9 Gender and Sexuality in the United States

Nikki Golden and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will gain an understanding of the influence of early Protestants on the sociocultural norms of gender and sexuality in the United States.

- The reader will gain knowledge of critical events in the history of the LGBTGEQIAP+ community in the United States.

- The reader will be introduced to state and federal discriminatory laws against the LGBTGEQIAP+ community in the United States.

Gender and sexual sociocultural norms in the United States have a multitude of influences. However, early English colonists and their Protestant religious beliefs remain the most decisive influence on gender and sexual norms in the United States. In this chapter, gender and sexuality in North American colonial and post-colonial periods are discussed. In addition, this chapter will address critical events in advancing social justice for the gay and transgender community, state and federal discriminatory laws against the gay and transgender community, and specific social justice movements in the gay and transgender community.

- Lesbian

- Gay

- Bisexual

- Trans, Transgender, and Two-Spirit

- Gender-Expansive

- Queer and Questioning

- Intersex

- Agender, Asexual, & Aromantic

- Pansexual, Polygender, & Poly Relationships

- + Other related identities (SAIGE, n.d.)

Discussion Questions

- Did you know what all the letters in the LGBTGEQIAP+ acronym stood for?

- What might need to be added to the abbreviation?

Colonial Period

When English colonists arrived in North America, they brought strict religious and sociocultural beliefs. The Puritans, a sect of English Protestants, were some of the earliest colonists in North America. The Puritans rejected the Church of England and what they considered a decadent English society. In fact, they compared England to the biblical city of Sodom: traditionally recognized as a city destroyed by the sin of homosexuality. The Puritans believed that “England’s corruption would be punished by God” (Cooke, 2014, p. 334). Faced with religious persecution, the Puritans fled England.

Since their introduction, Puritans’ religious beliefs and system of law had, and continues to have, a tremendous influence on gender and sexual norms in the United States. The Puritans had a clear definition of what they considered appropriate gender expression and did not tolerate the blurring of gender roles (Smithers, 2022). Puritans idealized masculinity, and any man who engaged in behavior deemed as feminine, including having long hair, was judged as immoral. Similarly, Puritan women who stepped outside of their prescribed gender role were excommunicated or physically punished (Faderman, 2022).

Additionally, the Puritans had a rigid understanding of appropriate expressions of sexuality. For instance, sodomy was defined as any sexual acts deemed unnatural and included sexual acts between men, between men and women outside of marriage, and men with animals (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012; Faderman, 2015). Puritans identified sodomy as a “sinne{sic} not once to be named” (Thompson, 1989, p. 31) and considered acts of sodomy to be worse than adultery. Not only were the acts of sodomy considered unnatural, but the Puritans believed that the people who engaged in sodomy were unnatural themselves (Bronski, 2011; D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012).

The Puritans utilized English laws, such as King Henry VIII’s Buggery Act of 1533, as a template to create the first sodomy laws in North America (Bronski, 2011). However, the Puritans were not the only English colonists to enact sodomy laws. According to Bronski, all early English colonies had sodomy laws to regulate sexual behavior, though these laws varied due to differing religious beliefs and demographics. For instance, Chesapeake Bay colonists outlawed crimes of sin, which included adultery, rape, and sodomy, and equated such acts with offenses such as treason, murder, and witchcraft. Although sodomy laws technically concerned both men and women, the majority of those convicted and punished were men (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012).

Oppression against gay male sex is documented throughout English history. For example, in 13th-century England, there was a legal document called the “Fleta,” which punished sodomy by burying or burning men alive. In 1533, King Henry VIII criminalized gay male sex through the Buggery Act, which made sex between men punishable by death, typically by public hanging. This punishment was common across England for nearly 300 years of their history (Historic England, n.d.).

Discussion Questions

- How might these historic laws, which regulated sexual behavior, have influenced the Puritans who came to the colonies?

- How might these historic laws, which regulated sexual behavior, influence the experience of LGBTGEQIAP+ individuals in the United States today?

As acts of sodomy challenged the paradigm of reproductive sexuality, colonial sodomy laws were strict, and punishments severe (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012). According to D’Emilio and Freedman, it was not unusual for English colonies to prescribe “corporal or capital punishment, fines, and in some cases, banishment” (p. 18). However, as sexual mores had shifted by the late 1700s, Americans became less concerned about the sin of sodomy, instead worrying that sodomy “offended a natural order” (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012, p. 122).

Sexual Identity Defined

Early English colonists did not recognize homosexuality as a personal identity. However, a new understanding of those who engaged in acts of sodomy had developed by the end of the American Revolutionary War (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012). It was in the 1800s that the “binding of sexuality and identity” (Kunzel, 2018, p. 1563) occurred, and the concept of sexual identity emerged in the United States.

By the early 1800s, sexologists theorized that anyone who was sexually attracted to or engaged in sexual acts with someone of the same gender were “inverted” (Kunzel, 2018). Throughout the 1800s and the mid-1900s, medical professionals used the clinical term invert, but by the mid-1900s they began using the term homosexual to describe individuals who engaged in and preferred same-gender sexual behaviors.

Law enforcement used derogatory terms such as sexual psychopaths, before employing additional terms such as “degenerate or pervert” (Charles, 2015, p. 12) to describe homosexuality. Commonly used terms included pansy, fairy, and nancy boy for gay men and she-men or bulldagger for women. In the 1800s and early 1900s, gay men self-identified as fairies or as queer, though by the 1930s gay became the more acceptable term. However, women who identified as gay only used that term until the 1920s, when many began to self-identify as either bisexual or lesbian (Charles, 2015; Faderman, 2022).

By the mid-1900s, homosexuality was defined “less by a type of sexual relations than by a certain quality of sexual sensibility…the sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species” (Foucault, 1978, p. 43). Regardless of their gender, homosexuals were now considered a new category of humans.

Sexual Renaissance

During the 1920s, the United States “witnessed a permissiveness among the more sophisticated to experiment not only with heterosexuality but with bisexuality as well” (Faderman, 2022, p. 62) in certain parts of the country. Artists and bohemians were open to sexual experimentation, although “bisexuality was far more easily understood…particularly if it ended in heterosexuality” (Faderman, 2022, p. 85).

During this time, some women who identified as lesbians created their own subculture separate from gay men (Faderman, 2022). The Black lesbian subculture was established in Harlem, whereas the White lesbian subculture was established in Greenwich Village. Many believed that for women, bisexuality was a phase and that “it could be gotten out of a woman by a good psychoanalyst or a good man” (Faderman, 2022, p. 85).

From 1918 to 1937, Harlem was considered a cultural mecca for not only Black Americans, but also for those in the larger gay community. At the same time, there was a cultural “renaissance in Harlem…there was also a burgeoning ‘queer’ renaissance, which was connected with the increased visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered individuals” (Wilson, 2010, p. 28).

