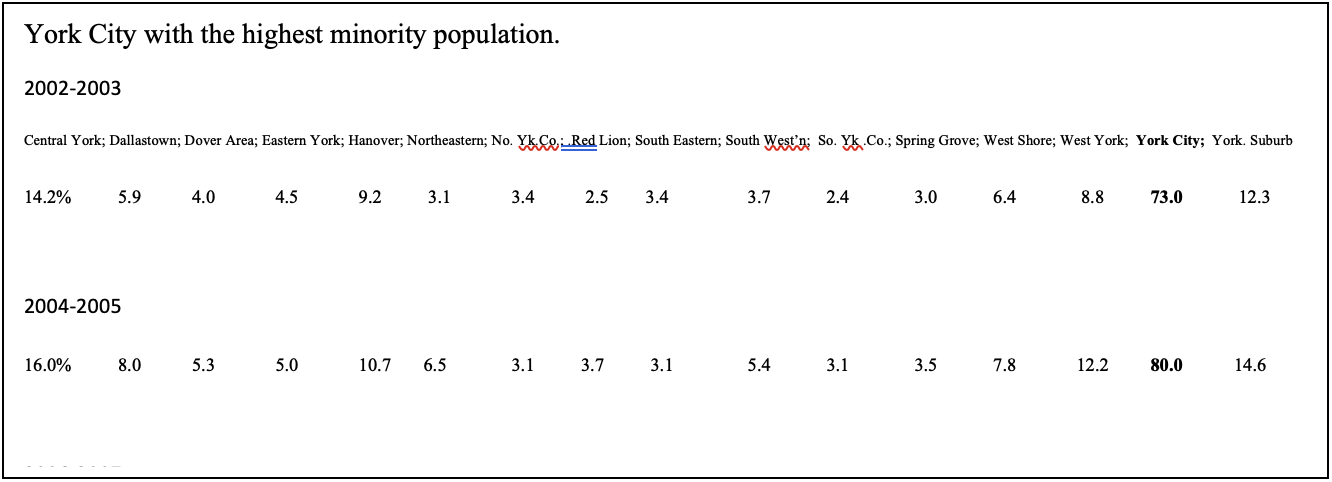

The underclass system created in 1780 remains intact at the turn of the twenty-first century. The 2000 Census Bureau Statistics exemplify the issues of York City as compared to York County and the State of Pennsylvania. In 2000, the population of the city was 40,862, and decreased in just 2 years by 610 (1.5%) while the County had an increase in population from 381,751 to 389,289 (2%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). The economic base for the city is eroding — property values in the city are dropping, while county property values are soaring. Jobs are hard to find in the City, but the County is flourishing. York County residents all enjoy the services of the hospitals and other County-wide services whose facilities are located in the City of York, but it is the poor, struggling City that has to bear the financial burden, compensating for all of the tax-exempt properties in the City that are owned by organizations who serve the wider region. Social service needs are high in the City, but revenues do not meet the needs. As conditions deteriorate, the exodus of residents and businesses shrinks the tax base even more, increasing the burden for those least able to bear it. Crime increases and there are few resources to counter the trends.

Mayor John Brenner was critical in engaging community partners with tax exempt status to help remedy a portion of the financial burden. The Mayor instituted an in lieu of tax request generally provided increases and not to mention his famous Happy Meal tax, which was a request of all County residents to pay the City of York the price of a happy meal for use of city facilities/services (The City of York is the County Seat of York County).

Other US Census 2000 statistics show that the per capita income for City of York as of 1999 was $13,439, compared to $21,086 for York County (the per capita income for Pennsylvania was $20,880.) The percentage of persons living below the poverty level was 23.8% for York City, 6.7% for the County, and statewide the percentage was 11.0%. The homeownership rate in the City in 2000 was 46.8%; York County 76.1%, and the statewide average is 71.3%. The median value for owner-occupied housing units in 2000 was only $56,500 in the City, compared to $110,500 for the County, and $97,000 for the state as a whole.

These statistics are indicative of the thriving County and point to the fact that the City of York, which not only shows values and incomes that fall far below the County’s averages, but they are also much lower than the State averages (Figure 4.0 poverty statistics).

