15 Social Justice Practice in Human Services: A Systems Approach

Cailyn F. Green; Kim Brayton; Carrie Steinman; and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will understand the history and current issues regarding systematic barriers to clients receiving human services.

- The reader will analyze the systems behind addressing housing emergencies, disaster planning, and intimate partner violence in an equitable way.

- The reader will describe how historical human service theories guide professionals working in the field today.

Introduction

A system is a combination of resources, people, institutions, and processes working towards a similar goal (Clarkson et al., 2018). Systems are created to help people and entities complete work more efficiently. Human service professionals often work within systems regarding intake processes, documentation, billing, and other logistics. Human service professionals should recognize that the environment and culture of a social service organization/system may be an inherent obstacle to clients’ successes. Additionally, workers must recognize that the problems clients face when accessing services are due to organizational or systemic issues. Multicultural organizational development is an approach to ending organizational oppression and discrimination (Sue et al., 2016). This chapter will examine the intersection of human services systems and social justice.

Power Structures

Human service organizations depend on the rules and regulations set by different stakeholders to succeed. This is a common practice of all service agencies, governmental or non-profit. Human service professionals often become accustomed to following these rules and may forget the power their role gives them. When the human service professionals assess the level of care the client needs, formulate the treatment plan, and interact with the insurance companies, the client can feel as if they have no control over the outcome (Andreassen, 2016). Human service professionals should always remember that their clients are human and may be in vulnerable situations (Nesoff, 2022). While this power dynamic between the worker and client may be challenging, a client-centered, collaborative approach to working together is crucial to demonstrating respect (Spencer et al., 2019).

Power Roles

Human service professionals must recognize that the environment and culture of a social service organization may be an inherent obstacle to client success. The human services worker/client relationship is power-centric, and clients may perceive that human services professionals have the power to provide them with access to resources and services. However, it is often the agency itself that has the most power in human service organizations.

Many social service organizations support monocultural policies and practices in their agencies where only one way of doing things is supported and enforced. An example of a monoculture would be a substance use treatment facility choosing not to practice harm reduction techniques even though harm reduction is identified as an evidence-based best practice. The agency, and subsequently the human services workers, see this as “we just don’t do it that way here.” Monocultural attitudes often result in outdated methods being used at an agency, as change is rejected in favor of the status quo (Sue et al., 2016).

Progressing from a monocultural to a multicultural organization requires agencies to understand both mono- and multicultural strategies and analyze whether the agency’s policies and procedures promote an organizational culture of access and equity. Multicultural Organizational Development (MOD) is a theory that examines organizations through a social justice framework. MOD is an approach to ending organizational oppression and discrimination, and can be used to analyze and change monocultural attitudes at the organizational level. MOD investigates the power imbalance between management and employees and how that relationship impacts clients of human services (Sue et al., 2016).

Human service workers must recognize that issues with client access to services are often due to organizational or systemic issues. According to Sue et al. (2016), monocultural organizations have policies and procedures that may impede a worker’s attempt to provide their diverse clients with “culturally appropriate services” (p. 345). For an agency, and, consequently, a worker, to provide culturally competent services, the organization must have workers who practice cultural competence, and the organization itself must have a culture of competence and proficiency around DEI issues (Sue et al., 2016).

- If you have experience in a human service organization as a client or a worker, would you rate that agency as monocultural or multicultural? How do you decide if an agency is monocultural or multicultural?

- What social justice issues might emerge from policies or practices at human services agencies?

- What interventions can be used by organizations to meet the needs of diverse clients?

- What are the supports and barriers to implementing anti-oppressive practices in human services organizations? How do we overcome these barriers?

Systemic Barriers to Service

When a human service provider is tasked with identifying a client’s needs, the first step is to undertake a comprehensive needs assessment. This needs assessment provides information to help connect clients with the resources that address their needs. While each client has different needs, there are some common systemic barriers to receiving services. Examples include access to identification or documentation, internet access, and language barriers.

