Chapter 12: Finding Ethical People from an Unethical Society

Abstract

This Chapter provides readers a look at Noble Cause Corruption and how it may facilitate itself among police officers. This section also provides reprinted portions of the author’s research on pre-employment testing of police candidates. The section illustrates that police agencies that use the processes provided herein generally have a good fit employee that is generally ethically fit for the position. Readers should identify and evaluate gaps from pre-employment testing to the systemic issues that may lead to a lapse in ethical judgement. This material albeit subscribes to criminal justice members, it may be applicable to other disciplines.

Introduction

Readers are advised that for this material to make sense to them, it is essential that they do not park their brains at the door! Simply put, bring forth knowledge obtained from previously engaged disciplines of Sociology, Psychology, Anthropology, Criminology, and History to name a few. There is no one single silver bullet that provides a simple answer to social issues. Simply put the etiology of ethics is tangential at best.

The awesome responsibility of local, state and federal governments to provide safe environments for its citizens is greater than one can imagine, but is often taken for granted and more so often generates a sense of complacency by citizens. No greater responsibility is vested in persons to carry out the function of protection and safety than on the members of the United States Military and the police officers within the near 18,000 police agencies in this country (Reaves, 2011). Generally this task is fused within statutory authority, partially due to the reasonable societies entering into the social contract theory. The social contract theory can be found in the early writings of philosophers such as Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato, into the social contract thinker era of Thomas Hobbes (1651), John Locke (1689), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762), and within the fabric of our justice system (Albanese, 2012; Pollack, 2010).

The Social Contract theory institutes a suitable affiliation between members of society and their government. Social contract argues that individuals willingly relinquish certain freedoms and unite into political societies, abiding by common rules, and accepting the corresponding duties of providing protection from one another and other types of harm. The social contract theory provides that law and political order are the creation of man and contrived for the purpose of public tranquility administered by government (Albanese, 2012; Pollack, 2010).

The United States is a country that is governed by the “Rule of Law.” Government in the U.S. gains its statutory authority through the U.S. Constitution, which further organizes and structures societies into state governments with State Constitutions, which is further subdivided into smaller units of governmental municipalities with local codes. The social contract theory, vests in police the authority to address public behaviors, laws and norms on behalf of societal members. This means that society have given up the right to address grievances against them (Pollock, 2010). Through the social contract theory the police are willingly provided their authority and power by its citizenry. At the same time, society has expected and continues to expect the highest degree of integrity, professionalism, accountability, and trustworthiness, and ethical behavior from their police during the process (Conditt, 2001; Seron, Pereira, & Kovath, 2004).

The ethical make-up of police officer candidates, which eventually become police officers, is critical to the organizational integrity of the agency (Pollack, 2010). A significant fashion by which society measures the organizational integrity is generally through the conduct of its personnel. This dimension entails misconduct, social deviance, or misrepresentation of public trust either on duty or off duty by police officers that undermines the public’s faith in its police (Palmiotto, 2001). Albanese (2012) contends,

Ethics is central to criminal justice because morality is what distinguishes right from wrong-in differentiating the government’s moral authority to enforce the law from the immorality of the crime itself…Only by being moral can criminal justice be distinguished from the very crime it condemns (p. 3).

Thus far, readers have availed them self to ethical leadership, corruption, attempting to distinguish between deviance and crime, and made mention of suitable, efficient selection of police officers to perform ethically in an unethical society. This section is intended to illustrate the police officer selection process as a key component of organizational effectiveness. Specifically emphasizing the initial selection is an important phase of developing organizational integrity. This can develop the first stage of future leadership within the police organization. The police middle manager and police leaders are responsible for establishing the ethical environment and climates of their departments. The control of police corruption is virtually impossible when police management fails to address unethical behaviors of its officers (Vito, Wolfe, Higgins, & Walsh, 2011).

Noble Cause Corruption

In most instances candidates of police departments are often motivated by the ability to make a difference. In other words to help the less fortunate, the injured, the victim, and overall to do so in a noble fashion. Caldero and Crank (2004) assert that “noble cause is a moral commitment to make the world a safer place “(p. 17). Again an admirable trait in which to enter the profession. The problem that arises from strict adherence to this cause is when the ends justifies the means rather than compliance with an oath of office. When the use of short cuts supersede due process on a routine basis, there exist a potential for corruption.

