14 Social Justice Practice in Human Services: An Individual Approach

Cailyn F. Green; Kim Brayton; Carrie Steinman; and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will understand the role ethics play in working in the human service field.

- The reader will analyze how different types of personal bias impact human service professionals working in the field.

- The reader will describe how diversity issues exist within assessment practices.

The human services profession has always served culturally diverse populations in the United States. Early involvement in social issues demonstrates a commitment to social justice and advocacy to end discrimination, oppression, poverty, and other forms of injustice throughout the country’s history (Sue & Sue, 2016). As human services professionals, we must recognize how individual and historical power and privilege may prevent us from understanding our clients’ experiences and views.

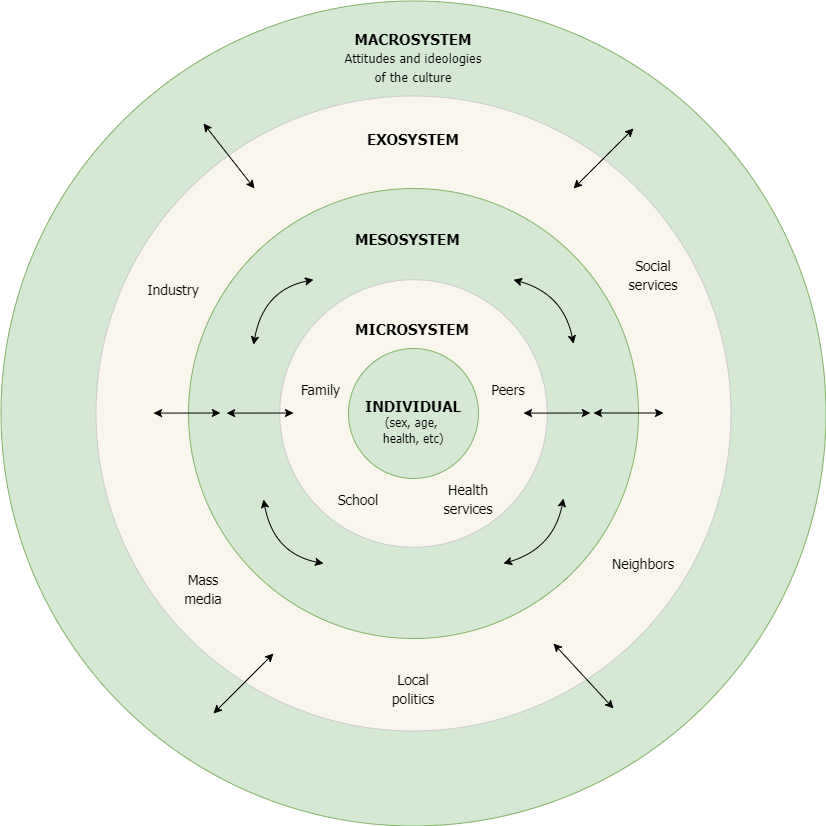

In the human services field, professionals work with clients on various levels. Often, these levels are viewed through a systems lens. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) systems theory, also known as the ecological systems theory, posits that different environmental systems influence the people we serve in the human services field. This theory identifies five systems that interact to shape individual development: the microsystem (immediate surroundings like family and school), the mesosystem (interactions between microsystems), the exosystem (external environmental settings that indirectly affect the individual), and the macrosystem (broader cultural and societal influences). The chronosystem (the dimension of time encompassing life transitions and historical events) was recently added to the model. Bronfenbrenner’s framework emphasizes the dynamic interplay between these systems and highlights the importance of considering multiple environmental contexts in understanding human growth and development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Understanding the interactions between systems is essential in identifying the roles of power, privilege, and oppression in human services. Once we have identified how power, privilege, and oppression impact clients, we can look toward equitable change in the field. This chapter will focus on the microsystem and examine individual social justice experiences in human services.

Ethics and Social Justice

One of the core foundations of the human services profession is understanding our ethical responsibilities. Ethics is the study of what is right and wrong and how we make decisions when that choice is unclear. Many professions, such as counseling, social work, direct support professionals, and human services, have established ethical codes of conduct to help. The National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) provides an ethical code of conduct for those working in the Human Services field to follow (NOHS, 2024).

There are different ethical codes for various helping professions. As this is a chapter for human services students, we will focus on the National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) code. However, we are sharing some that might also be applicable as students continue in their helping careers.

- NOHS Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals (2024)

- American Counseling Association Code of Ethics (2014)

- National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics (2021)

- National Alliance for Direct Support Professionals (NADSP) Code of Ethics (2000)

Discussion Questions

- Compare and contrast the different codes—what is similar? What is different?

- Why might it be useful in human services to examine the ethical codes of different professions?

- How can you use ethical codes to make ethical professional decisions?

NOHS Ethical Code in Practice

The National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) has developed an ethical code of conduct for human services professionals (NOHS, 2024). The Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals outlines standards for human services work to establish professional boundaries and facilitate healthy, appropriate client relationships.

Multiple NOHS ethical codes apply to social justice in human services. Standard seven states: “Human service professionals ensure that their values or biases are not imposed upon their clients” (NOHS, 2024, para 11). Additionally, the NOHS ethical code calls out the responsibility of human services workers to be self-aware. This includes awareness of how social and political issues may disenfranchise and impact clients. Standard 14 states: “Human service professionals are aware of social and political issues, comprehend their effects on clients, and recognize how the impact of such issues vary among individuals from diverse backgrounds,” (NOHS, 2024, para 18).

