2 Theories of Social Justice

Cailyn F. Green; Kim Brayton; and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will distinguish between philosophers who shaped social justice theories.

- The reader will evaluate how historical social justice theories have developed through history.

This chapter introduces students to social justice theories, covering classical, modern, and postmodern perspectives. Classical theories are distinct in focusing on the questions “What is there?” or “What sort of things exist?” (Tillman, 2021). Modern theories focus on the question of “How do we know?” Most of these were developed during the Renaissance era and are based on how we use our senses to understand things or concepts around us. Postmodern theories are based on the question “What should we do about it?”, which is a much more practical approach (Tillman, 2021). Social justice theories provide unique motives for why individuals act the way they do with respect to social justice. While many of these theories are rooted in similar concepts, they vary in explaining how individuals react and work together or against each other. Through time, social justice theory has continued to evolve, and the linear progression of this chapter allows the theories to build upon each other.

Classical Theories

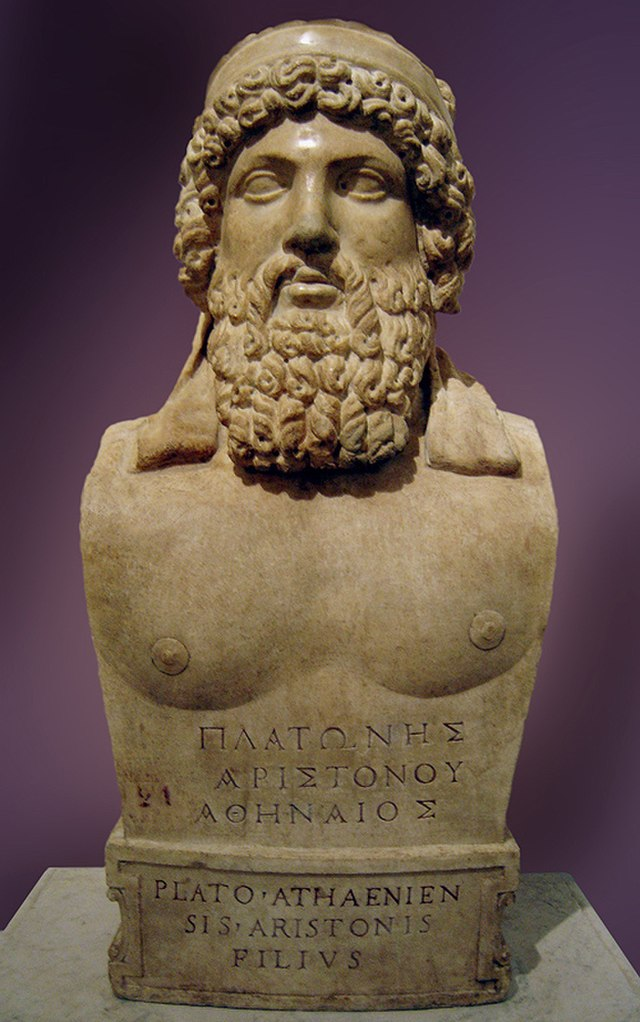

Plato’s (427-347 BC) theory of social justice was one of the first on record. Plato speaks to both mythical and religious concepts of social justice (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007) and argues that social justice is a necessary component of happiness (Kamtekar, 2001). Plato believed that the mythical gods Zeus and Apollo were held responsible for making the local rules that people lived by. Plato also believed that people themselves are not able to determine social justice equity and that a larger governing body is required to teach people what is right and wrong. Some of Plato’s drawings have been interpreted to express that fairness is embedded in every person’s character. These foundational beliefs are then expressed through a person’s behavior and actions (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007).