At this juncture I draw your attention back to the “Group Think” mentality previously cited in a previous chapter. When a police officer finds herself/himself cloaked in the deception of invulnerability; when cohesion of the group (fellow police officers) takes precedence over sworn obligation; and when he/she falls prey to a rationalization process over duty, often unethical behaviors surface. They surface in-spite of original noble purpose and good intentions that drew the officer to the police calling. Because officers are frequently dealing with violence and the seamy side of life, the rationalization process may favor closure for those victimized over due process for those that violate the law. At this juncture officers are more concentrated on an end result and they may resort to unethical and perhaps illegal methods to protect the victim.

A safeguard provided by Pollock (2010) he suggests when confronted with noble cause corruption the officer should consider the following questions:

- Is the activity perceived as illegal?

- Is the conduct permitted per departmental policy?

- Is the activity perceived unethical or is the activity actually unethical?

- Is the activity acceptable under any ethical system, or just utilitarianism?

Succinctly, if it feels unethical or illegal, than it probably is. Agency members should be cognizant that “just because you can, does not necessarily mean you should” conduct oneself in a particular fashion. Judges, Lawyers, and juries often have months upon years to examine officer behavior that is right, but perhaps find that it may not have been the correct action to take.

Josephson (1998) posits “Character may determine our fate, but character is not determined by fate” (p. 2). An alternative view offered by Punch (2009) moves away from the individualist characteristics of ethical lapses to a broader base of managerial shortcomings and systemic organizational failures. In his book, Police corruption: deviance, accountability and reform in policing, he provides case studies of police departments throughout the world. He briefly concludes, resulting from his examination of each agency, that in each of these events always highlight aspects systemic failure and perhaps larger governmental oversight missteps.

Purpose of Candidate Testing

Police officers are not ordained nor are they introduced to a heredity purification process which uniquely qualifies them for the tasks ahead in their careers. So then how can state and local agencies ensure they will be getting the best fit candidates to fill police positions? One topic of note is the ethical foundation the entry level police officer brings into the profession after preemployment scrutiny ought to equate to the organizational integrity as a result of eliminating the candidate that is not suitable for police work. According to Albanese (2012) and Pollock (2010), character is the building block of ethics and all ethics are learned behaviors.

The following content is from the author’s research that provides a best practice for prescreening of police officer candidates. Thus, attempting to demonstrate a significant relationship between the types of police candidate preemployment testing and the negative impact of such testing on disciplinary and termination actions due to ethical violations. Investigating the correlation between preemployment screening and predicting unethical behavior in police candidates is the main focus of the authors study. Volumes of existing literature indicate ethics is critical in policing but there is limited research to describe how ethical candidates are identified (Gardner, 1990; Ivkovic`, 2003 & 2005; Kotter, 2001; Kanungo, 2001; Kane, 2002; Kouzes & Posner, 2007; Kane & White, 2009; Wolfe & Piquero, 2011).

Previous studies have established that in many instances preemployment screening of police officer candidates occurs through such procedures such as background checks, truthfulness testing, and psychological testing that is related to uncovering pathological or criminal behavioral predictors of the candidates (Arrigo & Claussen, 2003; Banish & Ruiz, 2003). The literature is scant which examines the usefulness of the preemployment screening processes of police officer candidates in areas such as written examinations, background investigations, truthfulness testing, medical examination, and psychological testing in predicting likelihood of disciplinary or termination actions for ethical violations. Likewise, the existence of a best practice for preemployment screening of police officer candidates is absent in the literature. In essence what works and what does not work is not yet known. It is therefore important to investigate the prescreening process of officers hired over a ten-year period of prescreening candidates in comparison to the actual number of ethical violations resulting in a disciplinary hearing and/or termination.

Whitman (2013) maintains his work may be important to the policing industry as it may provide an effective correlational measurement of ethical profiling of candidates reducing liability for the police organization and leadership as well as reducing loss of costly and highly trained members of the police organization due to ethical violations. Police officer selection is paramount for the organizational and the community effectiveness, integrity, and legitimacy. The selection process is the first phase of developing organizational integrity and is likely the initial building block for developing future leaders within the police organization. Also vital to the integrity of each police agency is not only the proper hiring of personnel, but the retention, training and discipline of its members in order to maintain qualified members who will act ethically and responsibly (Vito, et al., 2011). This is further chief to ensure an adequate defense in the case of law suits against agencies. Whitman’s study is an investigation of existing practices of police agencies during the hiring phase (prescreening) and its negative impact on ethical violations of the police officer after hire. This quantitative investigative study was designed to research the correlation between the preemployment screening processes and examine which processes result in the least disciplinary actions.

These works of collective scholars provide the backdrop for this research in that deviant, criminal, and violent behavior predictors may require mining from multiple sources of the police officer candidates social setting, mental health, personality, and genetics in order to gain the most fit candidate for the police officer position. The outcome of ethical behavior is learned over a police officer candidate’s life-time and thus the theoretical framework selected as the best fit for this study is Akers Social Learning Theory.