As ethical practitioners, human service professionals must examine their values and how they impact client relationships. Most ethical decision-making starts with an examination of values. This foundation for personal and professional choices profoundly impacts client services. All human service professionals have personal and professional values that can affect their work, and recognizing the similarities and differences between personal, professional, and client values is an important skill (Kenyon, 1999). In addition, boundaries are essential in the professional relationship, and if a human services worker does not maintain appropriate professional boundaries with their clients, power differentials become more apparent.

Can you identify what your values are? Having a solid sense of values is essential in the human services field. One of the ways human services workers can examine our values is by completing a card sort. Look at the cards listed at motivationalinterviewing.org and sort out what cards are Important, Very Important, and Not Important to you. Then, choose your top five values from the choices.

Discussion Questions

- Did you find any values missing from the sort? What were they?

- Was it hard to choose a top five? Why do you think that is?

- What do the values you chose say about who you are as a human services worker?

- What do the values you did not choose say about who you are as a human services worker?

- How might knowing your values help when you conflict with someone else?

The human service professional has multiple responsibilities to their clients around social justice issues. The NOHS ethical code clearly states that supporting and developing a relationship with a client should be based on social justice principles. It outlines that human services workers must understand cultural norms within the client’s community and integrate them into their practice (Hays & Erford, 2018). Ethical human services workers acknowledge the impact of social justice issues by respecting diversity and difference and ensuring inclusion and accessibility to all. Human services workers make a transparent and open effort to foster equity in all client interactions (NOHS, 2024).

Human service professionals also have a responsibility to their employers. Statements 33 and 34 discuss providing clients with high-quality services. Workload issues are a common problem in human services, and it is unethical to allow excessive workload to result in poor services, particularly since the clients we serve are often marginalized. Additionally, statement 34 states: “When a conflict arises between fulfilling the responsibility to the employer and the responsibility to the client, human service professionals advise both and work conjointly with all involved to manage the conflict” (NOHS, 2024).

The Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS, 2020) in New York State uses policy to ensure equitable services. They developed a policy that their substance use treatment outpatient facility will monitor and assign cases to “ensure that all clients can expect quality treatment” (pg. 8). OASAS outlines how the intensity of treatment for each case should be a determining factor in assigning cases amongst the case managers. As human service workers, our workload requirements and high caseload often affect our client work. Our ethical obligation is to resolve this issue if it negatively impacts our clients.

Note from the author:

While evidence-based best practices and clinical standards exist to maintain equity amongst treatment, there is also a reality outside these guidelines. When I was working in an outpatient substance use treatment facility, the reality was that we had such a high number of clients seeking support that we had to take on cases that might have been intense for our already high caseload. Since many of our fellow outpatient facilities in the area had similar issues, we worked together to move clients around the best we could, but sometimes, there needed to be somewhere to refer to them. In these situations, we followed evidence-based best treatment practices in our groups and individual sessions to provide each client the highest quality of treatment. Sometimes the reality is a human service professional gets bigger caseloads than they can realistically handle. When this happens, what should we do as human service professionals?

-Dr. Green

Video: Service with a Smile by Laura Hockenbury, TEDxBoulder

Discussion questions

- How does this video connect to how we, as human service professionals, can properly distribute our time without burning out?

- How may burnout impact our ability to work effectively with clients who present with unique diverse situations that we are not personally aware of?

Personal Bias in Human Service Practice

Human services professionals are responsible for cultivating inclusivity and must be aware of personal biases and how they impact professional interaction (Hays & Erford, 2018). Biases are ingrained thoughts or feelings stemming from past experiences that significantly influence our actions and decisions. In general, biases are unconscious or implicit, and people are unaware of them. As Ross (2020) articulates in his book Everyday Bias, “If you are human, you are biased” (p. 1). This statement underscores the universality of bias, highlighting that everyone harbors some form of bias regardless of their background. Ross further elaborates that these biases can manifest in various ways, both constructive and detrimental. He explains that positive biases can sometimes lead to favorable outcomes, while negative biases can result in harmful consequences. Thus, the impact of bias is multifaceted, influencing our personal and professional perceptions and interactions in various ways (Ross, 2020). Understanding this dual nature of biases is crucial for fostering greater self-awareness and promoting fairer, more equitable services in the human services field.

Discussion Questions

- Ross (2020) states, “If you are human, you are biased.” How do you interpret this statement, and what implications does it have for self-awareness and personal growth in pursuing social justice in human services?

- Can you think of a situation where a positive bias had a constructive outcome in advancing social justice? Conversely, can you provide an example where a positive bias led to negative consequences that hindered social justice efforts?

- What strategies can individuals employ to identify and mitigate their own biases, both positive and negative, to promote social justice and more equitable interactions in human services?

Before discussing how biases impact the human services field, let us define a few biases. Here are a few of the primary types of biases we regularly experience:

Affinity bias—We tend to prefer people more like us. If the group you identify yourself to be in is one with power or privilege, the affinity bias is stronger. When a decision is made which was impacted by affinity bias, it can interfere with people’s work lives, personal situations, education settings, and social situations (Ricee, 2023).

Attribution Bias—Making judgments or assumptions about someone based on their appearance or behavior. This often occurs when we evaluate other people’s behaviors based on our behaviors or cultural norms (Hurd, 2018).

Beauty bias – When an individual prioritizes others with cultural beauty characteristics (Maccarone, 2003). As beauty is defined by culture, what everyone defines as “beautiful” may differ.

Conformity Bias—This is “group think,” the idea that when we are in a group, we are more likely to do things we may not do on our own (The University of Texas, 2024). Thus, we conform to the norm of the group.