Figure 4.0 Demographic Indicators York City vs. York County.

| Demographic Indicators | City of York # | City of York % | County Data # | County Data % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 40,862 | 381,751 | ||

| Non-white population | 40.2 | 7.2 | ||

| Home-owners’ housing costs over 35% of total income | 1,211 | 18 | 12,789 | 13.5 |

| Median Home value | $56,500 | $110,500 | ||

| Per capita income | 13,439 | 21,086 | ||

| Persons living below Poverty Level | 23.8 | 11 |

Job Training and Support Strategy

Equally important to the well-paying jobs is the interim qualifiers for family development while awaiting completion of new skills or merely making ends meet when in low paying jobs. As pointed to by Lamison and Freeland (personal communications, 2011) the Employment Skills Training Program offers life coaches for the purpose of obtaining services (safety net) for completion of job training, which is supported by a study conducted by Ryan, Kalil, & Leininger, (2009), demonstrating the need for a security blanket and support for indigent families.

Qualitative research describes how merely believing relatives or friends would help if necessary can make mothers feel less hopeless, isolated, and anxious and instill a sense of belonging (Henly, 2002; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Howard, 2006 as cited by Ryan et al., 2009, p. 280). Regardless that informal support is real or perceived, it is clear that the availability of a strong private safety net can bolster mothers’ economic and emotional well-being in the face of financial hardship. Children’s development may be negatively impacted via low income because it prevents parents from purchasing essential as well as socio critical materials, experiences or services as indicated by economic theory.

Reisig, Holtfreter & Morash (2002) contend “Generally, social theorists posit that a variety of positive outcomes is associated with healthy social networks…According to contemporary social theory, kin and non-kin social networks provide social resources that can produce a variety of desirable outcomes including employment, access to training and education, as well as instrumental, social, and emotional support” (p. 167-168).

Ryan et al. findings add to a long tradition of research illustrating the importance of social support, broadly defined, to the economic survival and emotional well-being of low-income families (e.g., Edin & Lein, 1997; Harknett, 2006; Henly, 2002; Henly et al., 2000). The research demonstrates a significant and substantively important association between the availability of a private safety net and children’s internalizing symptoms and positive behaviors. The similarity in the nature and strength of these associations across the two data sets was especially striking given the different (yet complementary) operationalizations of private safety nets in Fragile Families (which emphasized material support) and National support.

They have thus highlighted an important protective factor for children growing up in economically disadvantaged families, one that may prove especially important in the wake of welfare reform as mothers necessarily rely less on public safety nets, such as cash welfare assistance, and more on their informal networks. A note of significance is that children tend to internalize symptoms and prosocial skills strongly associated with the mother’s private safety net availability than externalizing behaviors. These results indicate that children’s behavioral adjustment may not respond strongly to changes in mothers’ safety net levels, at least not over a short period of time (relates to York City disciplinary concerns above).

Ryan, Kalil, & Leininger, (2009) find:

A positive association between private safety nets and children’s socioemotional well-being, but a different finding could have emerged. Qualitative literature on the dynamics of social support suggests that because mothers often receive informal support only on the condition of reciprocity, help from mothers sometimes can induce as much stress as it alleviates (Antonucci & Jackson, 1990; Howard, 2006) both because mothers worry about repaying their debts (financial or otherwise) and because the exchanges can complicate interpersonal relations. In these ways, mothers’ private safety nets could undermine their emotional well-being and consequently their parenting or expose children to negative relationships, either of which could disrupt children’s socioemotional development (p. 294).

More broadly, the results suggest that a group of low-income mothers exists for whom social isolation and other disadvantages overlap and that children in these families may be particularly at risk for socioemotional difficulties. As more single mothers enter the labor market under Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and it becomes increasingly critical to have a private safety net, these mothers and their children may suffer disproportionately (Ryan et al., 2009).

As pointed out by E. Lamison & B. Freeland, (personal communications, 2011) York’s Job training has taken on a new perspective, setting aside the one size fits all facade, examining the persona of an individual ensuring that the person is not set up for failure. They examine language, education, criminal history, child care issues, and then provide employment coaches to provide confidence to the person entering the workforce. This is equally effective for reintegration of prisoners who leave prison with huge debts for child support and fines. The total system is designed to deal with the concerns so the individual may be successful. The Employment Skills Training Program (ESTP) offers services for income eligible residents of York County between the ages of 18 and 54 who are currently unemployed or seeking to enhance employability.

The mission is to provide motivated individuals with outdated or unmarketable skills with information, coaching, case management and employment/training opportunities to make them viable individuals in today’s job market (E. Lamison & B. Freeland, personal communications, 2011). The significance of the coaching and case management is they aide the indigent trainee to gain the support required to make it through. This support via coaching and case management include but not limited to financial assistance, child care, gaining health care etc. (B. Freeland, personal communication, 2011).

