7 Race: Being Asian, Indigenous, and Latinx in the United States

Bernadet DeJonge and Nikki Golden

- The reader will be able to describe race as a social construct.

- The reader will be able to identify historical events that have impacted the experience of being Asian, Indigenous, and Latinx in the United States.

- The reader will be able to connect systemic racism to current social justice movements.

It is essential to understand that systemic racism plays a significant role in contributing to social injustice in the United States. Racial injustice, which has roots in slavery and genocide, remains an essential issue in the United States today. Achieving social justice requires Americans to recognize and address systemic racism. This chapter explores the social concept of race, examining its historical evolution and impact in the United States through the lens of three racial populations.

Race as a Social Construct

Race is not rooted in biology; it is a social construct created by humans. The current concept of racial categories is a relatively recent development in human history (Kendi, 2016). In the English colonies, before racial categories had solidified, religious beliefs often determined people’s social status (Wilkerson, 2023). However, “the foundations of race and racist ideas were laid” (Kendi, 2016, p. 18). In the United States, racial categories are so deeply embedded in humans’ collective consciousness that even when confronted with science, “some human beings continue to perceive other human beings as excluded from the moral order of personhood” (Zimbardo, 2008, p. 307).

The National Human Genome Research Institute defines race as “a social construct used to group people. Race was constructed as a hierarchical human-grouping system, generating racial classifications to identify, distinguish, and marginalize some groups across nations and the world” (Bonham, 2024, para. 1). Categories of race, as used today, classify people into different groups based on observable and arbitrary physical characteristics, genetics, or other cultural differences (Bonham, 2024; Burton et al., 2010). Additionally, because race is a social construct, categorical definitions have been fluid, with determining factors based on need versus fact (Burton et al., 2010). In the United States, racial categories were created based on “European cultural values and traits, and hierarchy-making was wielded in the service of a political project: enslavement” (Kendi, 2016, p. 83).

The U.S. Census Bureau (2022) uses five categories to define race:

White – A person originating in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

Black or African American – A person who originates in any of the Black racial groups of Africa.

American Indian or Alaska Native – A person who originates in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment.

Asian—A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander—A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands (para. 1).

Discussion Questions

- Why do we track racial data in the United States? How might the data be used?

- Who is missing from the five categories? How do we account for those who do not strongly identify with a particular category?

- Latinx is identified as an ethnicity rather than a race. What is the difference between ethnicity and race? Where does Latinx fit in a discussion of race?

Populations

Racism permeates the experiences of those living in the United States. Although race is a social construct, its construction has “created racial realities with real effects” (Burton et al., 2010, p. 444). While race has no biological basis, it has historically been used to stratify society and impact access to resources. Socially constructed identities such as race are critical factors in predicting life experiences, including education, income levels, health and healthcare access, and access to other resources. Stratification based on race has led to oppressive systems and significant issues with racism in the United States and throughout the world (Grzanka et al., 2019).

Racism can be overt and systemic as well as covert and individualized. An entire book could be written dissecting these issues, and many have been. While acknowledging that there are stories and experiences from all racial groups in the United States, we have chosen to focus this chapter on those of Asian, Indigenous, and Latinx people in the country.

Being Asian in the United States

Historically, the term Asian has been used to broadly define people from East, South, Central, and West Asia. Examples include people from China, Vietnam, Japan, and Malaysia. People from the Asian continent have been immigrating to the United States since colonial times, bringing their culture and religious beliefs with them (Ling, 2023). Being Asian in the United States is complicated by historical events, including Westward Expansion, legislation, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese internment, racism, and recent events such as anti-Asian hate associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. As with other sections of this textbook, entire books can be written on this topic. We have chosen to highlight four dominant Asian groups in the United States: Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Indian.

Historical Aspects of Being Chinese in the United States

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, both Europeans and colonists wanted Chinese goods. Tea, silk, and porcelain were all status symbols, and demand was high. As soon as America became independent, the government began direct trade with China. “Trade routes between the United States and China were well established by the 1830s” (Ling, 2023, p. 11). Asian immigration, however, is generally seen as more of a trickle until the 1850s, when gold was discovered in California.

The gold rush of the 1850s brought large numbers of Chinese immigrants to the United States. Most were men, and most arrived in California, specifically San Francisco (Lepore, 2018). “In the early 1850s, the number of Chinese in America increased dramatically—2,716 in 1851 and 20,026 in 1852. By 1882, when the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act ended large-scale Chinese immigration, there were about 300,000 Chinese living in the United States” (Ling, 2023, p. 18).

Video: The Untold Story of Chinese Immigrants in the California Gold Rush

Discussion Questions

- How did systemic racism and legal discrimination manifest against Chinese immigrants during the Gold Rush era?

- How did Chinese immigrants create and sustain their communities despite facing significant adversity and exclusion?

- What forms of resistance and advocacy did Chinese immigrants and their allies engage in to fight against discrimination and injustice?

- How did the experiences of Chinese immigrants intersect with those of other marginalized groups during this time in United States history?

As with other ethnic and racial populations, stereotypes and rumors accompanied the Chinese men to the United States. Many saw Chinese laborers as a replacement for White laborers, and the term “yellow peril” came into fashion to describe this fear (Ling, 2023, p. 32).

“Yellow peril” referred to Western anxieties that Asians, particularly the Chinese, would take their land and undermine Western morals and values such as fairness, religion, and innovation. Additionally, stereotypes brought back from China by merchants, diplomats, and missionaries fueled anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. These stereotypes portrayed the Chinese as peculiar, eating dogs, cats, and rats, being dirty and arrogant, practicing infanticide, and being un-Christian.

Video: Chinese Slaves in America-Forgotten History

Discussion Questions

- Compare and contrast the experiences of Chinese laborers with those of African slaves. What was similar? What was different? What led to these differences?

- What methods were used to coerce Chinese individuals into labor, and how did these methods differ from other forms of slavery?

- What challenges exist in documenting and acknowledging the history of Chinese slavery in the United States? How do we address these challenges?

- What steps can be taken to acknowledge and rectify the historical injustices faced by Chinese laborers in the United States?

The marginalization of the Chinese during the 1800s and 1900s involved more than just discrimination and slavery. Laws, policies, and taxes aimed at Chinese immigrants also impacted their experience in the United States. The first was a tax levied in California called The Foreign Miners’ License Tax. This tax required foreign miners to pay $2.50 a month to the government of California. While originally meant to exclude all foreign miners, this tax ended up becoming directed specifically against Chinese immigrants. “Between 1850 and 1970, the state collected five billion dollars, with nearly 95 percent paid by the Chinese” (Ling, 2023, p. 34). Nevada also taxed foreign miners, and Ling (2023) estimates as much as 96% of Chinese immigrants’ income was used to pay taxes during that time.

In 1860, inspired by the Foreign Miners’ Tax, a tax on Chinese immigrant fishermen was levied in California. Following this, other taxes targeting Chinese immigrants continued to be levied, such as taxes on small mass shrimp nets and laundromats, and head taxes, which taxed Chinese people coming into the harbor. In addition, alien land laws discouraged Chinese immigrants from settling in rural Western and Midwestern areas. California enacted the Alien Land Law in 1913, and many Chinese farmers had to put land in their children’s names or form a corporation under White attorneys to own land. Some scholars speculate that this may be why many Chinese immigrants ended up in more urban areas (Ling, 2023).

In addition to racist tax policy, exclusionary legal precedent also occurred during this time in United States history. Ling (2023) points out that hundreds of Chinese men were murdered during the first five years of the gold rush. One of those was Ling Sing. On August 9, 1853, a White miner named George Hall shot and killed Ling Sing, who was also a miner. Hall was convicted of the murder. Hall appealed his conviction, and the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Hall that “Asiatics” could not testify against White citizens in court (Ling, 2023, p. 36). The California Supreme Court then overturned Hall’s conviction. This decision was based on existing law that prevented both Black and Indigenous people from testifying in court (Blakemore, 2024, April 23).

People v. Hall set the stage for violence without consequence against Chinese immigrants. Tax collectors would tie up Chinese miners, often with their hair, and steal their tools, boots, and belongings. White miners would assault and murder Chinese men without consequences and often resorted to arson. Violence erupted in many Western cities, including Los Angeles, Denver, Tacoma, Seattle, and Bellingham (Washington), and Rock Springs (Wyoming) (Ling, 2023).

Racist attitudes soon spread to the urban areas of California as well, and Chinese immigrants were often forced to live outside city limits.

