11 Religion in the United States

Bernadet DeJonge; Nikki Golden; and Cailyn F. Green

- The reader will investigate the history of religion in the United States.

- The reader will connect the history of religion in the United States to current social justice concepts.

- The reader will identify current issues in antisemitism and Muslim hate in the United States.

The experience of religion in the United States is varied and complex. It is generally taught in school that the United States of America was founded by individuals fleeing religious persecution (Butler et al., 2007). People in the United States proudly declare that religious freedom is a foundation of this country. However, freedom of religion was not always as “free” as the story is told. This chapter will start with a discussion of United States law and religion, provide a brief historical context on religion in the United States, and discuss the current status of two religions facing significant discrimination in the United States today, Judaism and Islam.

United States Law and Religion

The phrase “separation of church and state” was coined by Thomas Jefferson in 1802 (Ryman & Elkhorn, 2009). The First Amendment of the United States Constitution states that

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. (Congress.gov, n.d., para. 1. n.d.)

The United States Supreme Court is responsible for upholding the constitution, and thus protecting the first amendment. However, the First Amendment has been interpreted in different ways by different iterations of the Supreme Court. Thus, separation of church and state in the United States has historically had a rocky, complicated, and inconsistent implementation (Sarat, 2012).

Sarat (2012), a scholar who studies the intersection of law and religion, discusses two different Supreme Court cases regarding religious freedom to point out how the implementation of the law is not always consistent.

The first case, Reynolds v. United States (1879), involved a Mormon man, George Reynolds, who was convicted of bigamy under federal law. The court did not side with the defendant, who was practicing polygamy. The Supreme Court justice who wrote the deciding opinion stated that the defendant was free to believe whatever he wanted, however, he was not free to act on this in a way that violated the law. This case established the belief-action distinction in First Amendment jurisprudence.

The second case, Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) involved members of the Amish community who refused to send their children to public high school, citing their religious beliefs. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled on the side of the Amish community who did not want to adhere to compulsory education laws. The deciding opinion argued that because the Amish were generally law-abiding and had a religious justification for not wanting their children to go to high school, they were allowed an exemption to the law. In this decision, the state’s interest in compulsory education did not outweigh the Amish families’ First Amendment right to free exercise of religion.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think Sarat (2012) chose to highlight Reynolds v. United States (1879) and Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972)?

- Are these cases the same? What are the similarities? What are the differences?

- How do we explain the inconsistencies between these two cases?

- Is the First Amendment open to interpretation? How?

The ramifications of the legal rulings regarding the First Amendment are significant. However, there are other laws that also impact religious freedoms. Some of the most important laws protecting religious freedom in the United States are labor laws.

In the United States, it is illegal to discriminate based on religion in the workplace. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Council (EEOC, n.d.) defines religious discrimination as

treating a person (an applicant or employee) unfavorably because of his or her religious beliefs. The law protects not only people who belong to traditional, organized religions, such as Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, or Judaism, but also others who have sincerely held religious, ethical or moral beliefs. (p. 1)

The EEOC goes on to clarify that it is illegal to discriminate, harass, or segregate based on someone’s religious beliefs and that there is a legal obligation to provide reasonable accommodation for religious practices.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act is also used, at times, to protect religious freedom. The Civil Rights Act covers any entity or program which receives any federal funding (US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Although Title VI does not protect specifically against religious discrimination, it does protect against discrimination based on ancestry, ethnic characteristics, or citizenship from a country with a dominant religion (US Department of Education, n.d.).

Video: Muslim Woman Sues Company After Facing Religious Discrimination

Discussion Questions

- Do you think the woman in the video was discriminated against? Why or why not?

- What did the employer do that was discriminatory?

- If you were a judge, how would you rule on this lawsuit?

- Which of the laws above apply here? Discuss.

Historical Aspect of Religion in the United States

Colonialism and Christianity are intertwined throughout the complex history of the United States. Understanding how religion is experienced in the United States today starts by understanding the history of how the United States was founded and how different political, religious, and cultural forces shaped United States history.

Early Religion in the United States

White settlers brought multiple branches of Christianity to the United States. In the original English colonies, those who did not belong to accepted Christian religions had less rights than those who did. In addition, non-Christian religions were often scorned and those who practiced them, such as Indigenous people, were persecuted, ostracized, converted, and killed. Davis (2010) described:

In newly independent America, there was a crazy quilt of state laws regarding religion. In Massachusetts, only Christians were allowed to hold public office, and Catholics were allowed to do so only after renouncing papal authority. In 1777, New York State’s constitution banned Catholics from public office (and would do so until 1806). In Maryland, Catholics had full civil rights, but Jews did not. Delaware required an oath affirming belief in the Trinity. Several states, including Massachusetts and South Carolina, had official, state-supported churches. (para. 10)

A Brief History of English Colonization in the United States

The Catholic Church had pervasive political and social influence throughout the Middle Ages. However, in the early 16th century, dissidents in England rose up, and brought new ideas to Christianity. As the Protestant Reformation took hold in England, conflict developed between the English monarchy and the Catholic Church as well as some smaller branches of Christianity. Many chose to leave England due to the religious uprising. Some went to other parts of Europe. Others came to America.

The Protestant Reformation is a significant piece of the United States’s origin. America was considered a place where people could freely practice different faiths. Many people migrated from England in hopes that they could establish religious communities without interference from the Catholic Church, the English monarchy, or the Church of England. Those who emigrated across the Atlantic included Puritans, Quakers, Baptists, Shakers, and Jewish people (Gjelten, 2017).

A Brief History of Spanish Colonization in the United States

As the Spanish inquisition took hold in 1492, Queen Isabella of Spain ordered all Jews and Muslims to leave Spain or convert to Christianity. Many fled to America. This immigration expanded with the sailing of Christopher Columbus to the Americas and the Spanish began to occupy much of what are now the southern United States, Central America, and South America. Missionaries saw Indigenous peoples as opportunities to spread Christianity, and “Between 1500 and 1800, as many as 15,000 European priests arrived in the Americas” (Butler et al., 2007, p. 24).

The Spanish explorers and colonists did not allow Indigenous people to openly practice their own religion, and Spanish authorities destroyed whatever Indigenous religious objects they could. The Spanish also built Catholic churches on Indigenous religious sites. In this process, the Spanish created religious, educational, and medical institutions that cemented their presence in America. Many of these sites still exist today (Butler et al., 2007).