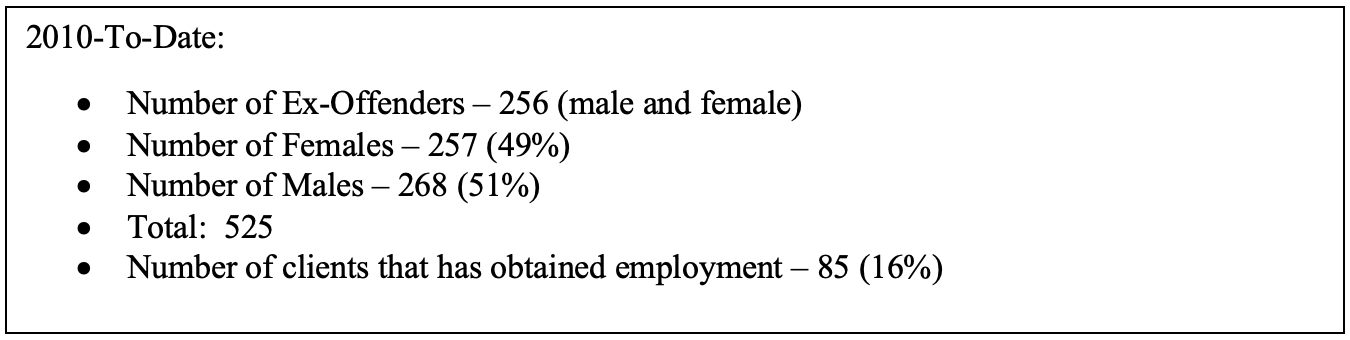

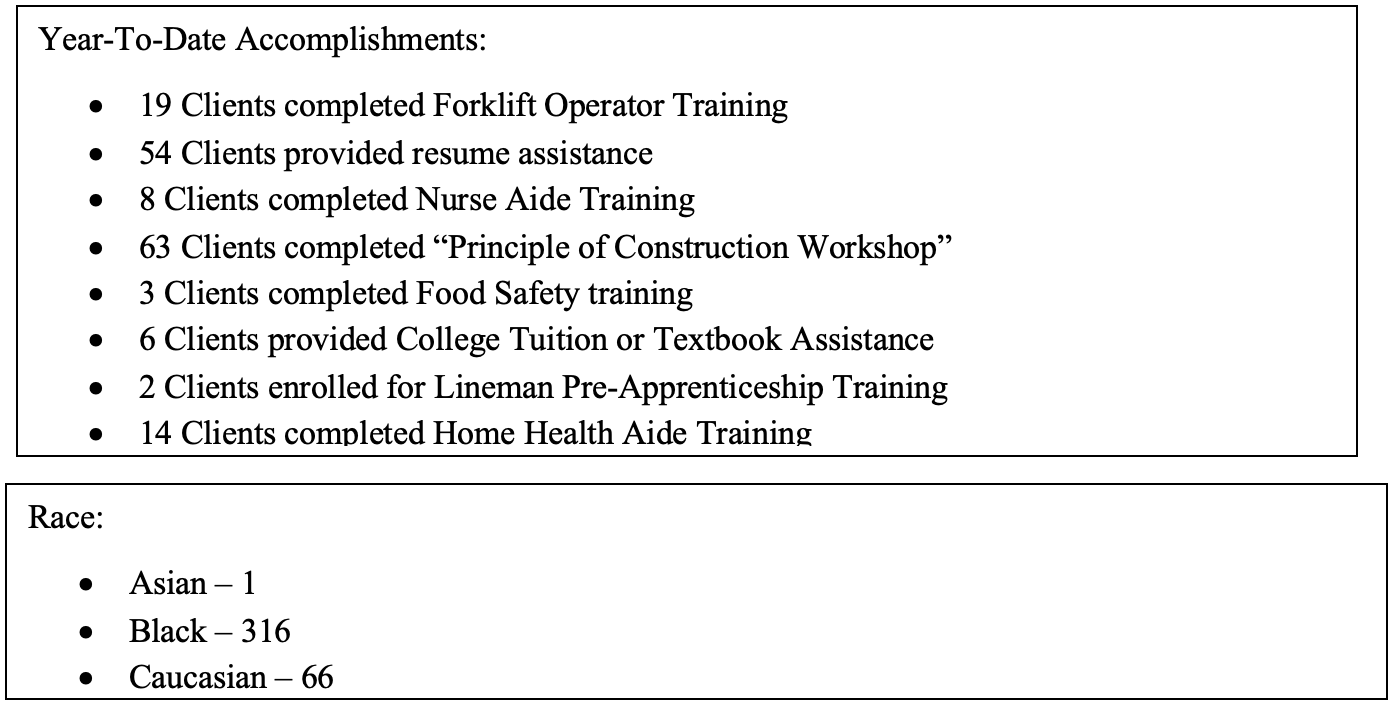

The program is in its infancy beginning in 2010, providing training needs across racial, gender, sexual or criminal history barriers with the whole persons’ ability and potential as part of the training equation. According to E. Lamison & B. Freeland (2011) the potential is recognized as not simply intelligence but if the job that the trainee is working to achieve requires a criminal history background investigation and the trainee is a convicted felon and will not qualify, another job training is selected (not a program to set a person up for failure). The ESTP consists of the following core elements: Job skill assessments designed to measure foundational and personal skills as they apply to the workplace; Job analysis, which pinpoints or estimates skill benchmarks for specific job positions that individuals must meet through testing: Job searching, resume writing, and skill training to improve individual’s viability; Participation in computer training class with instructor; and Access to Full-time Case Manager and Employment Coach. This is but one program offered as a cooperative effort to increase the resource dollar for the service group rather than multiple groups vying for the same resource; and does not recognize character flaws, race or gender as a barrier but rather a qualifier for the service (Figures 5.0-5.2 program outcomes for first year of program).

Strategy Analysis in York, Pennsylvania

Thus, in conjunction with the community oriented policing and problem oriented policing strategies proffered in previous sections of this study, success can only be realized when the blinders are permanently removed and attitudes are adjusted to meet community needs. Again, no one strategy is a stand-alone process and must meld with all entities to ensure a lasting outcome; such as the family safety nets and life-coaching in job training (Remember that children having children of previous decades are our debt to society in this decade).

Education