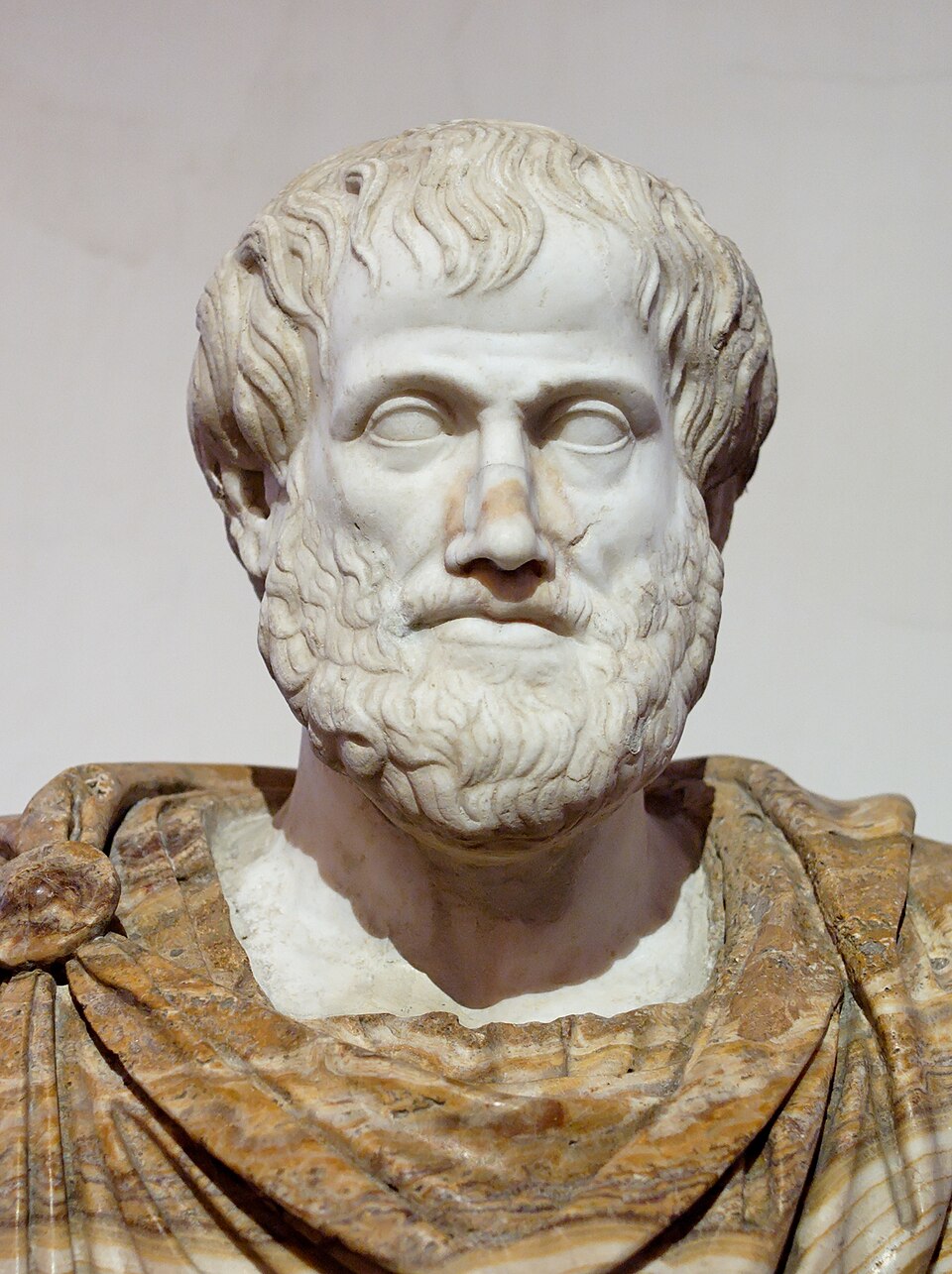

Aristotle’s (384-322 BC) theory of social justice emulates Plato, as Plato was his professor and teacher. However, there are some differences. These differences may be rooted in Aristotle’s middle-class background, which differed from Plato’s upper-class, aristocratic upbringing. While Aristotle spoke of the concept of equity being necessary for justice, he did not argue for absolute equality; he focused on proportionate equality (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Proportionate equality is the idea that equals must be treated equally and unequals must be treated unequally. An example that Aristotle gives to explain this concept is the idea of monetary exchange. If there is a shoemaker and a house builder, how many shoes would the shoemaker have to make to pay for the house builder to build them a house? These are not equal. However, all shoes can be compared as equals. So, we can identify how many shoes in general, can equal a house. Equal must be equal, for example, shoes to shoes. Unequal must be unequal, for example, shoes to house (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007).

- Why is the concept of equality important when thinking about social justice?

- Do you think that these ancient philosophers were really talking about social justice in their philosophies? Why or why not?

St. Thomas Aquinas’ (384-322 BC) theory of social justice is grounded in the concept that justice is a natural law. This is then cut into two sections. The first is general justice, which is roughly the concept of legal justice and the rules and laws the state or governing entities create for people to live by. The second section is particular justice, which explains how people distribute goods and relate to one another (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Aquinas believed that a law that is unjust or not equal is not a law. Aquinas also spoke about the distribution of goods and believed that society must monitor how goods are divided. He recognized that a person’s rank in the community impacts the goods that are distributed to them (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). St. Thomas Aquinas also considered consequences for civil disobedience to be just and necessary to maintain social justice (Scholz, 2006).