Black lesbian performers sang songs that “opened up a space for a variety of sexual identities to emerge” (Berry & Gross, 2020, p. 130). Nightclubs that catered explicitly to “the drag subculture, and acts featuring ‘pansies’ and ‘bulldaggers’ were not altogether uncommon” (Wilson, 2010, p. 39), and female impersonators were a consistent presence in the Harlem nightclub scene.

Video: The (Gay) Harlem Renaissance

Video: The Queer History of the Harlem Renaissance

Discussion Questions

- What did you learn about the history of being gay from these videos?

- Why do you think you may not have been taught about the Harlem Renaissance in school?

- How do you think the gay renaissance of Harlem impacted what Harlem is today?

Founded in 1869, The Hamilton Lodge Ball , was an annual masquerade and civil ball sponsored by a fraternity of Black men. Additionally, it served as a cross-dressing ball. By the 1920s, the Hamilton Lodge Ball recorded as many as 1,500 attendees. Due to its popularity, other drag balls were established; as many as 7,000 people attended them in Harlem. These balls included racially integrated audiences, contestants, and judges (Wilson, 2010).

Discussion Question

- Did you know about the drag balls in Harlem and beyond? Why do you think you may not have known about them?

Legislating Sexuality

Throughout the early 1900s, fear mongering about homosexuals—or, as they were often referred to in the media, sexual psychopaths—permeated American culture (Charles, 2015). As early as 1937, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) collected data on gay people under the guise that they were sex offenders. The director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, justified this data collection as a means to keep the American public safe from sexual perverts.

Hoover and his contemporaries believed that gay people were a risk to national security. In fact, due to the state and federal laws that made homosexuality illegal in the United States, gay people or people who engaged in behavior deemed as homosexual were at risk of being blackmailed (Charles, 2015). As the United States entered World War II, paranoia about gay people increased.

Similar to McCarthy’s hunt for communists during the Red Scare, the Lavender Scare was a hunt for gay people working in the United States government. However, unlike McCarthy’s Red Scare, the Lavender Scare began in the late 1930s and lasted until the late 1970s. “Originating as a partisan political weapon in the halls of Congress, it sparked a moral panic within mainstream American culture and became the basis for a federal government policy that lasted nearly twenty-five years and affected innumerable people’s lives” (Johnson, 2023, p. 9).

Video: The Lavender Scare

Discussion Questions

- Did you know about the Lavender Scare? Why do you think this might not have been taught as part of history like the Red Scare?

- Do these fears sound familiar? What kinds of issues are we facing today around gender identity and expression stemming from similar fears?

- What role does the media play in these fears? Compare how the media might have impacted the Lavender scare and how it represents LGBTGEQIAP+ people today.

- The FBI finally destroyed the files it had collected for Hoover’s Sex Deviates program in 1978, five years after Hoover’s death (Cervini, 2020). Why do you think it took so long for the FBI to destroy the files from the Sex Deviates program?

In spite of persecution, a gay subculture thrived in Washington, D.C. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies increased job opportunities and brought thousands of people to the United States capital to work in the federal government. The combination “of neutral civil service entrance examinations and a feminized work culture made government offices in Washington prior to the 1950s hospitable to gays and lesbians” (Johnson, 2023, p. 45).

As in the early years of industrialization within urban areas, the combination of employment and living in a new environment meant that gay people were able to be more open about their sexuality. In Lafayette Park—one block from the White House—gay men would meet, socialize, and occasionally engage in sexual activities. The neighborhoods surrounding Lafayette Park were the epicenter of gay social life. “Gay men and lesbians in the nation’s capital in the 1930s and 1940s enjoyed a comfortable working environment in the federal government and a vibrant social life in a fast-growing city” (Johnson, 2023, p. 51).

After World War II, there was a backlash towards the gay community. The American public “had a growing sense that the country’s moral codes were loosening and that homosexuality was becoming more prevalent or at least more visible” (Johnson, 2023, p. 53). The combination of the release of the Kinsey Report, increased publication of novels focused on gay desire, and sex crimes highlighted in the media all flamed the fears of gay people and homosexuality. Ultimately, the culmination of these concerns led to increased scrutiny on the gay subculture in Washington, D.C.

Read through a summary of The Kinsey Report and related later surveys.

The Kinsey Report was a scientific publication that came out in 1948. It revealed research that stated that Americans were more sexually active than many expected in many ways. Additionally, it reported significant homosexual experiences. Scientists championed it as a much-needed educational and diagnostic tool, while others claimed it was an affront to American morality (PBS, n.d.).

Discussion Questions

- Discuss prevailing attitudes toward sex and gender when the Kinsey report was published. How did the prevailing attitudes towards sexuality influence the reception of the Kinsey Report?

- How did Kinsey’s use of a scale (the Kinsey Scale) to measure sexual orientation challenge the binary view of sexuality prevalent at the time?

- How did the Kinsey Report affect the visibility and understanding of the gay community?

- How did Kinsey’s findings challenge or reinforce existing stereotypes about homosexuality?

In 1948, the United States Congress held hearings on the need for a Sexual Psychopath Law in Washington, D.C. to control the gay community. “Beyond policing behavior…government officials wanted to contain what they saw as the increasing openness, even arrogance, of homosexuals” (Johnson, 2023, p. 58). The law was named after its sponsor, Congressmember Arthur Lewis Miller, who believed “the homosexual’s instinct [for moral decency] breaks down, and he is driven into abnormal fields of sexual practice” (Faderman, 2015, p. 4).

Under the Miller Law, any individual charged with sodomy was required to be evaluated by a psychiatric team. If a psychiatric team deemed an individual as a sexual psychopath, they were committed to a psychiatric hospital until they recovered enough to stand criminal trial. If convicted in a court of law, individuals could face up to twenty years in prison (Faderman, 2015). In 1948, President Truman signed the Miller Sexual Psychopath Law in Washington, D.C.

The Miller Law gained support through inciting fears about the dangers of homosexuality to children. However, once it was passed, it was used to bolster the criminalization of gay sexuality (Johnson, 2023). The Miller Sexual Psychopath Law “prohibited taking ‘into his or her mouth or anus the sexual organ of any other person or animal,’ in addition to the reciprocal act” (Cervini, 2020, p. 38).

As the Miller Law was passed, the U.S. Park Police launched their “Pervert Elimination Campaign…that mandated the harassment and arrest of men in known gay cruising areas” (Johnson, 2023, p. 59). The campaign emboldened the U.S. Park Police to harass men, primarily gay men, without any restrictions. If a man was near a known gay cruising area, they could be stopped and interrogated by the U.S. Park Police. Hundreds of men were arrested, though most were not convicted due to a lack of evidence. However, their personal information—such as their names, occupations, and fingerprints—were collected.

