5 Legislation and Policy

Bernadet DeJonge; Nikki Golden; and Cailyn F. Green

- The reader will understand the history of discriminatory laws and policies in the United States.

- The reader will analyze how legislation and policy impact current socioeconomic trends for communities of color.

- The reader will describe how discriminatory legislation and policy continue to reinforce the stereotyping of marginalized populations.

Many scholars have stated that social change occurs at the intersection of personal behavior change and policy change. That said, policy is often cited as having more influence on social change than personal activism (Hébert-Dufrense et al., 2022). There have been ongoing perspective shifts in understanding racism and marginalization. With this, discussions of social justice now focus on systemic issues of power, privilege, and oppression.

Systems of power have existed since the first settlers arrived in the United States and continue to exist today. Throughout the complex history of the United States, division around religion, slavery, race, immigration, gender, sexual orientation, and colonization has been cemented in discriminatory law and policy. While it is important to understand history, it is also important to be aware of how the complicated past of discriminatory laws has resulted in lasting consequences. This chapter examines these discriminatory laws and policies and outlines the long-term effects they have had on marginalized communities in the United States.

Imagine two runners running a race against one another. Each is equally fast, but the first runner is given a mile head start. Because of this advantage, the second runner will never be able to catch up even though they have equal skill. This is systemic racism in a world where racial equality, not equity, has been achieved.

Now imagine that the second runner, who is already a mile behind the first, must periodically jump over hurdles. These hurdles slow them down even further. Those hurdles are the many issues described in this chapter that disproportionately impact people of color. In the end, that second runner will never be able to catch up.

Discussion Questions

- How does the running analogy fit into your current understanding of racism?

- What does the analogy teach us about the historical and generational impacts of racism?

- How do we create a scenario where the second runner catches up?

Historical Laws and Policy

The United States has a history of racist laws and policies that continue to impact people of color today (Best & Meja, 2022; Rothstein, 2017; Yearby et al., 2022). Slavery was, clearly, one of the first. However, even after the end of slavery, Jim Crow laws continued to enforce segregation in the United States, particularly in the southern states. Jim Crow laws, based on the legal doctrine of “separate but equal,” segregated Black Americans in the United States for decades (PBS, n.d.). Some examples of Jim Crow laws include illegal interracial marriage, division in transportation systems, burial segregation, and segregation of sports teams. Other examples of discriminatory laws in the 19th and 20th centuries included the Page Act of 1875, The Chinese Exclusion Act, and The Dawes Act (Bowling Green State University, n.d.).

After World War II, Jim Crow laws were challenged by the civil rights movement. In 1948, the United States military was racially integrated by President Harry S. Truman, and in 1954, the famous Brown v. Board of Education case ended racial segregation in schools (History.com, 2023). Ten years later, in 1964, the Civil Rights Act marked the legal end of Jim Crow laws. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 followed. Despite these legal wins, some argue that, in the United States, laws and policies continue to be racist and separatist, particularly in southern states (History.com, 2023).

Video: Plessy v. Ferguson and Segregation: Crash Course Black American History #21

Learning Link: The Enforcement Act of 1870 (1870-1871)

Discussion Questions

- How did court cases like Plessy v. Ferguson and policies like the Enforcement Act contribute to systemic racism in the United States?

- What did the Enforcement Act mean for Black people in America? How does the Act impact Black Americans today?

- Why is it relevant that the Enforcement Act was taken to the Supreme Court and dismissed as a states’ rights issue? What did this mean for Black Americans at the time? What does it mean for Black Americans today?

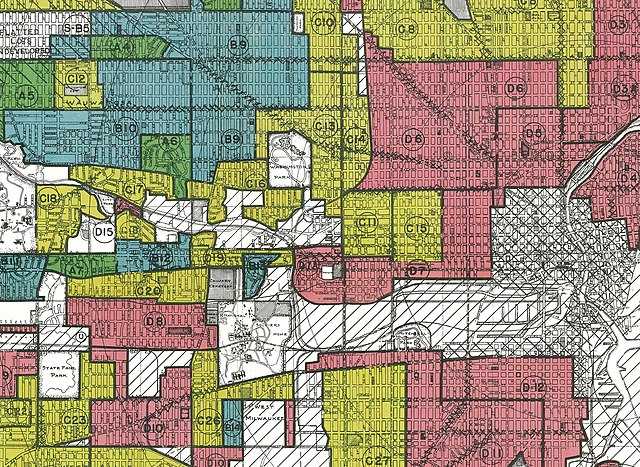

Redlining

The term redlining stems from the 1930s, post-Depression era when the New Deal Legislation was introduced in the United States. One of the New Deal provisions offered government-insured mortgages intended to stop people in the United States from losing their homes. As these mortgage programs grew into the mortgage industry, policies about who was eligible for mortgage loans were developed. Eligibility practices included property risk ratings. If someone lived in a high-risk neighborhood, they were not eligible for government-insured loans. People of color, who were often poor, often lived in neighborhoods that were rated high risk. Color-coded maps ranked neighborhoods, and houses that fell within a red area were deemed ineligible for government-insured mortgages. This practice is now referred to as redlining (Jackson, 2021).