Confirmation Bias—The tendency to favor and seek out evidence that supports preexisting beliefs, while ignoring or dismissing contradictory information. This often leads to individuals giving more weight to evidence that supports their views and downplaying evidence that does not (Casad & Luebering, 2023).

Contrast Effect—This bias occurs when people are compared to each other (Caccavale, 2020). Rather than seeing an individual based on their own merits, they are seen only in comparison to others. “Our perception is altered once we start comparing things to one another” (Caccavale, 2020, para. 2). This contrast effect can occur in two ways, positive and negative. A positive contrast effect is when someone is seen as better than someone else. A negative effect is when someone is seen as worse than someone else (Caccavale, 2022).

Gender Bias – This bias favors one gender over another, often resulting in unfair treatment towards individuals based on their gender. Unconscious gender bias can present itself in subtle ways (American Psychological Association, 2023). For example, assuming that some professions are for males and some are for females.

Geographical bias – This bias occurs when a person has a distorted opinion or judgment based on geographical location (Kowal, Sorokowski, Kulczycki, & Zelazniewicz, 2022). The geographical location may be where someone was previously living, is currently living, or will be moving to in the future.

The Halo Effect—This bias occurs when we focus on one perceived good feature about someone to the exclusion of everything else. It is also sometimes referred to as the “physical attractiveness stereotype” (Cherry, 2022, para. 3). Attractiveness is a significant part of the Halo Effect; people who are considered attractive by cultural standards are often seen to be more important in society than others (Cherry, 2022).

Sexism, Heterosexism, and Trans bias—These biases appear when individuals are biased toward those who deviate from traditional gender norms and expectations. These biases often lead to heterosexism, a prejudice that factors opposite-sex relationships and the belief that heterosexuality is superior to homosexuality (Centers for Disease Control, 2023).

Social class biases—This occurs when individuals experience negative feelings about a client based on their socio-economic background and social class. This kind of bias supports inequality based on economic and social status (Durante & Fiske, 2017).

Unconscious Bias – That first thought, any feeling you may get or preconceived notions we have are all personal biases. This may be based on a client’s clothing, skin color, smell, language spoken, or the family members they may have with them (Veesart, 2020). Having them does not make us bad people; it simply makes us human. The goal is not to allow these unconscious, personal biases to influence the way we interact and make decisions for our clients.

Video: How to Overcome Our Bias by Verna Myers

Discussion Questions

- What does it mean to “walk boldly towards” our biases, and why is this approach important in overcoming them?

- According to the video, why do biases persist even when we consciously try to avoid them? How can awareness of this phenomenon help in addressing biases effectively?

- Discuss the concept of “bias literacy” introduced in the video. How can developing this literacy help us to be better human services professionals?

- In what ways does the concept of “walking boldly towards biases” align with principles of social justice? How can addressing biases contribute to advancing social justice goals in human services?

- Considering the insights from the video, what steps can individuals take today to start addressing their biases and fostering a more inclusive mindset? How can these actions create ripple effects in promoting fairness and equality in human services?

Assessment and Social Justice

One of the tasks of human services is to administer standardized assessments and screening tools. Examples of screening tools used in human services include the PHQ-9 for depression, the GAD-7 for anxiety, the ACES questionnaire to look at childhood trauma, the CAGE questionnaire to identify drug and alcohol use, and the Mini-Mental Status Exam, which looks at cognitive functioning in adults. These screening tools help human services professionals in various fields, such as social work, counseling, healthcare, and education, to identify potential issues, assess client needs, and guide appropriate interventions and treatment plans. Screenings in human services are selected based on the population being served and should be informed by evidence-based best practices. Screening and assessment play a crucial role in developing personalized treatment plans and ensuring that individuals receive the support and services required to improve their quality of life (Mulvaney-Day. et al, 2017).

Assessment and screening tools often contain significant biases. Social justice issues arise not only from the personal bias of human service professionals in interpreting answers but also from bias in the screening tools themselves. Some contextual factors that have the potential to cause bias in a screening or assessment tool include racialized identity and ethnicity, discrimination, neighborhood context, trauma, immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and a client’s age (Bridgwater, 2023).

Reynolds and Suzuki (2012) identify seven specific categories when it comes to potential consequences of bias in screening tools:

- Inappropriate content. Tests are geared to majority experiences and values or are scored arbitrarily according to majority values. Correct responses or solution methods depend on material that is unfamiliar to minority individuals.

- Inappropriate standardization samples. Minorities’ representation in norming samples is proportionate but insufficient to allow them any influence over test development.

- Examiners’ and language bias. White examiners who speak standard English intimidate minority examinees and communicate inaccurately with them, spuriously lowering their test scores.

- Inequitable social consequences. Ethnic minority individuals, already disadvantaged because of stereotyping and past discrimination, are denied employment or relegated to dead-end educational tracks. Labeling effects are another example of invalidity of this type.

- Measurement of different constructs. Tests largely based on majority culture are measuring different characteristics altogether for members of minority groups, rendering them invalid for these groups.

- Differential predictive validity. Standardized tests accurately predict many outcomes for majority group members, but they do not predict any relevant behavior for their minority counterparts. In addition, the criteria that tests are designed to predict, such as achievement in White, middle-class schools, may themselves be biased against minority examinees.

- Qualitatively distinct aptitude and personality. This position seems to suggest that minority and majority ethnic groups possess characteristics of different types, so that test development must begin with different definitions for majority and minority groups. (Reynolds & Suzuki, 2012, p. 87)

Some contextual factors which have potential to cause bias in a screening or assessment tool include racialized identity and ethnicity, discrimination, neighborhood context, trauma, immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and a clients age (Bridgwater, 2023).