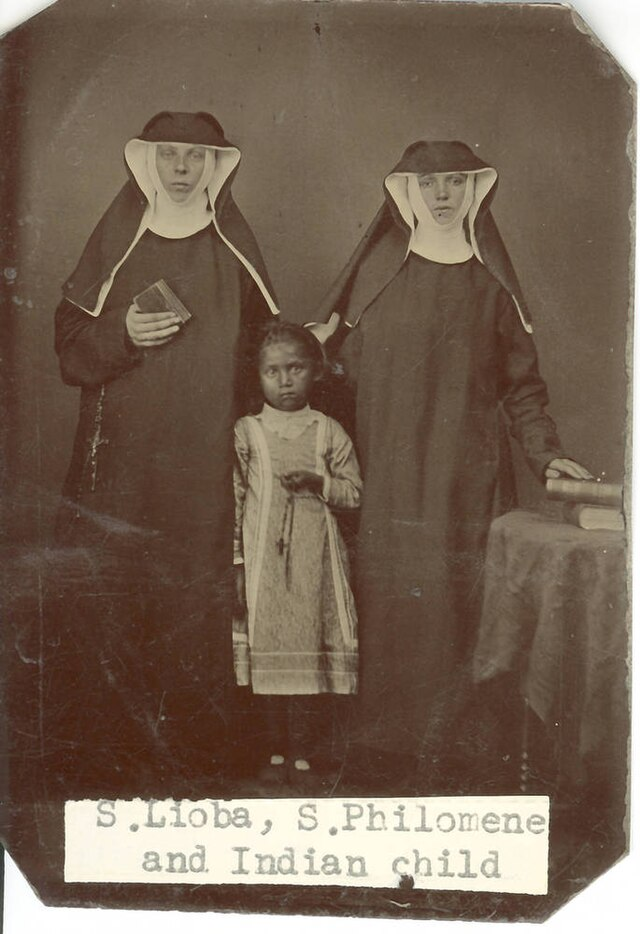

Conversion Tactics

The English, Spanish, and later French colonists used different tactics to convert Indigenous people to Christianity, with varying results. In many areas, conversion was violent and resistance was violently squelched. In other areas, such as modern-day Eastern Canada and parts of the Southwest, colonists worked to integrate themselves into Indigenous tribes as part of their conversion tactics (Butler et al., 2007).

No matter how colonists tried to convert them, Indigenous tribes continued to reject Christianity. However, with long-term exposure to Western religion, there was some integration of Indigenous and Christian practices. As time went by, Indigenous generations were born who were only exposed to Western religions and the colonists’ way of life, and some second and third generations of Indigenous people adhered to Christian principles without the need for conversion (Butler et al., 2007).

Shifting Priorities

Religious influence decreased as priorities in the colonies shifted, and in some areas such as Boston, many did not affiliate with any specific religion. While more than 90% of English colonists were Congregationalist or Anglican before 1690, no single religion could claim more than 20% as members by 1770. In addition, magic and other kinds of folk religions were becoming fashionable amongst the colonists. Trade and economic growth slowly became more important than religion to many living in the United States. The Puritans, in particular, felt this decline as Baptist, Presbyterian, and Quaker congregations competed for followers (Butler et al., 2007).

Indigenous People and Religion

Indigenous people practiced their religions for centuries in the Americas prior to the arrival of European settlers. Much of the genocide of Indigenous people in what is now the United States, including the forcing of Indigenous children into boarding schools, occurred because of religious conversion efforts.

Did you react to the word genocide as a description of what happened to Indigenous populations? I use this word intentionally after listening to a speech by David Treuer, an Indigenous writer. He asked us to use the proper terminology for what happened to his people when we talk about the history of the United States. He specifically and intentionally called it genocide. I encourage you to reflect on this and consider changing your terminology, too.

Discussion Questions

- What kind of reaction do you have to the word genocide? Why do you think you have it?

- Did you learn differently about what happened to Indigenous people in this country?

Butler et al. (2007) states that less is known about historical Indigenous religious practices than Christianity. What is known is that many Indigenous religions were holistic and did not separate the secular and the sacred. Thus, Indigenous religious beliefs were integrated into day-to-day life. Many Indigenous religions focused on the relationship with nature and many Indiginous rituals included spirits, visions, and dreams (Martin, 1999). Keegan (2022) warns that many scholars oversimplify Indigenous religions, often because the written history we do have is from missionaries who perpetuated Indigenous stereotypes.

So-called Indian boarding schools were a primary factor in the decimation of Indigenous culture and religion. Beginning in the late 1800s, the United States government forced hundreds of thousands Indigenous children into Indian boarding schools. By 1926, 86% of Indigenous children were in some sort of boarding school. At these schools, Indigenous children were forced to learn and conform to Christianity and Western culture (The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, n.d.). These boarding schools, most of which were in the Western part of the United States, were “the dominant form of Indian education in the United States for 50 years” (Waxman, 2022, p. 1).

Video: PBS: Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools

Discussion Questions

- How did Indian boarding schools impact the perception White Americans had of Indigenous people’s religious beliefs?

- How do you think the religious beliefs of Indigenous people were impacted by the Indian Boarding Schools?

Historically, Indigenous tribes did not receive First Amendment protections of religious freedom because their belief systems did not fit into Christian definitions of religion (Pluralism.org, 2020b). As Indigenous communities were forced onto reservations and their children moved into boarding schools, laws and policies were implemented to continue to prohibit their freedom to practice religion. In 1883, the Code of Indian Offenses was implemented. The code established Western-style law on the reservations. However, it also prohibited Indigenous religious practices. Tatum (2018) points out that this law, along with harsh penalties for practicing Indigenous religions, violated the First Amendment right to free exercise of religion.

In 1933, the Code of Indian Offenses was amended to reinstate Indigenous people’s right to dance. However, implementation was complex and intermittent. Often authorities on reservations withheld essential supplies, such as food, to coerce Indigenous people to not practice their religious ceremonies (Pluralism.org, 2020b). It was not until the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) in 1978 that the United States government acknowledged that federal policies were prohibiting Indigenous people from practicing their traditional religions. AIRFA protects the right of Indigenous people to practice traditional ceremonies, to access sacred ceremonial sites, and to possess sacred objects (Proctor, 2014). While AIRFA protects Indigenous religions on paper, the Supreme Court at the time of this writing has never ruled in the favor of Indigenous people when cases have been brought forth under AIRFA (Pluralism.org, 2020b; Tatum, 2018).

In 2015, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe stood their ground to stop the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline arguing that the pipeline cut through their sacred ground and violated AIRFA. The Supreme Court did not agree. Find a timeline here: Key Moments in the Dakota Access Pipeline Fight

Video: Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Takes Pipeline Fight to U.N.

Discussion Questions

- Do you think the pipeline violated AIRFA? Why or why not?

- What factors do you think influenced the decision of the Supreme Court in this case?

- Did the Supreme Court decision perpetuate historical religious discrimination against Indigenous people? Why or why not?

In an effort to align with the dominant Christian framework of the time and to assert their First Amendment right to religious freedom, tribal leaders in Oklahoma established the Native American Church of Jesus Christ in 1918 (Hinton, 2018). The church is still active today as a “loose confederation” (Pluralism.org, 2020a, para. 6). Their leaders are called Road Men and they continue to integrate Christian and Indigenous belief systems, including the ceremonial use of peyote (Pluralism.org, 2020a). In 1990, the Supreme Court did not protect members of the Native American Church in their peyote rituals, instead deferring to the laws of the State of Oregon, which considered peyote to be an illegal substance. Many feel this was in direct violation of AIRFA (Pluralism.org, 2020a).