Redlining maps were government-issued, but private lenders used them as well. Because of redlining practices, home values in numerous Black neighborhoods plummeted. Many potential homeowners, who were people of color and lived in the redlined districts, could not secure funding for a home. Those who did were given high-interest loans, which were virtually impossible to pay off (Rothstein, 2017). During this time, housing prices were at a premium and many Black families could only afford substandard and crowded housing. This housing was the foundation for what is often referred to as ghetto housing projects (Rothstein, 2017).

In 1976, historian Kenneth T. Jackson discovered one of the color-coded maps when searching other housing records, and this was the first time that the official government practice of redlining came to public light (Jackson, 2021).

Website: Mapping Inequality: Redlining in the New Deal America

Discussion Questions

- Do you think Kenneth T. Jackson understood what he had found when he found the redline maps? Why or why not?

- Explore the mapping inequality website. What did redlining look like in the community where you live? How does that continue to impact the community you live in today?

Video: Redlining and Racial Covenants: Jim Crow of the North

Discussion Questions

- How was redlining associated with Jim Crow legislation and policy?

- How does Jim Crow legislation and policy impact people of color in the United States today?

- How does redlining impact people of color in the United States today?

- How do Jim Crow legislation and redlining connect to each other?

In 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Civil Rights Act was passed. One of the bills included was the Fair Housing Act, which outlawed discrimination in housing and ended the formal practice of redlining (Jackson, 2021). However, despite the Fair Housing Act, racist practices have continued to be rampant in the housing industry. Best and Mejia (2022) reviewed 138 cities that had redlining maps and found that, overwhelmingly, neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s continue to be primarily Black, Latinx, or Asian, while neighborhoods that were greenlined (deemed worthy of lending) are still predominantly White.

Redlining practices had a significant impact on a Black family’s ability to accumulate wealth. Policies such as redlining have contributed significantly to the statistical wage and wealth gaps commonly seen between races in the United States.

The legacy of redlining extends far beyond housing segregation, too. Its impact can be seen today in minority neighborhoods’ access to health care, poorer educational opportunities, and increased risk of climate change, as many of these areas are more prone to flooding and extreme heat. Without a serious confrontation of its lasting generational damage, the racial segregation caused by redlining isn’t going anywhere either. (Best & Mejia, 2022, para. 48)

I (Dr. DeJonge) moved to Syracuse in 2021 from the Seattle area. I was referred to a realtor who I enjoyed working with. I really wanted to be in the more urban center of the city, but he kept steering me away toward the suburbs. I remember feeling a bit uncomfortable with it. It felt wrong somehow. As housing was a challenge to find, I did end up in the suburbs. Now that I am establishing a community here, I hear a lot about how lucky I was to have a good realtor who steered me in the “right” direction. I hear a lot about how there is a lot of crime in certain areas and a lot of racism that is masked as “safety” and “property values.”

Discussion Questions

- Is what my realtor did illegal? Why or why not? Is it ok to steer someone to more affluent areas when they are buying a home?

- What kinds of things might impact a realtor steering people to predominantly White neighborhoods?

- Is what my local friends tell me about being lucky true? Are they redlining? If yes, how?

- How do we balance out home values, safety, and other factors when looking at housing and historically redlined areas? What can we do to combat this segregation in the housing market?

In examining the long-term impacts of redlining and housing discrimination, two phenomena permeate the literature (Best & Mejia, 2022). The first phenomenon is the concept of White flight. White flight refers to White people moving from urban to suburban areas in response to people of color moving into previously White neighborhoods. Best and Mejia cited the city of Detroit as an example of White flight.

The second phenomenon is gentrification. As White people move into formerly redlined areas, property values increase and lower-income people, many of whom are people of color, cannot afford to stay. Gentrification is the direct result of federal tax reform intended to infuse the inner-city areas with money. Federal tax breaks, taken advantage of by White people who had the financial capacity to restore historic areas, led to low-income families of color having to leave their homes. An example of this phenomenon is the inner-city areas of Philadelphia (Best & Mejia, 2022).

As homeownership is the most common form of wealth accumulation in the United States, policies such as these increase the wealth gap between White people and people of color. According to Best and Mejia (2022),

simply encouraging homeownership…where the housing stock is old and dilapidated, could saddle Black Americans with debt. Without being able to fund repairs or escape long, predatory mortgages, these programs could exacerbate the housing crisis and push more Black people out of their neighborhoods. (para. 45)

Discussion Questions

- How have policy and legislation impacted communities of color?