The Study

Study Population

The population selected for this study is the law enforcement executives of a notable police chief’s organization (NPCO) charged with the responsibility of hiring police officers. Purposive sampling was the best fit for this study because people or other units are selected due to a specific purpose they fulfill. The participants’ involvement in the study was completely voluntary.

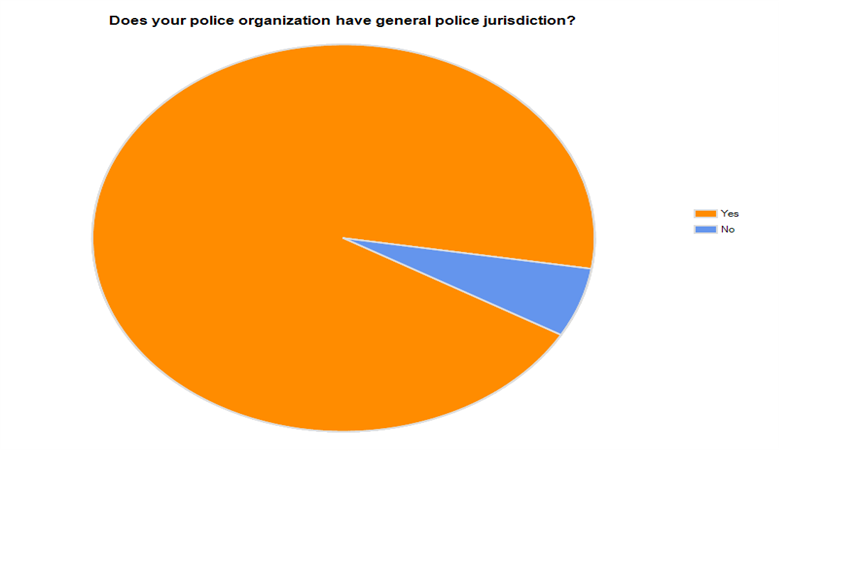

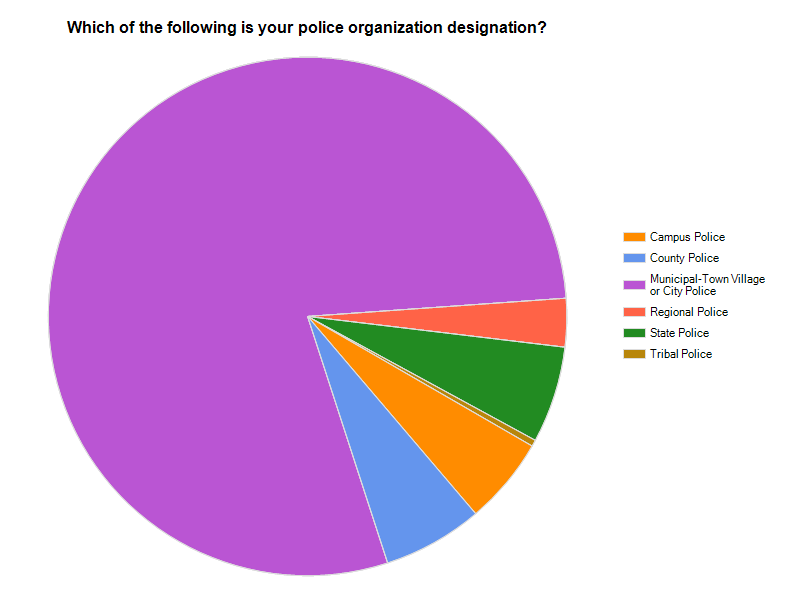

The cross-sectional study was limited to law enforcement executives (Police Chief, Police Commissioner, Director or Superintendent) of police organizations within the United States (excluding federal and international members) with general law enforcement jurisdiction. Although not longitudinal, data reports from participants spanned a ten year period. The participating agencies voluntarily submitted data in the questionnaire that identified the organization by state agency (state police organization with statewide jurisdiction), municipal agency (towns, village, city or tribal police are defined within this category), regional agency (county police are defined in this category), or campus police (full police authority limited to campus jurisdiction) as well as the number of sworn members.