In 1858, the mayor of Mariposa, California, ordered that no one rent to the Chinese, as they cooked over open fires, lit firecrackers on holidays, and burned joss sticks before their gods. He declared Chinatown a fire hazard and that it should be demolished (Ling, 2023, p. 36).

Video: Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871

Discussion Questions

- What were the short-term and long-term effects of the massacre on the Chinese community in Los Angeles and the United States?

- How did racial tensions and xenophobia against Chinese immigrants manifest in Los Angeles before and after the massacre?

- How does the Chinese Massacre of 1871 compare to other acts of racial violence in United States history, such as the Tulsa Race Massacre or the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II?

- What lessons can be drawn from the Chinese Massacre of 1871 in addressing contemporary issues of racism, xenophobia, and violence against minority communities?

Immigration Policy and Exclusion

The first national exclusion law aimed at Asian immigration was the Page Act of 1875. The Page Act was aimed at preventing both laborers and women from entering the United States from the Asian continent, but was primarily enforced against Chinese immigrants. It was commonly believed that most Chinese women coming into the United States did so as prostitutes. The Page Act required all women entering the United States to prove they were not prostitutes, and this often led to invasive and humiliating questions from United States immigration officials, who were given the power to admit or deny immigrants. The Page Act was relatively effective, and the gender imbalance in Chinese communities continued to skew male in the late 1800s. In addition, Chinese men were often discouraged from marrying outside their race, so many remained unmarried or returned to China (Rotondi, 2024).

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This was the first law to ban a specific ethnic group from entering the United States, barring the entry of Chinese laborers for 10 years. Merchants, diplomats, students, teachers, and travelers were exempt. Under this law, Chinese laborers were required to get certification to enter the United States, and Chinese immigrants were excluded from United States citizenship (Ling, 2023).

On October 1, 1888, Congress passed the Scott Act, which expanded the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Scott Act suspended the system of reentry for Chinese laborers who had left the United States and wanted to return, establishing a system where Chinese laborers had to get a certificate from the United States government to return. Many struggled to gain reentry, even with the certificates, and it is estimated that the racist implementation of this law prevented the reentry of 20,000 Chinese laborers.

The Geary Act of 1892 expanded the Chinese Exclusion Act even further, extending the exclusion of Chinese immigrants for 10 more years. It mandated that all Chinese residents in the United States carry their certificates, and thus placed the burden of proof to remain in the United States on them. The Geary Act continued to target Chinese women under the assumption that they were coming to the United States to engage in prostitution. The 1882 Exclusion Act was renewed in 1892 with the Geary Act, and again in 1902 when the restrictions on Chinese immigration were renewed indefinitely. The Geary Act regulated Chinese immigration well into the 20th century (Ling, 2023).

Following World War I, Congress established a new immigration policy based on the 1890 census, utilizing quotas based on national origin. The limit for new immigrants was 2% of the nationality already living in the United States. In 1943, the Magnuson Act repealed all the Chinese Exclusion Acts, as China was a member of the Allied Nations during World War II. However, the quotas remained unchanged, and the annual limit for Chinese immigrants to the United States at that time was 105 (National Archives, 2023).

The Immigration Act of 1965 changed the quota system. Instead of focusing on Chinese immigrants, the United States set a limit of 170,000 immigrants from outside the Western Hemisphere, with a maximum of 20,000 from any one country. Factors that influenced approval included needed skills and the need for political asylum. In 2011 and 2012, the House and Congress condemned the Chinese Exclusion Act (National Archives, 2023).

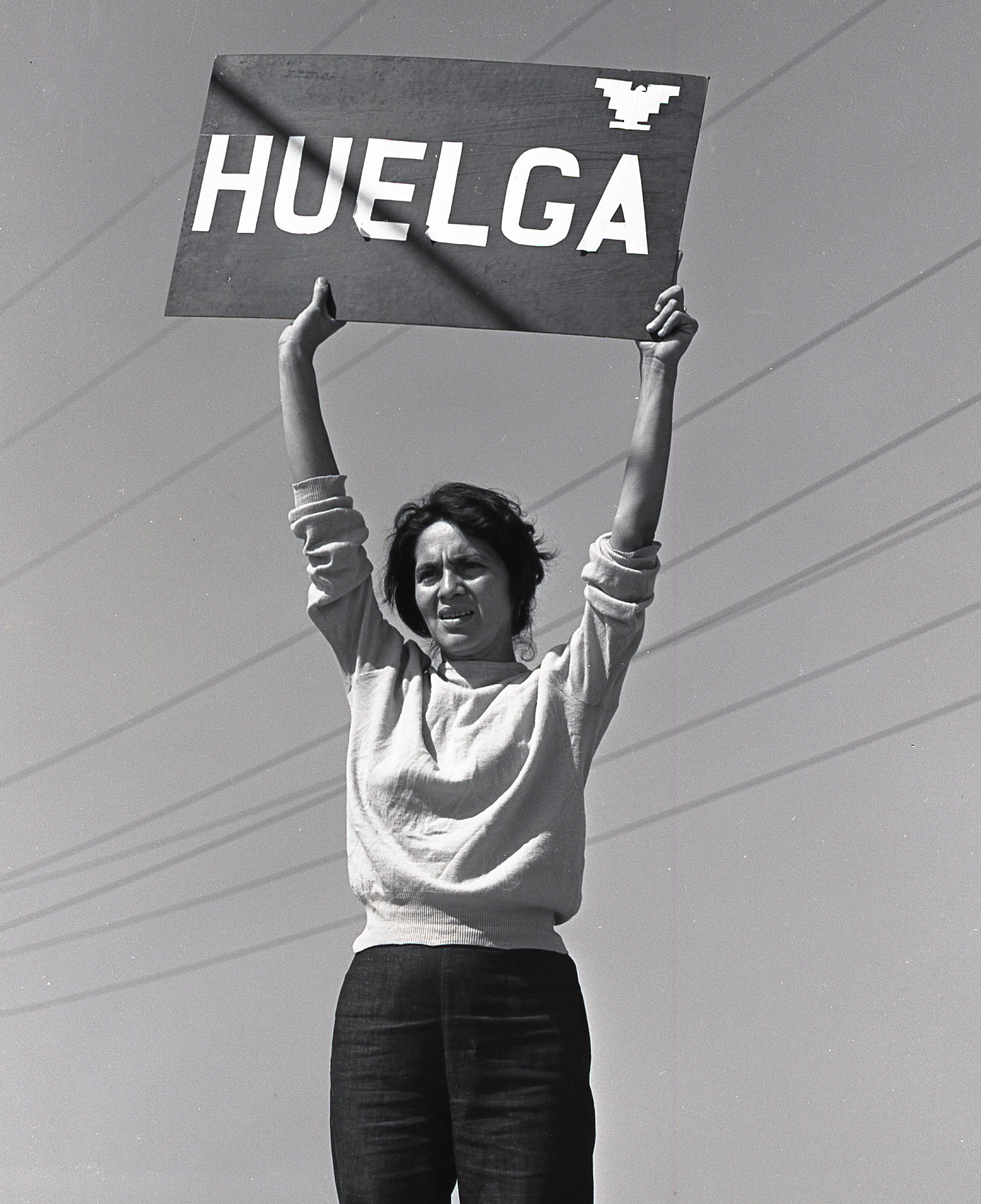

Resistance to exclusionary law and policy came both officially from Asian governments and unofficially from protests of those affected. To protest the Chinese exclusion laws and the violence against people of Chinese descent in the United States, China began a nationwide anti-American boycott. Millions of Chinese in China and abroad responded to the call to boycott American goods. On September 22, 1892, nearly 200 English-speaking Chinese from the East Coast rallied at the Cooper Union in East Village in lower Manhattan to form the Chinese Equal Rights League (Ling, 2023).