As a consequence of the Red Scare and Lavender Scare, the media, and the collective fears of the American public, 29 states had sexual psychopathy laws by 1957. “In only a decade, homosexuals had graduated from criminals to merely incarcerated after homosexual activity to mentally ill criminals” (Cervini, 2020, p. 38). Individual states’ sexual psychopathy laws, such as the Miller Act, outlawed anal and oral sex. Depending upon the state, punishment included “indefinite confinement” in a prison or mental institution (Duberman, 2019, p. xxiv). Gay people were sent to mental institutions and “treated” with shock therapy, lobotomies, and castration (Cervini, 2020). By the end of the 1960s, sodomy was illegal in all 50 states (Hagai & Crosby, 2016).

In the 1970s, some states repealed their sodomy laws. However, many of the old sodomy laws were replaced with more severe laws. For example, in 1971, Texas repealed its sodomy law, but by 1973 a new law was passed. Unlike Texas’ old sodomy law, which concerned sodomy acts regardless of who engaged in them, the new law “targeted gays and lesbians only, whether they were caught having sex in public or in private, whether orally or anally, whether with mouth, penis, or dildo” (Faderman, 2015, p. 539). Gay activists attempted to challenge states’ sodomy laws with little success.

A 1976 case, Doe v. Commonwealth’s Attorney, challenged Virginia’s sodomy law, arguing that it violated individuals’ constitutional rights of privacy, freedom of speech, and due process, along with the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Ultimately, this case failed, but it set a precedent for future legal challenges to similar laws and helped to raise awareness about the discrimination faced by gay individuals in the United States. “The ripple effects of the loss of Doe v. Commonwealth’s Attorney were felt in Virginia for a long time” (Faderman, 2015, p. 540).

By 1979, 20 states had repealed their sodomy laws. Some states, such as Arkansas, reinstated their sodomy laws after the state’s religious conservatives protested (Bronski, 2011). However, the remaining states’ sodomy laws continued to be enforced. In 1986, 29-year-old Michael Hardwick was arrested under Georgia’s sodomy laws for engaging in oral sex with another man; their legislation included a punishment of up to 20 years in prison. Though Hardwick was not prosecuted, he sued Georgia’s Attorney General, claiming he could eventually be prosecuted for his consensual gay sex. In turn, his case went to the United States Supreme Court (Faderman, 2015). However, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Bowers v. Hardwick that Georgia’s sodomy laws were constitutional (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012). Chief Justice Burger wrote in his concurring opinion “To hold that the act of homosexual sodomy is somehow protected as a fundamental right would be to cast aside millennia of moral teaching” (Garretson, 2018, p. 88). Ultimately, in 1998—12 years after Bowers v. Hardwick—Georgia’s Supreme Court repealed the 156-year-old sodomy law (Marcus, 2002).

In 2003, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Lawrence v. Texas that state sodomy laws violated an individual’s right to privacy. Their ruling in Lawrence v. Texas represented the end of “an almost five-hundred-year tradition in Anglo-American law” (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012, p. 374). Additionally, this ruling opened the door for other changes to law and legislation to protect the gay community’s constitutional rights.

Video: Queer History is World History: Reframing Curriculum by Madeline English

Discussion Questions

- How does the video define “queer history,” and why is it essential to include it in the broader context of world history?

- How can educators effectively incorporate queer history into existing historical narratives? Why is this important?

- How has the exclusion of queer history affected the understanding of world history?

- How did the video challenge or change your perception of world history?

- What other resources or perspectives would you like to explore to deepen your understanding of queer history?

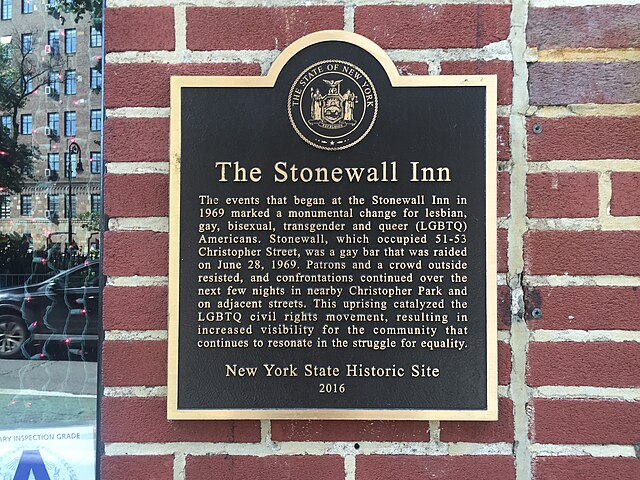

Stonewall Inn Riots

In the 1960s, the gay bar scene in New York City was controlled by the mafia and the police. As the only gay bars in New York City were owned and operated by the mafia, the proprietors had no incentive to cater to their customers. Instead, they spent as little money as possible and profited considerably; the greatest share was spent paying local police for protection (Duberman, 2019).

In 1966, the mafia opened the Stonewall Inn. The Stonewall Inn was, at best, a dive bar in Greenwich Village, New York. At the time, it had no running water and was semi-regularly raided by the police. Nevertheless, the Stonewall Inn had a diverse clientele and was a relatively safe place for the gay community. White gay men, gay people of color, and drag queens were regular patrons at the Stonewall Inn (Charles, 2015; Duberman, 2019). New York City’s legal drinking age was 18 and customers’ ages ranged from late teens to early thirties. Customers were primarily men, including White gay men, known as “the chino-penny loafer crowd” (Duberman, 2019, p. 234) as well as young drag queens, some of whom were homeless.

The Stonewall Inn was “a real dive, an awful, sleazy place” (Duberman, 2019, p. 224). Nevertheless it was the most popular gay bar in the area, primarily because it was the only gay bar in New York that allowed customers to dance. Although the mafia owners paid for protection at the Stonewall Inn, it was still regularly raided by police as all gay bars were. Police raids were tolerated by bar owners and customers alike because there was no other option. During a typical police raid, “the only people who would be arrested would be those without IDs, those dressed in the clothes of the opposite gender, and some or all of the employees” (Duberman, 2019, p. 237). As a courtesy, police usually notified owners when a raid was scheduled. However, on June 27, 1969, police conducted an unannounced raid at the Stonewall Inn.

The raid at the Stonewall Inn began as per usual; IDs were checked and some employees were arrested, as well as a few drag queens. However, eyewitness accounts contradict one another on the cause of the riots: some claimed it was because police were overly rough with a local drag queen, while others said it was because of the mood of the outside crowd (Duberman, 2019). “Several incidents were happening simultaneously. There was no one thing that happened or one person, there was just a a flash of group—of—anger” (Duberman, 2019, p. 243). Consequently, the crowd protested the treatment of the arrestees and the presence of the police—who were surprised by the ire of the crowd. “By now, the crowd had swelled to a mob, and people were picking up and throwing whatever loose objects came to hand—coins, bottles, cans, bricks ” (Duberman, 2019, p. 244). Outnumbered, the police retreated into the Stonewall Inn and called for reinforcements. During the melee, a small fire started inside the Stonewall Inn while police were trapped inside.