Data Collection

This study is a non-experimental and cross-sectional correlational study. The self-administered survey/questionnaire was electronically administered by Survey Monkey to the identified police agencies. The participants were solicited from the membership list of a leading police leadership organization in the United States with an anticipated return of 250 participants from the potential of 5,049 members that meet the definition of Agency Head for this research. Bordens & Abbott (2011) contend “there is significant advantage to using the internet to conduct a survey or recruit participants: You can reach a large body of potential participants with relative ease…Data can be collected quickly and easily, resulting in a large data set” (p.270). The police agencies returning completed surveys ranged in size (sworn police officer strength) from small (less than 50 members), medium (51-500 members), and large agencies (500 and up members) representing differing geographic regions across the United States. All agency participant information was submitted without an identifier of any type.

The research letters requesting participation made it abundantly clear that no participant identification would be included in the survey/questionnaire and data would be analyzed in aggregate format. The survey design selected provided a quantitative or numeric description of trends, and the population from a sample of that population. The data collection method was selected in order to generate data about the preemployment testing procedures and the number of ethical violations recorded and processed since the inception of the current preemployment screening process used by the responding participant.

This research explored the relationship between police officer candidates’ ethical orientation by identifying predictors during the preemployment testing process and the number of ethical violations resulting in a hearing or termination of the police officer having been subjected to the preemployment testing. The research design employed a correlational statistical analysis technique to examine the influence of variables. The methodology and design in this study is similar to that put forth by Creswell (2009) which investigated a dominant variable that is influenced by multiple independent variables.

The purposeful sample for this study was pulled from the membership of a NPCO. All active members meeting the definition of Agency Head were solicited to participate. The expected return rate was 250 participants providing an adequate sample size for measuring the correlation between preemployment screenings of police officer candidates and the number of disciplinary and terminations as the result of ethical violations. The actual return rate of the survey was N=609 and after examination of each submission for completeness of information N=545. The original return of 609 surveys represents a return rate of 12% of the potential 5,049 eligible participants. The returned survey was scored by SPSS version 20. Each of the N=545 participant surveys yielded a quantifiable numeric score representing the number and type of preemployment screening methodologies performed as well as a numeric score assigned for ethical violations during the specified research period.

Based upon demographics, preemployment screening methodologies of the participants was further divided for additional comparison among groups with multiple preemployment screening methodologies (zero preemployment tests, one-three preemployment tests performed, four preemployment tests performed, and five or more preemployment tests performed). A second separate numeric code was established indicating the number of disciplinary actions and the number of terminations as a result of disciplinary action due to unethical behavior. A data subset was established reflecting the region of the United States participants represented and using the FBI Uniform Crime Report data the population of the number of police officers impacted was identified and evaluated in aggregate format.

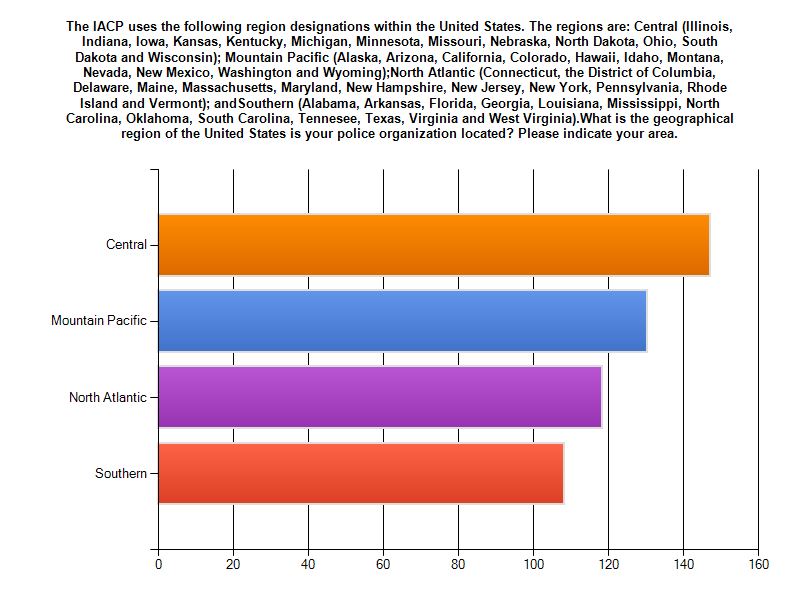

The regions of the United States are those assigned by the NPCO within the State Association of Chiefs of Police Division: North Atlantic; Southern; Central; and Mountain Pacific Regions each consisting of 12 or 13 states and the District of Columbia (IACP, 2012).

Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed using the Statistic Package for Social Science (SPSS) with prearranged separation of the data. Agencies were categorized by number of sworn members, the number of preemployment testing measures, and the number of disciplinary and termination actions that have resulted in the ten year period using their preemployment process. A predetermined numeric score was assigned to each preemployment testing procedure used by each agency. The number was then used for comparison against the number of ethical violations and terminations reported by the participant.