Current trends in Indigenous religious practices in the United States have proven difficult to study. Often, religious polling excludes Indigenous religions and people. That said, research shows that most Indigenous religions still have commonalities such as deep kinship ties, community connection, ties to geographic place, and ties to the cycles of nature (Garroutte et al., 2014).

Discussion Questions

- In writing this section, I struggled to find information on the current experience in Indigenous people and religion—why do you think that might be? Do some research. What can you find?

- Do you agree or disagree with the Supreme Court ruling that peyote use is to be considered illegal drug use when considering employment? Why? What factors might be important in such a decision?

- How do you think discrimination and religion intersect in this population?

African Slaves and Religion

While many Europeans emigrated to the United States to practice their religion unobstructed, the enslavement of African people was a different kind of immigration. Slaves were seen as a commodity in the early United States and there was little effort to convert African slaves to Christian religions. Slave owners feared that slaves would see themselves as equal and revolt if introduced to Christianity. Due to these fears, African slaves were not allowed to form congregations. However, many African slaves practiced both native religions and Christianity in secret (Butler et al., 2007).

Enslaved African people practiced many religions in the early United States. Many African slaves continued to practice their local and traditional religions of West Africa. The West African religious practices varied; however, many included a single deity who was supreme and incorporated herbal medicine and charms (Mohamed et al., 2021). Despite being regularly practiced, none of the traditional African religious practices were able to be sustained in the United States (Butler et al, 2007).

Some of the slaves who arrived in the United States were already Christian or Muslim due to African colonization. As they were not allowed to form congregations, African Christian congregations developed their own style of worship, including the development of Christian worship songs based on the plight of the Israelites’ escapes from Egypt, which resonated with their slave experience (Mohamed et al., 2021).

Video: How Slaves Became Christian

Discussion Questions

- How do you think the experience of being a Christian as a slave was different from the experience of being Christian as a non-slave? Where did skin color or race fit into this experience?

- Describe another historical event where conversion happened in a similar way.

In the early 1800s, a freed Black slave, Richard Allen, started the first Black Protestant church, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Allen had been a Methodist preacher, but did not feel welcome in the church, so he decided to start his own. Similarly, the AME Zion church was founded in 1821. After the United States Civil War, the AME churches sent missionaries to the southern states to bring Black Christians into the Black churches.

Attendance in the AME churches swelled throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Beyond religious services, the AME church communities provided job training, insurance, reading materials, education, and athletic clubs. The AME churches were often the only places where Black people were allowed leadership roles (Mohamed et al., 2021).

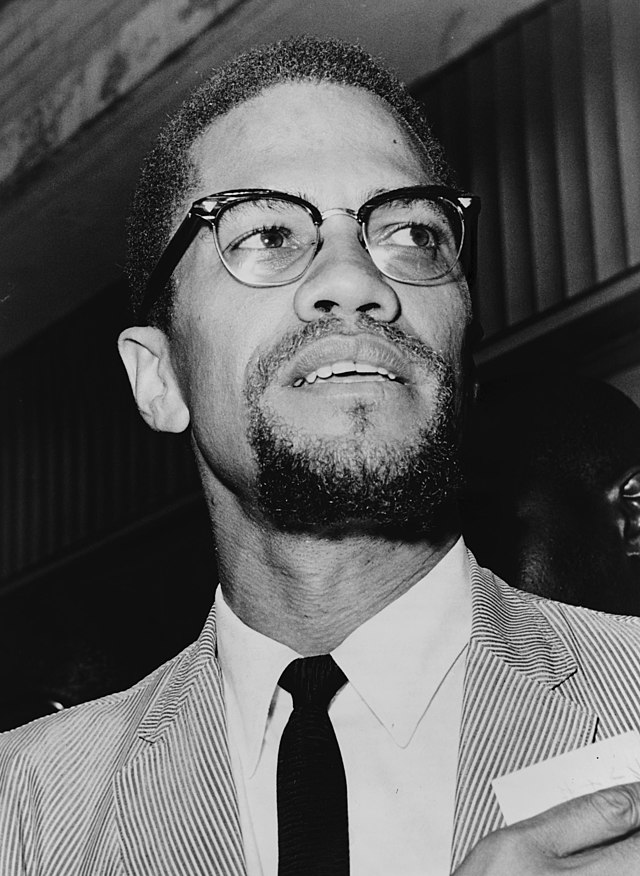

In 1930, the Nation of Islam was founded by Wallace D. Fard Muhammad which provided a foundation for Black nationalism in Islamic beliefs. Muhammad preached that God was Black and that the first man created in his image was also Black. Muhammad professed that Black people were the superior race (PBS, n.d.a). Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Nation of Islam actively built mosques in urban areas and recruited formerly incarcerated Black men. (National Archives, n.d.). The Nation of Islam has continued to be a religious presence in the United States and is currently led by Louis Farrakhan (Mohamed, 2021).

Malcolm Little, known as Malcolm X, converted to the Nation of Islam while in prison. Over time, Malcolm X shifted some of his beliefs, eventually splitting with the Nation of Islam in 1963. However, Malcolm X’s experience with the Nation of Islam impacted his belief that White people could not be trusted and that Black people should establish their own communities (UShistory.org, n.d.).

Discussion Questions

- What do you think of the idea that Black people should establish their own communities?

- How might religion have influenced the beliefs of Malcolm X and other civil rights leaders of his time?

In 1975, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was established, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King spoke out against racism and discrimination using both political and religious arguments. King believed that pluralism, or the coming together of many religions, was important to the civil rights movement (Whitaker, 2023). Although King is now viewed as a civil rights icon, at the time, many at the SCLC did not support his pluralistic ideals. Unsupported, King left the SCLC and, ultimately, founded the Progressive National Baptist Convention, which fully supported his civil rights efforts (Mohamed, 2021).

Video: Crash Course Black American History #36

Discussion Questions

- How did Dr. King contribute to the religious history of the United States?

- How did Dr. King contribute to the Social Justice movement through religion?

Currently, Black Americans are statistically more likely to be religious than non-Black Americans. However, religious affiliation is on the decline in all demographics. Of Black Americans who report that they do go to church, 60% say they do so in a predominantly Black church. This number is lower for younger Black Americans and higher for Black elders (Mohamed, 2021). “The research also shows that Black Protestants are the only Christian group in which a majority—63%—believes that congregations should get involved in social issues even if doing so means having difficult conversations” (DeRose, 2023, para. 9). DeRose reported this statistic is probably due to the historical involvement of Black churches in the civil rights movement.

Other Populations and Religion

While history often focuses on White, Christian settlers and religion, it must also be acknowledged that other cultures and religions came to the United States in a variety of ways. People other than Christian European settlers came to the United States in search of religious freedom as well. Borja (2021) states: “America has always been much more than a tri-faith nation of Protestants, Catholics and Jews” (p. 1). Their experiences were rich and complex, and these communities helped build the country the United States is today.