- Talk about White flight and gentrification—how can we impact these behaviors?

- Do we still “redline?” How?

United States Tax Structures

Another set of policies that impact wealth equity in the United States are tax structures. Although, in general, federal income tax is a progressive tax structure, meaning people pay more if they earn more, state tax structures, such as consumption taxes, disproportionately impact low-income communities of color. The impact of these taxes varies from state to state, and less progressive states often have more inequitable tax structures. According to Davis, Hill, and Wiehe (2021), sales and excise taxes (often referred to as consumption taxes) impact wealth equality the most because low and middle-income families spend a larger percentage of their income on consumption goods compared to high-income families.

Property tax structures can also be discriminatory. Homes owned by White people in predominantly White neighborhoods continue to have higher value due to historical redlining practices. Higher home values lead to higher property taxes, which is how most public schools are funded. Thus, public schools in predominantly White neighborhoods are often better funded than those in predominately Black neighborhoods. Early advantages of attending well-funded public schools, many of which impact future wage earning, continue to disproportionately benefit White students. Think back to the running example—poorly funded public schools are one of the hurdles people of color face. This is a current, concrete example of the impact of redlining.

In some areas, assessment and property tax structures continue to be discriminatory as homes in lower-income areas are inappropriately assessed with inflated values. Thus, some Black and Latinx homeowners end up with assessment values on their homes that are significantly more than the realistic selling price. This leads to tax bills that are 10 to 13 percent higher than White homeowners who own homes with the same market value (Hill et al., 2021).

People of color earn lower wages than their White counterparts and experience poverty at higher rates due to both individual and systemic racism (Hill et al., 2021). Tax codes in the United States increase this wealth gap by disproportionately taxing consumer goods, which are consumed more by people of lower income. While these issues are complex and nuanced, it makes sense to advocate for them to be examined and remedied as issues of inequity (Infanti, 2019). “Years of racism and discrimination across all segments of society—the housing market, labor market, financial industry, education systems, criminal justice, and other areas—have prevented people of color from building wealth on the same level as white families” (Hill et al., 2021, p. 7).

Discussion Questions

- Do you think the United States tax system is fair? Why or why not?

- Do you think the United States tax system perpetuates racism? Why or why not?

- How would you propose we make the United States tax system more equitable for people of color?

Predatory Lending

Subprime Mortgages

In the early 2000s, the United States experienced a housing bubble. A housing bubble is when housing prices increase due to increased demand. Prices continue to increase until the bubble “bursts” (Investopedia, 2020, para. 1). The early to mid-2000s housing bubble was particularly severe, brought on by an economic boom in the technology sector, which subsequently crashed. When this happened, many investors moved their money into the housing market. This sudden surge in the housing market was reinforced by governmental policies to encourage homeownership, including offering exceptionally low interest rates (Investopedia, 2020).

During the housing bubble, it was easy to obtain a mortgage. If an individual or family was not eligible for a standard or prime mortgage, they were often offered subprime mortgages. Subprime mortgages generally have a higher interest or a variable interest rate that fluctuates. This is often referred to as an adjustable-rate mortgage or ARM loan (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2017). Subprime mortgages may have higher closing costs, higher interest rates when fixed, longer payment periods, or interest-only options (Akin, 2022). These subprime mortgages are often offered to individuals who do not qualify for a standard mortgage—usually people with low socioeconomic status and disproportionately people of color.

Studies show that during the housing bubble in the 2000s, predatory subprime loans were targeted towards people of color. Even when credit risk was controlled, Black people were almost four times more likely and Latinxs were almost three times more likely to receive subprime loans than their White counterparts. Compared to prime lending, people who take out subprime loans are eight times more likely to default. Thus, when the housing bubble burst and interest rates started to rise, people of color were disproportionately affected by the subsequent increase in home foreclosures as their house payments became unaffordable.

In addition, many argue that these subprime loans were offered with the intention that they would default. This is because mortgage defaults equated to profits for lenders. As housing turned over repeatedly, lenders continued to profit, while people of color lost their housing. According to Mehkeri (2014),

These mortgages were made to default. By using this fraudulent tactic, financial institutions were able to obtain big, short-term gains at the expense of homeowners. This was an exploitation of the most disempowered communities of the U.S. by the most powerful companies in finance. Despite the financial collapse of 2008, minority communities can still feel the expense of such exploitation today. (p. 1)

Foreclosure has multiple repercussions. It impacts credit scores and impacts an individual’s ability to rent or buy a home again. Finding housing with a foreclosure on a credit report is difficult (Mehkeri, 2014). Beyond personal financial repercussions, foreclosures also impact communities of color. Many communities affected by the housing bubble crash were the same communities impacted by redlining. The compounding of racial injustices has led to increased violence, decreased property values, and decreased funding for essential services in affected communities of color. It has been argued that generations will feel the effects of these racist and unjust policies for years (Mehkeri, 2014).