The hypothesis that the preemployment testing using the selection process (psychological, background investigations, written entrance exam, truthfulness and medical testing) will reduce the number of ethics violations and terminations of hired police officers was tested by comparing the number of ethical violations and terminations in the group of agencies that use no preemployment tests to those that use all five preemployment tests. A correlational research technique was used to examine a relationship between two or more variables investigating the surface relationship.

The testing technique employed was not to probe for causal reasoning, but correlation only. Both parametric and non-parametric statistics were calculated to identify statistically significant differences between the two groups. Parametric statistics are based on certain assumptions about the nature of the population and that the population is evenly distributed. This is not the assumption of the non-parametric statistic which may be better suited to identify direction and used with ordinal data or when the data is severely skewed. The specific analysis technique engaged in this study is explained in greater length in Chapter 4 of the original study, but not relevant for this discussion. Additionally, descriptive demographic information is used to establish comparability of the two groups to eliminate the possibility of contaminating variables such as geographic location or size of the agency.

The hypothesis asserts that an increase in the number of prescreening tests will be associated with a decrease in the number of ethical violations and terminations of post-hire police officers. The first and second research questions address whether the type and number of prescreening test is differently associated with number of ethical violations resulting in disciplinary action or termination. The third research question addresses best practices of preemployment screening of police officer candidates. A correlational analysis was the primary statistical test used to determine the relationship between the types of prescreening tests (psychological, medical, background investigation, psychological or entrance exam) and the number of ethical hearings and terminations. In the event an inverse direction was determined in the initial analysis, a regression technique would have been applied to determine strength of the relationship.

Additionally, this research provides a rich data set of descriptive statistics describing the components of the police background investigations and the personality and behavior components of the psychological testing used. Demographics of the police organizations collected include allocated sworn strength, geographical region of the USA, and, police organization designation.

The researcher solicited an independent analyst to enter the data from the study using SPSS in order to preclude inferences of data manipulation on the part of the researcher. Survey Monkey provided the descriptive analysis of testing mechanisms and demographics.

Instrument

Participants were sent a self-reporting questionnaire online administered through SurveyMonkey. The instrument targets the identified sample group. The survey questions attempts answers for the research questions using proper analysis and due to the uniqueness of this study the validity of the instrument will not be known until the instrument is used in other research; all research is knowledge (Personal Communication, Andrew Ryan, PhD, March 2, 2012; Susan Gray, PhD, February16, & 27, 2012). The survey instrument is researcher developed for this study and was reviewed by participating experts within the police field, establishing face validity of the instrument.