Many marginalized populations do not have access to identification. Research shows that 21% of Black Americans, 23% of Latin Americans and 68% of Transgender Americans do not have a valid form of identification (Hesano, 2023). Lack of identification creates an immediate social justice issue as many government and privately funded resources require identification for clients to receive benefits. Some government organizations have acknowledged the systemic racism and inequities in their policies and are working to improve access and remove obstacles for clients, yet many have not. It is the task of the worker and the client together to identify and resolve potential issues before the client is sent to receive services.

Internet access is another systemic issue of equity when considering human service clients. Access to services usually starts online where applications, program requirements, costs, and intake forms are found. While this is convenient for the agency and individuals with reliable internet access, many clients lack stable, reliable internet access. Before assuming that a client has stable internet, the human services worker should assess this as a potential barrier (Bauerly et al., 2019). If a client does not have access to the internet, it is the responsibility of the human service worker to problem-solve this with the client. This may look like helping them find a local library or community program that offers internet access, or, if your role permits, assisting them to access the internet. Human service workers must also be aware that some clients may struggle not only with internet access but also lack the computer skills to utilize it, even when access is provided.

If a client experiences a language barrier, it is important for the human service provider to acknowledge this and find ways to assist the client. Supporting monolingual habits, where an agency only provides resources in one language or does not offer language interpretation support, leads to social exclusion. This becomes a social justice issue when a client cannot communicate effectively with their treatment provider (Papa, 2020). Many human service professional agencies contract with interpreters, which can be accessed via phones. This looks like a client being in a session with the human service provider, calling the interpreter and putting them on speaker. They support the professional in communicating with the client.

Dr. DeJonge (Bernie) here. I have worked extensively with interpreters in a variety of settings and have had my share of good, bad, and everything in between. Here are some real-world examples from my work.

I had a client from Iraq who had a crippling depression and would only sit on the floor in a corner. The Farsi interpreter, who was a woman, explained the cultural significance of this, walked me through appropriate vs. inappropriate questions on my assessment to ask in front of the men present, and cued me for cultural considerations like taking off my shoes. Because of her contextual information, I was able to build a solid rapport with the client and her family support system.

I had a Muslim caregiver from the Middle East who needed an interpreter to complete her paperwork and training. The interpreting agency sent a male interpreter. She got very upset and refused to meet with him, particularly since I wanted to leave them alone to watch a required video. The male interpreter explained to me it was not socially appropriate for him to be alone with her. The next visit, I ensured the agency sent a female interpreter.

I had a Spanish interpreter who was interpreting for an Adult Protective Services case I was investigating. I would ask questions, and he would give short one-to-two-word interpretations to the client. I speak a little bit of Spanish, so I was able to follow along and knew he was not providing good interpretation services. The family member who was present also said he was being rude with the client. I terminated the session and completed my interview via phone with a different interpreter later.

I did assessment work in a large Russian/Ukrainian population area. It was a rural area, and there was only one certified interpreter in the entire county. She and I saw countless families together. She taught me many cultural expectations (such as never turning down food) and helped me to learn how to do my assessments in a culturally competent fashion. In addition, I had strong trust in her and she often could tell me when things did not seem right or if there were issues I was not capturing in my assessment. I learned how effective good interpreters can be through that experience.

Video: Best Practice in Using Interpreters

Video: Working with Interpreters in the Healthcare Setting

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important for interpreters to provide cultural context in addition to linguistic translation?

- How can professionals assess the quality of interpretation services during a session?

- Why is building trust between interpreters and social service professionals crucial for effective service delivery?

- What strategies can be employed to handle interpreter shortages in rural or underserved areas?

- What are the ethical considerations involved in using interpreters?

Safety Net Services

Safety net services refer to government or community programs designed to provide a minimum level of support to individuals and families facing financial hardship or other vulnerabilities. Generally, safety net services are government-funded. Safety net services aim to ensure that basic needs are met, particularly for those who are unemployed, underemployed, or otherwise unable to support themselves. Examples of safety net services include Electronic Benefits Cards (EBT, previously known as food stamps), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), housing benefits, Medicaid, Medicare, childcare, and transportation assistance.