Borja (2021) points out that immigrants from Asian countries were present for much of the early history of the United States. “Chinese immigrants established the first Buddhist temple in the United States in San Francisco in 1853, and Sikhs built the first Gurdwara in the United States in nearby Stockton in 1912” (Borja, 2021, p. 1). The most often cited Eastern religions include Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Daoism, and Confucianism. As of 2020, around 1% of the population of the United States identifies as Buddhist and another 1% as Hindu. In addition, another 0.5%-1% of the US population identifies as “other,” which may include Eastern religions (PRRI, 2020). Eastern religions date back over 2000 years and generally refer to religious and philosophical practices that began on the continent of Asia (Harrison, 2019). Eastern religions are often framed philosophically, and Harrison points out that despite the conventional approach of lumping Eastern religions together, they vary in philosophy, belief, and cultural context across a large geographic region.

Interestingly, the trajectory of Eastern religions in the United States has been different from many other religions. There is less literature that discusses discrimination based on Eastern religious practices and more literature on the concerns around cultural appropriation of Eastern religious practices. For example, though Buddhism has seen a surge in popularity in the United States since the 1960s, many scholars point out that it is a White-centric, “Hollywood” version of Buddhism. While more than two thirds of Buddhists in the United States are Asian American, White voices dominate the religion (Kandil, 2021). Deshpande (2017) agrees, pointing out that her Hindi yoga practices, which are more than 2000 years old, have become a White-centric fitness practice.

Video: Cultural Appropriation

Discussion Questions

- Is Yoga/Buddhism as practiced in the United States cultural appropriation or cultural appreciation? Why?

- Is US Buddhism cultural appropriation or cultural appreciation? Or is it something different?

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints differs from some of the other religions because it was founded in the United States. Historically referred to as Mormons, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are Christians, yet its members have a history of being persecuted in the United States that continues today (PEW Research Center, 2012). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe in three levels of heaven and that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost are three separate gods versus the more traditional Christian concept of the Trinity (Harris, 2012; History.com, 2021). In the mid- to late 1800s, followers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were driven out from their midwestern homes by anti-Mormon sentiment. In 1844, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph Smith, was murdered by an anti-Mormon mob while incarcerated in Carthage, Illinois. In 1847, following Smith’s murder, a large group of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who had been driven from Illinois settled in Salt Lake City, Utah. They were led by Brigham Young (Harris; History.com). Currently, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints make up approximately 1.7% of the population of the United States and close to 50% of the population in Utah (Pew Research Center, 2009).

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a Style Guide that clearly outlines their official name and addresses the historical use of the word “Mormon” to describe their faith.

Discussion Questions

- Review the style guide—what surprised you about it?

- Why is it important to acknowledge and respect terminology from different religious groups?

- I struggled to decide how to word my writing in this section after reading the style guide. Was my use of the word Mormon (where I did use it) appropriate and respectful based on the guide? Why or why not? How might you have written this section differently?

In 2012, the Pew Research Center did an extensive study on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They found that 62% of followers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints felt that people in the United States are uninformed about their religion, and that nearly half felt that followers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints face discrimination in the United States due to their religion. Two-thirds felt that people in the United States do not see The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a part of mainstream American society (Pew Research Center, 2012).

Read an op-ed article: The Root: Is Broadway’s ‘Book Of Mormon’ Offensive? by Janice C. Simpson

Discussion Questions

- What do you think about parodying religion? Is this the same as discrimination? Why or why not?

- How do you think this musical contributes to stereotypes about followers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

- How do you think the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reacted to The Book of Mormon? Do some research to find out.

The United States is becoming more secular, and church attendance has recently fallen below 50% (Glasze & Schmitt, 2018). Approximately 29% of the population of the United States does not identify with any religion. This statistic has increased from previous surveys and is anticipated to continue to rise. Non-religious individuals identify as agnostic, atheist, or just identify as “nothing in particular” in survey data (Smith, 2021, para. 7). Glasze and Schmitt found that nonbelievers experienced significant discrimination when they shared their views with others. In addition, Glasze and Schmitt found that nonbelievers are often viewed with suspicion, seen as immoral or untrustworthy, and are perceived as pushing their nonbelief on others, particularly in workplace settings.

Atheism is the belief that God does not exist.

Agnosticism is the belief that we cannot know if there is a God. Because of this, most agnostics claim to neither believe nor disbelieve in God. (Mulhern, n.d.)

Video: Christian Discrimination for Praying in Public | What Would You Do?

Discussion Questions

- What do you think you would do in this scenario?

- What are the different sides of this issue?

- Where does the law fall on this issue?

- What are the ethics and morals of this issue?

- Do people have the right to pray in public?

Religion and Social Justice

While religious persecution has complicated history in the United States, religion has also played a significant role in social justice movements. The civil rights movement is an example (Cooper, n.d.). In addition, social justice is often seen as a moral imperative, and thus important in many religions. Religion often plays a role in social change and people like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, and Mahatma Gandhi all viewed social change through a religious lens. Other examples include the anti-slavery movement, welfare reform, and women’s suffrage (Cooper).

While religion is intertwined with social justice movements in many ways, it is difficult to separate out religious discrimination from other kinds of discrimination. The intersection of race, gender, ethnicity, and religion must be acknowledged. On the surface, the United States welcomes all religions; it is part of our Constitution and history as a country. Yet in examining the history of religion in the United States, the prominence of Christianity has clearly muddled the separation of church and state. Examples include our president swearing in on a Bible, Christmas as a national holiday, and “In God We Trust” being printed on our currency. Historically, there has not been equal treatment of religion under the law, and this is problematic in social justice movements.

In addition to the systemic issue of Christian influence in the United States, individual religious discrimination is also a complex experience. Again, intersecting identities make it hard to separate out religious discrimination versus other kinds of discrimination. Thus, someone who is Black may experience discrimination based on their race but not because they are Christian, and someone who is White may experience privilege because of their race but be discriminated against because they are a follower of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Last year, my friend’s son finished his freshman year in a public high school. He is a good student, plays sports, is active in music programs, and is an overall good kid. Unbeknownst to his mom, her son has been the target of serious antisemitism for years.

When my friend’s son was in 6th grade, he was getting ready for his bar mitzvah. He was exploring his Jewish identity and wanted to wear a yarmulke to school. His mom wasn’t sure about this for a variety of reasons; however, she supported his choice. He wore it for about a week, and within days he became the target of antisemitism. It started out with taunts like being called “Jew,” getting shoved in the hallway, and eventually being excluded from groups in gym class. Comments like “Don’t ask him to join us, he’s a Jew” were frequent. His mother contacted the school, and the antisemitic behavior stopped for a while, but would eventually start up again. He stopped telling her when it happened so she would stop calling the school.

Over the last few years, antisemitism towards him has increased and intensified into both verbal harassment and physical bullying. Comments like “Hitler was right,” and “Where is your yellow star armband?” and “cheap Jew” were frequent throughout his school day. My friend’s son got more and more anxious and depressed. He didn’t tell his mom that things were getting bad because he did not want to burden her. He finally confided in a friend who encouraged him to tell his mother. His mother called the school and was told that one of the boys in question had been suspended months prior for antisemitic bullying. She could not believe the school administrators never notified her.