Discussion Questions

- How does subprime lending intersect with social justice?

- How do subprime mortgages disproportionately impact communities of color?

- Is there a place in our financial marketplace for subprime lending? Why or why not?

- Should subprime lending have more oversight/laws/policies? Why or why not? What kind of policies?

Short-Term Loans

Predatory loan lenders rely on an “information advantage” over their consumers (Cyrus, 2023, para. 6). Lenders know how to manipulate loans so that people keep coming back to borrow. In 2010, in response to the housing bubble and crash, the Dodd-Frank Act was passed by the United States Congress to address issues of predatory lending and to create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Despite the protections in place, predatory lending in Black and Latinx communities continues to be rampant, often through short-term or payday loans (Cyrus, 2023).

Many short-term loans have exceptionally high interest rates and hidden fees. They often roll over into new loans, which traps people in a cycle of debt (Cyrus, 2023). According to the St. Louis Fed, in 2019, the average interest rate on payday loans was 391%. This contrasts with 17.8% for the average credit card and 10.3% for the average personal loan from a commercial bank (Broady et al., 2021). Cyrus goes on to say: “The key components of the industry, from geography to marketing, take aim at Black and Latinx borrowers in need. Low wages, generational poverty, and a lack of traditional financial services funnel people to predatory lenders” (para. 9).

Video: Interest Rates

Video: How Expensive is Credit Card Interest?

Video: Payday Loan Interest Rates

Discussion Questions

- If Lorin has a credit card at 17.8% interest and borrows 1000 dollars for a year, how much will they pay in interest in a year?

- If Lorin has a payday loan at 391% interest and borrows 1000 dollars, and it continues to roll over for a year, how much will they pay in interest in a year?

- Which loan would you rather take out after doing the math? Why?

- Why might Lorin have to choose the payday loan instead of the credit card?

- How might the difference between these loans impact how Lorin accumulates wealth?

- How might each loan impact Lorin’s children and grandchildren in the future?

Often, payday lending, pawn shops, and check cashing centers are conveniently located in communities of color that do not have other banking options (Broady et al., 2021; Cyrus, 2023). As online banking becomes more prevalent, many brick-and-mortar banks are closing, and bank deserts are forming (Cyrus, 2023). Of the banks that closed between 2017 and 2021, a third were in minority communities, leaving many without traditional banking options (Broady et al., 2021).

High-cost lending services purport to serve communities that traditional banking leaves out. However, those services are often predatory and contribute significantly to the wealth gap between White people and people of color. Mortgages continue to be challenging to obtain both in communities of color due to historical redlining practices and for people of color due to racist practices by individual banks (Broady et al., 2021). While the CFPB was established to address predatory lending, the actual impact of this agency has been negligible (Cyrus, 2023). Thus, communities of color continue to fall prey to predatory lending practices.

Discussion Questions

- How is short-term, high interest lending an issue of social justice?

- How does predatory lending continue the racist legacy of redlining?

- What kinds of solutions are there to predatory lending practices?

- How responsible should banks and short-term lenders be in providing fair and equitable access to credit and loans? How do we reinforce their responsibility to the communities they serve?

Student Loans

Generational wealth plays a significant role in student loan statistics. Students of color often have more student loan debt. This is because they statistically start with fewer financial resources. Think back to the running example—this is the runner who starts a mile behind. For these individuals, parents and grandparents have less wealth due to historical inequities that affect wealth building. Thus, students of color acquire more debt when attempting to get ahead. The wage gap then negatively impacts student loan payments as people of color are statistically likely to earn less than their White counterparts. Because these students are not earning the same as their White counterparts, making payments on their loans is more difficult for them (Grabenstein & Khan, 2022). This is another hurdle in our running example as people of color struggle to succeed following graduation.

Statistics show that students of color have more student debt than White students and owe, on average, $25,000 more (Hanson, 2023; Perry et al., 2021). This disparity increases throughout the life of the loans due to the compounding interest (Hanson, 2023). Students of color with student loan debt are less likely to own a home, less likely to pay off their student loans, and are more likely to be behind on their student loan payments. This leads to an increased number of students of color defaulting on their student loans, which impacts credit and the ability to accumulate wealth in the future (Grabenstein & Khan, 2022).

In response to the student loan crisis, the United States government developed the income-driven repayment plan (IDR). The IDR plan allows students to make student loan payments based on their income. However, with interest on the total student loan debt continuing to accrue, the result of the IDR plan is perpetual payments towards a debt that continues to increase. Thus, many students will never be able to pay their student loan debt in full (Perry et al., 2021). This perpetual balance of student loan debt, often throughout a lifetime, contributes negatively to the mental health of students of color (Mustaffa & Davis, 2021).