The CAGE screening tool is a common 4-question tool used to screen clients for alcohol abuse. CAGE stands for:

- C—Cutting down

- A—Annoyance by criticism

- G—Guilty feeling

- E—Eye-openers

CAGE screening questions:

- Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

- Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover (eye-opener)?

Discussion Questions

- Which question do you think could have an issue with cultural bias? Explain your reasoning.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of using this 4-question screening tool?

- Is there room for cultural differences to be explained by the client when answering this screening tool?

Human service professionals can take a variety of steps to mitigate the harmful consequences of bias in screening tools. These steps include utilizing updated and culturally sensitive and inclusive assessments, incorporating feedback from clients on assessments into best practice, and regularly reviewing screening tools to ensure they continue to meet best practice in the field. One of the most important steps is to facilitate the use of screening tools through an interactive dialogue with the client (McClintock et al., 2021). In this, the human services professional asks the questions and discusses the answers given, versus just writing down the answers or leaving the client in a room to fill out a form. By treating assessment as a conversation, the human service professional offers the client the opportunity to explain their answers. This allows the client to incorporate their cultural differences into their explanations.

Another important step in addressing bias in screening tools and assessments is training. Staff training is essential prior to using any screening tools. Training should include discussions about cultural bias in assessment, including the specific tool being implemented (McClintock et al., 2021). This approach allows professionals to consider these issues before using the screening tool.

Bias in Assessment and Documentation

Completing an intake assessment, also known as a biopsychosocial assessment, is often one of the first tasks in setting up services. This intake assessment forms the basis for developing, implementing, and evaluating a client’s goals and progress. The human services professional collects information relevant to the client’s background and needs during intake. Biases can impact the client’s intake experience. For example, if a human service professional assumes an answer to a question and skips it, the client information in their chart or file may be incomplete. This may occur because of personal biases and preconceived notions and will result in an inaccurate assessment.

I am half White and half Mexican. However, I present as White. Many times, when forms have been filled out for me, people assume—based on appearance, education, and lack of accent—that I am White and mark that box. Thus, some of my records do not indicate my mixed-race status.

-Dr. DeJonge (Bernie)

Discussion Questions

- What kind of important details might a human services professional overlook in a scenario like the one described? How could this affect service delivery?

- What challenges might arise when administrative forms or records inaccurately reflect an individual’s racial or ethnic identity? How could this impact the quality of services or support human service professionals provide?

- How can human services professionals foster environments that validate and honor individuals’ self-identified racial and ethnic identities, regardless of how they may be perceived externally?

To promote equity and inclusivity, human services professionals must ensure that they provide clients with an environment conducive to genuine responses. Often, biases are evident in both the questions asked of a client and those that are not. Examples of this include not asking about military service if the client is female, assuming someone’s sexuality when they have stated they are married, or not asking a young student whether they have used substances or are sexually active. Additionally, documentation is a vital component for both the client and the agency, and often, reimbursement for services and accountability for the organization depends on appropriate documentation.

Charting

Human services professionals are responsible for recording client’s employment, family, medical, social, socioeconomic, and mental health information. Documentation should be balanced, nonjudgmental, and objective. A chart should always be current and contain reliable information so that any agency professional can read and understand it (Silvestre et al., 2017). The chart should also explain why the client sees the human service professional. Case notes should be written about every interaction between the professional and the client. Strong case notes allow other human services professionals to read about the client’s process thus far (Summers, 2016). The client’s chart should not contain personal feelings about the client or any judgmental comments.

Some examples of judgmental notes in a chart:

- A human services worker conducts a home visit and writes notes about how the home does not feel comfortable or ‘homey.’

- A human services worker notes that a client’s family members were “uncooperative” or “hostile” during a home visit.

- A human service professional meets with a client and makes a case note about the client’s hair being unfashionable or out of style.

- A human services worker writes in a progress note that a client’s religious practices are “strange” or “unusual.”

- A human services professional writes in a report that a client’s neighborhood is “sketchy” or unsafe.

- A human services worker notes that a client’s behavior is “loud” or “boisterous.”

- A healthcare provider notes in a medical chart that a patient’s weight or appearance is “unhealthy” or “unattractive.”

Discussion Questions

- What kind of biases are present in the examples provided?

- Discuss the potential consequences of human services professionals making subjective assessments about a client’s appearance, living conditions, or cultural practices in writing. How can these judgments affect the clients being served?

- What strategies can human services professionals employ to ensure that their documentation remains objective and free from personal biases?

- How can professionals ensure that their notes accurately reflect the experiences and perspectives of clients, particularly those from diverse cultural backgrounds or communities?

Client Biases

It is important to recognize that clients also harbor unconscious biases that may affect their perceptions of us as professionals. Clients often feel anxious or uneasy about sharing their medical, mental health, employment, social, or familial information with providers (Summers, 2016), and this may be in part due to their assumptions and biases about both the individual they are working with or the human services field in general. It is the responsibility of the human services worker to identify when a client seems uncomfortable and work to establish rapport. It is also important to remember that sharing personal information and details about one’s life can be a complicated process for many. This could be for personal, professional, or cultural reasons. In addition, many clients are in new and vulnerable situations. Even when clients feel a strong rapport with an individual human services worker, they may have negative biases around the systems they are navigating. These can develop from past negative events, things they have heard in the community, and/or biases they hold around what kind of people receive or are entitled to help when they are struggling. At times, these biases can present as hostility or frustration, making building rapport difficult. It is our responsibility to be aware of this and mitigate it professionally and within the bounds of our employment agency’s parameters.