My friend’s son just spent the summer in Israel, which was hopefully an empowering experience to get him through the rest of his high school experience. —Carrie, Jewish American

Discussion Questions

- How might the prolonged experience of antisemitism affect a young person’s mental health and self-esteem? What coping mechanisms might be helpful for this student?

- What responsibilities do schools have in preventing and addressing bullying, particularly when it involves hate speech and discrimination?

- What long-term strategies can be implemented to foster a more inclusive and respectful school culture?

- How does antisemitism in schools reflect broader societal issues, and what can be done at a community level to address these?

- What are some ways to educate students about diversity, tolerance, and the harmful effects of discrimination?

Religious discrimination happens often in the United States. Much like other forms of discrimination, religious discrimination can be overt and systemic or covert and individualized. There are entire books dedicated to religion and religious discrimination. However, for the purposes of this text, a choice had to be made in terms of what to highlight. Thus, while acknowledging that there are many other stories and experiences in the United States around religion, we have chosen to focus this section on two religions that are currently and glaringly experiencing discrimination. These are the Jewish and Muslim faiths.

Judaism in the United States

Judaism is one of the oldest religions in the world. There are 14 million Jewish people worldwide (History.com, 2023) and Jewish people make up 1–2% of the population in the United States (PRRI, 2021). Jewish people believe in one God who revealed Himself to ancient prophets and in the covenant between God and the Jewish people. Most Jewish people do not believe that Jesus was crucified and then raised from the dead three days later. Jewish people worship in synagogues and their spiritual leaders are referred to as rabbis. Their sacred text is the Tanakh. The Tanakh contains the same content as the Christian Bible’s Old Testament, but some of it is in slightly different order (History.com, 2023).

The Spanish Inquisition led to significant Jewish migration to the United States starting in 1492. During Colonial times, most Jews in the English colonies were Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. Jewish people settled in many metropolitan areas, such as New York City and Philadelphia, and began to establish synagogue-communities, which served the Jewish population in those cities. During the Civil War, there were Jewish people on both sides. However, xenophobic tensions increased during this time, and antisemitism and Jewish stereotyping surged. By the 1800s, the United States saw an infusion of Eastern European Jews, bringing the Yiddish language with them. Often these Ashkenazic immigrants had different religious tenets from the Jews already living in the developing United States, leading to some in-group discrimination (Sarna & Golden, n.d.).

The Holocaust Museum (n.d.) defines Antisemitism as “prejudice against or hatred of Jews” (para 1). Antisemitism has occurred since ancient times and scholars argue that the source of this antisemitism goes back to the role that Jewish people played in the crucifixion of Christ. This attitude shifted some in 1965 when, at a meeting of the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church repealed the theme of Jewish responsibility for the crucifixion. The term “Judeo-Christian tradition” resulted from this meeting (Anti-Defamation League, 2023).

In a recent survey, 26% of Jewish college students and 10% of Jewish workers struggled to take time off for Jewish holidays (Huffnagle & Bandler, 2023).

Discussion Questions

- Is it fair that Jewish people do not officially get their holidays off? Why or why not?

- Why do we celebrate Christmas as a national holiday and not Hanukkah?

- How would you feel if we no longer recognized Christmas as a national holiday?

Hernandez (2021) states that nearly one quarter of Jewish Americans experienced antisemitism in 2020. The Anti-Defamation League (2023) states that in 2022 they recorded the highest number of antisemitic incidents since 1979 and, in 2022, a report by Tel Aviv University found that antisemitism is rising in the United States (Associated Press, 2023). Huffnagle and Bandler (2023) referred to this trend as “The mainstreaming of antisemitism in American society” (para. 3). Examples of antisemitic incidents include vandalism, harassment, and assault (Shveda, 2023). Interestingly, this trend only seems to be happening in the United States. Other countries with large Jewish populations, such as England and Canada, have seen a decrease in antisemitism (Associated Press, 2023).

Jewish people continue to feel unsafe in the United States. In a 2022 report, the American Jewish Committee (AJC) found that antisemitism is felt on a deeply personal level. Often, protecting oneself from antisemitism involves a suppression of personal identity, which in turn alters behavior. Examples cited included avoiding posting online content that clearly identified an individual as a Jew, avoiding wearing traditional Jewish clothing or accessories, and avoiding certain places or situations (Huffnagle & Bandler, 2023). Huffnagle and Bandler go on to state that American Jews feel less safe in America than they did the previous year, and that security at United States synagogues has increased.

The internet has become a place where antisemitism is a significant concern. Eighty-two percent of the population has observed antisemitism online. Huffnagle and Bandler (2023) state that

The prevalence of antisemitism online has made the virtual communications sphere, with its limitless reach, the leading space for anti-Jewish prejudice, conspiracies, and hatred, and younger American Jews are more likely to be experiencing this form of hate. (para. 17)

Of those who reported experiencing antisemitism online, 72% did not report it to the online platform. Many of the participants who were younger Jews felt physically threatened in their online interactions (Huffnagle & Bandler, 2023).

Research shows that visibly identifiable Jews—usually ultra-Orthodox Jews and younger Jews—are more targeted for antisemitism (Associated Press, 2023; Huffnagle & Bandler, 2023).

Discussion Questions

- What factors might contribute to the increased targeting of visibly identifiable Jews, particularly ultra-Orthodox and younger individuals, in acts of antisemitism?

- How should communities and policymakers address the specific vulnerabilities faced by visibly identifiable Jewish populations while promoting broader efforts to combat antisemitism?

Personal contact with Jews makes one more aware of antisemitism and decreases the likelihood of engaging in antisemitic behavior (Huffnagle & Bandler, 2023). In addition, Davis (2022) recommends that individuals call out antisemitism when they see it. This may be in larger public and political spaces, such as cutting contracts with celebrities who make antisemitic remarks, or in personal settings, such as pointing out when someone makes antisemitic comments or jokes. In addition, Davis points out that when the media gives someone a platform for their antisemitic views through continuous news coverage, this may amplify those views. He recommends that those in power who make antisemitic statements be called out and publicly denounced.

Video: How Has Life Changed for Jews in America?

Current Research: Huffnagle and Bandler (2023) state that the more an individual knows about the Holocaust, the more likely they are to recognize antisemitism. In addition, having knowledge of the Holocaust increases recognition that antisemitism is rising.

Discussion Questions

- How did you learn about the Holocaust?

- Does your knowledge of the Holocaust increase your recognition of antisemitism? Why or why not?

- As history fades and the last of the Holocaust survivors die, how might this impact antisemitism in the United States?