Modern Theories

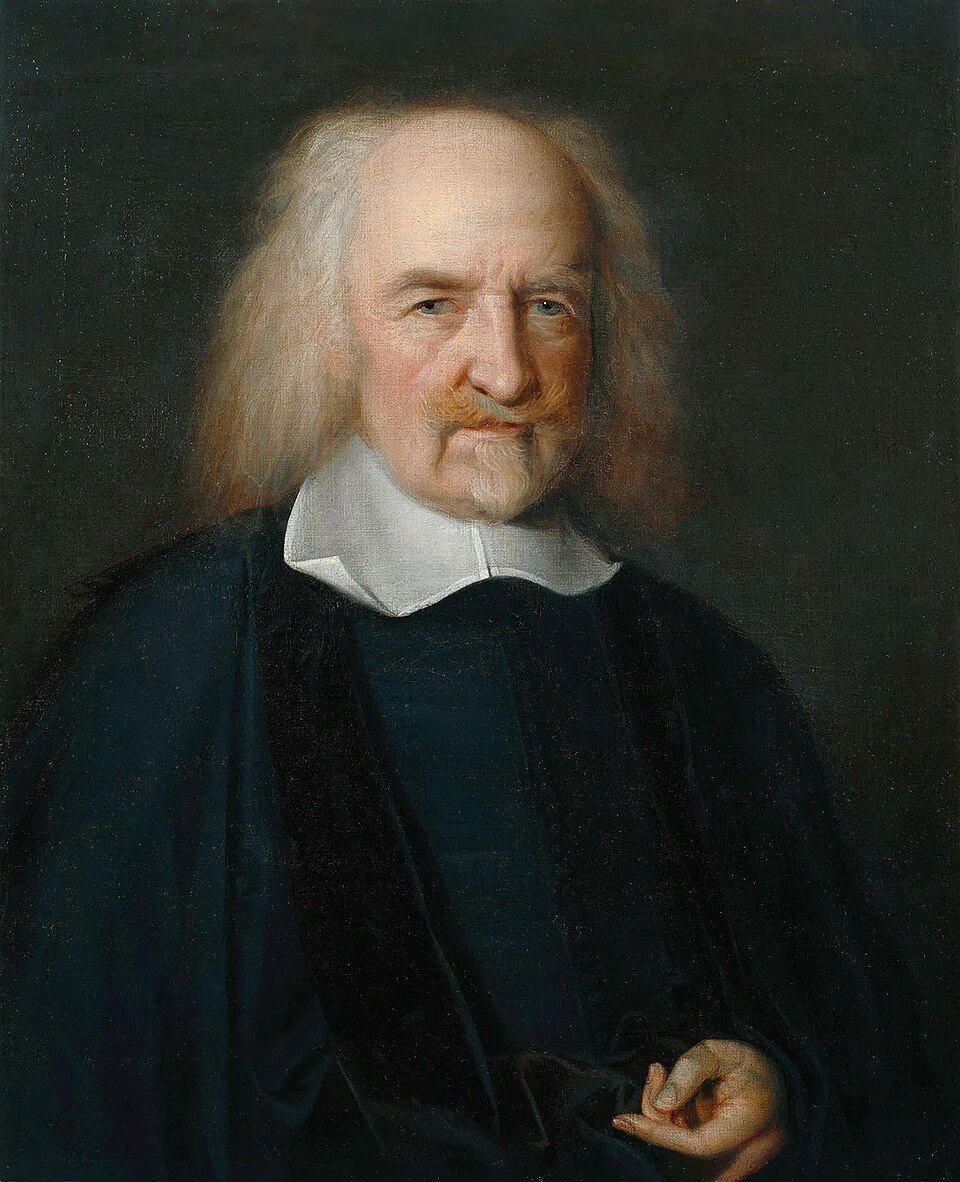

Thomas Hobbes’ (1588-1679) theory of social justice was one of the first theories that did not rely on religion (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Hobbes viewed people as pessimistic and negative. Hobbes espoused that if people did not have a system of checks and balances to account for their negative behaviors, they would live in a constant warlike state, always against each other (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Hobbes believed that people would never choose to work together without an obligation or unless forced to do so. Hobbes felt that if society had a set of rules to abide by, people would follow those rules and live in harmony. The key to this theory is that people need a larger entity to make these rules, govern their interactions, and work together (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007).

Hobbes included the theory of equity in his law of nature as well (Sorell, 2016). Hobbes tells us that people have two impressions of what equity means. The first type of equity is where a governing body determines what is fair and equal. This looks like a judge having a decision to make regarding which person in a situation is equal and just: they would follow the stated purpose of the law. The other type of equity is when people submit to using the theory of personal judgment when placed in a controversy (Sorell). This means people will favor one side of a controversy over another based on their personal biases and feelings. These different definitions of equity, as explained by Hobbes, are the foundation for his social justice theory.

Discussion Questions

- Can you think of a time when you were forced to choose a side?

- How did your personal bias play into the choice you made?

- Looking back, was your choice equitable?

John Locke’s (1632-1704) theory of social justice is similar in nature to Hobbes’ theory in that social justice is seen as a type of social contract between people. The difference is that Locke’s theory does not have the same negative view of society. Locke explains that while people need some type of contract and agreement to work together, they are obliged by their moral foundations, which are rooted in their belief in God, to respect each other (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). A larger governing entity can support this, but Locke focused on a person’s internal moral compass. This moral compass leads people to healthy interactions with fellow community members. An example given by Locke is as follows: God has given people the earth and the use of its resources for survival and comfort. When a person mixes their own personal labor with the God-given resource of land, they have made it their privately owned property (Munger et al., 2016). An example of this philosophy would be homesteading during westward expansion in the United States. Homesteaders put labor into their land and, thus, believed that God granted them this resource (Riddle, 2010). Locke suggests limiting the act of turning resources into property to ensure equity over distribution (Munger et al., 2016).

Both Hobbes’ and Locke’s theories identify the importance of having a third party to determine if an inequity or imbalance exists. Thus, when an individual feels deprived of a right, they can take this dispute to a larger governing entity for resolution (Crawford, 2020). Both philosophers advocate for government as a part of moral decision-making.

Discussion Questions

- How might this kind of philosophy work in the current world?

- How might this kind of philosophy not work in the current world?