Selina is an experienced addiction counselor and a Credentialed Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Counselor (CASAC) with a master’s degree in mental health counseling who works at a local outpatient treatment facility. Hunter is her court-mandated client. Hunter is a 26-year-old Black male who was assigned to be on Selina’s caseload after he was pulled over and cited for driving while intoxicated (DWI). Hunter faces potential jail time for non-compliance with treatment. After completing a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment with Hunter, Selina presented his case to the treatment team. The team recommended that Hunter engage in intensive outpatient treatment, which would consist of three hours of group therapy, three days a week. Hunter strongly disagreed with this treatment recommendation. During their discussion in Selina’s office, Hunter expressed skepticism about Selina’s expertise due to her lack of personal addiction experience. Hunter said directly to Selina, “You are a pretty little White girl who has never seen any problem in your whole life because daddy always got you out of every problem you ever encountered. I want a counselor like me, who has lived where I live and who has been through issues like this. That is the only way I will get a fair treatment recommendation.”

Discussion Questions

- How might racial differences between Hunter and Selina influence their interactions and perceptions of each other’s expertise?

- What steps can be taken to address potential racial biases or cultural misunderstandings in therapeutic settings? What strategies can build culturally responsive therapeutic alliances?

- Reflecting on Hunter’s skepticism toward Selina’s expertise, how might racial stereotypes or historical mistrust impact his willingness to engage in treatment?

- Considering Selina’s role as a White counselor and Hunter’s experience as a Black client, how might cultural competence and humility contribute to effective treatment outcomes? How can counselors educate themselves about the impact of systemic racism on addiction treatment and recovery?

- Discuss the importance of cultural humility in Selina’s response to Hunter’s criticism of her expertise. How can counselors acknowledge their own limitations and biases while fostering an environment of mutual respect and collaboration?

The amount of personal space we provide between ourselves, and others varies depending on our relationship status with them (Mehta, 2020). The video linked here gives a great outline of the study of proxemics: Proxemics

Discussion Questions

- How does personal bias or your power as a human service professional impact your personal space with a client?

- How would you respond if a client is not respecting your personal space?

Equitable Distribution of Services

Triage, derived from the French verb “trier” meaning “to sort” (Christian, 2019), plays a crucial role not only in emergency room settings but also in human services agencies. Triage guides the prioritization of client services, starting during intake or initial assessments and continuing throughout the client’s service journey. Triage often follows policies established by funding sources, legislation, and human services agencies. As human services agencies are often underfunded, triage allocates limited resources efficiently and ensures timely access to care. However, concerns related to social justice arise as the triage process can inadvertently perpetuate systemic inequalities, affecting marginalized communities who may face barriers to accessing timely and appropriate services. These disparities highlight the importance of implementing equitable triage protocols prioritizing fairness, inclusivity, and respect for diverse client needs and circumstances (Christian, 2019).

The human service field also faces challenges related to wait times. From mental health visits to emergency departments, Black Americans experience the longest waiting times and are less likely to be transferred to another facility compared to White Americans (Macias-Konstantopoulos, 2023). Wait times are often influenced by over-triaging. This occurs when the human services worker identifies a high number of clients needing immediate care. When over-triaging occurs, already stretched resources are stretched even tighter, and human services agencies start to experience extended wait times for treatment, extended treatment times, errors in triaging, and overcrowding (Hitchcock et al., 2013).

An example of this is the scheduling of initial appointments. Often, there are same-day or similar appointment slots set aside for emergency intake cases. However, when clients have been over-triaged, those slots may be filled, and more urgent needs may still need to be met. A crucial step in addressing this issue is to ensure that intake specialists receive thorough training in triage protocols, encompassing a comprehensive understanding of policy regarding initial appointments, emergency cases, and triage procedures (Christian, 2019).

Access and Barriers to Resources

Human service workers assist clients in accessing essential resources. These resources can be tangible, such as housing, medicine, textbooks, transportation, or wheelchairs, or intangible, such as emotional support or education. When human service professionals strategize to provide clients with access to these resources, they must consider their circumstances and ability to utilize them effectively. Human service professionals must also consider realistic accessibility before referring clients to resources (Martin, 2018).

For example, we can tell a client, “If you go to the pharmacy, you can pick up your prescription.” However, it may not be that simple. Barriers to picking up a prescription include lack of transportation, the pharmacy’s limited hours, prescription coverage, and cost. Lee et al. (2021) identified that “non-Hispanic Whites had the highest health insurance coverage at 94.6%, followed by Asians at 93.2%, Blacks at 90.3%, and Hispanics at 82.2%” (2011, p. 1). In addition to these barriers, there may also be a language barrier or issues with health literacy that can impact medication adherence. It is a probability that all clients will experience some roadblocks in obtaining services. It is the responsibility of a human services worker to recognize these obstacles and assist clients in navigating around them.

Creating accessibility to resources requires creativity and brainstorming. Often, human services workers must think outside the box when it comes to generating access. Examples of this include contacting vendors who can provide resources at a lower cost, negotiating with community organizations to secure donated goods or services, coordinating with local transportation providers to arrange reliable travel options, leveraging social media and community networks to find support groups or educational opportunities, and partnering with businesses to create job opportunities or internships. By employing creative and resourceful strategies, human services workers can better meet the diverse needs of their clients. A bonus to identifying and managing barriers to resources is that increasing access to one resource often creates a path for future resources. For example, if we support clients in obtaining employment and stable housing, we open the door for them to access education (Martin, 2018).