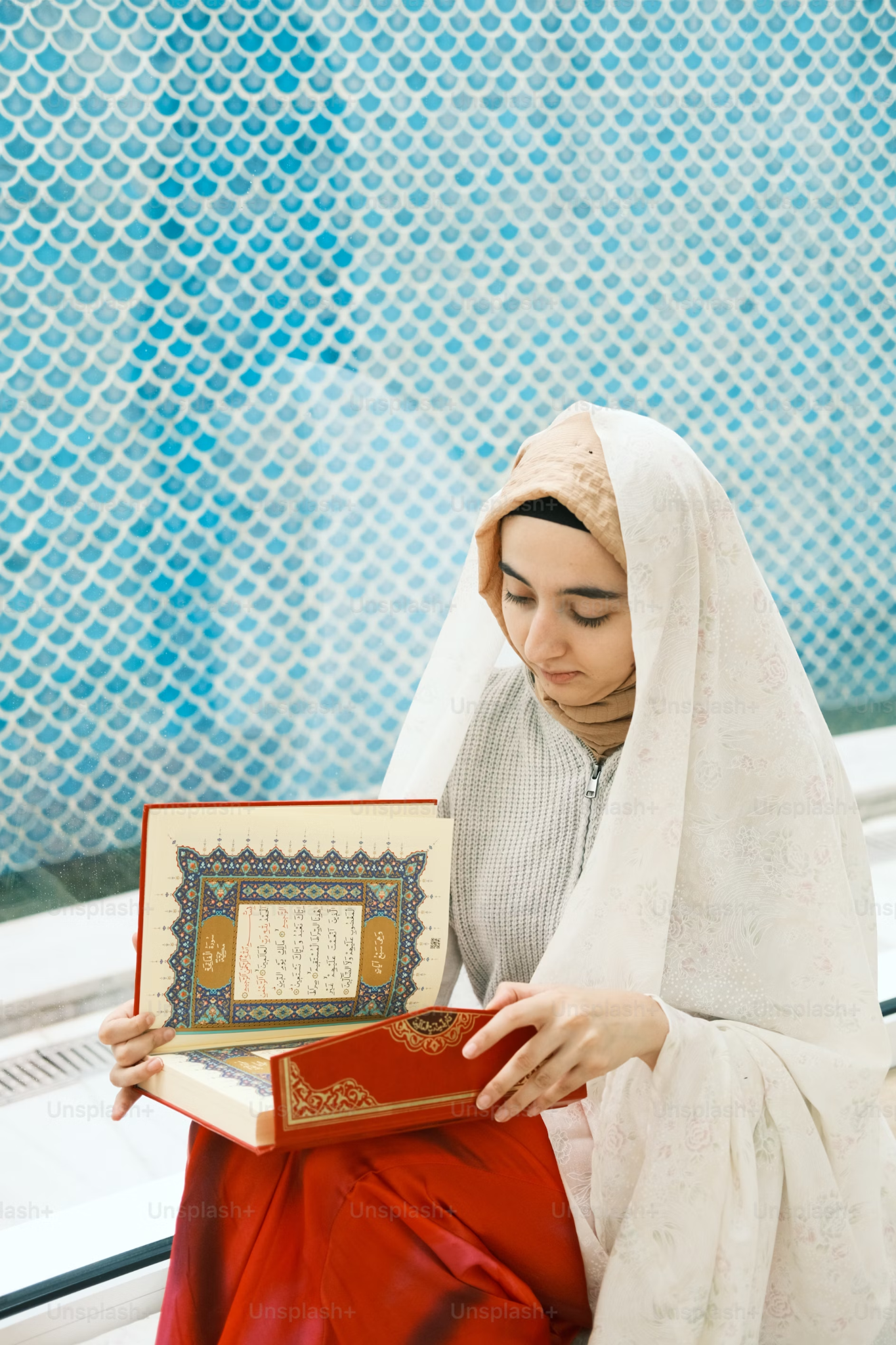

Islam in the United States

Islam is also one of the dominant world religions. Those who practice Islam are called Muslims. It is not clear when the first Muslims arrived in the United States. Many point to African Muslims brought as slaves. However, some argue that small pockets of Muslims arrived in the Americas by the 14th century. Between 1878 and 1924, the United States saw a surge of Muslim immigrants from the Middle East, many of whom settled west of the original 13 colonies. By 1952, there were more than 1,000 mosques in the United States (PBS, n.d.b).

Muslims believe there is one God and many prophets, the last of which was Muhammad. In Islam, God is called Allah and the place of worship is called a mosque. Muslims have six major beliefs and five pillars (URI.org, n.d.).

The six major beliefs are

- Belief in one God—Allah

- Belief in the Angels

- Belief in three holy books—the Torah, the Bible, and the Qur’an.

- Belief in multiple prophets sent by God, which includes Jesus, who is seen as a prophet and not the son of God

- Belief in the day of judgment and life after death

- Belief in divine decree that everything happens with God’s permission but God has given people free will; God will question everyone when they die about how they lived (URI.org, n.d.)

The five pillars are

- Shahadah—the declaration of faith

- Salat—the five daily prayers

- Zakah—almsgiving of 2.5% of wealth to the poor and needy

- Sawm—fasting during Ramadan

- Hajj—pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime (URI.org, n.d.)

Muslims are about 1% of the total population of the United States. That said, Muslim population is forecasted to increase to 2.1% by the year 2025, which will equate to about 8.1 million Muslims in the United States. This anticipated increase is due to a combination of increased immigration from politically unstable Muslim countries and the generally young demographic of the Muslim population who are expected to have children in the United States (Constante, 2018). While Muslim and Middle Eastern or Arab are often used interchangeably, they are not interchangeable. Muslim communities in the United States include individuals from all ethnic groups. In addition, up to two thirds of all Arab Americans in the United States identify as Christian (Peek, 2011).

Sharia is the legal system of Islam. Sharia law is a way of life for Muslims and is based on the Qur’an, the Sunnah, and Hadith–all religious texts. If a law cannot be found in the text, a crime is taken to religious scholars. A formal ruling under Sharia is called a fatwa. Sharia is not static–it has changed over time and continues to evolve. Muslims see Sharia as an integral part of their faith, thus when Sharia law is stereotyped as a threat, it makes no sense to them (Ali & Duss, 2011; BBC News, 2021)

Discussion Questions

- Did you already know what Sharia law is?

- Where have you learned about Sharia law?

- What biases might you have had towards Sharia law?

- How might the media have influenced your understanding of Sharia law?

Being Muslim has become intertwined with being Arab or Middle Eastern in the United States, and it is often difficult to pull that intersectionality apart. Peek (2011) describes this well:

In the aftermath of 9/11, the media and public officials often used the terms “Muslim” and “Arab” interchangeably. This conflation of categories led to the perception among many that all Muslims are Arab and that all Arabs are Muslim. This is certainly not the case. Muslim is an identifier used to describe those who believe in the religion of Islam, and thus Muslims can come from any nation and be of any racial or ethnic background. An estimated 1.57 billion Muslims live in countries spanning the globe, and only about 20 percent of the world’s Muslims reside in Arabic-speaking countries. (p. 11)

The Pre-9/11 Experience of Being Muslim in the United States

Muslims were in the Americas before the colonies were established and have been in what is now the United States since the 14th century (PBS, n.d.b). That said, finding history of the Muslim population is difficult due to dominant Puritan influences and the slave trade. Interestingly, there are hints that Muslim culture influenced the Spanish colonists and that while the Muslim faith was looked upon with some suspicion, it also was integrated into some of colonial life (Haselby, 2019).