- What are the risks of assigning the government to make decisions about morality?

David Hume’s (1711-1776) theory of social justice argued that the only real form of justice is guaranteed by having a larger entity, like a government, have power over the balance (Munger et al., 2016). Hume focused on politicians and rules as the driving factors behind what makes people treat each other morally. If a person is unwilling to follow the rules set forth by the government or politicians, that person is at risk of damaging their reputation. This is part of what Hume believed is necessary or drives people to follow the government-set rules. He identified justice as a “sense of common interest” that people feel in their moral self and how others view them (Coventry & Sager, 2013).

Jean Jacques Rousseau’s (1712-1778) theory of social justice is rooted in the idea that community is what creates the action of social justice (Munger et al., 2016). Living and being a part of a community creates an unspoken social contract between the members. This social contract gears people to act as though they need to oblige each other and share living resources. This is the opposite of basic human nature, which, according to Rousseau, is to survive and focus on self-preservation (Munger et al., 2016). The existence of a social contract is when people consider the well-being of others and then distribute goods in a manner that will benefit others. Rousseau’s theory is very similar to that of Locke in their understanding of a social contract existing between people (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007)

John Stuart Mill’s (1806-1873) theory of social justice stems from a belief that people’s sense of justice is rooted in our internal consciousness (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). This internal consciousness guides our actions and beliefs in how we interact with each other. Mill believed that people behave in ways that bring them happiness. If this behavior does not impact anyone, people have the right to act on their wishes and wants. However, if the behaviors or actions people want to engage in may negatively impact another person, people do not have the right to engage in this behavior. Mill stated that when a conflict exists between the behavior we want to engage in and its potential consequences, society needs to follow a utility principle of following a just path (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). This means respecting the happiness of others and allowing them to perform such acts that bring them happiness, until it harms others.

Mill had three principles of justice when it came to the distribution of goods. The first was that a person has a right to the goods produced by their labor. The second is that people deserve compensation when they invest their own money, as they are benefiting society on a larger scale. Mill’s third principle of equal distribution is that people have a right to property gifted to them (Nathanson, 2012).

Discussion Questions

- How do these three principles apply today?

- What would you add to Mill’s three principles of justice regarding the distribution of goods?

- Where might individuals who struggle with poverty fit into this definition?

Karl Marx’s (1818-1883) theory of social justice had similar approaches, with social justice being strongly connected to the economy and its structure (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Marx believed that justice was a tool used by the ruling upper class of society to hide the true missions of the capitalistic economy (Munger et al., 2016). He believed that rather than the existing market creating and producing justice naturally, the market itself (and those who controlled it) produced injustices regarding goods and their distribution (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007). Marx believed that the only way to do away with these injustices and unequal distribution of goods was to do away with the concept of a capitalist market. This did not mean that capitalism was fully unnecessary, rather he believed that capitalism was a necessary part of our development as a human race. It meant he believed it should be seen as a phase of our growth and be left behind for a more equitable system to take its place. This more equitable social justice system would turn away the ideals that material goods are the basis of society (Munger et al., 2016).

Postmodern Theories

Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844-1900) theory of social justice is rooted in class and power. Nietzsche believed that laws and rules were created by a particular set of people who held societal power (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007) and believed that the concepts of morals and ethics reflected an artificially created set of rules. He believed that pure justice exists only between two groups of equal power. According to Nietzsche, the development of social justice rules is done in two parts. In the first part, competing power groups create rules over the weaker groups. Inequalities then develop as the powerful group sets societal rules. The second part is focused on pity towards weaker groups stemming from Christian ideals. The weaker, less powerful groups then need to organize and create conflict with the stronger, more powerful groups to balance out power (Capeheart & Milovanovic, 2007).

John Rawls’ (1921-2002) theory of social justice focuses on social disparities. The Rawlsian theory believes that large institutions perpetuate deep-seated inequalities that offer certain individuals privileges over others (Munger et al., 2016). This theory states that for justice to be present, there must be an equal distribution of goods, opportunity, and money in society. Without this equal distribution, social justice does not exist. Rawls created two principles to ensure social justice. The first principle is the Fair Equality Principle. This principle gives equal rights and basic liberties to all society members. The second principle is the Different Principle. This principle calls for a fair distribution of social goods, avoiding exchanges between economic/social gains and basic human liberties (Munger et al., 2016).

An example of Rawls’ second principle also applies today. Consider affirmative action. It was identified that there were disparities in who could receive education based on ethnic background, and affirmative action was enacted to create a fair distribution of education.

Video: Is Affirmative Action Fair? by Above The Noise.

Discussion Questions

- What are the goods involved when discussing affirmative action?

- Does affirmative action create a fair distribution of goods? How?

- Now that affirmative action has been overturned, how are college admission processes going to change? What can they do to maintain equity in the admission process?