The Tactical Patrol Force (TPF), “a highly trained, crack riot-control unit” (Duberman, 2019, p. 247) of the police, was summoned. Armed with billy clubs and tear gas, the TPF marched on the protestors. In turn, the protestors retreated, before doubling back on the TPF, and attacked them. This continued until the TPF responded with violence: “As they were badly beating up on one effeminate-looking boy, a portion of the angry crowd surged in, snatched the boy away, and prevented the cops from reclaiming him” (Duberman, 2019, p. 248).

Some protesting drag queens conducted a chorus line to taunt the TPF; “It was a deliciously witty, contemptuous counterpoint to the TPF’s brute force that transformed an otherwise traditionally macho eye-for-eye combat and that provided at least the glimpse of a different and revelatory kind of consciousness” (Duberman, 2019, p. 248). Other protestors chased two police officers until they fled the scene. Police cars were damaged, and blood was spilled.

The TPF and fellow police had always used brute force and violence against the gay community. They expected the protestors to cower, but they did not. By the end of the first night, 13 protestors were arrested and many more were injured. “Four big cops beat up a young queen so badly—there is evidence that the cops singled out feminine boys—that she bled simultaneously from her mouth, nose, and ears” (Duberman, 2019, pp. 248-249). Four police officers sustained injuries. However, by 3:35 am, the area surrounding the Stonewall Inn was temporarily cleared.

The following day, the media began to cover the protests. Spurred by media reports, locals from the gay community gathered at the Stonewall Inn to witness the aftermath. An impromptu block party started; people shouted, “gay power,” and drag queens resumed their chorus lines (Duberman, 2019). As more people gathered, the TPF returned to the Stonewall Inn and attempted to disperse the crowd. However, by the time the TPF arrived, thousands of people were celebrating gay power.

When the fearless chorus line of queens insisted on yet another refrain, kicking their heels high in the air, as if in direct defiance, the TPF moved forward, ferociously pushing their nightsticks into the ribs of anyone who didn’t jump immediately out of their path (Duberman, 2019, p. 251).

The second night of the Stonewall Inn riots had begun. According to eyewitnesses, “all hell broke loose” (Duberman, 2019, p. 251). Protestors stopped cars and attacked police—throwing bottles, bricks, and concrete blocks at the police. “Twice the police broke ranks and charged into the crowd, flailing wildly with their nightsticks” (Duberman, 2019, p. 253) and clubbed protestors to the ground. The second night of the protests continued until 4 a.m. and only ended when the police withdrew their units from the area surrounding the Stonewall Inn. “After the second night of rioting, it had become clear to many that a major upheaval, a kind of seismic shift, was at hand…” (Duberman, 2019, p. 254). Gay activists called the media, created protest literature, handed out flyers, and called in reinforcements from gay organizations.

The following day—a Sunday—was mostly calm in the streets surrounding the Stonewall Inn. Police patrolled the area and “seemed spoiling for trouble” by yelling “faggots” out their car windows (Duberman, 2019, p. 256). The Stonewall Inn reopened for business and customers returned. Monday and Tuesday nights also remained quiet, but protestors returned to the streets surrounding the Stonewall Inn by Wednesday night.

Approximately 2,000 protestors gathered; they lit trash cans on fire, threw improvised projectiles, and shouted at the police. In response, the “TPF wielded their nightsticks indiscriminately, openly beating people up, left them bleeding on the street, and carted off four to jail on the usual charge of harassment” (Duberman, 2019, p. 257). Sunday night was the last night of the Stonewall Inn riots. By the end, it was estimated that approximately 400 police officers confronted approximately 2,000 protestors during the Stonewall Inn riots. “It was a full-fledged gay uprising” (Charles, 2015, p. 307).

Although the Stonewall Inn riots did not stop police harassment of the gay community, nor raids on gay bars, their demonstrations left a profound impact on the gay community. Media coverage of the riots exposed the public to gay people fighting for their rights as Americans. Gay people across the United States felt empowered to resist police brutality and harassment (Duberman, 2019). Even the police recognized a power shift. Deputy Inspector Pine stated, “For those of us in public morals, things were completely changed…suddenly they were not submissive anymore” (Duberman, 2019, p. 257).

Video: Stonewall at 50 from NYU

Discussion Questions

- What social, political, and legal conditions for LGBTGEQIAP+ individuals existed in the United States prior to the Stonewall Riots? How did these conditions contribute to the tensions leading up to the riots?

- How did the Stonewall Riots serve as a turning point for the LGBTGEQIAP+ rights movement?

- How did the Stonewall Riots highlight issues of intersectionality within the LGBTGEQIAP+ community, particularly regarding race, gender, and class?

- What is the significance of Pride Month, and how is it connected to the legacy of Stonewall?

- How does learning about the Stonewall Riots affect your understanding of LGBTGEQIAP+ history and the fight for civil rights?

- What actions can individuals and communities take today to honor the legacy of the Stonewall Riots and continue the fight for equality?

Organizing Gay Pride

After the Stonewall Inn riots, several new gay activist organizations were established. One group of young activists formed the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). According to Faderman (2015), the GLF “formed with the realization that sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished” (p. 199). GFL’s members wanted to create social change, not just a safe place for the gay community (Duberman, 2019).

Members of the GLF had been involved with other social justice movements, including the Civil Rights movement and the Women’s Rights movement. They wanted to use more radical approaches to get the American public’s attention (Duberman, 2019) and support other marginalized communities. Though many members appreciated the GLF’s radical approach, they did not appreciate its diversified focus, such as supporting the Black Panther Party, which had often been overtly anti-gay (Faderman, 2015).

In December 1969, former members of the GLF established the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA; Bronski, 2011). The GAA was considered to be a bridge between the more conservative gay organizations and the radical GLF. GAA members “agreed that fighting for gay and lesbian rights didn’t require tearing down the American system. They only wanted to open it up to gay people” (Federman, 2015, p. 214).

The AIDS Movement

The 1980s were a sociocultural backlash to the social justice-oriented 1960s and 1970s. Ronald Reagan was the President of the United States—conservatives were in power. During this time, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Cold War, and nuclear war was a tangible threat. However, another danger emerged during the 1980s: the AIDS epidemic.