In the early 20th century, many Muslim families in developing countries sent children to college in the United States. Some of these students remained in the United States, and pockets of American Muslim communities continued to grow in most major cities. As of 2011, nearly 60% of American Muslims had college degrees, including a significant portion of Muslim women. Thus, American Muslims are less likely to experience poverty and many work in well paying, professional jobs (Peek, 2011).

Despite this economic success, the stereotypes of Muslims were persistent even before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Many of these stereotypes were derived from film and television. Depictions of Muslims in the media included equating the Muslim daily prayer with guns and violence, the oppression of women, holy wars, and terrorism. Muslims were depicted as violent, primitive, and hateful (Peek, 2011).

Discussion Questions

- Did it surprise you to learn that Muslims were in the Americas before the original colonists? Why do you think that is not common knowledge?

- What role does education and income levels play in our assumptions about Muslim people?

- What kind of media depictions have you seen of the Muslim faith? How has this influenced your assumptions about people who practice Islam?

The Post-9/11 Experience of Being Muslim in the United States

Prior to the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2021, religious discrimination was the least reported type of discrimination (Dean, 2016). However, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 changed the relationship between Muslim and non-Muslim Americans in a variety of ways. Peek (2011) points out the negative role the media played in the experience of American Muslims following the attacks: “In the aftermath of 9/11, religious leaders, politicians, media pundits, and self-proclaimed terrorism experts exploited the feelings of an already-terrified citizenry by offering gross overgeneralizations and blatantly incorrect depictions” (p. 5).

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, discrimination towards American Muslims intensified and religious discrimination claims to the U.S. Department of Justice more than doubled (Dean, 2016). Americans started to perceive Islam as a threat, and many believed that Muslims wanted to kill all Christians and Jews. Muslims endured racial profiling, arrest, threats, bullying, harassment, and calls for Muslim bans. Anti-Muslim hate included the federal government raiding mosques, Muslims being denied boarding on planes, Muslim children being bullied, and American Muslims being discriminated against in the workplace. In addition, Arab men were arrested, detained without council, and deported (Peek, 2011).

Islam continues to grow in the United States with the number of mosques in the United States doubling between 2000 and 2020. In 2006 the first Muslim was elected to the House of Representatives. However, even more than 20 years after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, religious discrimination continues to be an issue for American Muslims, with 48% reporting they had personally experienced some sort of discrimination in 2017 (Mohamed, 2021).

Abuelezam et al. (2022) compared the experience of White and Middle Eastern college students. They found that college students who identified as Middle Eastern and had experienced discrimination struggled with increased depression and anxiety. White students and Middle Eastern students who had not experienced discrimination had fewer mental health symptoms. That said, Abuelezam et al. also found that being religious was a protective factor against depression and anxiety. So, while students of Middle Eastern descent were often targeted due to their religious and ethnic backgrounds, those who had strong religious convictions were able to manage that discrimination more effectively.

Discussion Questions

- What does this research tell us about the current experience of Middle Eastern college students?

- Why might religion be a protective factor for college students?

- What other factors might be contributing to the experience of Middle Eastern college students?

When people in the United States who are non-Muslim know someone who is Muslim, they are more likely to view Muslim individuals favorably. Personal contact with Muslim peers leads to people being more likely to both see Muslims as nonviolent and object to violations of their civil liberties. Research has shown that many people in the United States do not understand the Muslim faith and that this lack of understanding leads to more discrimination (Muhamed, 2021; Peek, 2011).

Discussion Questions

- Do you know anyone who is Muslim? How might that impact your assumptions towards people who follow Islam?

- How can we defend the civil rights of American Muslims? Give some examples.

- What implications does the research cited about knowing people who are Muslim have? How might we use this research to impact the experience of American Muslims?

Depictions of the Islamic Experience in the United States:

Thoughts from the Author

This chapter was one of the hardest to write for a variety of reasons. It got written, edited, re-written, discussed, and debated more than any other among me and my peers as I worked on this chapter. And sometimes I simply avoided it all together. It was just so much to take in. Working on this chapter became a United States history lesson I didn’t know I needed. I felt some strong feelings about the state of being Jewish or Muslim in the United States, and I hope you do too. And I found some of my biases that I need to work on, too. I learned so much in writing this chapter and couldn’t fit all information and nuances I wanted to; I encourage students to learn more.

Sincerely,

Dr. DeJonge (Bernie)

- What did you learn about the history of religion in the United States? How might this learning impact how you view religion in the United States today?

- How does religion connect with social justice?

- How does your religious upbringing (or lack thereof) affect how you view people of different religions?

- What are your thoughts on the inclusion of atheism and agnosticism in this chapter? Do they belong here? Why or why not?

- How can we decrease antisemitism in the United States? How can you decrease it personally?

- How can we decrease hatred against Muslims in the United States? How can you impact it personally?

References

Abuelezam, N. N., Lipson, S. K., Awad, G. H., Eisenberg, D., & Galea, S. (2022). Depression and anxiety symptoms among Arab/Middle Eastern American college students: Modifying roles of religiosity and discrimination. PLOS One, 17(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276907

Ali, W., & Duss, M. (2011, March 31). Understanding Sharia law. CAP. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/understanding-sharia-law/

Anti-Defamation League. (2023, Match 23). Audit of antisemitic incidents 2022. ADL. https://www.adl.org/resources/report/audit-antisemitic-incidents-2022

Associated Press. (2023, April 17). Antisemitic incidents on rise across the U.S., report finds. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/antisemitic-incidents-on-rise-across-the-u-s-report-finds

BBC News. (2021, August 19). What is Sharia law? What does it mean for women in Afghanistan? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-27307249

Borja, M. (2021, May 3). How Asian American religious history changes how we write American religious history. Patheos. https://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2021/05/how-asian-american-religious-history-changes-how-we-write-american-religious-history/

Butler, J., Wacker, G., & Balmer, R. (2007). Religion in American life: A short history. Oxford University Press.