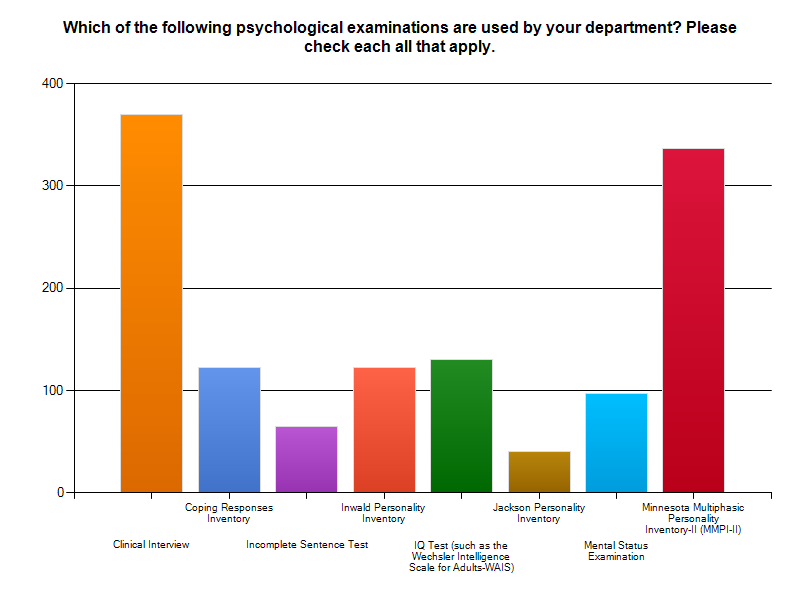

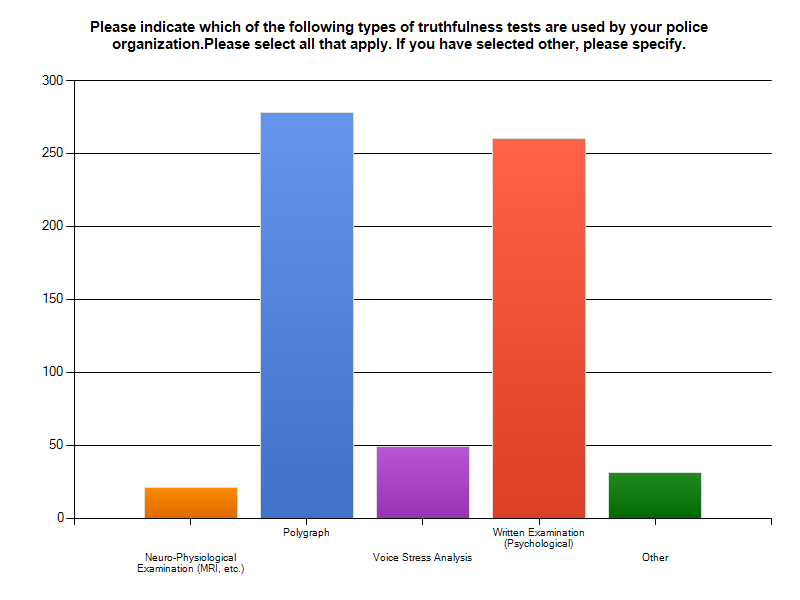

Variables included types of preemployment tests used for psychological evaluation and duration (predicting individual make-up and if he/she is a fit for law enforcement); types of truth verification tests and duration (polygraph, voice stress analysis, or other examination); types and duration of background investigations (seeking critical competent information divulging social evolution of the candidate); medical and physical agility skills testing (determine capability to perform the essential job functions); and criteria and timing of a decision to conduct a psychological examination provided (after conditional offer of employment or as part of the background investigation). The following charts are of the type of testing provided to candidates and type of agency.

The data collected was used to test the hypotheses stated predicting the correlational relationships of independent variables impact and the dependent variables. The results of the study are intended to provide a best practice model based on empirical evidence establishing a significant relationship between preemployment testing and ethical behavior of police officers. Subjected to correlational analysis data were insufficient to reject the null hypothesis or to support the alternative hypothesis and therefore further testing was unwarranted at this juncture as illustrated in the limitation section.

The validity of the questionnaire is determined from three forms of validity: content validity, criterion-related validity, and construct validity. In a questionnaire, content validity assesses whether the questions cover the range of behaviors normally considered to be part of the area being assessed; construct validity may be recognized by demonstrating that the results of the questionnaire agree with predictions; and criterion-related validity of the questionnaire involves correlating the questionnaire’s results with those from another recognized measure (Creswell, 2009; Leedy &Ormrod, 2010; and Bordens & Abbott, 2011).

Essential to systematic research is the control of internal and external validity. Internal validity refers to those portions of the study that may interfere with the cause-effect among the independent and dependent variable (Glicken, 2003). Other concerns impacting the internal validity, test-wiseness or knowing how to take a test of police officer candidates could be alleviated through the multiple testing processes of police candidates. There could be other influences which could impact the testing results of the police officer candidate during an actual preemployment testing process. This is not a significant methodological concern for this dissertation because the questionnaire is completed by the proper sample group (Police Chiefs) acting as informants on the types of testing performed in their agency and the number of ethical violations resulting in discipline or termination. Each item on the survey is clearly worded removing ambiguity in defining ethics or a violation resulting from abridging ethics. To increase confidence in construct validity the questionnaire was field tested by experts within a NPCO research committee. Comments were received and the questionnaire was amended prior to distribution of the actual survey being conducted.

Feasibility

The problems anticipated in survey completion by the law enforcement executive requiring additional research for certain existing documents including the possibility of needing to request additional information from the Human Resources component of the agency was apparently not an issue as demonstrated by the response rate. In the case of psychological testing, the executive may have needed to obtain additional information from the psychologist that administered the evaluation; however this too did not appear to hamper participant completion of the survey instrument. The anticipated survey completion was 250 agencies, but again due to the interest in this study the size of the sample did not suffer a reduction but rather a significantly greater response of actual N=609.