Current Theories

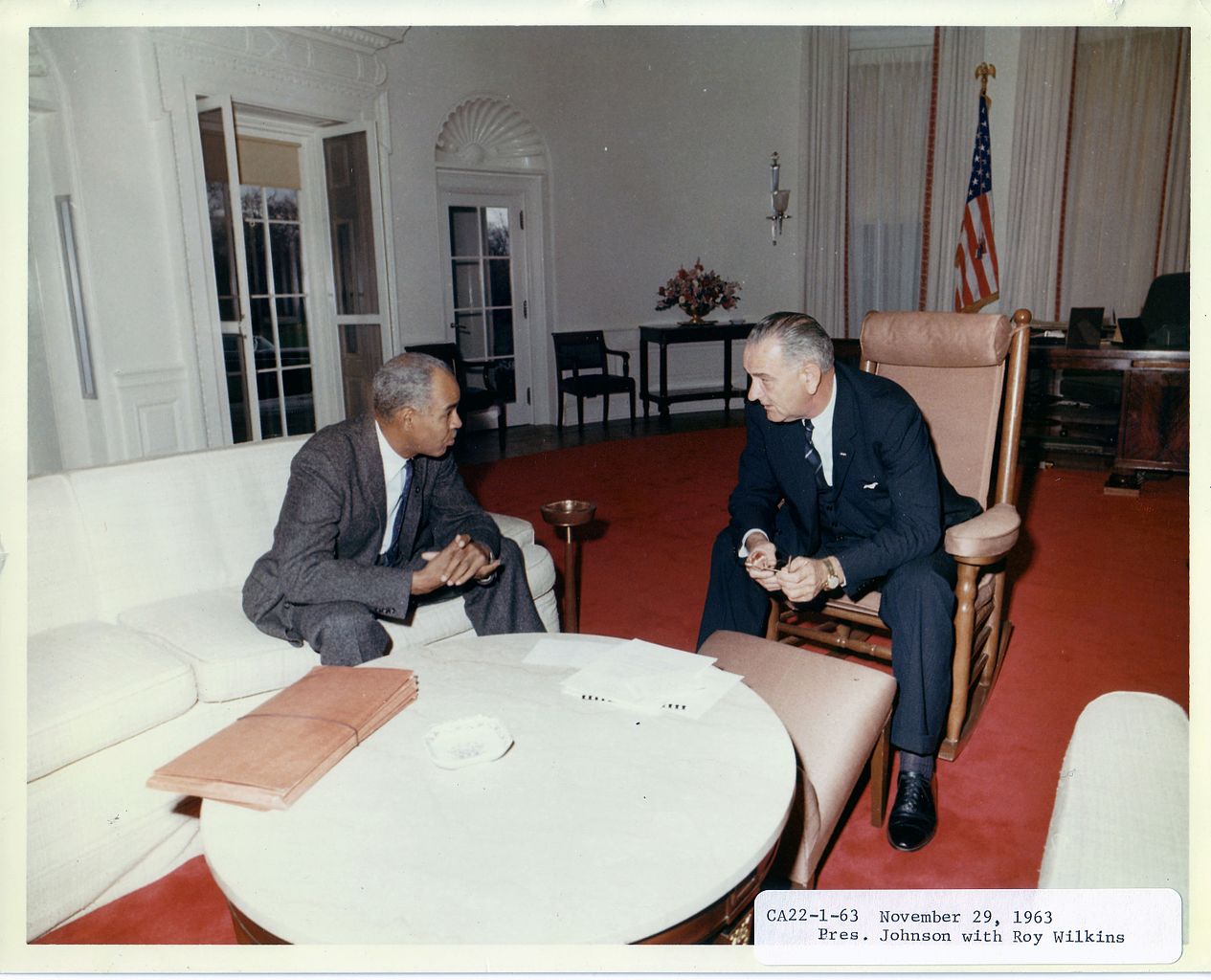

Roy Wilkins’ (1901-1981) theory of social justice. Roy Wilkins held leadership roles in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) as the Executive Secretary and Executive Director from 1955 until 1977 (Ryan, 2014). Wilkins often spoke on instilling racial pride, supporting Black history, and integrating education, which differs from state to state (Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities, n.d.). While Wilkins is best known as a civil rights advocate, he used his journalism career to advance social justice as well. Wilkins was the first Black newspaper columnist in the syndicated, mainstream press. Wilkins used his platform for journalism to spread information regarding “denouncing black criminal acts and to encourage Black Americans to support law enforcement” (Bedingfield, 2019, para. 4).

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s (1929-1968) theory of social justice focused on mass civil disobedience. This theory came about due to the White backlash of Black Power movements and from issues that arose when attempting to move forward with acts of liberation and taking back power (Livingston, 2020). Dr. King often referred to justice as a concept that “ought” to be rather than “is.” He viewed the civil rights movement as a morally focused attempt to adjust and fix an unjust relationship (Lee, 1984). Dr. King’s work paved the way for many modern-day social justice activists.