Accessing safety net services is often frustrating for human services clients. Often, there is a lengthy paperwork process to gain access to one or more of these services. Researching eligibility requirements, required documentation, language barriers, hours of operation, walk-ins or appointments only, and contacting someone at the location before referring clients to the agency is essential. These steps can help clients avoid frustration and save time and money. In addition, many social services offices that provide safety net services struggle with staffing and resource management. Thus, wait times both in person and on the phone can be significant. For example, it is not uncommon to wait on hold for over an hour when trying to call the Social Security Office. Although frustrating, this is sometimes preferable to going in person to an office where the wait might be longer.

Often, these offices do not allow for drop-in appointments, and clients should be warned if they need an appointment ahead of time to speak to someone. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, many programs now require reservations or appointment times to meet with agency workers. Once contact is made, intake and paperwork can be overwhelming. Intake forms are a way to collect a client’s contact information and presenting issues or needs. Most questions on this form will focus on gathering eligibility information, and a file will be started. Information gathered may include medical history, social support, mental health background, and financial status. The intake form will typically ask questions to identify if the client is experiencing dangerous living situations or needs immediate food support. This intake form will also inquire if the client is experiencing any self-harming or suicidal behaviors and thoughts.

Suppose the client does not have any medical or mental health, dangerous living situations, or lack of food emergencies. In that case, they will most likely be given an appointment time and date to come back and formally meet with a case manager who is best suited to address their expressed areas of concern. Suppose the client expresses concerns regarding safety in their living situations, food availability, or self-harming or suicidal thoughts. In that case, they will be transferred to a case manager that day to address these areas of concern. No client should ever be left alone to deal with a life-threatening or unsafe situation.

Video: Human Services Traffic Jam by Erine Gray

Discussion Questions

- How do you find resources in your community? Is the website or phone number easy to access? Why or why not?

- What are some ways you can help your clients troubleshoot and avoid potential challenges when accessing these resources?

- What are some ways human service and community resource agencies can save money?

Housing Emergencies

The issue of homelessness and housing insecurity has always been a severe problem in the United States. Housing insecurity, from affordability to homelessness, is a problem that increased after the COVID-19 pandemic. When Americans are having difficulty accessing affordable, safe housing, this escalates the need for emergency shelters and other emergency housing services (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2019). These emergency shelters and other emergency resources are funded and distributed by state and local government entities.

People of color are almost twice as likely as White individuals to experience housing insecurity (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2019). Structural racism has been a longstanding problem in the United States housing system and is only more evident today. Pre-pandemic rates consistently showed that more than half of the homeless population was typically found in major cities in the United States. According to the State of Homelessness in America report put out in 2023 by the National Alliance to End Homeless, there are an estimated 421,392 people (about half the population of Maine) experiencing homelessness on any given night; the majority (65%) stay in sheltered venues (including emergency shelters), with 35% in unsheltered locations (on the streets or in encampments). Six percent are veterans, and 22% are chronically homeless individuals. This report identifies that the majority of our homeless population are native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Black or Brown people.

Recently, in New York City and other cities, the immigration crisis has made the shortage of shelter beds and housing for people with low incomes even more acute. In 2023, New York City opened 186 emergency shelters to cope with the large influx of homeless migrants (Hogan et al., 2023), but it was not without controversy.

Large amounts of money and resources go towards systems to house the large influx of migrant individuals, which has been met with controversy. One side argues that the individuals who live in New York City need those resources, and the other advocates for aiding the migrant individuals. According to the Coalition for the Homeless (2024), in March 2024 there were an estimated 350,000 homeless individuals living in New York City. Further controversy stems from whether New York City supports its own homeless population before spending money on an additional homeless population being brought in.

Discussion Questions

- How should New York City prioritize its resources between existing homeless residents and the incoming migrant population?

- What factors should be considered when allocating shelter beds and housing resources?

- What ethical dilemmas arise from allocating resources to migrants versus existing homeless individuals?

- What long-term solutions can be proposed to handle both the existing homelessness crisis and the needs of new migrants?

- What best practices from other cities can New York City adopt to improve its response to homelessness and migrant influxes?

Working with clients with housing insecurity or homelessness is a very challenging intervention. Contacting county or city Emergency Housing Services is the entry point in locating and securing emergency and long-term housing. Human service professionals advocating for their clients should know the eligibility and documentation required to apply before sending them directly for assistance. Safe housing is a highly scarce resource, and some of the options provided to clients are so unsafe that they choose to be homeless instead of staying in shelters. Human service professionals must convey empathy and understanding if a client chooses this.