As part of the ongoing professional efforts, this study supports the efforts of law enforcement executives to provide public security through processes to obtain the most credible personnel. The benefits as already provided should be obvious to the participants of the study; however the greatest benefactor will be the research community. The limitations expressed will provide avenues for future research. The final study analysis will be shared with the participants and the NPCO for benefit of all law enforcement

The results of this investigation cannot statistically reject the proposed null hypothesis and is unable to support the alternative hypothesis. It does provide meaningful quantitative data that adds to the existing body of knowledge relative to police unethical behavior. The present study demonstrates that increased preemployment screening of police officers by means of the measures discussed in this study will have an increase on the number of unethical hearings and terminations rather than a negative impact as originally hypothesized. In other words greater preemployment testing of police officer candidates will result in a greater number of ethical hearings and terminations. This information gleaned from the study and the works of Sklansky (2006) demonstrates that today’s members of police agencies are less likely to look the other way. They will report the incidents of substantial magnitude but may remain silent on minor matters. Inferences from this study are statistically agreeable in a bond between the individual, the police structure, while exhibiting a departure of old police subcultures, and an allegiance to noble cause corruption summarized in the discussion.

The outcome of this research stresses the importance of the scholarly works cited in the original study. Of significance is data that indicates a shrinking of the “Blue Wall of Silence” or the interaction of organizational influences and individual factors that may result in lapses of ethical judgment. Police officers who feel the system in which they are employed is just and fair will report ethical violations.

Explicitly stated throughout the first three chapters of the original research is that no single cause for unethical behavior exists. A covenant between the individual, the organization structure and the police subculture establishes conditions in which police misconduct can occur. The sociological vetting methodologies of police organizations were measured as the focus of the study, although the police subcultures and organizational structure cannot be discounted. Conclusions of this study illustrate the need for police organizations to continually introduce ethical police officers into the membership in order to further erode the long standing police culture and misconduct that has been condoned through “Noble Cause Corruption”.

Results detailed in this research are plausible, particularly as concluded by Sklansky (2006) that the police departments of the 1950s and 1960s are not reflective of today’s police departments. In Sklansky’ s research the integration of personnel through diversification is tantamount to change in police departments, further diminishing the “Blue Wall of Silence”. Sklansky provides three main categories of hiring within police departments that are primarily responsible for the breakdown of this wall of silence. They are race, gender and sexual preference. He is further resolved that the monolithic police subculture is slowly disappearing due in part to social fragmentation of police membership through court sanctioned diversification and the generational differences removing personnel from the old cry “it’s all about the job” (Sklansky, 2006). His research attributes departmental changes to the competency of new members, the effects the community and police share as a result of diversification and the altering of organization internal dynamics. The social fragmentations within the rank and file membership of police departments today is a departure from the past primarily due to diverse membership being sought by police professional and fraternal organizations formed based on gender, ethnicity, or sexual preference (Sklansky, 2006).

These factors has aided the decline of insularity of the membership where homage and loyalty was once limited to a police bargaining unit such as the Fraternal Order of Police or The Police Benevolent Association. Police officers today maintain interests outside of police work rather than the memberships being solely about “the Job” (Sklansky, 2006; Salahuddin, 2010). Today’s police officer has a life after shift work and they will judge the fairness level of the agency of which they are a member to determine what and how much misconduct will get reported.

A study by Wolfe & Piquero (2011) of the Philadelphia Police Department provides an explanation of police misconduct, more specifically the organizational justice system as it is perceived by police. This examination of the Philadelphia Police Department depicts how personnel view the organization in structure and fairness of disciplinary application. The study included a random survey of 483 police officers employed by the Philadelphia Police Department. The results show that police officers who view their department as fair and just in its managerial practices are less likely to involve themselves in police corruption or hold fast to the code of silence or unethical behaviors such as noble cause corruption. If fair and equitable managerial procedures are practiced consistently, the more likely misconduct will result in an officer’s willingness to report (Wolfe & Piquero, 2011).

Chappell and Piquero (2004) claim that a deviant peer association is an important factor in predicting police misconduct. These authors suggest that officers, who associate with peers demonstrating deviant behavior, are themselves more likely to subscribe to the code of silence. These points are critical within the framework and conclusions of this study. Police leadership must import into the rank and file only the most ethical police officer in order to prevent contamination of peers.

Adams, Tashchian and Shore (2001) argue that structural influences can predict individual ethical behavior and moral decisions made in organizations. They also maintain that unethical and deviant behavior may be the result of situational factors that are as equally important as individual characteristics. Still, it remains their contention that ethical lapses in behavior are better explained as a merger of individual and organizational makeup rather than as independent elements (Adams et al., 2001). The concept that police corruption may be the result of social structure and police department malady is not a new proposition (Sechrest and Burns, 1992). These scholars suggest that ethical persons may have an ethical lapse of judgment as a result of life situations.