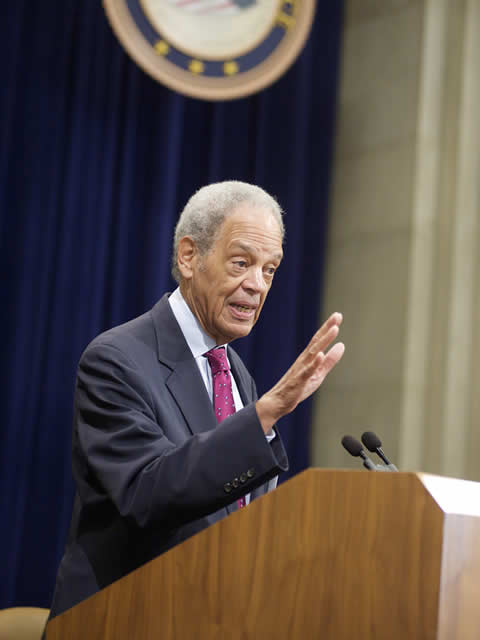

Roger Wilkins’ (1932-2017) social justice theory. Roger Wilkins was a lawyer, civil rights leader, journalist, and professor who served as the Assistant Attorney General of the United States from 1966-1969. He brought the Black Power movement to the presidential office during this time. The goals of the Black Power movement were focused on Black politics and economic power. Wilkins believed in promoting racial pride and Black economic empowerment and promoted the Black Power movement as a positive and necessary strategy to continue the forward movement of civil rights. Wilkins fought for Black Power to show the country how “black middle class success and growing disadvantage for power and working-class African Americans” (Davies, 2017, p. 3) reveal the power and strength of White interest.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1959- living) theory of social justice is heavily influenced by contemporary feminist and antiracist concepts. Crenshaw states that to overcome racist and patriarchal shadows, the victims of political and social crimes must make their circumstances known (Crenshaw, 2005). Crenshaw’s theory relies heavily on the construct of intersectionality.

The concept of intersectionality describes the ways in which systems of inequality based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, class and other forms of discrimination intersect to create unique dynamics and effects. For example, when a Muslim woman wearing the Hijab is being discriminated, it would be impossible to dissociate her female from her Muslim identity and to isolate the dimension(s) causing her discrimination. (Lawrence Hall, 2022, para 4)

In an interview with Crenshaw at Columbia Law School in 2017, she identified intersectionality as “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects” (Columbia Law School, 2017, para. 4). Other examples of this include how transgender people of color report increased experiences of abuse in our medical system compared to patients who identify as White and straight, or how Latinx women earn lower wages and are overrepresented in jobs that are known to offer lower wages, especially when compared to White women (Heyl, 2023).

Video: The urgency of intersectionality by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Discussion Questions

- How do you see intersectionality represented in your community?

- How do you see intersectionality represented in your classes?

Dr. Green here. I spoke with Dr. John Watts about the concept of intersectionality for the purpose of this chapter so I could learn more about it. Dr. Watts is a former probation supervisor for the State of Connecticut and currently an Assistant Professor and the Program Director for the Criminal Justice and Restorative Justice Program at the University of Saint Joseph in West Hartford, Connecticut, and a Certified Criminal Justice Addictions Counselor. Dr. Watts explained:

When I think about intersectionality, the first thing that comes to mind is the overlapping systems of oppression. For instance, someone can be African American and identify as gay or lesbian; that particular individual can be exposed to societal racism based on their skin color and homophobia based on their sexual orientation at times from their own race or culture. As a response to those overlapping systems of discrimination/oppression, many marginalized groups learn how to “code switch.” Code switch is a way to navigate those overlapping systems of discrimination/oppression. Code-switching can be very exhausting because the marginalized individual is constantly trying to assimilate in and out of different situations/systems, thus losing a part of their identities.

In my profession, I had to learn how to code-switch in order to be promoted to a Chief Probation Officer. Currently, I’m one of only four Black male supervisors in the entire probation department. Even in our probation department, Black males are seen as over-aggressive, angry, and lacking the skills to be in a leadership position. So, in order to move up in the department, I knew I needed to work to offset those negative stereotypes of Black males, which propelled me right into my doctoral degree (J. Watts, personal communication, July 25th, 2023).

- What type of intersectionality do you see in your career?

- How do you navigate intersectionality in the workplace?

- How does intersectionality impact your ability to do your job?

- How is intersectionality reflected in today’s politics? Supreme Court decisions?

Rose Braz’s (1961-2017) theory on social justice stemmed from a grassroots movement to connect climate, environment, social justice, labor, and faith in working together to better serve the people (Center for Biological Diversity, 2023). She believed the first step in making any change is to name it clearly (Bennett, 2008). Much of Braz’s social justice work centered around prison reform and challenging the currently existing criminal justice structure (Braz et al, 2000). Braz and her supporters followed specific, intentional steps to impact social justice reform. They started with gathering members, then moved on to having regular meetings, choosing a focus, seeking publications to support the cause, and working together on steps toward the right direction (Braz et al., 2000).

Critical Race Theory (CRT)

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a newer concept in the field of social justice. CRT began in the 1970s in the wake of the civil rights era. Many people attribute the beginning of CRT to Malcolm X (Rabaka, 2002). Malcolm X, originally named Malcolm Little, was born in 1925 and died in 1965 (Assensoh & Alex-Assensoh, 2014). Malcolm X expressed that our society was “undergoing a radical process of change and development” (Rabaka, 2002, p. 146). Some of the points that he focused on included the fact that Black Americans have been impacted, influenced, and corrupted by imperialism, which interrupted Black history. An essential aspect associated with the evolution of CRT is the utilization of the lived experiences of Black people to criticize the discrimination they face, which can serve as a basis for striving toward liberation (Rabaka, 2002).