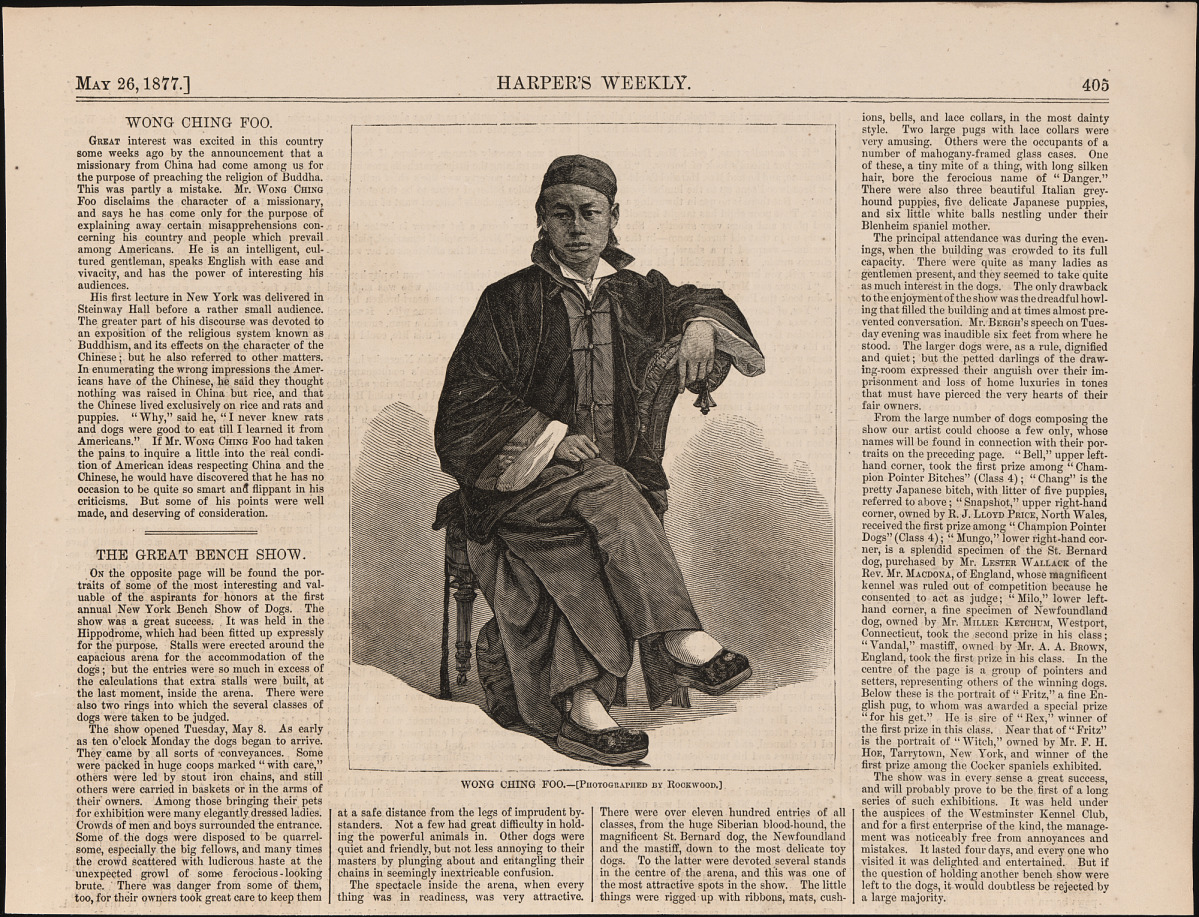

Video: Who Was Wong Chin Foo?

Discussion Questions

- Wong Chin Foo is often described as one of the first Chinese American civil rights activists. What does this mean in the context of United States history?

- Wong Chin Foo believed education was a form of activism. How did this show in the work he did? Was this an effective strategy? Why or why not?

- How does Wong Chin Foo’s activism compare to that of other civil rights leaders of his time? In what ways did his approach differ from or align with the strategies used by other marginalized groups seeking justice?

- How did Wong Chin Foo’s activism intersect with other social justice issues of his time?

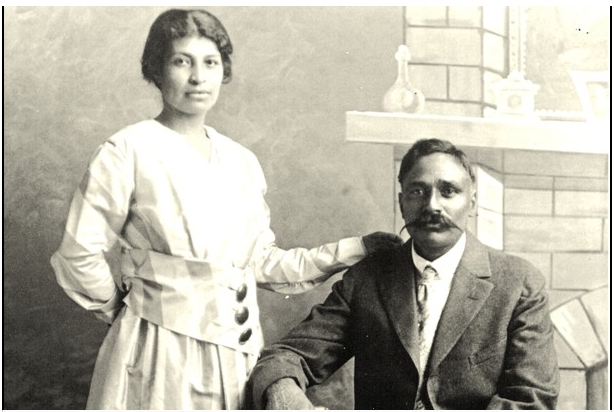

Wong Chin Foo was not the only person voicing opposition. There were a multitude of court cases filed in response to the exclusionary legislation. Two cases often cited in the literature are Takao Ozawa v. the United States in 1922 and the US v. Bhagat Singh Thind in 1923. Takao Ozawa was born in Japan but grew up in California. He was Christian, spoke English, and fully integrated into the culture of the United States. Ozawa filed for citizenship in 1922, arguing that he should be considered White because of his acculturation. The United States government argued that White refers specifically to those who are Caucasian, which does not include people from Japan. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled against Ozawa and held that White people and Caucasians were the same (Tanaka, n.d.).

In 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind applied for United States citizenship. Thind was an Indian Sikh living in the United States who had served in World War I for the United States. Thind argued in the US v. Bhagat Singh Thind that he was scientifically part of the Caucasian race as the racial classification at the time considered Aryan individuals to be Caucasian, and Thind identified as Aryan. The government countered with the argument that Whiteness should be interpreted as the common understanding of White in American culture, not the scientific classification. The United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled against Thind (Tanaka, n.d.).

- What were Takao Ozawa and Bhagat Singh Thind’s main legal arguments in their respective cases? How did each of them attempt to qualify as “White”?

- How did these two cases (Takao Ozawa v. the United States and the US v. Bhagat Singh Thind) contradict each other? Why are these contradictions important in understanding the history of race in the United States?

- What do the outcomes of these cases reveal about the role of the legal system in perpetuating racial exclusion and discrimination?

- In what ways are the issues raised in the Ozawa and Thind cases still relevant today? How do these historical cases inform current debates about race, citizenship, and immigration?

Historical Aspects of Being Japanese in the United States

The Japanese population in the United States experienced discrimination to their Chinese counterparts in the late 19th century. However, there were significantly fewer Japanese people in the mainland United States during that time. That said, between 1850 and 1920, more than 300,000 Asians emigrated to the Hawaiian Islands, most of them Japanese. Sugar production demanded labor, and much of that need was met by Japanese and other Asian workers. In the late 19th century, going to Hawaii to earn money to pay off debt became popular amongst Japanese farmers. Many Japanese people went to Hawaii and, in lesser numbers, the mainland United States as contract workers. Between 1895 and 1908, private companies brought more than 130,000 Japanese workers to the United States. Most of these workers, 85%, were male (Ling, 2023).

In 1908, after one and a half years of negotiation, the Japanese and American governments came to a gentleman’s agreement on immigration. This non-binding, non-legal agreement stated that the Japanese government would control emigration and would no longer send laborers to the United States. It could, however, send business professionals, students, and family members of people already residing in the United States. The United States agreed to ensure better treatment of Japanese immigrants already living in the United States and promised to address discriminatory practices impacting Japanese immigrants (Ling, 2023).

Website: Segregation of Japanese School Kids in San Francisco Sparks an International Incident

Discussion Questions

- What were the long-term effects of the gentleman’s agreement on Japanese immigration and Japanese American communities in the United States?

- What role did local, state, and federal governments play in either perpetuating or challenging racial segregation and discrimination against Japanese Americans?

- How did the segregation of Japanese schoolchildren reflect broader racial inequalities in the United States education system during the early 20th century?

One consequence of the gentleman’s agreement was the practice of bringing a picture bride to the United States. To enter the United States, a Japanese woman would marry her future husband in Japan by proxy and then join him in the United States as his wife. By 1908, more than 20,000 Japanese women had come to the United States as a picture bride. Starting in 1920, the Japanese government stopped issuing passports to picture brides (Ling, 2023).

Video: Rice & Roses Excerpts Picture Brides

Discussion Questions

- Why are personal stories about immigration essential to our understanding of history?

- How did United States policy and legislation impact the experience of picture brides and other Japanese immigrants?

Despite the gentleman’s agreement, life on the sugar plantations was hard. The living and working conditions were poor, and pay was low. By the 1870s, Japanese laborers significantly outnumbered the native Hawaiian and Chinese workers and were paid $10 to $15 a month. This contrasted with the average of $50 a month on the mainland. Plantation workers also lost wages to fines that were established to “discipline” them (Ling, 2023, p. 65). Drinking, gambling, fighting, insubordination, refusing work, trespassing, and breaking materials were all behaviors that could be fined. In addition to fines, Japanese workers faced whippings, beatings, and interethnic inequities intended to cause strife among workers as a form of control (Ling, 2023).