Video: So you think you understand homelessness by Marisa A. Zapata

Discussion Questions

- What has changed with the homelessness issue?

- What is happening in the community you live in regarding homelessness?

- How are communities addressing homelessness? Is it working?

- How does your community address homelessness?

- How does homelessness impact your community?

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a complex scenario in human service systems. IPV is complicated as the human services worker must work within their system to balance safety, human rights, personal decision-making, and their potential personal bias. The first ethical responsibility of the human services worker is to offer safety and resources to our clients when they disclose IPV (Warshaw, 2019). That said, clients will not always accept this support for a variety of reasons. It is also the ethical responsibility of the human service worker to respect a client’s choice. Clients have the basic human right to make their own choices, including staying in an IPV situation. This may look like a person going back to an IPV living situation against their case manager’s advice. Managing a case with IPV involved is a difficult situation for any human service professional. The human service professional must keep their personal bias and feelings out of the interaction and focus only on offering resources and respecting the client’s decisions (Warshaw, 2019).

Video: What’s Love Gotta Do With It? from the OMH Resource Center

Discussion Questions

- What factors contribute to the prevalence of IPV on college campuses?

- What strategies can be used to change campus culture regarding IPV?

- How does IPV impact a student’s academic performance and mental health?

- What innovative approaches could be developed to combat IPV on college campuses?

- How can research on IPV in college settings inform broader societal efforts to address the issue?

Disaster Planning and Response

The World Health Organization’s disaster model includes vulnerability, hazards, and trigger events, including storms, earthquakes, floods, and fires (Morrison & Bawel-Brinkley, 2019). When different individuals, communities, or cultures go through a devastating disaster, their needs can be drastically different depending on the community’s trauma. Part of applying human rights as human service professionals is ensuring all people involved in the disaster are offered the support they need, prioritizing physiological and safety needs, following Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Crandall et al., 2020). For example, if a tornado hits a community in Kansas, the first responders will be there as soon as possible to offer universal support like first aid, food, and clothing. What if Family A does not need first aid or food? They may need housing as they have a sick child who should not be out in the cold weather. Family B may need more food, but no shelter as they have friends they can go to stay with. Applying human rights to this situation will involve the human service professionals identifying what resources each unique family needs and doing their best to provide them. It is much easier to think “we just offer everyone the same things,” but that is not what being a human service advocate looks like. We must advocate for our clients to receive the resources they each need.

Human service professionals walk a very thin line in our work, and it is their responsibility to utilize evidence-based best practices to make daily decisions. The professionals job is first to identify resources uniquely needed by each client. It is then their responsibility to help support clients in obtaining these resources. However, they must keep their personal bias out of the conversation and respect our clients’ decisions in these life-changing events.

Video: How to organise social services during and after a natural disaster?

Video: 4 nursing home residents die after Ida evacuation

Discussion Questions

- How can human service organizations ensure they are adequately prepared for different types of disasters?

- How can agencies ensure that vulnerable populations receive timely and appropriate emergency services?

- How can human service agencies support individuals and communities in rebuilding their lives post-disaster?

- What ethical dilemmas might arise during disaster interventions, and how can they be addressed?

- Discuss what went wrong in the nursing home video. How would you have done things differently for these vulnerable residents? What kind of advocacy work still needs to be done around disaster and vulnerable populations?

How Theories Impact Human Service Practices

It is important to create ethical and equitable resources for human service clients. Often, this is framed through a human rights lens. Below are a few theories as to how human rights are interwoven into human services, including (a) authority-based theories, (b) natural law-based theory, (c) teleological theories, and (d) virtue ethics theory.

Authority-based theories in human service typically refer to theories that emphasize the role of authority figures, structures, or systems. Authority-based theory posits that the right thing to do is based on what an authority figure has decided (Summers, 2019). Authority-based theories can be faith-based, as, historically, religions and faiths have told us what is right versus wrong. An example of authority-based theory impacting human services is the decision-making chain of command. When a clinical supervisor tells the human service professional what to do, they expect follow-through. In this case, the authority figure is the clinical supervisor, and they are deciding on what is ethically right or wrong.