An indicator frequently observed in city-suburban flight surveys is the absence of quality education and York is no stranger to this phenomenon (Simpson, Brenner, DeBord & Conover, personal conversation, 2011). The voluntary segregation of York schools leaves York precariously situated for civil unrest to return and may need for court sanctioned bussing as was observed in the 60’s unless other solutions are initiated (consolidation of school districts, charter schools or private education). The voluntary segregation differs from the forced segregation in that this is due to the flight from inner cities of the economically advantaged leaving the economically disadvantaged with no or little ability to pay for required resources.

Currently the City of York has six charter schools which are: Crispus Attucks Charter School; New Hope Academy; Lincoln Edison; Helen Thackston; International Baccalaureate Charter School; and the Logos Academy and one parochial elementary and one parochial high school. The funding mechanism for each will vary from public dollar supported to public dollar/private contribution support. According to Bobby Simpson (personal conversation, 2011), charter schools are independently run, good teachers, school board that participates and is supportive, accountable to parents and requires parents accountable to teachers and maintains the discipline of a private institution and Catholic Schools and students are more academically challenged and placed for future academic ventures, however they have yet to improve standard test scores as has Catholic or private institutions.

Numerous studies have been conducted to support Mr. Simpson’s assumptions. Carbonaro’s & Covay’s (2010) contend “findings were consistent with prior research. First, Catholic school students experienced larger math gains from 10th through 12th grade than comparable public-school students. This finding is consistent with research from both High School and Beyond (HS&B) data set, a longitudinal sample of 10th- and 12th-grade students in 1980 and 1982.(HS&B) and National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988(NELS:88) (Bryk et al.1993; Gamoran 1996; Hoffer 1998; Hoffer et al.1985 cited by Carbonaro & Covay, 2010). Thus, changes in the Catholic and public sectors have not eliminated the Catholic advantage in high school achievement; it is now observable over a 20-year period beginning in the 1980s through the early 2000s. Sector differences in Educational Longitudinal Studies (ELS) are substantially smaller than those found in analyses of HS&B” (p.176). Regardless, a decade of standards-based reform has not eliminated the gap in achievement growth among public and private high schools.