This more complex explanation is further supported by Gottschalk (2011). His work puts forward police management’s responsibility to examine both the rotten-apple (individual) and the rotten-barrel (systemic issue) because police misconduct has consequences for both. Therefore controlling the misconduct within a police organization requires examination of the individual and systemic concerns because corrupt cops are made, not born (Gottschalk, 2011). Police leadership must be able to simultaneously direct and lead across multiple generations; generations with differing values and having differing outlooks on what is right (Salahuddin, 2010). These scholars provide an avenue to better understand today’s police department member. Collectively they suggest through a general agreement for concerted attention to establishing an ethical environment for attracting the ethical individual, adhering to ethical organizational practices, and the elimination of unethical police subculture.

Research conducted by Whitman (2013) adds to the existing body of knowledge supporting the importance of examining both the individual and the system, which are not mutually exclusive. His work exercises the opportunity to combine methods to provide a more ethical candidate rather than merely justifying misconduct a single bad apple or a bad barrel approach for assigning culpability for unethical conduct.

References

Adams, J. S., Tashchian, A., & Shore, T. H. (2001, February). Codes of ethics as signals

for ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 199-211.

Albanese, J.A. (2012). Professional ethics in criminal justice: Being ethical when no one is looking (3rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Arrigo, B. A., & Claussen, N. (2003). Police corruption and psychological testing: A strategy for preemployment screening. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 47(3), 272-290.

Retrieved from http://ijo.sagepub.com/content/47/3/272

Bannish, H. & Ruiz, J. (2003). The antisocial police personality: A view from the inside. International Journal of Public Administration, 26, (7), 831–881.

Chappell, A. T., & Piquero, A. R. (2004).Applying social learning theory to police misconduct. Deviant Behavior, 25, 89-108. Doi: 10.1080/01639620490251642.

Conditt, J. H., Jr. (2001). Institutional Integrity. FBI Bulletin, 70 (11), 18-22.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gardner, J. W. (1990). John W. Gardner on leadership. New York: The Free Press.

Glicken, M. D. (2003). Social research: A simple guide. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gottschalk, P. (2011). Management challenges in law enforcement: The case of police misconduct and crime. International Journal of Law and Management, 53 (3), p. 169-181. Doi 10.1108/17542431111133409

Ivkovic, S. K. (2003). To serve and collect: Measuring police corruption. The Journal of

Criminal Law and Criminology, 93(2-3), 593-649.

Ivkovic`, S. K. (2005). Fallen blue knights: Controlling police corruption. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ivkovic`, S. K. (2009). Rotten apples, rotten branches, and rotten orchards. Criminology and Public Policy, 8, 777-785.

Josephson, M.S. (1998). The power of character. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kane, R. J. (2002). The social ecology of police misconduct. Criminology, 40, 876-896.

Kane, R. J., & White, M. D. (2009). Bad cops: A study of career-ending misconduct among New York City police officers. Criminology and Public Policy, 8, 735-767.

Kanungo, R., N. (2001). Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(4), 257-265.

Kotter, J. P. (2007). Leading change. Harvard Business Review, 85(1), 96-103.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. (2007). The leadership challenges (4th Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Josey-Boss.

Leedy, P. D., & Ormrod, J. E. (2010). Practical Research: Planning and Design (9th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Palmiotto, M. A. (2001). Can police recruiting control police misconduct. In M. A. Palmiotto (Ed.), Police misconduct: A reader for the 21st century (344-354). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Punch, M. (2009). Police corruption: deviance, accountability and reform in policing.

Collumpton, Willan Publishing, 281 pp., ISBN 978-1-8439-2410-4

Pollock, J.M. (2010). Ethical dilemmas and decisions in criminal justice. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Reaves, B.A. (2012). Hiring and retention of state and local law enforcement officers, 2008 (NCJ 238251). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=4333

Salahuddin, M.M. (2010). Generational differences impact on leadership style and organizational success. Journal of Diversity Management, 5(2), 1-6.

Sechrest, D. K., & Burns, P. (1992). Police corruption: The Miami Case. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 19 (3), 294-313.

Sklansky, D. A. (2006). Not your father’s police department: Making sense of the new demographics of law enforcement. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 96(3), 1209-1243. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=21820080&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Vito, G. F., Wolfe, S., Higgins, H.E., & Walsh, W.F. (2011). Police integrity: Rankings of scenarios on the Klockars Scale by ”Management Cops”. Criminal Justice Review, 36 (152). DOI: 10.1177/0734016810384502

Westmarland, L. (2005). Police ethics and integrity: Breaking the blue code of silence. Policing and Society, 15(2), 145-165.

Whitman, M. (2013). Investigating the correlation between preemployment screening and predicting unethical behavior in police. Capella University Dissertation.

Wolfe, S. E. & Piquero, A. R. (2011). Organizational justice and police misconduct. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38, 332-350.