While systemic racism was used to control Japanese workers on sugar plantations, many still protested. Some resisted by calling in sick, minimizing their workload, or deserting their work before their contracts expired. Many Japanese workers also engaged in collective action, including multiple strikes. Generally, the strikes were organized by Japanese workers; however, at times, they collaborated with other Asian workers, including Chinese and Filipino workers. In response, plantation owners began to import workers from Korea. Korean workers did not engage with the Japanese workers due to animosity from Japan’s recent colonization of Korea, and the plantation owners took advantage of this (Ling, 2023).

Many Japanese workers moved to the mainland United States when their sugar plantation contracts expired. Between 1902 and 1906, almost 34,000 left Hawaii and settled in California and the Pacific Northwest. To support themselves, they sold fresh vegetables and fruit, engaged in retail work, or provided domestic service (Ling, 2023).

Video: The Japanese Immigrant Experience in America: First Half of 20th Century

Discussion Questions

- What were some key laws or policies that affected Japanese immigrants in the early 20th century? How did these policies impact their lives and communities?

- The video talks about Japanese immigrants dressing in Western-style clothing to fit into American culture. Did this work? Why or why not?

- How does the Japanese immigrant experience compare to other immigrant groups in the United States during the same period? What similarities and differences can be observed?

Japan entered World War I on the side of the Allied powers and became a global power due to its involvement in the war (Kiilleen, 2021). Japan and the United States had a history of diplomatic conflict over China and immigration; however, they came together for World War I. Once the war was won, however, conflict again erupted between the two nations (Office of the Historian, n.d.).

World War II began in 1939 with Germany’s invasion of Poland. While the United States did not immediately enter the war, it supported the Allied powers politically and financially. Tensions with Japan continued due to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and their full-scale invasion of China in 1937. In July of 1941, the United States imposed an embargo on oil exports to Japan in response to their aggression in Southeast Asia. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, a United States Navy base in Honolulu, Hawaii. The next day, the United States entered World War II by declaring war on Japan (History.com, 2010).

Video: The Attack on Pearl Harbor

Discussion Questions

- Why was the attack on Pearl Harbor a significant event in World War II history? What immediate and long-term impacts did it have on the United States and the world?

- Were there any efforts to hold individuals accountable for the attack on Pearl Harbor? Discuss the concept of justice in the context of this event.

- How has the historical interpretation of the attack on Pearl Harbor evolved over time? What are some of the differing perspectives among historians?

Ling (2023) points out that all Asian immigrants had faced discrimination in the United States; however, with the onset of World War II, public perceptions changed. “Chinese were now viewed as brave, heroic, honest, and hardworking allies, whereas Japanese were scorned as cowardly, conniving, and despicable enemies” (Ling, 2023, p. 107). Anti-Japanese sentiment reached “hysterical” levels (Ling, 2023, p. 108) following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Japanese American communities were subjected to government searches and confiscation of personal belongings in the name of national security.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the internment of Japanese Americans. With Executive Order 9066, more than 40,000 Japanese people living on the West Coast of the United States and 70,000 of their American-born children were forced from their homes into internment camps. This event occurred under the guise of military necessity; however, it was heavily influenced by both political and public pressure (Ling, 2023).

In March of 1942, the military declared that all enemy aliens in Washington, Oregon, California, and part of Arizona had to move. This included people who were German, Italian, and Japanese. The Japanese order also included anyone with Japanese ancestry. In practice, few Germans and Italians were forced to move. However, the Wartime Civil Control Authority forced the evacuation of more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry (Ling, 2023).

Japanese Americans who were removed from the West Coast were given a week to prepare for evacuation and internment. They were only allowed to take what they could carry with them. The military moved them on buses and trains to assembly centers, often racetracks or fairgrounds, to be sorted into camps. Ten permanent internment camps were established, mainly in the desert and mountain areas of the West (Ling, 2023). Two camps were also located in Arkansas (The National WWII Museum, n.d.). Each camp was built to accommodate an average of 10,000 people (Ling, 2023).

Life at the camps was brutal. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. Internees lived in army-style barracks, which offered little privacy or protection from the elements. Food and bathroom facilities were communal. Some Japanese men had jobs, including outside the camps, as farm workers. However, their compensation was significantly less than standard wages. As time went on, internees lost their homes and farms back home as they defaulted on mortgages (Ling, 2023).

While the Japanese internees had initially been cooperative with internment, resentment built over time. Protests erupted at the camps. The first occurred in November 1942, at Poston, Arizona. As internees performed most labor in the camps, the protest and subsequent strike were impactful. A larger mass protest broke out at Manzanar, California, on December 6, 1942 (Ling, 2023).

Interestingly, internment only occurred where Japanese people lived in small numbers. Japanese people in Hawaii did not face internment, as their removal would have devastated the Hawaiian economy. Ling (2023) also points out that

there were over a million unnaturalized natives of the Axis powers resident in the United States…all of whom were potential internees. However, Japanese people, two-thirds of them native-born citizens, were the only ones singled out for mass internment because of their smaller population and racial background. (p. 114)

Video: Ugly History: Japanese-American Incarceration Camps

Video: Why I Love a Country That Once Betrayed Me

Discussion Questions

- How can we evaluate the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II in terms of civil rights and constitutional protections? Discuss the balance between national security and individual freedoms.

- What were the psychological and social impacts of internment on Japanese Americans? Consider factors such as identity, trauma, and resilience.

- How did the internment affect Japanese American communities after the war ended? Discuss the challenges they faced in rebuilding their lives and reintegrating into American society.

- How does the internment of Japanese Americans compare to the treatment of other minority groups during times of national crisis? Consider similar instances in United States history or in other countries.

- How do personal narratives and testimonies from interned Japanese Americans contribute to our understanding of this period? What insights do they provide that might be missing from official records and histories?

In 1943, Japanese internees were subjected to loyalty tests. They were asked to renounce the Japanese emperor and state whether they would serve in the United States military. Many American-born Japanese people resented these tests and refused to cooperate, saying no to both questions. Those who did so, usually under protest, were labeled as disloyal and separated further from their families. As time went on, questions began to arise about why those who were deemed to be loyal were still interned. Pressure mounted for President Roosevelt to end the internment programs. He did so in December 1944 (The National WWII Museum, n.d.).

Video: Why Japanese Internment Still Matters Today

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think Japanese internment still matters today?

- What actions can individuals take to advocate for the rights of marginalized communities today, inspired by the lessons from Japanese American internment?

- What long-term effects did the internment have on Japanese American communities? How are these effects still felt today?

Most people released from the internment camps returned to the West Coast of the United States. When they returned, many had lost everything. Homes had been looted, businesses and farms seized. Anti-Japanese racism continued, and the newly released internees faced daily harassment and abuse, including violence. In addition, many were turned away at local businesses. In response, many Japanese Americans resettled again, building communities in Salt Lake City, Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit (Ling, 2023).

Video: The Redress Movement: Reclaiming Civil Liberties

Discussion Questions

- How significant was the formal apology from the United States government in the context of the Japanese Redress Movement? What impact did it have on the Japanese American community and American society as a whole?

- Compare the Japanese Redress Movement to other movements for reparations or justice for marginalized groups. What similarities and differences can you identify?

- What actions can individuals and communities take today to support similar movements for justice and redress for other marginalized groups? How can we ensure that past injustices are not forgotten and repeated?

On April 12, 1945, President Roosevelt died, and Harry Truman became his successor. In May 1945, Nazi Germany surrendered. However, Japan continued fighting and continued to inflict significant casualties on United States troops (History.com, 2010). In July 1945, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China met in Potsdam, Germany to discuss the terms for the end of the war. As part of these discussions, they called for Japanese to surrender in the Potsdam Declaration. When Japan rejected the declaration, the United States retaliated with two atomic bombs (Atomic Heritage Foundation, n.d.)

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. On August 9, 1945, the United States dropped the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Japan surrendered to the United States on August 15, 1945. Estimates suggest that more than 210,000 people were killed, either immediately or in the aftermath of the bombings (History.com, 2010). Following the bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the United States occupied Japan until 1952 (Ling, 2023).

Video: Remembering the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings, 75 Years Later

Discussion Questions

- What ethical arguments can be made for and against the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? What are the ethical implications of targeting civilians in military conflict?