Second, despite standards-based reforms in the public sector during the 1990s, private school students were still taking more advanced math courses than their public-school counterparts. Perhaps more importantly, public school students were still less likely than private-secular and Catholic school students to enroll in advanced math courses even after controlling for family background characteristics and prior achievement. Thus, it appears that otherwise similar students are exposed to substantially different learning opportunities in public and private schools. Carbonaro & Covay (2010) maintains that “Sector differences in course taking were substantively meaningful: Our findings show that private school students were more likely to go much further in the math curriculum than their public-school counterparts” (p. 177). This is especially important given that math course taking in high school is an important predictor of college enrollment and completion (Adelman 1999 cited by Carbonaro & Covay, 2010). Although important it is difficult to find gains in York’s math and reading in the standardized testing without advancing students to advanced math, as indicated by York City School Statistics.

Finally, consistent with prior research of school sectors, most of the Catholic and private-secular school advantage in achievement was explained by differences in course taking among students. This finding is largely consistent with other studies that suggest that private school students benefit from exposure to a more rigorous academic curriculum than their counterparts in public school (Bryk et al. 1993; Hoffer et al. 1985 cited by Carbonaro & Covay, 2010, p. 177). These analyses also produced some important differences with prior research on school sector and achievement. Unlike prior studies of school sector, they examined sector differences in both gain scores and specific math skills; arguing that simply focusing on gains scores provided an overly narrow view of sector differences in achievement (Carbonaro & Covay, 2010).

Carbonaro & Covay hypothesized that since standards-based reforms targeted students in the lower half of the achievement distribution, sector differences in math skills would be largest for more advanced skills. The study’s findings supported this hypothesis and produced findings sector differences in those students taking advanced course paid substantial dividends for students’ higher level math skills. This is especially important to recognize since students with weak math skills are more likely to take remedial courses when in college, which increases their risk of leaving postsecondary education (Adelman 2004 cited in Carbonaro & Covay, 2010).

However, it is important to note that very few students in public or private schools reached proficiency in the highest level of math skills. Thus, all schools, regardless of sector, need to provide additional resources to help students at the high end of the achievement distribution master the most challenging parts of the math curriculum. Although the curriculum is critical for challenging the masses, it is equally important to provide the resources for the disadvantaged educational campus. The correlation between private, Catholic and Charter Schools is important to York’s future educational success, albeit Charter Schools were not the specific subject of studies provided by Carbonaro & Covay, they mention the charter school proposition as part of the overarching differences but statistical data specific to the charter system is not as abundant. They further contend that it is not a leap of faith to lump the three systems together as they are of similar characteristics (Carbonaro & Covay, 2010).