Scholars have suggested that student loan debt forgiveness is a form of racial justice (Grabenstein & Khan, 2022). Mustaffa and Davis (2021) reported that student loans both perpetuate and are perpetuated by structural racism and that framing the experience of student loan debt as good debt ignores the lived experience of students of color. Perry et al. (2021) stated:

Wealth is not a direct result of hard work and determination in college. And racial wealth disparities are not a direct result of differences in college completion rates. Anti-Black policies across multiple sectors have diminished wealth-building opportunities that accelerate economic and social mobility. To ignore wealth disparities in the search for solutions to the student debt crisis is to turn a blind eye to the systemic racism that created the crisis itself. (para. 31)

Discussion Questions

- Discuss how generational wealth impacts the experience of student loans for students of color.

- Many have claimed that student loan forgiveness is a form of racial justice. Why might this be? Do you agree? Why or why not?

Healthcare Policy

Structurally racist policy has consistently impacted the implementation of social safety net programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Assumptions based on stereotypes of Black people being lazy and the “Welfare Queen” rhetoric permeates legislative discussion and policy around the funding for social safety net programs (Levin, 2019; Yearby et al., 2022). It has been argued that the 20% Medicare service co-pay was implemented to discourage access to communities of color. TikTok influencer Goddess Mia (2023) said it best: “We have to pay 20% because of racism!” (1:43). Healthcare policy decisions are grounded in White culture, with most policy decisions being made by White people (Yearby et al., 2022). These policy decisions are rife with marginalization, oppression, racism, and bias, which negatively impact communities of color.

Medicaid

As of 2023, there were 86.7 million people on Medicaid programs in the United States (Medicaid.gov, 2023). Medicaid receives funding from both federal and state budgets and is administered by the state in which an individual lives. Thus, an individual with the same income and/or situation may receive different benefits depending on which state they reside in (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020). Medicaid recipients are mainly people of color, older adults, and disabled people (Alio et al., 2022).

Research shows that, statistically, people of color are in worse health than their White counterparts. This is often attributed to social determinants of health. Social determinants of health are the environmental conditions people are born in and live in that can have an impact on their health. Examples include socioeconomic status, access to and quality of education, access to and quality of healthcare, where people live, and the social context in which people live (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Many negative social determinants of health are rooted in racism and marginalization, and can be traced back to segregation, Jim Crow Laws, and redlining (Haldar et al., 2023).

One of the compounding pieces of social determinants of health is access to Medicaid-funded services. Access to Medicaid services is often discriminatory, and Medicaid-funded patients often struggle with access to appropriate and timely medical care. Physicians are less likely to take Medicaid patients and when they do, their services are often not timely. This is even more significant with patients of color and could be considered continued structural racism in medical practice. Alio et al. (2022) suggested multiple avenues to address these inequities. These suggestions included clear policies from medical centers that outline their Medicaid acceptance policies, a commitment to addressing issues of structural racism in healthcare, and federal and state governments incentivizing Medicaid acceptance.

Video: Black Maternal Mortality in the US and its Slave Origins

Discussion Questions

- What kind of ideas do you have about how to remedy the statistics on Black maternal mortality?

- How does Black maternal health relate to the history of slavery and Black marginalization?

- The Black maternal mortality rate has been called a silent crisis—why do you think that is?

Medicare

Medicare is federally funded health insurance for people over 65 and those under 65 who are disabled. Medicare covers a portion of most healthcare services, including hospitalization, physician services, and prescription drugs. Part A is for inpatient hospitalization, Part B is for outpatient services such as doctor visits and home health, Part C is the advantage plans, which turn benefits over to a health maintenance organization (HMO), and Part D is for prescription drug coverage (KFF, 2019).

While Medicare provides insurance to older adults and disabled people, there are also coverage gaps that impact low-income recipients. For example, Medicare does not cover eyeglasses, hearing aids, dental work, in-home care, or long-term care (KFF, 2019). Medicare coverage also significantly limits substance use and mental health treatment (Medicare.gov, n.d.; Steinberg et al., 2021). As mentioned above, Medicare has a 20% co-pay for most services (Medicare.gov, n.d.). In addition, if an individual is under 65 with an approved disability, there is generally a two-year waiting period between when the disability is determined and when coverage begins, depending on the diagnosis (KFF, 2019). For example, if you have end-stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), you can receive Medicare immediately after disability status is obtained. However, if you have a condition such as paralysis from an accident or are approved based on a mental health diagnosis, there is a two-year waiting period for coverage (Srakocic, 2021).