Authority-based theories underlie many ethical codes in human services. This can be a challenge, as ethics, by definition, often involves difficult grey areas. In addition, many human service workers and organizations have a governing body that provides direction in treatment that can be seen as authority-based. Organizations develop policies and procedures, or written rules, that their employees must follow, and they are expected to do so without question.

Natural law-based theory is a philosophical and ethical perspective that asserts that universal principles govern human behavior and morality. These principles are believed to originate from nature or a higher order of reality rather than from human-made laws or social conventions (Summers, 2019). The governing religion or political beliefs often influence the perception of natural laws. This may be demonstrated in human services when agencies have a political or religious agenda. This agenda may impact the ability of human services workers to serve clients ethically. One example of a natural law is that people are not allowed to kill each other. We saw this being enforced differently while going through the COVID-19 pandemic. The life threatening nature of the illness provoked governments, agencies, and communities to adopt practices like mask-wearing and social distancing due to how this natural pandemic spread, and the damage it caused.

Teleological theories, often referred to in philosophy, focus on the consequences of decisions (Summers, 2019). These theories aim to maximize the potential good outcomes from a given situation. Theories about what is right and wrong are standardly divided into two kinds: those that are teleological and those that are not. Teleological theories first identify what is good in states of affairs and then characterize right acts entirely in terms of that good. (Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2019, para 1). This may look like a human service professional deciding on a treatment plan based on the best outcomes for a client’s living, family, work, and financial situations.

Virtue ethics theory stems from Plato and Aristotle. Virtue theory posits that all people are virtuous at their core (Summers, 2019). Virtue ethics suggests that everyone wants to follow the best possible ethical standards. In human services, this can look like a human service professional thinking about how a client’s life can benefit and become better with their involvement. This is the very basis of the Hippocratic Oath—“above all, do not harm.” This overarching belief relates to the thought that the intentions of those working in the human service sectors are all based on wanting to help others and the commitment that what we do will not hurt another.

Strategies for Systemic Change

Promoting systemic change in favor of our social justice climate will not come easy. These changes will require work that will need to start from the bottom and rise up through the systems, this is challenging work. Some ways people can make systemic change is by leading with evidence based policy (Mears, 2022). This happens when individuals educate their system officials with acts and policies that have been proven to create direct positive impact on the community (Mears, 2022).

Interventions are also a way to promote systemic change in a positive way. When human service works implement interventions to better support social justice causes, they are integrating systemic changes (Mears, 2022). As these interventions show themselves to be helpful, they should become ingrained in the system and promote long term change.

Dr. Courtney Harris, M. Ed is an experienced language arts educator located in Texas. She has spent her professional career focused on fostering positive learning environments for students from diverse backgrounds. She has created a workbook for people to use to help learn how they can advocate for social justice in their own communities. This workbook focuses on 20 specific ways one can impact social justice issues from a systemic approach. These vary from supporting products and services that align with your positive social justice mindset to writing letters or calling local politicians to seek reform.

Article: 20 Ways to Be An Advocate for Social Change and Transformation

Discussion Questions

- Which one of Dr. Harris’ ways to be a systemic advocate for social change have you practiced? Please explain.

- Which one of Dr. Harris’ ways to be a systemic advocate for social change do you think you could incorporate into your daily routine? Please explain.

- Which one of Dr. Harris’ ways to be a systemic advocate for social change can you engage in to make a large systemic change? Please explain.

- How can you encourage others to engage in the practices to create more advocates for systemic social change?

Thoughts from the Authors

I had to do a significant quantity of background research before I could even think about starting to write this chapter. This chapter included many topics that I thought I was knowledgeable about… However, I found that I was not as savvy as I thought. I always placed the “human rights” concept in international affairs or public policy. Learning about human rights’ role in everyday interactions with clients was eye-opening. Writing this chapter reminds me of how I am always learning, expanding my knowledge base, and growing to become a more robust human service professional.