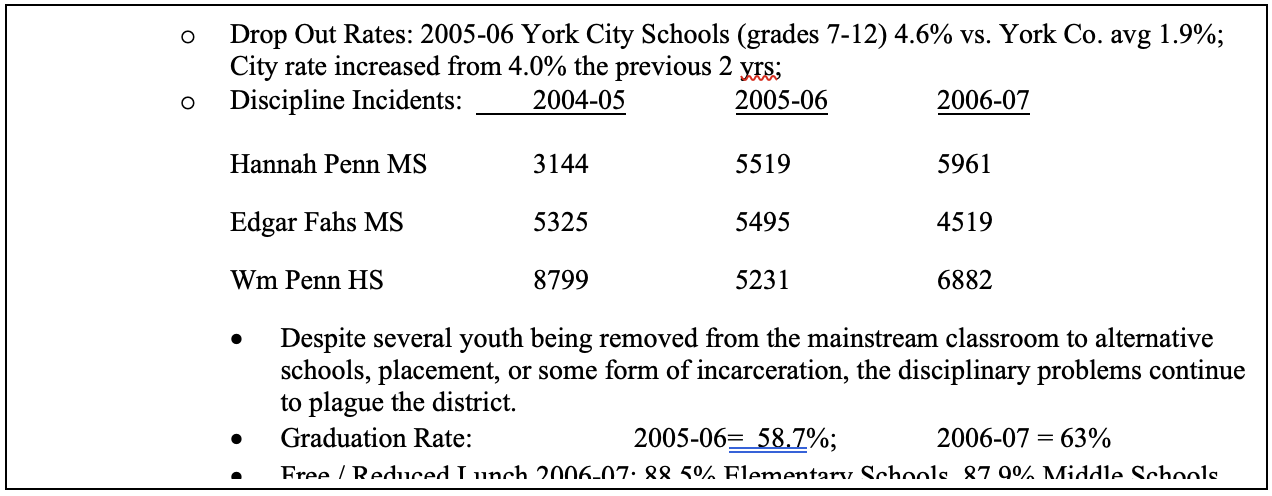

York has undergone an educational transformation in the past forty years from de-segregation in schools during the 1950’s and 1960’s to the advent of charter school systems within the York City School District According to Simpson (2011) Crispus Attucks provided the first charter school in York City (Simpson, personal conversation, 2011). York’s Educational system has been the topic of reports due to a decline in resources and educational opportunities preceding the riots of 1969 and since, for example the York Human Rights Commission held numerous hearings and analysis, the Charrette at York, (1970), post-riot healing process and York Counts, 2009 has established this as one of the top three issues to address in the region (DeBord, 2011). What does persist as a disruptive issue for providing an educational environment is the disciplinary problems and dropout rates (Kalish, 2000, Simpson, 2011, DeBord, 2011) which is indicative of poverty and disciplinary issues in York City (Figure 3.0-3.1 school system statistics).

High school dropouts are three and one-half times more likely than high school graduates to be arrested, and over eight times more likely to be in jail or prison. Across the country, 68 percent of state prison inmates do not have a high school diploma. While staying in school even one year longer reduces the likelihood that a youngster will turn to crime, graduating from high school has a dramatic impact (Lochner, & Moretti, 2004). Although York’s progress has been observed dealing with segregation issues over the past forty years the decline in quality education continues to haunt the city. This singular issue has impacted housing, flight from the city, crime and poverty (Simpson, Brenner, DeBord & Conover, personal conversation, 2011).

Evaluation of research assessing the policy’s current outcomes and unanticipated consequences / Description and evaluation of the research methods to assess the outcomes of proposed modifications

Methodology

The information contained is a historical review of the City of York along with contemporary studies to support the processes configured to date. A longitudinal qualitative study observing the forward momentum of the City of York is best suited for evaluation purposes. The tumultuous bigotry of the sixties has given way to the collaborative methods pursued under the Brenner Administration. The 1960’s data researched has provided a baseline for which many attempts have been administered until a more positive approach of the all-encompassing philosophical and strategic programs and methodology under Mayor Brenner. Brenner’s approach is community policing; education; job training; and neighborhood improvements in parks and recreation and housing as witnessed by the East Princess Street project and now the West Princess Street project as interconnected collaborations of several strategies for the purpose of increasing the quality of life to City residents. The longitudinal observation requires data collection for a ten-year period from 2003-2013 to best analyze what works, what does not work and have attitudes been modified to the extent that true cooperation is evident from all entities and not solely reliant on police for community rehabilitation.

Data Analysis

The data collection and continued observation of the west end project likened to the east end project will constitute a correlational analysis. Dependent upon the data collected may provide comparative data. The future study must understand its limitations as well, thus requiring greater scrutiny as to available resources during each project; also the length and commitment of cooperation from all participants; and the addition of any new participants. The question studied is: Will the Public Policy legacy from one administration extend into the next for embellishment or will it be terminated in favor of new administration policy that is credited solely to the new administration? In the political landscape of the past a line of demarcation between administrations and policy direction was generally tied to each administration. The study will represent a quasi-experiment as the independent variables cannot be controlled, but the outcomes certainly can be measured (East Princess Street Neighborhood restoration in comparison to West Princess Street Neighborhood restoration; crime statistics; job training and reintegration programs progress and housing to name a few). The ability to act in unison and with collaboration of strategies may demonstrate a relationship between the successes measured; albeit insufficient to demonstrate the causal linkage.

Conclusion

National studies of adults point to lower levels of trust in government among ethnic minorities when compared to the majority (Flanagan, et al., 2009). Similarly, in national studies of high school students, Latino and African American adolescents, compared to their European peers, express less trust in government and are more skeptical about the amount of attention the government pays to the average person. Attitudes towards other institutions do not fare much better (Niemi and Junn, 1998, cited by Flanagan, et al., 2009, p. 503).

Not unlike York’s history, ethnic awareness also was positively related to commitments for improving race relations and especially to the civic goal of advocating for one’s ethnic group. Notably, in contrast to the role of prejudice in family discussions of the personal barriers it poses and to the role of prejudice in undermining youth’s beliefs in the American promise, reports of prejudice were unrelated to any of the three civic commitments. The fact that ethnically aware youth were more motivated to improve race relations and to advocate for their group is consistent with research on immigrant youth which shows that civic engagement often takes the form of assistance and advocacy for one’s ethnic group (Lopez and Marcelo 2008; Stepick et al. 2008, as cited by Flanagan, et al., 2009, p. 515).