Human service professionals must balance the quality of the resources against reasonability and accessibility (Martin, 2018). If the best resource is an hour’s drive away, but the client does not have access to transportation, then it is not the best resource for them. When this occurs, it is the responsibility of the human services worker to work with the client to determine what is accessible to the client. Sometimes, a lesser quality resource is better than the client not getting any resource due to lack of accessibility.

- What are some common barriers that clients from marginalized communities might face in accessing tangible resources such as housing, medicine, and transportation? How can human service professionals help clients overcome these barriers while advocating for social justice?

- Discuss the importance of understanding a client’s specific circumstances when strategizing to provide access to resources. How can human service professionals ensure they are aware of systemic inequalities that may affect their clients?

- How can human service workers balance the quality of resources against their accessibility? Consider the social justice implications of making these decisions and ensuring fair resource distribution.

- Discuss the importance of continuous assessment and adaptation in helping clients access resources. How can human service professionals ensure they remain responsive to the changing needs and circumstances of clients, particularly those from marginalized communities?

- What strategies can you employ when no accessible resources are available to clients?

Education of the Human Services Professional

Effective social justice and diversity education prepares competent practitioners (Olcon et al., 2020), and human services educators set the tone and direction for professional discourse and practice. However, theoretical frameworks and strategies for teaching social justice and diversity in education have increasingly been criticized. Sue and Sue (2016) suggest that the educational focus on cultural competence and skills such as self-awareness and personal knowledge have become the focus in higher education as opposed to anti-racist practice (Dominelli, 2008). While many human service professionals call for eliminating racism and oppression, the field has remained mostly silent on the role that Whiteness and Eurocentrism play in systemic racism and structural injustice (Olcon et al., 2020).

Human service courses in social justice that teach students about power, privilege, and oppression are essential additions to professional education. Jeyasingham (2012) explains that White human service professionals should consider engaging with “Whiteness studies” because they provide insight into the invisible and dominant ways power operates (p. 682). Social justice-focused education allows human service professionals to understand White Privilege and its potential impact on their relationships with clients. This approach to incorporating social justice education into human services must include anti-racist pedagogy (Abrams and Gibson, 2007). It is the responsibility of the human services worker to introspect and consider individual and institutional causes of inequalities that may affect their relationships with clients.

One way for human services professionals to continue their education on social justice and diversity is through obtaining licenses and credentials. Many licensing entities require professionals to complete continuing education credits, which can include specific training, classes, or conferences. By maintaining an active license or credential, human services workers remain current on the latest research and best practices in their field. Since social justice is a field that is constantly evolving, these training sessions are essential for human service professionals.

Some example credentials include (but aren’t limited to):

- Certified Case Manager

- Mental Health Counselor in New York State

- CASAC Credential in New York State

- Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC) Guide

- Licensed Clinical Social Worker in New York State

Discussion Questions

- What credential or license are you interested in obtaining, and why did you choose it?

- What are the specific educational and experiential requirements needed to qualify for this credential? How might these be easy or difficult to obtain? What social justice concerns might be present in this requirement?

- Are there any ethical considerations or professional standards associated with holding this credential? Discuss the ethical code associated with this credential.

- Are there any financial considerations associated with pursuing this credential such as application fees, exam costs, or continuing education expenses? Why might cost be an issue of social justice?

- What are the requirements for social justice or diversity continuing education for this credential? If there are none, why do you think this is so? Should there be?

Thoughts from the Authors

I have worked hands-on in the human service field for many years. I worked as a New York State Credentialed Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Counselor (CASAC) in outpatient, inpatient, long-term, and short-term facilities. My specialty was working closely with the recently incarcerated who were court-mandated to substance use treatment. While working with this population, I had to learn quite a bit about my personal biases and how to address them to be the best counselor possible. I had to check my preconceived notions about the recently incarcerated. While I have put in significant work to move toward eliminating my bias from my clinical interactions, there will never be a time when my personal bias is Poof gone. My personal bias is part of what makes me unique as a human and a counselor. As long as I keep them in the forefront of my mind so I do not let them interfere with my clinical practices, I am working towards creating a stable and safe environment for my clients.

While writing this chapter, I researched current social justice issues. At first, I read the most commonly discussed topics (e.g., George Floyd, how our prisons have a disproportionate population of minorities, etc.). However, as I dove down some internet rabbit holes, I learned about many more that have yet to be widely known or discussed. We must discuss these situations to gather the strength to make the necessary changes. Here is a short list of current social justice issues that need to be discussed and paid more attention to (please note this list is not exhaustive; instead, it is a jumping-off point to entice you to fall some of those research rabbit holes):

- How COVID-19–induced poverty has disproportionately impacted the Latino and Black communities:

- Income inequality

- Food insecurity

- Housing insecurity

- Gender-based violence

- Political extremism

- Reproductive rights

-Dr. Green

Like Dr. Green, I have worked in the human service field for many years now. I feel like I am learning a new way my biases affect my perceptions every day. How many times have you heard the older people in your lives say something like: “Kids these days…”? I find myself falling into that thinking more as I age. This is where my daughters help me to recognize how even biases based on my generation impact my interactions.

A great example is accessibility. Both of my daughters dread calling someone on the phone. They would much rather text or go online to make a reservation or send a message. When they are now at the age where they need to call to set up their own doctor’s appointments and procedures, they have shared how challenging it is and that it is something they avoid, therefore putting off getting seen by their doctors. At first, my reaction was to dismiss this and minimize the issue. Then, I stopped to think that the upcoming generation has a very different experience with communication. Just because I can easily make that phone call, are we limiting accessibility for those without that ability? I guess this is where those patient portals I still do not use come in handy. While I believe there are some beautiful traditions and lots to learn from others who have been doing things for some time, assuming that the younger generation has to do everything the way we have always done things is a potentially dangerous bias.