- How can we evaluate the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in terms of international law and wartime conduct? Discuss the relevance of the Geneva Conventions and other legal frameworks.

- What lessons can be learned from Hiroshima and Nagasaki regarding the ethics and future of warfare? How do these events inform contemporary discussions on the use of military force and weapons of mass destruction?

- How do the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki compare to other acts of mass violence?

Historical Aspects of Being Indian in the United States

The initial emigrants from India to the United States came from the Punjab region. When the British annexed Punjab in 1849, they levied cash taxes on the local population, and many farmers lost their land. In response, people from Punjab either joined the British army or became migrant workers. Some of these migrants made the long journey from Punjab to the United States, where early Sikh migrants worked in lumber and railroads in California. Later, they turned to agriculture (Ling, 2023).

Video: What Is Sikhism?

Discussion Questions

- What is the difference between Punjabi and Sikhism?

- What Sikh traditions impact their experience of living in the United States? How do their religious beliefs impact acculturation?

Video: The Punjabi-Mexicans of California: The Unlikely Union of Two Communities

Discussion Questions

- How has Punjabi-Mexican heritage influenced the cultural landscape of California today? The United States?

- How does this story challenge or reinforce your understanding of American immigration and multiculturalism?

- How have the descendants of Punjabi-Mexican families contributed to American society?

Much like other Asian populations, migrants from the Punjab region were primarily men. Due to racial marriage laws and the lack of Sikh women in the United States, many Sikhs married Mexican women (Ling 2023).

Many Sikh men worked in railroad construction at the turn of the century. Between 1903 and 1908, 2,000 Punjabi laborers worked on the Western Pacific Railroad in Northern California, building the section between Oakland and Salt Lake City. Most of these laborers were single men who lived in bunkhouses and provided their own food in collective cookhouses (Ling, 2023).

Prior to 1965, there was a very small population of Sikh or Punjabi immigrants in the United States. Post-World War II, most immigrants from India were professionals or students, and fewer were laborers. When Congress abolished national origin quotas in 1965, Indian immigration to the United States increased rapidly. As of 2022, Indian immigrants are the second largest immigration group, following Mexicans. Interestingly, the United States has recently seen a significant jump in unauthorized Indian arrivals at the United States-Mexico border (Hoffman & Batalova, 2022).

Historical Aspects of Being Filipino in the United States

One of the oldest Asian American communities in North America was a Filipino community established in the 1760s, when a group of Filipino sailors established a settlement in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana (Ling, 2023). In 1898, the United States annexed the Philippines from the Spanish for $20 million at the Treaty of Paris. The Filipinos objected to this and rebelled. This led to the Philippine Insurrection, or the Philippine-American War, which lasted three years. In 1916, Congress promised the Philippines would have eventual independence and, in 1946, the United States granted the Philippines independence (Naval History and Heritage Command, 2023).

Because the Philippines was an American territory, Filipinos were considered American nationals. As racist immigration policy took hold at the turn of the century, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese laborers were no longer coming to the United States. Hawaiian sugar plantations saw Filipinos as affordable labor and began to recruit Filipino workers. By the 1930s, more than 20,000 Filipinos had emigrated to Hawaii and more than 30,000 Filipinos re-emigrated from Hawaii to the mainland in the 1920s and 1930s after their initial labor contracts ended (Ling, 2023).

In 1934, Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, otherwise known as the Philippine Independence Act. This act began the process of Filipino independence and reclassified all Filipinos as aliens. It also established a quota of 50 Filipino immigrants per year to the United States. This loss of national status for people from the Philippines led to a significant decrease in Filipino immigration. In 1935, the Filipino Repatriation Act offered free passage for Filipinos back to the Philippines. More than 2,000 Filipinos returned to their homeland this way (Ling, 2023).

Video: Filipino Repatriation Act

Discussion Questions

- What were the primary motivations behind the enactment of the Filipino Repatriation Act of 1935? How do these motivations fit into a conversation about social justice?

- How can the Filipino Repatriation Act be evaluated in terms of its impact on the Filipino population in the United States?

- What lessons can modern policymakers learn from the Filipino Repatriation Act when designing immigration policies today?

The Contemporary Experience of Being Asian in the United States

Currently, the Asian population continues to grow in the United States. Between 2000 and 2019, Asian populations doubled, and the Pew Research Center states that by 2060, there will be more than 46 million people of Asian descent in the United States. Of these, the largest group is Chinese, followed by Indian Americans, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese. Nearly half live in the Western half of the United States, with a third living in California. Asian immigrants, in general, are younger, less likely to live in poverty, and more likely than the average United States citizen to have a bachelor’s degree (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021).

One of the ways Asian populations have immigrated to the United States is through transnational, transracial adoption. This began following the Korean War and continues today. Most adoptions come from Korea and China. However, there is also a history of adoption from other countries—particularly for children of United States servicemen in Vietnam.

Video: Adoptees Speak Out: A Mini Documentary

Discussion Questions

- What historical events or factors have contributed to the rise of Asian transnational, transracial adoption?

- How do adoptees navigate their cultural identity, and what challenges do they face in balancing their heritage with their adoptive culture?

- How can adoptive parents effectively educate themselves and their children about the adoptee’s racial and cultural background?

- How might the trends in Asian transnational, transracial adoption change in the coming years, and what factors will influence these changes?

Stereotypes and the Model Minority Myth

Since the 1960s, Asian Americans have been quite successful in the United States. Many have achieved educational, political, and occupational success. This was first noted in the press in 1966 with two articles detailing the socioeconomic achievements of Asian Americans, and this press coverage continued well into the 1980s (Ling, 2023). This success and the press response to it resulted in the stereotype of the “model minority” to describe Asian Americans. Ling states “Promoted by the popular press, the model minority image has since become a stereotype describing the socioeconomic success achieved by Asian Americans through hard work, respect for traditional values, and accommodation” (p. 181).

Ruiz et al. (2023) state that the model minority stereotype characterizes Asian Americans as high achieving, deferential to authority, intelligent, economically successful, and good at math and science. That said, many Asian people living in the United States do not identify or align with these characteristics, and many find this myth to impact both mental health and academic performance. Of the Asian Americans surveyed by Ruiz et al., only 44% of those surveyed had heard of the term “model minority” (p. 2). However, 63% stated that they have experienced someone thinking they were good at math or science in their day-to-day life. Many expressed that the stereotype has been harmful. Reasons include social pressure to succeed, all Asians being lumped into a monolithic culture, and stereotyping in the school environment.

The model minority stereotype also impacts other marginalized communities. This stereotype surfaced during the civil rights movement in direct contrast to Black and Latinx individuals fighting for equality (Ruiz et al., 2023). Often, the story of Asian American success in the United States is used to contrast the lack of success in Latinx and Black people in the United States, thus pitting different racial groups against each other (Ling, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2023). Ling (2023) states “The model minority theory has proven to be a useful and effective tool to triangulate race politics in America” (p. 182).

Video: Why Do We Call Asian Americans the Model Minority?

Discussion Questions

- In what ways has the “model minority” stereotype positively and negatively affected Asian American individuals and communities? How does the stereotype mask the diversity within the Asian American community?

- How is the “model minority” stereotype perpetuated in modern media and popular culture?

- What steps can be taken to challenge and dismantle the “model minority” stereotype in society today?

While seen as a model minority, Asian Americans also experience significant discrimination in the United States. Ruiz et al. (2023) state that 57% of Asian adults say discrimination is a major problem, and 33% say it is a minor problem. Examples of discrimination include offensive name-calling, suspicion of dishonesty, housing discrimination, workplace discrimination, and intimidation. In addition, participants discussed being bullied and harassed. Indian and Muslim Asians also report racial profiling regarding terrorism both by day-to-day people and airport security. They report this racial profiling has significantly increased since the September 11th terrorist attacks (Ruiz et al., 2023).

Video: Asian Americans Share Their Experiences with Racism

Discussion Questions

- What personal experiences with racism do the individuals in the video share, and how do these stories reflect broader societal issues?

- In what ways do the experiences shared in the video connect to historical patterns of discrimination against Asian Americans?

- Based on the video’s discussions, what actions can society take to create a more inclusive and equitable environment for Asian Americans?