Lee (2010) contends

The ethical awareness should be included in curriculum development in schools today. The study recognizes the generational differences between herself and the children in her school. It is time that we’re really open and aware that the America of my childhood is not the America of today.” She considers that contemporary diversity is so common and natural. Today’s children are accepting, and this little Caucasian boy’s best friend is the little Vietnamese boy that’s sitting beside him. It’s natural to them (p.28).

According to Grant and Ladson-Billings (1997), the “curriculum change “approach is considered best for multicultural education, where the focus is more on transforming the curricular components including basic values, beliefs, and sociocultural assumptions. Using this “curriculum change” approach, teachers should examine their practice to consider whether their curriculum takes into account diversity by comprehending and valuing cultural pluralism and challenging or changing biases and prejudices toward other cultures (as cited by Lee, 2010, p. 26). Albeit York City has witnessed improvements if not more significant awareness within recent years Lee points to limitations of not only this review but that which is required to improve future generations in York.

In asking, ‘‘what does it mean to be an American?’’ Walzer (1990) notes that, although we have appropriated the adjective, there is no country called America. Our sense of ourselves is not captured by the fact of our union. Rather, we are bound by the commitment to tolerance codified in our Constitution. What makes us Americans is a commitment to respect others who are different from us and with whom we may ardently disagree. With each new generation we renegotiate the principles that established our nation and that define our collective identity (Flanagan, 2009, p. 516).

This evaluation has demonstrated the significant evolution realized by the City of York, primarily in the last ten years to build trust, the economy through job creation and job training, the police building bridges, but the school district remains in the greatest peril. York has improved at glacier speeds and probably as human attrition occurs changes will follow. The thrust of this discussion was to demonstrate that COP is a multi-facet attitude modification philosophy that entails each segment of the area. The POP is a management philosophy based on hard, live and real time data critical to the mission. The police although important are a small portion of the puzzle and it takes an entire community to make a difference. In York’s situation the missing component for growing a community is a successful educational system. A community such as York City that is reinventing itself must provide a healthy and vibrant educational system in order to support family life, vital to the COP/POP philosophy and is conspicuously absent from the equation to date. A journey is defined as the distance between two points: York has many miles traveled with many miles to go, with no end point defined!

References

Blumstein, A., and Wallman, J., Eck, J., E., & Maguire, E.R., (2006). Have changes in policing reduced violent crime? An assessment of the evidence. The crime drop in America (pp. 207-265, Chapter 7). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bunch, W. (September 2, 2001). “Handcuffed By History”. The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

Burns, P. F., & and Thomas, M. O. (2005). Repairing the divide: An investigation of community policing and citizen attitudes toward the police by race and ethnicity. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 3(1/2), 71-85.

Carbonaro, W., & Covay, E. (2010). School sector and student achievement in the era of standards based reforms. Sociology of Education, 83(2), 160-182. Doi: 10.1177/0038040710367934

Chan, J. (2011). Racial profiling and police subculture. Canadian Journal of Criminology & Criminal Justice, 53(1), 75-78. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=57439656&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Chappell, A. T., Maggard, S. R., & Gibson, S. A. (2010). A theoretical investigation of public attitudes toward sex education. Sociological Spectrum, 30(2), 196-219. Doi: 10.1080/02732170903496117

Choi, C., Turner, C., & Volden, C. (2002). Means, motive, and opportunity: Politics, community needs, and community oriented policing services grants. American Politics Research, 4,

Clines, F. X. (May 17, 2001). “Mayor Says He Expects to Be Charged in 1969 Killing”. The New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2008423-455.

Fagin, J. A. (2007). Criminal justice (2nd Ed.) Allyn and Bacon.

Flanagan, C., Syvertsen, A., Gill, S., Gallay, L., & Cumsille, P. (2009). Ethnic awareness, prejudice, and civic commitments in four ethnic groups of American adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 38(4), 500-518. Doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9394-z

Frey, W. H. (2011). Melting pot cities and suburbs: Racial and ethnic change in metro America in the 2000s. (Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings). Brookings 1775 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20036: Brookings. Retrieved from http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2011/0504_census_ethnicity_frey.aspx

Gabor, T. (1994). The suppression of crime statistics on race and ethnicity: The price of political Correctness. Canadian Journal of Criminology& Criminal Justice. 153-163.