Many individuals played significant roles in the continued growth and development of CRT. Writers and theorists such as Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, and Richard Delgado saw a need for a new movement to continue forward progression. CRT is a movement supported by activists and scholars, which is focused on transforming the relationship between race, racism, and power (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017). CRT speaks to concepts from the civil rights movement and ethnic studies and then adds a broader perspective that “includes economics, history, setting, group and self-interest, and emotions and the unconscious” (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017, p. 3).

Racism has been created systematically in the United States. It has been embedded in society, laws, policy, and institutions for hundreds of years and continues to be a struggle today. CRT posits that racism is normal and the usual way our society behaves, and it is a regular, everyday experience for people of color. In addition, society is geared towards supporting the White population as the dominant group. CRT believes in social constructivism, which means that they see race as the product of social thought, not as a fixed, scientific construct. Today, CRT can be seen in multiple ways: the Latinx-critical movement, queer-crit (LGBTGEQIAP+) studies, and thinkers challenging how we conceptualize equality, civil rights, and national security (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017). These movements challenge the status quo to make forward-moving change.

Video: “Indigenous in Plain Sight” by Gregg Deal.

Discussion Questions

- How do or can we use history to support and move forward in social justice?

- What theories can explain Gregg’s experiences? Where does his story fit into the content you learned in this chapter?

DisCrit Theory

DisCrit Theory, or Disability Critical Theory, provides insight into where racism and ableism intersect (Love & Beneke, 2021). It focuses on how the forces and power of racism and ableism exist independently and are often neutralized for the public to upload a certain sense of normalcy (Connor, et al., 2021). The goal of DisCrit theory is to support people in valuing their multidimensional identities. By considering the legal and historical aspects of disability/ability and race, people can better understand how the Western cultural norms have oppressed individuals living in this crosshair (Connor et al., 2021).

Video: Changing the way we talk about disability by Amy Oulton.

Discussion Questions

- After watching the TedTalk by Amy Oulton, what is one way you can change the way you react to or talk about disability/ability?

- Why is it important that we work to change the way we think and talk about disability/ability?

Thoughts from the Authors

I wanted to share my personal experience with writing this chapter. After my first draft, I felt this chapter was the easiest for me to write. All I had to do was search through history and summarize some past social justice theorists…that is, until my wonderful colleagues and peer reviewers alerted me to the Whitewashed history that I was sticking to. Once I was made aware of this, something that I was so used to reading, I really had to dive deep to uncover and share crucial theories of social justice that are not shared in mainstream history books. This is a perfect example of the vital importance of peer review and collaboration. History is written by the winners and those who take the time to put pen to paper. If we want to change what we read in history books, we need to be the ones to write our ideas and concepts down to save them for future generations to read. This is also a place where I would like to invite you to connect with me and share other theorists and theories that you feel should be discussed. I would love to update this chapter to reflect how social justice has developed and played out over time.

Sincerely,

Dr. Green

For me, the theories begin by defining what social justice is and evolve into recognizing what social injustice is. That seems to be the driving force behind change. As a psychologist, change is a desired result. My clients come to me because they desire some kind of change, whether it be changing how they feel about something, how they think about something, or how they do things. Frequently, it is that they want someone around them to change. I tell them all that without distress, there is no change. So, even if they’ve come to me in distress and want to do something new or different, wanting to change for someone else is quite challenging. If that person feels no distress about what they are doing, they won’t change or do anything differently. I think that is what makes it so interesting to look at how these theories develop. What is the distress that leads to the shift? How does that distress get identified in others so that change occurs? Important questions that we all grow from.

Sincerely,

Dr. Brayton

- Which theorists are most relevant to today’s social justice climate? Provide examples to support your choice.

- What are some common themes amongst the theorists outlined? Why do you think these common themes have lasted into today?

- The more modern theories address how change occurs. How is this supported by or different from the earlier theories, such as social justice being based on natural law (Aquinas) or social contract (Locke)?

- What are some of the stressors that have led to the development of modern theories?

- We see a repeated theme of God and church in historical theories; why do you think this is? Where does religion fit into a discussion of social justice theories?

References

Assensoh, A. B., & Alex-Assensoh, Y. M. (2014). Malcolm X: A biography. Greenwood.

Bedingfield, S. (2019). The journalism of Roy Wilkins and the rise of law-and-order rhetoric, 1964-1968. Journalism History, 45(3), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00947679.2019.1631082

Bennett, H. (2008, July 11). Organizing to abolish the prison-industrial complex. Dissident Voice. https://dissidentvoice.org/2008/07/organizing-to-abolish-the-prison-industrial-complex/

Braz, R., Brown, B., DiBenedetto, L., Gilmore, C., Hunter, D., Parenti, C., Rodriguez, D., Shaylor, C., Stoller, N., & Sudbury, J. (2000). The history of critical resistance. Social Justice, 27(3), 6–10.