Congress.gov. (n.d.). First Amendment explained. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-1/

Constante, A. (2018, January 9). Muslim projected to be the second-largest U.S. religious group by 2040. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/muslims-projected-be-second-largest-u-s-religious-group-2040-n836191

Cooper, Z. (n.d.). Christianity’s long history of social justice. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/03/christianitys-long-history-in-fighting-for-social-justice

Davis, K.C. (2010, October). America’s true history of religious tolerance. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/americas-true-history-of-religious-tolerance-61312684/

Davis, W. (2022, December 1). How to address antisemitic rhetoric when you encounter it. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/12/01/1139929829/how-to-address-antisemitic-rhetoric-when-you-encounter-it

Dean, K. L. (2016, May 17). Religious discrimination is “un-American.” [Video]. Tedx Talks. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7365IO9l-tw

DeRose, J. (2023, May 16). The importance of religion in the lives of Americans is shrinking [Radio broadcast]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/16/1176206568/less-important-religion-in-lives-of-americans-shrinking-report

Deshpande, R. (2017, October 27). Yoga in America often exploits my culture-but you many not even realize it. Self. https://www.self.com/story/yoga-indian-cultural-appropriation

Garroutte, E. M., Anderson, H. O., Nez-Henderson, P., Croy, C., Beals, J., Henderson, J. A., Thomas, J., & Manson, S. M. (2014). Religio-spiritual participation in two American Indian populations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(1), 17-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12084

Gjelten, T. (2017, June 20). To understand how religion shapes America, look to its early days [Radio broadcast]. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/06/28/534765046/smithsonian-exhibit-explores-religious-diversitys-role-in-u-s-history

Glasze, G., & Schmitt, T. M. (2018). Understanding the geographies of religion and secularity: On the potentials of a broader exchange between geography and the (post-) secularity debate. Geographica Helvetica, 73, 285-300. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-73-285-2018

Harris, D. (2012). What do Mormons believe? ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/mormons-%09/story?id=17057679.

Harrison, V. S. (2019). Eastern philosophy: The Basics (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Haselby, S. (2019, May 20). Muslims of early America. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/muslims-lived-in-america-before-protestantism-even-existed

Hernandez, J. (2021, October 26). 1 in 4 American Jews say they experienced antisemitism in the last year. NPR. https://www.kcrw.com/news/shows/npr/npr-story/1049288223

Hinton, C. (2018, October 10). Native American church marks 100 years. The Oklahoman. https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/religion/2018/10/10/native-american-church-marks-100-years/60496231007/

History.com. (2023, August 11). Judaism. https://www.history.com/topics/religion/judaism

History.com. (2021, October 7). Mormons. https://www.history.com/topics/religion/mormons

Huffnagle, H., & Bandler, K. (2023). The state of antisemitism in America 2022: Insights and analysis. American Jewish Committee. https://www.ajc.org/news/the-state-of-antisemitism-in-america-2022-insights-and-analysis

Kandil, C. Y. (2021, July 9). Young Asian American Buddhists are reclaiming narrative after decades of white dominance. NBC news. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/young-asian-american-buddhists-are-reclaiming-narrative-decades-white-rcna1236

Keegan, B. (2022). Contemporary Native American and Indigenous religions: State of the field. Religion Compass, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12448

Martin, J. W. (1999). The land looks after us: A history of Native American religion. Oxford University Press.

Mohamed, B. (2021, September 1). Muslims are a growing presence in U.S., but still face negative views from the public. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/09/01/muslims-are-a-growing-presence-in-u-s-but-still-face-negative-views-from-the-public/

Mohamed, B., Cox, K., Diamant, J., & Gecewicz, C. (2021, February 6). A brief overview of Black religious history in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/a-brief-overview-of-black-religious-history-in-the-u-s/

Montana.gov. (n.d.). ICWA history and purpose. https://dphhs.mt.gov/cfsd/icwa/icwahistory#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Child%20Welfar%20e%20Act,placed%20in%20non%2DIndian%20families

Mulhern, K. (n.d.). What is the difference between an atheist and an agnostic? Patheos. https://www.patheos.com/answers/what-is-the-difference-between-an-atheist-and-an-agnostic

National Archives. (n.d.). The Nation of Islam. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/nation-of-islam

PBS. (n.d.a). Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/malcolmx-elijah-muhammad-and-nation-islam/

PBS. (n.d.b). Islam in America. https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/islam-in-america/

Peek, L. (2011). Becoming Muslim: The development of a religious identity. Oxford University Press.

Pew Research Center. (2009). A portrait of Mormons in the U.S. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2009/07/24/a-portrait-of-mormons-in-the-us/

Pew Research Center. (2012). Mormons in America-Certain of their beliefs, uncertain of their place in society. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/01/12/mormons-in-america-executive-summary/

Pluralism.org. (2020a). Native American church. The Pluralism Project: Harvard University. https://pluralism.org/native-american-church

Pluralism.org. (2020b). Religious freedom for Native Americans. The Pluralism Project: Harvard University. https://pluralism.org/religious-freedom-for-native-americans

Proctor, E. (2014). What is the Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978? MSU Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/what_is_the_indian_religious_freedom_act_of_1978

PRRI. (2020). The American religious landscape in 2020. https://www.prri.org/research/2020-census-of-american-religion/

Ryman, H. M., & Alcorn, J. M. (2009). Establishment clause (Separation of church and state). The First Amendment Encyclopedia. https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/establishment-clause-separation-of-church-and-state/

Sarat, A. (Ed.) (2012). Legal responses to religious practices in the United States: Accommodation and its limits. Cambridge University Press.

Sarna., J. D., & Golden, J. (n.d.). The American Jewish experience through the nineteenth century: Immigration and acculturation. National Humanities Center. https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/judaism.htm

Shveda, K. (2023, March 23). Antisemitic incidents in the US are at the highest level recorded since the 1970’s. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/23/us/antisemitism-report-unprecedented-rise-dg/index.html

Smith, G. A. (2021, December 14). About three-in-ten U.S. adults are now religiously unaffiliated. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/12/14/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-are-now-religiously-unaffiliated/

Tatum, M. (2018, February 20). No religious freedom for traditional native religions. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/no-religious-freedom-for-traditional-native-religions

The Holocaust Museum. (n.d.). What is antisemitism? https://www.ushmm.org/antisemitism/what-is-antisemitism

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. (n.d.). US Indian boarding school history. https://boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. (n.d.). Know your rights: Title VI and religion. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/know-rights-201701-religious-disc.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Civil Rights Requirements- A. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq. (“Title VI”). https://www.hhs.gov/civil-rights/for-individuals/special-topics/needy-families/civil-rights-requirements/index.html

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). (n.d.) Religious discrimination. https://www.eeoc.gov/religious-discrimination

Ushistory.org. (n.d.). Malcom X and the Nation of Islam. https://www.ushistory.org/us/54h.asp

URI.org. (n.d.). Islam: Basic beliefs. https://www.uri.org/kids/world-religions/muslim-beliefs

Waxman, O. B. (2022, May 17). The history of Native American boarding schools is even more complicated than a new report reveals. Time. https://time.com/6177069/american-indian-boarding-schools-history/

Whitaker, R. (2023). MLK’s version of social justice included religious pluralism – a house of many faiths. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/mlks-vision-of-social-justice-included-religious-pluralism-a-house-of-many-faiths-197785

Media Attributions

- Religious Symbols © Shiva is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Ojibwe child is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Dakota Access Pipeline © Fibonacci Blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- First AME Church © Jeffrey Beall is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Malcolm X © Library of Congress is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MLK Jr. © O. Fernandez is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Book of Mormon © André-Pierre du Plessis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Menorah © Ted Eytan is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Quran © Nina Zeynep Güler is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- End Islamophobia © Fibonacci Blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license