Hickman, M. J. (2008). On the context of police cynicism and problem behavior. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 4(1), 1-44.

Hilliman, C., Dr. (2008). The intersections collection. U.S.: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Horn, M. F. (2008). Data-driven management systems improve safety and accountability in New York City Jails. Corrections Today, 70(5), 40-43. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=36188289&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Kalish, J. (2011). The York Crispus Attucks Story: 1931 to 1996. Unpublished manuscript.

Kalish, J. A. (2000). The story of civil rights in York, Pennsylvania. York, PA: York County Audit of Human Rights.

Lee, S. (2010). Reflect on your history an early childhood education teacher examines her biases. Multicultural Education, 17(4), 25-30. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=58487956&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Longman, J. (2001, 01 Nov 2001). A city begins to confront its racist past. The New York Times, pp. 18. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.comezyproxy.hacc.edu/docview/431926791?

Lueck, T. J. (2002, 20 Oct 2002). Former mayor is acquitted in ’69 race riot killing; two others are convicted. The New York Times, pp. 1-16. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.comezyproxy.hacc.edu/docview/432215999?

Marion, N. E., & Oliver, W. M. (2006: 2012). The public policy of crime and criminal justice (2nd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

McDonald, P., P. (January 2004). Implementing COMPSTAT: Critical points to consider. The Police Chief, 33-37.

Moore, M. H. (2003). Sizing up COMPSTAT: An important administrative innovation in

policing. Criminology & Public Policy, 2, 469-494.

New York Times. (2002, 19 Dec 2002). 2 men are sentenced for killing of woman in 1969 race riot. The New York Times, pp. 37.

New York Times. (2002, 15 Aug 2002). 4 defendants reach plea agreements in race riot killing. The New York Times, pp. 16. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.comezyproxy.hacc.edu/docview/432159593?

New York Times. (2003, 22 Apr 2003). 2 black men draw prison for ’69 killing of white officer. The New York Times, pp. 16. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.comezyproxy.hacc.edu/docview/432373265?

New York Times. (2003, 14 Mar 2003). Blacks convicted in ’69 killing of York officer. The New York Times, pp. 27. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.comezyproxy.hacc.edu/docview/432352269?

Newman, D. M. (2007). Identities and inequalities: Exploring the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Office of Justice Programs. (2004). Bureau of justice statistics-crime in the U.S. Washington, D.C.: BJA: Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved from http://bjsdata.ojp.usdoj.gov/dataonline/Search/Crime/Local/JurisbyJuris.cfm?NoVariables=Y&CFID=19152804&CFTOKEN=33396494

Ore, T. E. (2009). The social construction of difference and inequality: Race, class, gender, and sexuality. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. (1968). Audit on human rights. Harrisburg, PA: PHRC.

Reisig, M.D., Holtfreter, K., & Morash, M. (2002). Social capital among women offenders: Examining the distribution of social networks and resources. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 18 (2), 167-187.

Ryan, R. M., Kalil, A., & Leininger, L. (2009). Low-income mother’s private safety nets and children’s socioemotional well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 278-298.

Sklansky, D. A. (2006). Not your father’s police department: Making sense of the new demographics of law enforcement. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 96(3), 1209-1243. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=21820080&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Smith, B. W., Novak, K. J., & Frank, J. (2001). Community policing and the work routines of street-level officers. Criminal Justice Review, 26(17-37)

U.S. Census Bureau (2000). http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en

Statistics from the 2000 U.S. Census support the contention that the City is suffering severe hardships in a region of plenty. Comparisons of several demographic factors from the US Census 2000 clearly illustrate this:

Walsh, W., F., & Vito, G., F. (February 2004). The meaning of COMPSTAT. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 51-69.

Weisburd, D., & Eck, J. E. (2004). What can police do to reduce crime, disorder, and fear? Annals of the American Academy of Political & Social Science, 593, 42-65.

Weisburd, D., Mastrofski, S. D., McNally, A. M., Greenspan, R., & Willis, J. J. (003). Reforming to preserve: COMPSTAT and strategic problem solving in American policing. Criminology & Public Policy, 2, 421-456.

Willis, J. J.; Mastrofski, S. D.; & Weisburd, D. (2004). COMPSTAT and bureaucracy: A case study of challenges and opportunities for change. Justice Quarterly: JQ /, 21(3), 463-496.

York Counts 2009 Indicators Report. http://yorkcounts.org’