Capeheart, L., & Milovanovic, D. (2007). Social justice: Theories, issues, and movements. Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813541686

Center for Biological Diversity. (2023). Rose Braz in memoriam. https://biologicaldiversity.org/about/staff/rose_braz.html

Columbia Law School. (2017). Kimberle Crenshaw on intersectionality, more than two decades later. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

Connor, D. J., Ferri, B. A., & Annamma, S. A. (2021). From the personal to the global: Engaging with and enacting DisCrit Theory across multiple spaces. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 24(5), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2021.1918400

Coventry, A., & Sager, A. (2013). Hume and contemporary political philosophy. The European Legacy, 18(5), 588–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/10848770.2013.804709

Crawford, C. (2020). Access to justice for collective and diffuse rights: Theoretical challenges and opportunities for social contract theory. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 27(1), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.2979/indjglolegstu.27.1.0059

Crenshaw, K. W. (2005). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Cahiers du genre, 39, 51–82.

Davies, T. A. (2017). Mainstreaming Black Power. University of California Press.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: An introduction (3rd ed.). New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1ggjjn3

Heyl, J. C. (2023). What is intersectionality? Race and social justice. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-intersectionality-7097945

Kamtekar, R. (2001). Social justice and happiness in the republic: Plato’s two principles. History of political thought, 22(2),189-220.

Lawrence Hall. 2022. The Intersectionality of Race, Sexuality and Gender. retrieved from https://lawrencehall.org/news/brave-conversations-intersection-of-race-sexuality-and-gender

Lee, S.-H. (1984). The concept of justice in the political thought of Martin Luther King, Jr. Journal of East and West Studies, 8(2), 43-64.

Livingston, A. (2020). Power for the powerless: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s late theory of civil disobedience. The Journal of Politics, 82(2), 700–713. https://doi.org/10.1086/706982

Love, H. R., & Beneke, M. R. (2021). Pursuing justice-driven inclusive education research: Disability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) in early childhood. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 41(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121421990833

Munger, F., MacLeod, T., & Loomis, C. (2016). Social change: Toward an informed and critical understanding of social justice and the capabilities approach in community psychology. American Journal Community Psychology, 57(1-2), 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12034

Nathanson, S. (2012). John Stuart Mill on economic justice and poverty. Journal of Social Philosophy, 43(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2012.01556.x

Rabaka, R. (2002). Malcolm X and/as critical theory: Philosophy, radical politics, and the African American search for social justice. Journal of Black Studies, 33(2), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193402237222

Riddle, M. (2010). Donation Land Claim Act, spur to American settlement of Oregon Territory, takes effect on September 27, 1850. History Link. https://www.historylink.org/file/9501

Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities. (n.d.). Roy Wilkins. Who Speaks for the Negro: An Archival Collection, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. https://whospeaks.library.vanderbilt.edu/interview/roy-wilkins

Ryan, Y. (2014). Roy Wilkins and the civil rights “crisis of unity.” Social Policy, 44(1), 46–53.

Scholz, S. J. (2006). Civil disobedience in the social theory of Thomas Aquinas. Routledge.

Sorell, T. (2016). Law and equity in Hobbes. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 19(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2015.1122353

Tillman, M. (2021, November 12). What’s the difference between classical, modern and postmodern philosophy? Friendly Philosophy. https://micahtillman.com/clasicalmodernpostmodern

Media Attributions

- Plato © Photo by: Ricardo André Frantz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Aristotle © After Lysippos is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Thomas Hobbes © John Michael Wright / NPG is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Roger Wilkins © Photo by Lonnie Tague for The Department of Justice is licensed under a Public Domain license

- LBJ with Roy Wilkins © LBJ Library is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kimberlé Crenshaw © Mohamed Badarne is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

About the authors

name: Cailyn F. Green

Cailyn F. Green is a Certified Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Counselor- Masters Level (CASAC-M) through New York State. She is the Addiction Studies Professor at the State University of New York: Empire State University. She earned her BA from Western New England University in Springfield, MA and her MS in Forensic Mental Health from Sage Graduate School in Albany, NY. Her Ph.D is in Criminal Justice, specializing in Substance Use from Walden University in Minneapolis, MN. Dr. Green has over 10 years of experience teaching both in online and in-person college-level settings in substance use, human service, criminal justice and clinical counseling topics. She won the Scholars Across the University award in 2024 for her research in substance use topics and this social justice-focused textbook. She has 9 journal article publications to date and her other published textbooks include Evidence-Based Substance Use Treatment and the Group Counseling Workbook.

name: Kim Brayton

Dr. Brayton received a joint law and clinical psychology doctorate in California at Palo Alto University and Golden Gate School of Law. She is a professor at Russell Sage College where she heads the program working with students in forensic mental health. Additionally, she has a private practice where she specializes in treating adult survivors of trauma and forensic assessment. In her spare time she enjoys golf, reading and the various exotic locations she bikes through on her stationary bike.

name: Bernadet DeJonge

Bernadet (Bernie) DeJonge, PhD, CRC, LMHC, has her BA in psychology (1999) and MA in Rehabilitation Counseling (2007) from Western Washington University. Her PhD is from Oregon State University in Counseling (2022). She is currently an Assistant Professor in the School of Human Services at Empire State University. Bernie’s areas of interest include DEIB, the integration of counseling into medical services, online pedagogy, and disability.