A few words of advice from someone who has worked in this field for many years and has learned some lessons that apply across all situations. I want to share a couple here. Your role does not matter; there are two key things to integrate into any intake in this field. First, LISTEN. There is a saying: “We have two ears and one mouth because it is twice as important to listen as it is to talk.” Actively listening means you are present, attentive, and engaged in what that person is sharing. Second, when in doubt, ask. Never assume you know someone’s experience. Even if the person looked like you and grew up in the same neighborhood as you, you have no idea what they experienced. Never be afraid to ask.

-Dr. Brayton

- Why must human service professionals be in tune with social justice and equity movements in their community?

- Why is it important that we not allow our personal biases to be shown in our work with clients? What might the consequences of this be?

- What are some examples of personal biases that have come up for you as a human services professional?

- How does connecting with culture help us recognize our biases?

- How do we decide how to distribute our time amongst our clients? What are some things we should consider?

References

Abrams, L. S., & Gibson, P. (2007). Teaching notes: Reframing multicultural education: Teaching White privilege in the social work curriculum. Journal of Social Work Education, 43(1), 147–160. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2007.200500529

American Counseling Association. (2014). Code of Ethics. ACA 2014 Code of Ethics (counseling.org)

Andreassen, R. A. (2016). Professional intervention from a service perspective. In Gubrium, J. F., Andreassen, T. A., Solvang, P., & Hamm, L. (eds), Reimagining the human service relationship (pp 33–58). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/gubr17152

Bridgwater, M. A., Petti, E., Giljen, M., Akouri-Shan, L., DeLuca, J. S., Rakhshan Rouhakhtar, P., Millar, C., Karcher, N. R., Martin, E. A., DeVylder, J., Anglin, D., Williams, R., Ellman, L. M., Mittal, V. A., & Schiffman, J. (2023). Review of factors resulting in systemic biases in the screening, assessment, and treatment of individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis in the United States. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1117022–1117022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1117022

Buggs, M. D., Catalano, C. J., & Wagner, R. (2023). Sexism, heterosexism, and trans oppression: An integrated perspective. In M. Adams (Ed.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 176–213). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003005759

Casad, B. J., & Luebering, J. E. (2023, August 18). Confirmation bias. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias

Caccavale, J. (2020, October, 12). What is contrast effect? And how it impacts recruitment. Applied. https://www.beapplied.com/post/what-is-contrast-effect-and-how-it-impacts-recruitment

Centers for Disease Control. (2023). Genderism, Sexism, and Heterosexism. Genderism, Sexism, and Heterosexism | CDC

Cherry, K. (2022, October 24). The halo effect in psychology: Attractiveness is more than looks. VeryWell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-halo-effect-2795906

Christian, M. D. (2019). Triage. Critical Care Clinics, 35(4), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2019.06.009

Crandall, A., Powell, E. A., Bradford, G. C., Magnusson, B. M., Hanson, C. L., Barnes, M. D., Novilla, M. L. B., & Bean, R. A. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a framework for understanding adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01577-4

Dominelli, L. (2008). Anti-racist social work (3rd ed). Palgrave Macmillan.

Durante, F., & Fiske, S. T. (2017). How social-class stereotypes maintain inequality. Current Opinion Psychology. 18:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.033.

Hays, D. G., & Erford, B. T. (2018). Developing multicultural counseling competence: A systems approach. 3rd edition. Pearson.

Hitchcock, M., Gillespie, B., Crilly, J., & Chaboyer, W. (2013). Triage: An investigation of the process and potential vulnerabilities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(7), 1532–1541. doi.org/10.1111/jan.12304

Hoskovec, J. M., Bennett, R. L., Carey, M. E., DaVanzo, J. E., Dougherty, M., Hahn, S. E., LeRoy, B. S., O’Neal, S., Richardson, J. G., & Wicklund, C. A. (2018). Projecting the supply and demand for certified genetic counselors: A workforce study. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 27(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0158-8

Hughes, C. (2020). Critical employment, ethical, and legal scenarios in human resource development. University of Arkansas.

Hurd, S. (2018, September 29). What is attribution bias and how it secretly distorts your thinking. Learning Mind. https://www.learning-mind.com/attribution-bias/

Jeyasingham, D. (2012). White noise: A critical evaluation of social work education’s engagement with Whiteness studies. British Journal of Social Work, 42(4), 669–686. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcr110

Kenyon, P. (1999). What would you do? An ethical case workbook for human service professionals (1st ed) Cengage.

Kowal, M., Sorokowski, P., Kulczycki, E.,& Żelaźniewicz, A. (2022). The impact of geographical bias when judging scientific studies. Scientometrics, 127(1), 265–273.

Lee, D.C., Liang, H., & Shi, L. (2021). The convergence of racial and income disparities in health insurance coverage in the United States. International Journal Equity Health, 20(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01436-z.

Macias-Konstantopoulos, W. L., Collins, K.A., Diaz, R., Duber, H.C., Edwards, C.D., Hsu, A.P., Ranney, M.L., Riviello, R.J., Wettstein, Z.S., & Sachs, C.J. (2023). Race, healthcare, and health disparities: A critical review and recommendations for advancing health equity. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(5):906-918. doi: 10.5811/westjem.58408.