-Dr. Green

As for me, one thing that has enhanced my appreciation for our role in respecting human rights is my advanced studies in trauma. In this field, there is a practice called Trauma-Informed Care. The premise of this practice is that we approach people in a way that considers that we may not know what potentially traumatizing experiences have happened to them. Because others have hurt many people, I want their interactions with me to be safe, consistent, and predictable. This is why I am on time for appointments. I stop listening to what someone is saying, and I try to empower others by allowing them to choose what steps they want to pursue. Remember, though you may be a professional, you are still human and will never be perfect, so it is also important to acknowledge when we make mistakes. Something as small as saying “I am sorry” goes a long way to show how much we respect that other person. Not only does it create a safe experience for someone with a trauma history, but it is also the ultimate way to respect human dignity.

-Dr. Brayton

- In your own words, explain the role the government plays in allocating resources to human service clients and the role social justice can play in this action.

- What are some examples of screenings that can be used for substance use? Suicide? Mental Health? How can screening be adjusted to support social justice concepts?

- Why must human service workers utilize evidence-based best practices when deciding how to deal with specific situations?

- How can the natural power struggle between a human service worker and client hinder the treatment process?

References

Andreassen, R. A. (2016). Professional intervention from a service perspective. In Gubrium, J. F., Andreassen, T. A., Solvang, P., & Hamm, L. (eds), Reimagining the human service relationship (pp 33-58). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/gubr17152

Bauerly, B. C., McCord, R. F., Hulkower, R., & Pepin, D. (2019). Broadband access as a public health issue: The role of law in expanding broadband access and connecting underserved communities for better health outcomes. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(2_suppl), 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110519857314

Christian, D. M. (2019). Triage. Critical Care Clinics, 35(4), 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2019.06.009

Clarkson, J., Dean, J., Ward, J., Komashie, A., & Bashford, T. (2018). A systems approach to healthcare: From thinking to practice. Future Healthcare Journal. 5(3), 151-155. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.5-3-151.

The Coalition for the Homeless. (2024). Basic facts about homelessness: New York City. https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/basic-facts-about-homelessness-new-york-city/

Crandall, A., Powell, E. A., Bradford, G. C., Magnusson, B. M., Hanson, C. L., Barnes, M. D., Novilla, M. L. B., & Bean, R. A. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a framework for understanding adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01577-4

Hesano, D. (2023, November 16). How ID requirements harm marginalized communities and their right to vote. Democracy Docket. https://www.democracydocket.com/analysis/how-id-requirements-harm-marginalized-communities-and-their-right-to-vote

Hogan, B., Crane, E., & Hicks, N. (2023, July 11). Major Adams warns that NYC is still ‘dealing with a silent crisis’ as two new mega migrant shelters open. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2023/07/11/adams-opens-two-new-emergency-relief-centers-as-migrants-surpass-54k/

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2019) . The state of the nation’s housing: 2019. Harvard Graduate School of Design and Harvard Kennedy School.

King, N. B. (2019). Health inequalities and health inequities. In E.E. Morrison & B. Furlong (Eds.), Health care ethics: Critical issues for the 21st century (4th ed., pp. 197-209). Jones & Bartlett.

McClintock, A. H., Fainstad, T., Jauregui, J., & Yarris, L.M. (2021). Countering bias in assessment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education.13(5), 725-726. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00722.1.

Mears, D. P. (2022). Escaping the sisyphean trap: Systemic criminal justice system reform. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 47(6), 1030–1049. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-022-09711-7

Morrison, E. E., & Bawel-Brinkley, K. J. (2019). Ethics of disasters: Planning and response. In E.E. Morrison & B. Furlong (Eds.), Health care ethics: Critical issues for the 21st century (4th ed., pp. 221-239). Jones & Bartlett.

National Alliance to End Homeless. (2023). 2023 state of homelessness. https://endhomelessness.org/state-of-homelessness/

Nesoff, I. (2022). Human service program planning through a social justice lens. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003148777

Papa. R. (Eds.). (2020). Handbook on promoting social justice in education. Springer Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14625-2_111

Spencer, J., Goode, J., Penix, E. A., Trusty, W., & Swift, J. K. (2019). Developing a collaborative relationship with clients during the initial sessions of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 56(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000208

Sue, D. W., Rasheed, M. N, & Rasheed, J. M. (2016). Multicultural social work practice (2nd ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Summers, N. (2016). Fundamentals of case management practice: Skills for the human services (5th ed.). Cengage.