Private Insurance

Many people in the United States obtain health insurance through employment. That said, Collins et al. (2022) found that 23% of working adults are underinsured, meaning they have insurance, but access to medical care is still not affordable. Often, these individuals are not eligible to switch to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace due to a “firewall” (Yearby et al., 2022, p. 189) in the ACA. Yearby et al. (2022) refer to a policy that prevents specific individuals from accessing ACA Marketplace subsidies if they have access to employer-sponsored health insurance. Many cannot afford this option despite it being touted as affordable.

Lower-paying jobs are disproportionately filled with Black and Brown Americans; thus, those being most impacted by inadequate healthcare coverage are those who have been traditionally marginalized in the United States. Marginalized people are left struggling to manage insurance premiums, high deductibles, and coverage limitations. In addition, the cost of medication is often prohibitive. Collins et al. (2022) found that up to a quarter of people surveyed who struggled with a chronic health condition had chosen not to fill a medication prescription in the last year due to cost.

I (Dr. DeJonge) had a conversation with a friend recently about health insurance. They told me they were going to take a year off from their health insurance and go uncovered. I was horrified by this, but for them, it is an issue of cost. They pay a large monthly premium so they and their child can be covered—and they still have a $15,000 deductible. They said they never hit their deductible, so why pay the premiums on top of their already high out-of-pocket expenses?

Discussion Questions

- What would you do as the person making this decision in this situation?

- What would you say as the friend hearing about this decision?

- Discuss the policy and personal elements of this scenario. How much is policy, and how much is personal choice?

The Uninsured

Despite the ACA and Medicaid expansion, many remain uninsured in the United States. Of those uninsured, many are people of color (Young, 2020). The uninsured population in the United States is more likely to be poor, sicker, and reside in the southern states (Collins et al., 2022). Collins et al. found that 79% of those surveyed had been without health insurance for a year or more. The main reason for the lack of healthcare is premium costs. Yearby et al. (2022) stated:

Among those who fall into the Medicaid coverage gap—people too poor to afford insurance but who do not meet the narrow eligibility categories of traditional Medicaid—about 60 percent are people of color, who disproportionately live in Southern states that choose not to expand Medicaid. Black people are more than twice as likely as White people and Latino people to fall in the coverage gap. (p. 189)

Discussion Questions

- What are your initial thoughts on this clip?

- What should we do for these first responders?

Incarceration

The United States has more people incarcerated than any other country in the world, many of whom are people of color. Discrimination in the United States justice system is rampant. It begins with the school-to-prison pipeline and continues through policing, arrest, jury selection, sentencing disparities, resources for defense, incarceration, and parole (Nembhard & Robin, 2021; Wiley, 2022). Nembhard and Robin reported that laws and policies have always been written and enforced by people in power and that the definition of what is criminal in the United States is rooted in racist practice and structural inequity. Examples of historical discriminatory policy include vagrancy laws, Jim Crow laws, labeling civil rights activists as violent, and the war on drugs (Nembhard & Robin, 2021).

Podcast Series: In the Dark: Season Two

Article: Mississippi to pay Curtis Flowers $500,000 after 23 years of wrongful imprisonment

Discussion Questions

- What discriminatory practices occurred in the Curtis Flowers case?

- How does this case tie into a discussion of incarceration and racism?

- How does local versus Supreme Court play a role in this case? How does it play a role in creating an equitable justice system?

- Is $500,000 enough money to compensate Mr. Flowers? Why or why not? How do we compensate for something like this?

School-to-Prison Pipeline

In 2012, the United States Department of Justice sued a school district in Mississippi for running a “school to prison pipeline” (Blitzman, 2021, para. 1). This lawsuit began a national conversation about the criminalization of children of color, especially Black children, in the school system. The school-to-prison pipeline is a set of school system policies that push students out of the classroom and into the justice system.

School systems have implemented policies such as zero tolerance, police presence, physical restraint, and automatic punishment (Blitzman, 2021; Elias, 2013). However, these policies have had a disproportionate impact on children of color and children with disabilities (Elias, 2013). Studies indicate that students of color are three to five times more likely to be suspended or arrested compared to White students (Blitzman, 2021).

The school-to-prison pipeline is fed from underfunded, under-resourced schools that are often in low-income districts. Students from these schools are more likely to be labeled as having behavioral issues. They are also less likely to graduate, increasing the likelihood of contact with the justice system (Blitzman, 2021). Thus, the school-to-prison pipeline is a direct result of historical racism and segregation, particularly the practice of redlining. Blitzman suggests that we are not struggling with a school-to-prison pipeline, but a “…cradle to prison pipeline” (para. 4).

Racism and the Criminal Justice System

The Sentencing Project (2018) reported that Black Americans are almost six times and Latinx Americans are about three times as likely to be arrested than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black people are twice as likely as White people to be killed by the police (Nembhard & Robin, 2021).