AIDS Epidemic

On June 5, 1981, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) newsletter reported five cases of “unusual pneumonia” (Bronski, 2011, p. 224) in Los Angeles. A month later, the New York Times published an article about a rare cancer that was identified in 41 gay men. By the end of 1981, there had been at least 121 deaths attributed to a “gay-related immune deficiency” or the “gay plague” (Bronski, 2011, p. 224). The medical community was first baffled, then alarmed. It was not until 1983 that researchers were able to identify the virus ultimately known as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the cause of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). By the end of 1982, 634 had been diagnosed—of those, 200 died. By 1990, over 31,000 people had died from AIDS-related illnesses.

Initially, AIDS was considered a gay disease because the first victims were gay men. Gay men, who already faced a great deal of discrimination, were now viewed as carriers of a deadly disease. The stigma of AIDS was intense, particularly before its transmission was understood. As a consequence, prejudiced views of the AIDS epidemic caused a great deal of harm to the gay community. In hospitals, medical professionals were afraid to touch AIDS patients, who were often left alone in their hospital beds unattended to. Even in death, the stigma of AIDS was devastating. After AIDS patients died, they were put into black trash bags; many funeral homes refused to care for their bodies (Faderman, 2015).

As the AIDS epidemic progressed, anyone who was found to be at high risk of contracting the disease was discriminated against, particularly those who used drugs intravenously. This individual discrimination led to discriminatory laws explicitly against people with HIV and/or AIDS. Furthermore the federal government, as well as individual state governments, did not apply additional resources to education or research to combat the disease. “The political and legal backlash engendered by the AIDS epidemic was tremendous” (Bronski, 2011, p. 230). By 1984, large cities closed the bathhouses and clubs that catered to gay men, as, according to officials, they were hazards to public health and safety. In a New York Times article, William F. Buckley Jr.—founder of the conservative journal National Review—suggested that “everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals” (Bronski, 2011, p. 230).

By 1986, the AIDS epidemic continued to decimate the gay community. Although gay men were no longer the only known victims of AIDS, they remained the primary target of public fear, anger, and discrimination—“Brutal attacks on gay men were up everywhere” (Faderman, 2015, p. 424). Within the gay community’s safe haven of San Francisco, there were 60 beatings of gay men reported to the police in one month; it is unknown how many occurred that were not reported. For gay activists, it felt as if all the progress that had been made toward acceptance by the American public was dying, as were many of their community members.

Video: How The AIDS Crisis Changed The LGBT Movement

Discussion Questions

- What were the immediate effects of the AIDS crisis on the LGBTGEQIAP+ community in terms of health, social stigma, and community cohesion?

- How did the government’s initial response to the AIDS crisis affect the LGBTGEQIAP+ community?

- How did the AIDS crisis highlight issues of intersectionality within the LGBTGEQIAP+ community, particularly regarding race, gender, and socioeconomic status?

- In what ways did the AIDS crisis transform the goals and strategies of the LGBTGEQIAP+ rights movement?

AIDS Activism

By the early 1980s, the gay liberation movement had lost momentum and support (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012). The emergence of the AIDS epidemic devastated the gay community as the disease killed many gay activists. Consequently gay activists who had not contracted AIDS shifted their focus from gay community rights to advocating for resources to combat the disease (Bronski, 2011; Marcus, 2002). The devastation of AIDS and the lack of federal funding and resources became the new driving force behind gay activists. Though the federal government and President Ronald Reagan ignored those suffering from the AIDS epidemic, others did not. Groups such as the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), AIDS Project LA (APLA), the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), and the Gay and Lesbian Latinos Unidos (GLLU) were formed (Bronski, 2011; Duberman, 2019).

In 1986, Marty Robinson formed the Lavender Hill Mob. Known as the Mobsters, the group was active during the AIDS crisis. The Mobsters protested the Catholic Church and Senator Alfonse D’Amato of the State of New York. The Mobsters were the first gay group to reclaim the upside-down pink triangle that the Nazis used to label gay men in World War II, and they wore it when they went to protest the CDC (Faderman, 2015).

Discussion Questions

- The mobsters took on powerful opponents in their protests. What do you think led them to this?

- How did the social and political climate of the 1980s impact the formation of the Lavender Hill Mob?

- The mobsters reclaimed the upside-down pink triangle the Nazis used to label gay men. What does this mean? What other examples can you think of reclaiming something discriminatory?

- In what ways did the Lavender Hill Mob’s protests contribute to the broader gay rights movement?

In 1982, Larry Kramer established the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). The GMHC was created to provide care for AIDS patients that the federal government, and sometimes even families, would not. GMHC gathered volunteers to visit AIDS patients, clean their apartments, take care of their pets, and help them navigate their medical needs (Faderman, 2015). GMHC created a 24-hour hotline, ran therapy groups, recruited lawyers, and raised money for the care of those with AIDS (Duberman, 2019; Faderman, 2015).

Although Larry Kramer recognized that organizations like GMHC were doing good work, he knew it was not enough to stop the AIDS epidemic. In 1987, inspired by the Mobsters, Kramer established the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) group.

Video: How ACT UP Flipped the Script on AIDS and Gay Rights

Video: Larry Kramer 20th Anniversary ACT-UP AIDS Coalition Unleash Power

Discussion Questions

- Discuss your thoughts on these videos. What impacted the organization? What were the impacts of these gay advocacy groups?

- What might have happened to members of the gay community if these groups had not formed and advocated for them?

Chapters of ACT Up not only formed in major cities with large gay populations, such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco, but also in cities that were not known as gay havens, including Oklahoma City, Orlando, and Shreveport (Faderman, 2015). ACT Up activists used the slogan Silence = Death and the upside-down pink triangle. Additionally, ACT Up also used picketing, protesting, and the tactic of Zaps: spontaneous public demonstrations designed to increase the visibility of their cause. ACT Up activists forced the office of the United States Food and Drug Administration to close, shackled themselves inside the headquarters of Burroughs Wellcome, a major pharmaceutical company, and caused commotion on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012).

Were you aware of the Zaps activist strategy? First used by gay activists in the early 1970s, Zaps combined protest with performance art. Gay activists used Zaps to disrupt and interrupt. Typically used to gain media coverage, Zaps were theatrical, active, and impossible to ignore. Often organized on short notice, Zaps were an effective way to confront discrimination directly and remind the American public of the existence of the gay community and, during the 1980s, the AIDS crisis (Bronski, 2011; Faderman, 2015).

Video: GAA Zaps

Reading: Out History Exhibit by Lindsay Branson

Discussion Questions

- How did the GAA ensure that Zaps were impactful and received widespread attention?

- How did the GAA use public demonstrations to put pressure on politicians and encourage other gays and lesbians to join their cause?

- What role did the media play in documenting and spreading the message of the GAA’s Zaps?

- Why do you think Zaps are effective? What makes them different from other forms of protest?