The COVID-19 Pandemic

Asian Americans were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in a multitude of ways. One survey found that 51% of Chinese restaurants closed due to the pandemic, a significantly higher percentage than other types of restaurants. Much of this has been attributed to stereotypes about Chinese Americans and the origin of the COVID-19 virus (Ling, 2023). According to federal statistics, there has been a spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, peaking in 2021 (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2023). Ling states “On February 9, 2021, Stop AAPI Hate reported over 2,808 cases of hate crimes against Asian Americans from March 19 to December 2020 in forty-seven states and Washington, D.C.” (p. 243). Incidents included bullying, shunning, physical assault, spitting, and using terminology such as the “Chinese Virus” or “Wuhan Flu” to describe COVID-19 (Ling, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2023). In addition, Asian Americans reported being targeted because they were perceived as Chinese, even if they were not (Ruiz et al., 2023).

Video: Asian American community battles surge in hate crimes stirred from COVID-19

Discussion Questions

- How have Asian hate crimes affected the lives of Asian American individuals?

- How has media coverage influenced public perception and awareness of the hate crimes against Asian Americans?

- How has rhetoric from public figures and leaders impacted the increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans?

- What historical parallels exist for the discrimination faced by Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Being Indigenous in the United States

Acknowledging the complex history of the Indigenous peoples of North America can help us fully understand the history of the United States. Indigenous peoples have rich, independent histories that predate colonization and the formation of the United States. Despite this, Indigenous people are often reduced to “one-dimensional stock figures, their complexity and differences pressed flat for dramatic purposes” (Hämäläinen, 2022, p. xi). While many lump Indigenous people into one homogeneous group, there are actually 574 federally recognized, distinct tribes. The United States is home to a little over four million people who identify as American Indian (AI) or Alaska Native (AN) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023a, 2023b).

The attempted genocide of the Indigenous people of North America is one of the most shameful chapters in United States history. “America did not conquer the West through superior technology, nor did it demonstrate the advantages of democracy. America ‘won’ the West by blood, brutality, and terror” (Treuer, 2019, p. 94). That said, portraying Indigenous history solely as one of loss undermines the resilience and agency of Indigenous peoples (Blackhawk, 2023). Despite the United States government’s attempts at genocide, Indigenous communities not only survived but continue to thrive and resist today. This section aims to intertwine aspects of Indigenous histories with key moments in United States history, providing a more nuanced understanding of both through a social justice lens.

The United Nations (1951) has defined genocide as:

…any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious groups, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. (Article II)

Discussion Questions

- What are the key criteria for determining if an act qualifies as genocide? How do historical events involving Indigenous peoples align with these criteria?

- What are the arguments for and against using the term “genocide” to describe the treatment of Indigenous populations in the United States?

- How does recognizing the treatment of Indigenous populations as genocide affect contemporary Indigenous rights and sovereignty movements? What role does this recognition play in ongoing efforts to address historical injustices?

Initial Contact between Colonists and Indigenous Peoples of North America

Initial contact between Indigenous people of the Americas and European colonists occurred in the Caribbean Islands in 1492, where Christopher Columbus and 88 other people encountered the Taino. The Taino welcomed Columbus and his men with gifts and food. However, Columbus and his men sought gold, silk, and spices, not kinship. This initial meeting started the colonization of the Caribbean and, in time, the Americas. In the 1400s and 1500s, Spain dominated the Caribbean. Spanish colonists exploited Indigenous goods and people, often brutally (Hämäläinen, 2022).

From the Caribbean Islands, Spanish colonists continued north, and in the 1500s, they arrived in Florida to a coordinated and successful resistance. They also moved into what is the modern-day Southwest region of the United States from Central and South America. Again, they were met with effective resistance. By the late 16th century, the Spanish continued to be unsuccessful in colonizing North America, and the continent remained primarily Indigenous (Hämäläinen, 2022).

Colonization of the East Coast

In the 1500s, many European traders regularly arrived along the East Coast of what is now the United States and Canada to fish and trade. Occasionally, they would come ashore and attempt to establish colonies. However, the Indigenous population was often not receptive to this, preferring to keep the Europeans at arm’s length. Skirmishes between the French and Spanish colonists in Florida started to manifest over land disputes, even though none seemed to be able to colonize the Indigenous space successfully (Hämäläinen, 2022).

In 1607, three ships anchored off the coast of what is now Virginia. One hundred men came ashore and built a fort in what is now considered to be the first permanent English settlement in North America. They called their settlement Jamestown. The colonists at Jamestown had a tumultuous relationship with the Indigenous people of the area. The local Indigenous leaders tried to incorporate the colonists into their vast empire but were met with brutal resistance (Hämäläinen, 2022).

In addition to losing lives in conflict with Indigenous people, the colonists suffered from malaria, starvation, and the elements. By 1615, tobacco began to be exported from Virginia. Tobacco was widely popular in England, and the colonies’ economic value began to grow. In 1619, the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia, and tobacco production surged (Hämäläinen, 2022).

During the 1600s and 1700s, interactions between Indigenous populations and European colonists remained complex. Conflicts with the colonists and the diseases they brought with them affected Indigenous populations’ demographics. Additionally, Indigenous populations participated in trade and formed alliances with European colonies, resulting in frequent cultural clashes and conflicts (Hämäläinen, 2022).

The Revolutionary War

At first, Indigenous populations opted to remain neutral in the conflicts between the colonists and England, perceiving their conflict as infighting between a king and his subjects. However, as tensions increased and the war began, indigenous populations took sides (Makos, 2021). Many took the side of the British in hopes that it would send colonists back to England (Hämäläinen, 2022). For example,

The Cherokee nation was split between a faction that supported the colonists and another that sided with Britain. The Iroquois Confederacy, an alliance of six Native American nations in New York, was divided by the Revolutionary War. Two of the nations, the Oneida and Tuscarora, chose to side with the Americans while the other nations, including the Mohawk, fought with the British. Hundreds of years of peaceful coexistence and cooperation between the Six Nations came to an end, as warriors from the different nations fought one another on Revolutionary War battlefields. (Makos, 2021, para. 4)

After the Revolutionary War, the British gave the new United States all British territory located east of the Mississippi and south of Canada. This decision did not elicit the input of the Indigenous tribes who had fought on their side and lived on those lands. As Westward expansion began, many Indigenous populations faced White—and often brutal—colonists who believed all Indigenous people had sided with the British coming into their territories. When Indigenous people resisted or fought back, they found no support from their supposed allies in England (Makos, 2021).

While numerous conflicts occurred between Indigenous populations and colonists — and later the United States government — specific battles and wars are particularly noteworthy due to their significant impact on history and their profound effects on Indigenous communities. Below, find a brief overview of some of those early conflicts.

Battle of Horseshoe Bend: In 1814, Andrew Jackson led a group of United States soldiers and a group of Cherokee soldiers in a war known as the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the Creeks (Cowie, 2022). The battle resulted in the Creek Nation surrendering more than 20 million acres of land to the United States government (Lepore, 2018).

United States and Dakota War: In 1862, the Dakota nation, already removed from their sacred lands and placed onto a reservation, were tired of the continued encroachment and abuse of White settlers. Some of the Dakota people were starving, and the local Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agent, Andrew Myrick, refused to sell them food on credit (Hämäläinen, 2019). Additionally, the Dakota nation was angry that the BIA “failed to investigate charges of…mistreatment of Indian women by white men” (Deer, 2015, p. 33). In retaliation, “Dakota warriors killed hundreds of settlers, burned farms, raided stores, and took hostages” (Hämäläinen, 2019, p. 254).

The United States military captured approximately 2,000 Dakota people, including women and children, and held them as prisoners of war (Hämäläinen, 2019). Initially, 303 Dakota warriors were sentenced to death. However, President Lincoln intervened. Lincoln reported he would only authorize the death of those Dakota warriors guilty of rape or “perpetrating massacres” (Hämäläinen, 2019, p. 254). On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota warriors were executed by hanging. “It was and remains the largest mass execution in American history and is a source of enduring trauma for Dakota people” (Hämäläinen, 2019, p. 254).

Sand Creek Massacre: In 1864, Colonel Chivington led the First Colorado Infantry Regiment of Volunteers and the Third Regiment of Colorado Cavalry Volunteers who murdered approximately 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho people. Chivington and his volunteer forces

killed and scalped pregnant women and cut one of them open, ripped out the fetus and scalped it. They had destroyed bodies, cutting out arms, legs, fingers, noses, breasts, genitals, and hearts, decorating their hats and uniforms with pieces of humans. (Hämäläinen, 2019, p. 264)

Wounded Knee Massacre: In 1890, one of the most infamous massacres on United States soil occurred in South Dakota (Richardson, 2010). On December 29, 1890, the Cavalry Regiment, led by Colonel James W. Forsyth, surrounded a group of Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee Creek. The soldiers demanded that the Lakota surrender their weapons. While disarming the Indigenous people, a shot was fired by an unknown party, and violence erupted. The cavalry opened fire on the unarmed Lakota people, including women and children. Estimates are that somewhere between 150 and 300 Lakota people were killed. The Wounded Knee Massacre is often cited as an example of the extreme violence and injustices experienced by Indigenous peoples in the United States. It signified the outcome of oppressive measures against Native American tribes and the tragic ramifications of policies of displacement and cultural suppression (Klein, 2023).