Maccarone, D. (2003). The beauty bias. Psychology Today. The Beauty Bias | Psychology Today

Marsden, J., Newton, M., Windle, J., & Mackway-Jones, K. (2013). Emergency triage: telephone triage and advice. John Wiley & Sons.

Martin, M., (2018). Through the eyes of practice settings. Pearson.

McClintock, A. H., Fainstad, T., Jauregui, J., & Yarris, L.M. (2021). Countering bias in assessment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education,13(5):725-726. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00722.1.

McElroy, K., Moore, D., Hilterbrand, L., & Hindes, N. (2017). Access services are human services: Collaborating to provide textbook access to students. Journal of Access Services, 14(2), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2017.1296769

Myer, R. A., Whisenhunt, J. L., & James, R. K. (2022). Crisis intervention ethics casebook. American Counseling Association.

Office of Addiction Services and Supports. (2020). Part 822 Outpatient Services Clinical Standards. Clinical Standards (ny.gov)

Olcoń, K., Gilbert, D. J., & Pulliam, R. M. (2020). Teaching about racial and ethnic diversity in social work education: A systematic review. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656578

Reynolds, C. R., & Suzuki, L. A. (2012). Bias in psychological assessment. Assessment Psychology. In Weiner, I. B (Eds.), Handbook of Psychology. (82–113). John Wiley & sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop210004

Ricee, S. (2023, July 13). What is affinity bias? Diversity for Social Impact. https://diversity.social/affinity-bias-definition/

Ross, H. J. (2020). Everyday bias: Identifying and navigating unconscious judgements in our daily lives. Rowman & Littlefield.

Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4

Silvestre, C. C., Santos, L. M. C., de Oliveira-Filho, A. D., & de Lyra, D. P. (2017). ‘What is not written does not exist’: The importance of proper documentation of medication use history. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 39(5), 985–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0519-2

Stiffler, M. C., & Dever, B. V. (2015). Mental Health Screening at School Instrumentation, Implementation, and Critical Issues (1st ed. ). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19171-3

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Crisis intervention team (CIT) methods for using data to inform practice: A step-by-step guide. HHS Pub. No. SMA-18-5065.

Sue, D. W., & Sue, D. (2016). Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (7th ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Sue, D. W., Rasheed, M. N, & Rasheed, J. M. (2016). Multicultural social work practice (2nd ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Summers, J. (2019). Theory of healthcare ethics. In E.E. Morrison & B. Furlong (Eds.), Health Care Ethics: Critical Issues for the 21st Century (4th ed., pp. 3–39). Jones & Bartlett.

Veesart, A., & Barron, A. (2020). Unconscious bias: Is it impacting your nursing care? Nursing Made Incredibly Easy!, 18(2), 47–49. doi: 10.1097/01.NME.0000653208.69994.12.

Walker, P. (2020). Triage in a pandemic; equity, utility, or both? Ethics & Medicine, 36(3), 147–131.

Media Attributions

- Bronfenbrenners Ecological Theory of Development © Abbeyelder is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

About the authors

name: Cailyn F. Green

Cailyn F. Green is a Certified Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Counselor- Masters Level (CASAC-M) through New York State. She is the Addiction Studies Professor at the State University of New York: Empire State University. She earned her BA from Western New England University in Springfield, MA and her MS in Forensic Mental Health from Sage Graduate School in Albany, NY. Her Ph.D is in Criminal Justice, specializing in Substance Use from Walden University in Minneapolis, MN. Dr. Green has over 10 years of experience teaching both in online and in-person college-level settings in substance use, human service, criminal justice and clinical counseling topics. She won the Scholars Across the University award in 2024 for her research in substance use topics and this social justice-focused textbook. She has 9 journal article publications to date and her other published textbooks include Evidence-Based Substance Use Treatment and the Group Counseling Workbook.

name: Kim Brayton

Dr. Brayton received a joint law and clinical psychology doctorate in California at Palo Alto University and Golden Gate School of Law. She is a professor at Russell Sage College where she heads the program working with students in forensic mental health. Additionally, she has a private practice where she specializes in treating adult survivors of trauma and forensic assessment. In her spare time she enjoys golf, reading and the various exotic locations she bikes through on her stationary bike.

name: Carrie Steinman

Carrie Steinman, Ph.D., LMSW, MS, has been a faculty member in the School of Human Services at SUNY Empire State University since 2016. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Welfare from Stony Brook University, an LMSW from Hunter College School of Social Work, and a Master of Science in Counseling and Development from Long Island University. With a Ph.D. in Social Welfare and as a New York State Licensed Social Worker (LMSW), Dr. Steinman brings extensive practical experience to her academic role. She has worked with a range of vulnerable populations, with expertise in child welfare, including foster care, juvenile offenders, and homeless and at-risk youth. Her professional background includes work as both a clinician and an administrator across various agency settings. At SUNY Empire, Dr. Steinman has contributed to curriculum development and revision as a member of the School of Human Services Curriculum Committee. She currently serves as co-chair of the school’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice (DEISJ) Committee, which she joined at its inception in 2020. In this role, she has helped integrate anti-racist practices and DEISJ principles into the curriculum.

name: Bernadet DeJonge

Bernadet (Bernie) DeJonge, PhD, CRC, LMHC, has her BA in psychology (1999) and MA in Rehabilitation Counseling (2007) from Western Washington University. Her PhD is from Oregon State University in Counseling (2022). She is currently an Assistant Professor in the School of Human Services at Empire State University. Bernie’s areas of interest include DEIB, the integration of counseling into medical services, online pedagogy, and disability.