In 1987, 600,000 gay activists held a weeklong conference in Washington, D.C. By this time, over 41,000 people had died of AIDS. Non-gay leaders, such as the Reverend Jesse Jackson and Cesar Chavez, spoke at the conference, demonstrating the universal concern of AIDS. According to D’Emilio & Freedman (2012):

On Sunday, after an emotional unveiling of almost two thousand panels of the Names Project, a memorial quilt to those who died of AIDS, over half a million marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, past the White House, and toward the Capitol Building, in support of federal antidiscrimination legislation and a more concerted national response to AIDS. (p. 359)

Video: First Unveiling AIDS Quilt 1987

Video: AIDS Memorial Quilt x Gilead: Honoring the Largest Living Memorial Project in the World

Website: The AIDS Memorial Quilt- Interactive

Discussion Questions

- What is the historical significance of the AIDS quilt, and how did it originate?

- How has the AIDS quilt evolved since its inception in 1987, and what does it represent today?

- What are the processes and criteria for adding a panel to the AIDS quilt?

- In what ways has the AIDS quilt served as a form of activism and awareness for the AIDS epidemic?

The United States government, led by the Reagan administration, was almost absent during the early years of the AIDS epidemic (Bronski, 2011). According to Faderman (2015):

Reagan himself would not even utter the word AIDS until his good friend from Hollywood days, Rock Hudson, died of it in 1985. The year before, however, when three hundred thousand Americans had already been diagnosed with the disease, and Ronald Reagan was running for reelection, he told a group that kept tally of a presidential biblical scorecard that his administration would continue to resist all attempts to obtain any government endorsement of homosexuality. That seemed to include any effort to help save homosexual lives. (p. 418)

In a speech at the Third International Conference on AIDS on May 31st, 1987, President Reagan finally acknowledged the AIDS epidemic that had decimated the gay community. By that point, over 40,849 American deaths had been attributed to AIDS (Bronski, 2011; Faderman, 2015).

Video: Reagan Administration’s Chilling Response to the AIDS Crisis

Discussion Questions

- How did the silence and inaction of the Reagan administration in the early years of the AIDS epidemic affect the outcome of the crisis? How did it impact the spread and severity of the disease?

- How did funding decisions during the Reagan administration impact research, prevention, and treatment efforts for AIDS?

- How did political and social attitudes of the 1980s influence the Reagan administration’s handling of the AIDS epidemic?

- How has Reagan’s handling of the AIDS crisis been viewed in historical hindsight, and what lessons have been learned for public health policy?

- Compare and contrast the AIDS crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACT Up activists, alongside members of the National Gay Rights Advocates, declared October 11, 1988 to be the first National Coming Out Day in the United States. On the National First Coming Out Day, ACT UP activists, in front of the FDA headquarters, laid down on the lawns with cardboard tombstones with statements such as “Killed by the FDA” and wearing shirts that read “We Die and They Do Nothing” (Faderman, 2015, p. 431). ACT Up activists alerted every major media outlet about their upcoming National Coming Out Day celebration; their protest received international media coverage.

ACT UP activists held their National Coming Out Day celebration in front of the FDA offices in Maryland. The organization had a long-standing issue with the way the FDA was conducting AIDS medication trials. At the time, the FDA was using the same standard protocols for AIDS medications as it used for nasal sprays. The FDA’s use of their standard protocols meant clinical trials would take 5 to 10 years, and 50 percent of trial participants would receive a placebo. ACT UP believed that the FDA, by using their standard protocols on potentially lifesaving AIDS medications, was allowing gay people to die (Faderman, 2015).

A small group of ACT UP activists, including Peter Staley and Mark Harrington, were frustrated by the handling of the AIDS crisis and did not trust the United States government, the FDA, or the medical community to learn about AIDS. Thus, they formed the Treatment and Data Committee of ACT UP (Faderman, 2015). The members of the Committee were:

much more knowledgeable about AIDS than most doctors, who’d had neither the time nor the inclination to study the disease. To share what they’d learned, they published a comprehensive Glossary of AIDS, Drug Trials, Testing, and Treatment. They also put together a National AIDS Treatment Research Agenda that discussed, clearly and knowledgeably, past problems with AIDS drugs and treatments. (Faderman, 2015, pp. 436-437)

The Committee’s Research Agenda featured a list of 30 promising medications that needed to be expedited through clinical trials. The Committee provided copies of its Research Agenda to the FDA and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) but received no response.

Video: The Life-Saving Legacy of HIV/AIDS Activist Peter Staley

Discussion Questions

- In what ways did Peter Staley’s work with ACT UP change public perception and policy around AIDS in the United States?

- In what ways did Peter Staley’s activism intersect with other social and political movements of the 1980s and 1990s?

- Discuss how Peter Staley advocated for and impacted the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

- What are some of the critical lessons from Peter Staley’s activism that can be applied to current public health crises or social justice movements?

In 1990, ACT Up activists tired of the plateaued progress of medications and the absence of a committed response from the FDA. They began to target the NIH and Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief officer of the NIH’s Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. ACT Up targeted Fauci because of his influence over what medications were tested and what protocols were used. Additionally, his name was well known to the Committee members as Fauci had been actively publishing on AIDS (Faderman, 2015).

On May 21, 1990, ACT Up activists from across the United States gathered at the NIH campus and set off smoke bombs while yelling, “Fauci, you’re killing us” and “the whole world is watching, Fauci” (Faderman, 2015, p. 438). The NIH’s campus police arrived on the scene intending to remove the ACT UP activists from the NIH campus. However, Fauci intervened and asked the NIH campus police to escort the ACT UP leaders to a conference room to meet.

Members of the Committee, including Staley and Harrington, lectured Fauci on the FDA’s inappropriate testing protocols “in the midst of a plague” (Faderman, 2015, p. 438). Staley—who was HIV positive—told Fauci that those who were positive did not have time to wait for the FDA’s clinical trials, and that the practice of using placebos in those trials was unethical. Fauci was impressed by the Committee members’ knowledge and the data they had gathered. Following their meeting, Fauci reported back to his NIH colleagues:

These guys are extremely valuable. They can give us input into how to design the trials and the kinds of needs they see in their community. We have to listen to them. How can we work in partnership with them? (Faderman, 2015, p. 439)

The ACT UP Committee members meeting with Fauci changed the culture at the NIH. Their partnership:

brought about major changes in how the federal government tests and distributes experimental drugs, beginning with the Accelerated Approval process that the Treatment and Data Committee demanded. As a result of that partnership NIH advisory committees and counsels always include activists from communities that are directly affected by NIH’s policy decisions. ACT Up changed America’s scientific culture to profit everyone. (Faderman, 2015, p. 439)

Video: How Dr. Fauci handled the AIDS crisis

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the relationship between Dr. Fauci and AIDS activists, including moments of both conflict and collaboration. How did these interactions shape AIDS research and policy?