Discussion Questions

- What common factors contributed to the conflicts represented by the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Dakota War, the Sand Creek Massacre, and the Wounded Knee Massacre? How did issues such as land, resources, and treaty violations drive these events?

- How did each of these events impact the Indigenous communities involved, both immediately following the conflicts and in the longer term? What were the specific repercussions for the Creek Nation, Dakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Sioux?

- How have historical interpretations of these events evolved over time? What are the challenges in reconciling different perspectives on these conflicts?

- How are these events interconnected in the broader history of the expansion of the United States and Indigenous resistance? How do they collectively contribute to the understanding of the history of Indigenous relations with the United States?

- How do these events continue to influence discussions about Indigenous rights, historical injustices, and the policies of the United States? What lessons can be drawn from these events for contemporary issues facing Indigenous peoples?

Reservation Era

The United States government had various justifications for its genocidal campaign against Indigenous nations. However, the primary reason was greed. Indigenous nations occupied the land that the United States wanted for westward expansion. Two specific governmental policies ensured that the United States would take possession of Indigenous lands. These were the Doctrine of Discovery and the establishment of reservations (Blackhawk, 2023).

Doctrine of Discovery – Part 1

Pope Alexander VI issued the Doctrine of Discovery on May 4, 1492, for the Catholic Church. It stated that any land not inhabited by Christians was available for discovery and claim. The Doctrine of Discovery was intended to overthrow pagan nations and spread Christianity worldwide. In 1823, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Johnson v. M’Intosh that the discovery doctrine gave the United States the right to own the land on which Indigenous people lived (Charles & Rah, 2019). The case arose from a land dispute in which Thomas Johnson bought land from the Piankeshaw Nation, and William M’Intosh claimed the same land through a United States governmental grant. Johnson v. M’Intosh established the rights of Indigenous tribes to live on their lands, but not to sell or transfer land without the approval of the United States Government (Blackhawk, 2023).

- In what ways did the Doctrine of Discovery dehumanize Indigenous populations and justify their subjugation?

- How did the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823) perpetuate the principles of the Doctrine of Discovery?

- What were the immediate and long-term effects of the Doctrine of Discovery on Indigenous communities in North America?

- How did the Johnson v. M’Intosh ruling affect Indigenous land rights and sovereignty?

- Why is it important to critically examine and understand historical doctrines like the Doctrine of Discovery in the context of social justice?

- How can acknowledging the impacts of such doctrines contribute to reconciliation and justice for Indigenous peoples?

In 1823, President James Monroe stated in his annual speech to Congress that the Western Hemisphere was off-limits to further European colonization. This declaration later became known as the Monroe Doctrine. Monroe declared that the United States would not tolerate interference from any European nation and that any interference would be seen as a sign of aggression toward the United States. This also meant that Indigenous nations could no longer rely on their European allies against the United States (Blackhawk, 2023).

By the late 1820s, many White Americans, especially in the South, viewed Indigenous nations as “simply in the way” (Blackhawk, 2023, p. 186) of westward expansion and Southern states needed Indigenous land to continue expanding cotton production. The United States government saw the Indigenous populations as a problem and sought a solution. That solution was to remove Indigenous people from their land and establish reservations (Hämäläinen, 2019).

Indian Removal Act

In the 1820s and 1830s, Georgia passed a series of legislation aimed at the Cherokee Nation. These laws invalidated Cherokee law, took Cherokee land, banned Cherokee people from testifying in court against White people, and banned Cherokee people from meeting in groups (Brown, 2022). In response, the Cherokee Nation appealed to the federal government for protection.

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia

In 1831, in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed Indigenous tribes were, in fact, nations. However, according to Chief Justice Marshall, they were not foreign nations but “domestic dependent” nations (Mays, 2021, p. 95).

In 1832, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Court ruled that Georgia’s laws had no authority within Cherokee territory, affirming the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation and recognizing their right to self-governance (Mays, 2021).

Video: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

Video: Worcester v. Georgia

Discussion Questions

- How did the Supreme Court’s ruling in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia impact the legal status of Native American tribes in relation to state and federal governments? What did Justice John Marshall mean by describing tribes as “domestic dependent nations?”

- How does the lack of enforcement of the Worcester v. Georgia decision illustrate the challenges of implementing Supreme Court rulings? What does this case reveal about the limits of judicial authority in the face of political pressures?

- In what ways did the rulings in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia influence subsequent legal and political developments regarding Native American rights and state-federal relations? How did this case set a precedent for future Supreme Court decisions?

Instead of protection, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The Indian Removal Act authorized the relocation of Indigenous tribes from their current land to land further west in current-day Oklahoma. The federal government claimed the power to exchange Indigenous land east of the Mississippi for land in the West. While the Indian Removal Act authorized negotiations and voluntary relocation, relocation was often achieved through coercion, deception, and force (Kiel, 2017). The Indian Removal Act proved to be a “brutal, sustained campaign of ethnic cleansing executed by often corrupt and inept patronage government employees” (Hämäläinen, 2019, p. 210) and had long standing consequences for multiple Indigenous tribes. In the years between 1830 and 1850, “more than 125,000 Indians…were forcibly removed to territory west of the Mississippi, mostly on foot and in wintertime. At least 3,500 Creek and 5,000 Cherokee and many from other tribes died along the way” (Treuer, 2019, p. 35).

Video: What Life On the Trail of Tears Was Like

Reading: Two Accounts of the Trail of Tears: Wahnenauhi and Private John G. Burnett

Discussion Questions

- What were the immediate and long-term effects of the Trail of Tears on the Cherokee Nation? How did the forced relocation affect the tribe’s social structure, culture, and economy?

- What do personal accounts or testimonies from individuals who experienced the Trail of Tears reveal about the human impact of the forced relocation? Why are these stories important?

- How does the Trail of Tears compare to other instances of forced migration in history? What similarities and differences can be observed in terms of causes, processes, and consequences?

- How do the events of the Trail of Tears continue to influence contemporary Native American policy and relations between tribal nations and the U.S. government?

Post Civil War

Between the Civil War and constant fighting with Indigenous tribes, the cost for the United States government to continue “an extended campaign of genocide” (Native American Rights Fund [NARF], 2019, p. 6) against Indigenous populations was no longer feasible. The United States had already spent over $750 million on war since 1840 (Hämäläinen, 2019). In addition, Americans were tired of war, both with each other and Indigenous tribes.

By the late 1800s, the sentiment of the American public shifted from fear and hatred to sympathy for Indigenous people. Even members of the United States military struggled with continued physical aggression towards a seemingly defeated Indigenous population (Cozzens, 2016). General George Cook stated:

when Indians see their wives and children starving and their last source of supplies cut off, they go to war. And then we are sent out there to kill them. It is an outrage. All tribes tell the same story. They are surrounded on all sides, the game is destroyed or driven away, they are left to starve, and there remains one thing for them to do-fight while they can. Our treatment of the Indian is an outrage (Cozzens, 2016, p. 7).

Although the United States government’s ultimate objective to acquire Indigenous lands remained unchanged, its strategy evolved. According to Hämäläinen (2019), this shift represented an attempt by the federal government to adopt a more refined approach to imperialism. Rather than resorting to violence and conflict, it aimed to manage and reshape Indigenous peoples (Adams, 2020).

President Ulysses S. Grant recognized the failures of previous policies around Indigenous tribes and introduced a new strategy known as the Peace Policy. This initiative, which spanned the late 1860s and early 1870s, aimed to reform relations with Indigenous communities and address the shortcomings of earlier approaches. Grant’s approach aimed to shift from aggressive expansion to a more humane interaction with Indigenous populations. In addition, the policy included an intentional effort to assimilate Indigenous populations into mainstream American culture. As part of this, indigenous agents would be appointed to the BIA. Grant appointed Ely S. Parker of the Seneca Nation to head the BIA. He served from 1869-1871 and advocated for Indigenous rights (National Park Service, n.d.).