The above disparaging statistics begin with the school-to-prison pipeline and continue throughout the lives of marginalized people. In addition, it is relevant to note that these statistics perpetuate the stereotype that Black people are dangerous while discounting issues of systemic racism, discrimination, and bias throughout the criminal justice system (The Sentencing Project, 2018). The criminal justice system then traps low-income people into an endless cycle of debt and criminal activity. Fees accrue while behind bars, which can impact economic well-being for generations (Huang & Taylor, 2019). Roth (2022) gives an example from a 2015 Department of Justice report:

An African American woman who in 2007 was fined $151 for parking illegally. In a little more than three years’ time, the woman, who had experienced homelessness, was charged with seven offenses for failing to appear in court and missing fine payments, each offense then leading to an arrest warrant and additional fees and fines. Over a period of seven years—for the same parking offense—the woman was arrested twice, spent six days in jail, and paid $550 to the court. Despite initially owing a $151 fine and already paying $550, the woman still owed $541 when the Department of Justice report was written. (para. 1)

Discussion Questions

- How is the school-to-prison pipeline racist?

- What alternatives are there to zero-tolerance policies in schools?

- What are the disadvantages to changing zero-tolerance policies in schools?

- How does the school-to-prison pipeline and, later, the criminal justice system perpetuate racial stereotypes?

- How does the school-to-prison pipeline and, later, the criminal justice system perpetuate the racial wealth gap?

- What historical laws and policies have impacted people of color in the United States?

- If you were explaining redlining to a friend, how would you describe it?

- In what ways can you still see the impacts of redlining today?

- How does completing your annual tax return impact your experience of financial stability? How might this be different for others?

- Identify the three main kinds of loans outlined in this chapter. Why are they relevant in a discussion of social justice? Are there other financial policies or laws relevant in a discussion of social justice?

- Discuss safety net priorities in the context of healthcare. How do we provide care to the most vulnerable?

- Discuss the school-to-prison pipeline as an issue of social justice. What can we do to impact this?

- What laws or policies are missing in this chapter that also impact the experience of marginalization in the United States?

Thoughts from the Author

I spent so much time on this chapter and want to acknowledge that there are still things missing. There is just so much out there—I could probably write a book on each. I have tried to highlight legislation and policy that is useful and relevant and frames social justice in useful, impactful ways. I have so much passion around policy and the impact that bad policy has on people—it is a passion that has grown through the writing of this chapter, and passion I hope to pass on to you too!

Sincerely,

Bernadet DeJonge

References

Akin, J. (2022, July 2). What is a subprime mortgage? Experian. https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-a-subprime-mortgage/

Alio, A. P., Wharton, M. J., & Fiscella, K. (2022). Structural racism and inequities in access to Medicaid-funded quality cancer care in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 5(7). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22220

Batchelder, L., & Leierson, G. (2023, January 20). Disparities in the benefits of tax expenditures by race and ethnicity. US Department of the Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/disparities-in-the-benefits-of-tax-expenditures-by-race-and-ethnicity

Best, R., & Mejia, E. (2022, February 9). The lasting legacy of redlining. FiveThirtyEight. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/redlining/

Blitzman, J. (2021, October 12). Shutting down the school-to-prison pipeline. Human Rights Magazine, 47(1). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/empowering-youth-at-risk/shutting-down-the-school-to-prison-pipeline/

Bowling Green State University. (n.d.). Laws and race. Race in the United States, 1880-1940, Student Digital Gallery, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH, United States. https://digitalgallery.bgsu.edu/student/exhibits/show/race-in-us/laws-and-race

Broady, K., McComas, M., & Quazad, A. (2021, November 2). An analysis of financial institutions in Black majority communities: Black borrowers and depositors face considerable challenges in accessing banking services. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/an-analysis-of-financial-institutions-in-black-majority-communities-black-borrowers-and-depositors-face-considerable-challenges-in-accessing-banking-services/

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2020). Policy basics: Introduction to Medicaid. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/introduction-to-medicaid

Collins, S. R., Haynes, L. A., & Masitha, R. (2022, September 29). The state of U.S. health insurance in 2022: Findings from the Commonwealth Fund biennial health insurance survey. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/sep/state-us-health-insurance-2022-biennial-survey

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (2017). What is a subprime mortgage? https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-is-a-subprime-mortgage-en-110/

Cyrus, R. (2023, June 5). Predatory lending’s prey of color. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/economy/2023-06-05-predatory-lendings-prey-of-color/

Davis, C., Hill, M., & Wiehe. (2021, April 2). Sales taxes widen the racial wealth divide. States and cities have far better options. Inequality.org. https://inequality.org/research/taxes-racial-equity/

Elias, M. (2013, Spring). The school-to-prison pipeline. Learning for Justice. https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/spring-2013/the-school-to-prison-pipeline