- How did Dr. Fauci balance his roles as a researcher, public health official, and policy advisor during the AIDS crisis?

- What criticisms did Dr. Fauci face from the scientific community and AIDS activists, and how did he respond to these critiques? Do you think Dr. Fauci handled the AIDS crisis well? Why or why not?

- Compare and contrast the public health responses to the AIDS crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic under Dr. Fauci’s leadership. What lessons from the AIDS crisis were applied to the handling of COVID-19?

By 1986, “the emotions felt by many in the LGBT community shifted from despair to rage” (Garrettson, 2018, p. 88). Gay activist organizations such as ACT UP channeled the community’s anger toward constructive action, focusing it on media figures and government authorities who downplayed or dismissed the AIDS crisis. (Garretson, 2018). During the AIDS movement, gay activists forever changed their community’s perception of the government, the media, and—most importantly—themselves (Bronski, 2011; Garretson, 2018). One of those changes was the “development of a gay and lesbian community that took considerable pride in its identity” (Garretson, 2018, p. 96), which would consequently change how the gay community would advocate for their rights in the years to come.

In 2013, Peter Staley, a central figure in the AIDS movement, stated, “We’re so caught up in the giddiness of the marriage-equality movement that we’ve abandoned the collective fight against HIV and AIDS” (Signorile, 2015, p. 41). Even as this text is written, HIV and AIDS are not controlled or eradicated. According to the World Health Organization (2023), HIV and AIDS continue to be global healthcare concerns. According to the World Health Organization, 40.4 million people globally have died from HIV/AIDS as of 2023—in 2022 alone, 630,000 people globally died from HIV-related causes. In 2021, 36,136 Americans received a new diagnosis of HIV, with a total of 1.2 million living with HIV in the United States (AIDS Foundation of Chicago, n.d.).

Video: LGBTQ+ Rights Movement and the AIDS Epidemic

Discussion Questions

- How do the LGBTGEQIAP+ rights movement and the AIDS epidemic impact and inform each other?

- Compare and contrast the LGBTGEQIAP+ rights movement with the civil rights movement of Black Americans. What social justice issues were/are present in both movements?

Conservative Backlash

AIDS was an ideal excuse for some conservatives to increase their level of hate speech towards the gay community. In 1990, conservative Republican Pat Buchanan wrote, “AIDS is nature’s retribution for violating the laws of nature” (Bronski, 2011, p. 226). That same year, Jerry Falwell, a conservative Christian televangelist, stated, “AIDS is not just God’s punishment for homosexuals. It is God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals” (Bronski, 2011, p. 226). The American Family Association, a conservative organization, sent letters to fund their campaign to quarantine gay people with the following message:

Since AIDS is transmitted primarily by perverse homosexuals, your name on my national petition to quarantine all homosexual establishments is crucial to your family’s health and security…These disease carrying deviants wander the street unconcerned, possibly making you their next victim. What else can you expect from sex-crazed degenerates but selfishness? (Bronski, 2011, pp. 226-227)

Until 2015, the FDA banned gay and bisexual men, along with transgender women who have sex with men, from donating blood. In December 2015, the FDA removed the lifetime ban and changed their restrictions to allow gay and bisexual men to provide blood donations one year post sexual activity. Nevertheless, it was not until May 11, 2023 that the FDA finally removed their discriminatory restrictions for blood donations that specifically targeted gay and bisexual men (Human Rights Campaign, n.d.). However, according to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (2023),

All prospective donors who report having a new sexual partner, or more than one sexual partner in the past three months, and anal sex in the past three months, would be deferred to reduce the likelihood of donations by individuals with new or recent HIV infection who may be in the window period for detection of HIV by nucleic acid testing. (para. 5)

Legal and Political Social Justice Movements

By the 1990s, many gay rights activists had changed strategies: their focus was on changing specific anti-gay laws and expanding gay rights through legal and political means (Issenberg, 2021). Two primary issues, marriage equality and gay people’s right to serve in the United States military dominated mainstream gay activism in the 1990s and 2000s. Both issues were fodder for politics, and both required change on a national level. Large-scale gay rights organizations, such as the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) and the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund (Lambda Legal), lobbied politicians—whereas private organizations, such as the Gill Foundation, funded campaigns (Issenberg, 2021). This next section details the fight for gay people’s right to marry and to serve in the United States military.

Marriage-Equality Movement

Historically, in the United States, marriage was assumed to be a heterosexual union. In fact, it was not only assumed to be a heterosexual union; there was precedent in court cases that defined it as such. The heterosexual norm of marriage was so strong that before A, the notion of a same-sex couple entering into state-sanctioned marriage seemed culturally and legally implausible” (Eskridge, 1993, p. 1423).

Marriage has historically included specific financial, legal, and medical benefits and protections in the United States. Tax laws regarding inheritance, beneficiary rights of medical insurance and pensions, the ability to adopt a child, parental rights, and next of kin rights were limited to heterosexual marriage (Deitrich, 1994). Limiting those benefits and protections to only heterosexual marriage discriminated against anyone who was not heterosexual.

Although not all gay individuals sought marriage equality in the 1980s, many gay activists discovered that marriage inequality had widespread detrimental effects on the gay community during the AIDS crisis. During the AIDS crisis, gay people were denied marriage benefits and protections, such as the ability to make medical decisions for their partners, inherit shared property, and retain custody of their children (Hagai & Crosby, 2016). Post-AIDS crisis, marriage equality was an important cause for many in the gay community. Not only did the financial, legal, and medical benefits make marriage appealing, but marriage equality signified acceptance, which was critical for many in the gay community. According to Duberman (2018),

Gays wanted in-wanted to hear, after all the suffering they’d been through that they were ‘OK’, wanted their unions officially sanctified, wanted public announcements posted on church doors declaring them decent human beings-not obscene sex maniacs-worthy of membership in the great American mainstream. (pp. 65-66)

Acknowledgment and validation of same-gender marriages would shift gay people’s status from perpetual outsiders to insiders (Eskridge, 1993). Ultimately, “by denying gay and lesbian couples access to the sacred union, society proclaims them less worthy, less committed, insignificant” (Dietrich, 1994, p. 122).

Marriage Equality in Court

In the United States, the legal institution of marriage was left to individual states to decide. State laws, including those regarding marriage, must “pass constitutional muster” (Dietrich, 1994, p. 125). This means that any state law must meet the criteria set by the United States Constitution (Dietrich, 1994; Eskridge, 1993). Historically, the United States Supreme Court has used two clauses of the 14th Amendment, the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause, to uphold and overturn marriage laws in individual states. For example, in the 1967 case of Loving v. Virginia, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Virginia law that prohibited marriage between “a white person and a colored person” was unconstitutional, because it violated both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment (Dietrich, 1994, p. 127).