Walker, P. (2020). Triage in a pandemic; equity, utility, or both? Ethics & Medicine, 36(3), 147–131.

Warshaw, C. (2019). Domestic violence: Changing theory, changing practice. In E.E. Morrison & B. Furlong (Eds.), Health care ethics: Critical issues for the 21st century (4th ed., pp. 237-258 ). Jones & Bartlett.

World Health Organization & United Nations. High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2008). Human rights, health, and poverty reduction strategies. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43962

Media Attributions

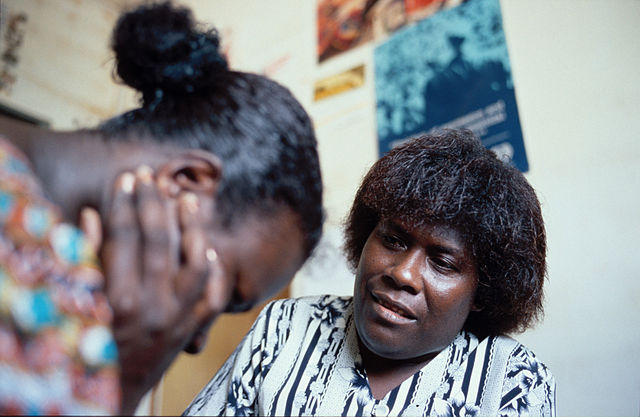

- PNG counselling service for women © Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

About the authors

name: Cailyn F. Green

Cailyn F. Green is a Certified Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Counselor- Masters Level (CASAC-M) through New York State. She is the Addiction Studies Professor at the State University of New York: Empire State University. She earned her BA from Western New England University in Springfield, MA and her MS in Forensic Mental Health from Sage Graduate School in Albany, NY. Her Ph.D is in Criminal Justice, specializing in Substance Use from Walden University in Minneapolis, MN. Dr. Green has over 10 years of experience teaching both in online and in-person college-level settings in substance use, human service, criminal justice and clinical counseling topics. She won the Scholars Across the University award in 2024 for her research in substance use topics and this social justice-focused textbook. She has 9 journal article publications to date and her other published textbooks include Evidence-Based Substance Use Treatment and the Group Counseling Workbook.

name: Kim Brayton

Dr. Brayton received a joint law and clinical psychology doctorate in California at Palo Alto University and Golden Gate School of Law. She is a professor at Russell Sage College where she heads the program working with students in forensic mental health. Additionally, she has a private practice where she specializes in treating adult survivors of trauma and forensic assessment. In her spare time she enjoys golf, reading and the various exotic locations she bikes through on her stationary bike.

name: Carrie Steinman

Carrie Steinman, Ph.D., LMSW, MS, has been a faculty member in the School of Human Services at SUNY Empire State University since 2016. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Welfare from Stony Brook University, an LMSW from Hunter College School of Social Work, and a Master of Science in Counseling and Development from Long Island University. With a Ph.D. in Social Welfare and as a New York State Licensed Social Worker (LMSW), Dr. Steinman brings extensive practical experience to her academic role. She has worked with a range of vulnerable populations, with expertise in child welfare, including foster care, juvenile offenders, and homeless and at-risk youth. Her professional background includes work as both a clinician and an administrator across various agency settings. At SUNY Empire, Dr. Steinman has contributed to curriculum development and revision as a member of the School of Human Services Curriculum Committee. She currently serves as co-chair of the school’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice (DEISJ) Committee, which she joined at its inception in 2020. In this role, she has helped integrate anti-racist practices and DEISJ principles into the curriculum.

name: Bernadet DeJonge

Bernadet (Bernie) DeJonge, PhD, CRC, LMHC, has her BA in psychology (1999) and MA in Rehabilitation Counseling (2007) from Western Washington University. Her PhD is from Oregon State University in Counseling (2022). She is currently an Assistant Professor in the School of Human Services at Empire State University. Bernie’s areas of interest include DEIB, the integration of counseling into medical services, online pedagogy, and disability.