Goddess Mia [@evelrooted]. (2023, August 10). Racism is the reason healthcare is not an American right [Video]. Tik Tok. https://www.tiktok.com/@evelrooted/video/7262512583071042858

Grabenstein, H., & Khan, S. (2022, April 11). Student loan debt has a lasting effect on Black borrowers, despite the latest payment freeze. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/student-loan-debt-has-a-lasting-effect-on-black-borrowers-despite-the-latest-freeze-in-payments

Haldar, S., Rudowitz, R., & Artiga, S. (2023, June 2). Medicaid and racial health equity. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-efforts-to-address-racial-health-disparities/

Hanson, M. (2023, September 3). Student loan debt by race. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-race

Hébert-Dufrense, L., Waring, T. M., St-Onge, G., Niles, M. T., Corlew, L. K., Dube, M. P., Miller, S. J., Gotelli, N., & McGill, B. J. (2022). Source-sink behavioural dynamics limit institutional evolution in a group-structured society. Royal Society Open Science, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.211743

Hill, M., Davis, C., & Wiehe, M. (2021, March 31). Taxes and racial equity: An overview of state and local policy impacts. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. https://itep.org/taxes-and-racial-equity/

History.com. (2023). Jim Crow laws. https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws

Huang, C-C., & Taylor, R. (2019, July 25). How the federal tax code can better advance racial equity: 2017 tax law took step backward. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-better-advance-racial-equity

Infanti, A. C. (2019, April 11). How US tax laws discriminate against women, gays and people of color. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-us-tax-laws-discriminate-against-women-gays-and-people-of-color-115283

Investopedia. (2020). What is a housing bubble? Definition, causes, and recent examples. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/housing_bubble.asp

Jackson, C. (2021, August 17). What is redlining? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/realestate/what-is-redlining.html

KFF. (2019, February 13). An overview of Medicare. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicare/

Levin, L. (2019). The Queen: The forgotten life behind an American myth. Back Bay Books.

Medicare.gov. (n.d.). Mental health care (outpatient). https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/mental-health-care-outpatient

Mehkeri, Z. A. (2014). Predatory lending: What’s race got to do with it. Public Interest Law Reporter, 20(1), Article 9. http://lawecommons.luc.edu/pilr/vol20/iss1/9

Mustaffa, J. B., & Davis, J. C. W. (2021, October 20). Jim Crow debt: How Black borrowers experience student loans. The Education Trust. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Jim-Crow-Debt_How-Black-Borrowers-Experience-Student-Loans_October-2021.pdf

Nembhard, S., & Robin, L. (2021, August). Racial and ethnic disparities throughout the criminal legal system: A result of racist policies and discretionary practices. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104687/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-throughout-the-criminal-legal-system.pdf

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

PBS. (n.d.). Jim Crow laws. American Experience. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/freedom-riders-jim-crow-laws/

Perry, A. M., Steinbaum, M., & Romer, C. (2021, June 23). Student loans, the racial wealth divide, and why we need full student debt cancellation. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/student-loans-the-racial-wealth-divide-and-why-we-need-full-student-debt-cancellation/

Roth, M.S. (2022, February 15). The debt trap: How court debt widens the racial wealth gap. Shelterforce.https://shelterforce.org/2022/02/15/the-debt-trap-how-court-debt-widens-the-racial-wealth-gap/

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright.

The Sentencing Project. (2018, April 19). Report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/report-to-the-united-nations-on-racial-disparities-in-the-u-s-criminal-justice-system/

Srakocic, S. (2021, June 8). When is the Medicare waiting period waived? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/medicare/medicare-waiting-period-waived

Steinberg, D., Weber, E., & Woodworth, A. (2021, June 22). Medicare’s discriminatory coverage policies for substance use disorders. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/medicare-s-discriminatory-coverage-policies-substance-use-disorders

Wiley, E. (2022, July 20). How racism in the courtroom produces wrongful convictions and mass incarceration. Legal Defense Fund. https://www.naacpldf.org/judicial-process-failures/

Yearby, R., Clark, B., & Figueroa, J. F. (2022). Structural racism in historical and modern US health care policy. Health Equity, 41(2), 187-194. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01466

Young, C. L. (2020, February 19). There are clear, race-based inequalities in health insurance and health outcomes. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/there-are-clear-race-based-inequalities-in-health-insurance-and-health-outcomes/

Media Attributions

- Silhouettes © Fitsum Admasu is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Milwaukee Redlining © National Archives is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Graffiti protesting gentrification © Shiraz Chakera is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Payday Loans © swanksalot is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Man in gray crew-neck shirt © Mubarak Showole is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Medical consultation © National Cancer Institute is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Razor wire © Hédi Benyounes is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license