After the Civil War ended, White nationalism was at an all-time high and westward expansion in the United States continued. While the Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia had established that Indigenous nations were sovereign, many in the United States felt that Indigenous people were now, with the advent of reservations, reliant on the United States government and should no longer be sovereign. In 1871, the Indian Appropriations Act was passed with a rider, which invalidated Indigenous sovereignty. Thus, the United States government would not negotiate further treaties with Indigenous tribes. The Indian Appropriations Act also gave the United States Congress more power to establish policies regarding Indigenous people. “This new phase of federal Indian policy was known as assimilation, and as bad as the years of warfare and treaty making had been, assimilation would be immeasurably worse” (Treuer, 2019, p. 114). The new policies were built upon three fundamental pillars: Christianization, education, and the promotion of private property (Grinde, 2004).

Christianization

The American public’s sentiment shift was partly influenced by the rise of social reform movements in the United States. During the 1880s, “a chorus of voices from the pulpit, press, and Congress were again calling for a major overhaul of Indian policy” (Adams, 2020, p. 10). Social reform organizations, such as the Women’s National Indian Association (WNIA) and the Indian Rights Association (IRA), focused on the plight of the Indigenous people. According to these social reformers, the only way to save the Indigenous people was to civilize them through Christianization (Adams, 2020).

Education

Education was a vital component of the United States government’s assimilation strategy (Adams, 2020). The Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz, “estimated it cost nearly a million dollars to kill an Indian in warfare, whereas it cost only $1,200 to give an Indian child eight years of schooling” (Adams, 2020, p. 23). Education made economic sense and complied with the federal government’s needs.

During the 1800s, the common school movement increased Americans’ appreciation for education (Adams, 2020). Social reformers, such as Horace Mann, believed government-supported education created “a more useful citizen in the community” (Vinovskis, 1970, p. 562). Many social reformers viewed education “as a seedbed of republican virtues and democratic freedoms, a promulgator of individual opportunity and national prosperity, and an instrument for social progress and harmony” (Adams, 2020, p. 21). Therefore, social reformers believed that education was the most efficient route to civilizing Indigenous people, specifically Indigenous children. Three education models were employed in attempts to assimilate Indigenous children. These were the reservation day school, the reservation boarding school, and the off-reservation boarding school (Adams, 2020).

Video: Who Were the Common School Reformers?: A Short History of Education

Video: The Origins of the American Public Education System

Discussion Questions

- How did the common school reforms and the origins of the public school system influence Indigenous populations in the United States? Consider both the direct and indirect consequences.

- How did the goals of the United States public education system align or conflict with Indigenous cultural values and education systems?

- In what ways did the history of public schooling in the United States contribute to the assimilation policies that targeted Indigenous populations? Discuss the implications for cultural preservation.

Reservation Day School Model

The first educational model used to assimilate Indigenous children was the reservation day school. Initially popular, 48 reservation day schools were in operation in the United States by the 1860s. Typically located near or on Indigenous reservations, reservation day schools allowed Indigenous children to arrive in the early morning and go home to their families at the end of the day. The reservation day schools provided elementary-level education and focused on English language instruction and vocational training (Adams, 2020). Additionally, “the day school curriculum also provided for lighter activities such as singing and calisthenics, the former offering a perfect opportunity to introduce the Christian message in the form of hymns” (Adams, 2020, p. 33).

Some of the advantages of the reservation day school model were that the schools were inexpensive to operate and that Indigenous parents were less resistant to them. In addition, social reformers hoped that Indigenous children would bring what they learned home to their parents (Adams, 2020). However, this was not the case. The reservation day school model was eventually deemed an ineffective “instrument of assimilation” (Adams, 2020, p. 34).

Reservation Boarding School Model

The failure of the reservation day school model led to the idea that “sustained confinement was…the key element in the civilization process” (Adams, 2020, p. 36). As part of President Grant’s Peace Policy in 1869, boarding school policies were implemented as a model to assimilate Indigenous children (NARF, 2019). The Boarding School Policy “authorized the voluntary and coerced removal of Native American children from their families for placement in boarding schools run by the government and Christian missionaries” (NARF, 2019, p. 7). By the late 1870s, with the reinforcement of the Boarding School Policy, the reservation day school model was replaced by the reservation boarding school model (Adams, 2020).

Reservation boarding schools were typically located near BIA offices on the reservation and were under the domain of the local BIA agents. Reservation boarding schools included four elementary grades and four advanced grades. Like the reservation day schools, the curriculum at the reservation boarding schools focused on instruction in the English language and vocational training. Indigenous children were required to remain at school for nine months a year and only allowed to visit their families during summer vacations. For government officials and social reformers, the primary advantage of the reservation boarding school model was the increased control over Indigenous children’s lives (Adams, 2020).

BIA agents, government officials, and social reformers expressed concern that reservation boarding schools allowed Indigenous children too much access to their culture due to the schools’ proximity to Indigenous reservations (Adams, 2020). BIA agents were frustrated that when Indigenous children went home for the summer, they reverted to their “savage mode of life” (Adams, 2020, p. 37). NARF (2019) points out that “mere education was not enough…Separating children from their family, their tribe, their culture, and their homes on the reservations was necessary to [sic] larger goal of assimilating them into the majority culture” (p. 6). BIA agents, government officials, and social reformers concluded that the only path to complete assimilation of Indigenous children was to remove all influence of their cultures. This conclusion led to the rise of the third educational model, the off-reservation boarding school (Adams, 2020).

Off-Reservation Boarding School Model

The first off-reservation boarding school, the Carlisle Indian School (Carlisle), was founded in 1879 by Captain Richard Pratt (Adams, 2020; Treuer, 2019). Pratt’s military style of education became the model for Indigenous education across the United States (Treuer, 2019). “In fact, for several years philanthropists looked upon Pratt as a sort of Moses for the Indians” (Adams, 2020, p. 60). Pratt’s success at Carlisle proved that the off-reservation boarding school model solved the United States government’s Indian problem. By 1894, approximately 100 off-reservation boarding schools existed in the United States (Treuer, 2019). Unfortunately, not all boarding schools were the same. Carlisle “under Pratt’s supervision and congressional scrutiny…was better staffed and better run than others around the country, which seem hellish in comparison” (Treuer, 2019, p. 137).

Although Pratt believed Indigenous people were “capable in all respects as we are, and that he only needs the opportunities and privileges which we possess to enable him to assert his humanity and manhood” (Treuer, 2019, p. 134), he also believed that they were culturally inferior to White Americans. Pratt’s educational philosophy was based on his famous phrase, “Kill the Indian in him and save the man” (Adams, 2020, p. 56). Pratt believed, like so many other White Americans, that cultural erasure was the only way for Indigenous people to assimilate into society (Adams, 2020; Treuer, 2019).

Cultural Erasure

The boarding school model was designed to erase all traces of Indigenous identity from Indigenous children (Adams, 2020). “From the policymakers’ point of view, the civilization process required a twofold assault on Indian children’s identity” (Adams, 2020, p. 109). The first identity assault was the removal of any outward Indigenous cultural markers. The second identity assault was instruction on how to assimilate into White American culture. Pratt believed that complete immersion into White American culture would transform Indigenous children. According to Pratt, “We make our greatest mistake in feeding our civilization to the Indians instead of feeding the Indians to our civilization” (Adams, 2020, p. 57).

The United States government used a multitude of strategies for its campaign of cultural genocide of the Indigenous people of North America. Assimilation required that Indigenous people change everything about their identities and their cultures. Carasik and Bachman (2019) define cultural genocide as:

any attempt to destroy a group as such by eliminating the group’s culture. Acts that constitute cultural genocide include criminalization or de facto prohibition of a group’s language, religious practices, customs, and traditions; destruction of heritage sites, artifacts, artwork, historical records, and books; and indoctrination and forced assimilation of a group’s children into another group. (p. 98)

Discussion Questions

- How have government policies aimed at assimilating Indigenous peoples—such as residential schools, land allotment, and anti-cultural legislation—contributed to the erosion of Indigenous cultures? What were the intended and unintended consequences of these policies?

- How do contemporary assimilation policies and practices affect current Indigenous cultures? Are there current examples of assimilation or cultural erosion, and how are Indigenous communities responding to these challenges today?

- What are some potential strategies for preventing cultural genocide and supporting the cultural sovereignty of Indigenous peoples moving forward? How can policies be reformed to ensure the protection and flourishing of Indigenous cultures?