Video: The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: A History

Discussion Questions

- Before watching this video, what was your understanding of the historical context in which the 14th Amendment was ratified? How did the social and political climate of the Reconstruction era influence its creation?

- What role does the 14th Amendment play in contemporary civil rights issues, such as voting rights, police reform, and anti-discrimination laws?

- How does the public understand the 14th Amendment compared to its actual legal and historical significance? What factors contribute to any gaps in understanding? How might these gaps impact the LGBTGEQIAP community?

By the 1990s, cases on gay equality had been both won and lost in the United States. However, legal cases regarding marriage equality, except for issues of race, had been lost. For example, in 1973, two women sued the state of Kentucky because their application for a marriage license was denied. The women lost their case, Jones v. Hallahan, because a Kentucky court used three dictionaries to conclude that marriage had “traditionally been defined as a union of a man and a woman” (Dietrich, 1994, p. 134).

On December 17, 1990, six same-gender couples went to Honolulu’s Department of Health office and applied for marriage licenses; their applications were denied. The six couples sued the State of Hawaii arguing that because Hawaii’s state constitution guaranteed all couples the right to marry: thus, it was unconstitutional to deny same-gender couples the right to marry. The case Baehr v. Lewin further intensified the fight for marriage equality in the United States (Issenberg, 2021). On May 7, 1993, the Supreme Court of Hawaii ruled in favor of Baehr (Faderman, 2015). The ruling was “the first time that any court on earth had acknowledged that a fundamental right to marriage could extend to gay couples” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 89). Although Baehr v. Lewin was a landmark win, it did not guarantee marriage equality in Hawaii or elsewhere in the United States.

Defense of Marriage Act

Conservatives across the United States feared that “if gay and lesbian marriage is legitimized in any state, other states would be forced to recognize gay marriages conducted in that state through the full faith and credit clause of the Constitution” (Dietrich, 1994, p. 146). After the Baehr v. Lewin ruling, other states enacted laws to prevent potential marriage equality cases (Issenberg, 2021). On February 2, 1995, South Dakota passed Bill 1184, which stated “that any marriage between persons of the same gender is null and void” (Faderman, 2015, p. 587). In March of 1995, both Alaska and Utah passed similar bills, and by 1996, 37 states had either passed bills denying marriage equality to same-sex couples or were in the process of doing so.

In 1996, conservative Congress members introduced the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) to bolster states’ rights further. “DOMA was Congress’ way of anticipatorily retrofitting the U.S. Code to withstand an orchestrated legal assault by homosexuals seeking access to the array of benefits, rights, and privileges its provisions make available to heterosexuals” (Koppelman, 2004, p. 2684). DOMA granted individual states the right “to ignore same-sex marriages contracted in other states” (Ruskay-Kidd, 1997, p. 1435) and created a federal definition of marriage that excluded same-gender couples—later applied to all federal programs and statutes. On September 21, 1996, President Clinton signed DOMA into law (Issenberg, 2021; Ruskay-Kidd, 1997).

Civil Unions

On April 26, 2000, Vermont enacted H.847, designed as a bill for civil unions (Issenberg, 2021). H.847 recognized domestic partnership as an equivalent structure to marriage. For Vermont politicians, H.847 was a compromise to appease the gay community and conservatives, providing many of the same benefits and protections of marriage without impeding on the sacred institution of marriage. “Vermont’s legislature had created a legal classification that existed in no other jurisdiction in the world” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 298), though for many gay activists, H.847 was a loss. Domestic partnerships, although similar, were not tantamount to marriage.

The passing of Vermont’s H.847 drew scrutiny from conservatives across the United States. “In various corners of the American right, political and legal strategists were already plotting whether to amend the U.S. Constitution—for the first time in a generation—to preempt…states from deviating from the historical definition of marriage” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 319). Conservatives no longer felt that a federal law such as DOMA was enough to protect heterosexual marriage. Groups such as the Institute for Family Values, the Alliance Defense Fund, and the Marriage Law Project actively worked to prohibit marriage equality efforts.

The late 1990s and early 2000s brought change to the American public’s exposure to the gay community in popular culture. Brides magazine published an article on same-gender unions, and shows such as Will & Grace and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy were prominent television series (Issenberg, 2021). Nevertheless, opposition to same-gender marriage was still high. According to Issenberg,

To the nongay world, and even within the less politically conscious corners of the gay and lesbian community, reaching for…the gold ring of marriage—especially as states remained within their power to outlaw gay sex between consenting adults—seemed so audacious as to mark any proponent as radical. (p. 392)

Marriage equality activists identified specific states with gay rights issues on their legislative agenda that a targeted campaign could impact. California was one of those states. In 2005, the Let California Ring project (the Project), supported by the HRC and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, was launched. The Project was a strategy for gay rights activists. “Never before had a gay-rights organization attempted to shift public opinion around same-sex unions in the absence of immediate political or legal action” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 465). The Project’s public goal was to spark millions of conversations, while the practical goals were to increase public support for same-gender marriage by a minimum of two percentage points and to increase the number of supporters by 400,000.

Video: Let California Ring Campaign – Change Hearts and Minds

Discussion Questions

- Do you think Let California Ring was successful? Why or why not?

- Is this kind of advocacy manipulative or strategic? Discuss.

Freedom to Marry

During the first decade of the 2000s, gay rights activists were losing the fight for marriage equality, both in court and with voters. By 2009, “thirty states had imposed constitutional amendments restricting marriage to heterosexual couples, and the majority of those amendments also blocked civil unions, domestic partnerships, or other recognition of same-sex relationships” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 533). Many opponents of marriage equality were in particular religious communities. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, evangelical Christians, and the Roman Catholic Church had immense power and resources to fight against marriage equality.

However, support for marriage equality shifted by 2012. Private donations from people as varied as Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Brad Pitt contributed to marriage equality. Additionally, for the first time since President Clinton, the United States had a gay-friendly president, Barack Obama (Issenberg, 2021). During Obama’s campaign, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) had been a straightforward issue—marriage equality was not. “As a candidate, Obama received few signals that marriage rights were a policy priority within the gay community, or liberal activists more broadly” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 636). From the beginning of his presidency, Obama made it clear he did not support DOMA, as he believed it to be a discriminatory policy and that it interfered with states’ rights. Obama was not alone—by 2012, 120 Democrats in Congress co-sponsored the repeal of DOMA.

That said, Obama did not express explicit support for marriage equality. “For a decade he had been a gradualist on marriage, as a matter of principle and political contrivance” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 686). However, others surrounding Obama were ready to support marriage equality. In March 2012, Vice President Joe Biden supported marriage equality. During an interview for Meet the Press, Biden stated,

The good news is that, as more and more Americans come to understand, what this is all about is a simple proposition: Who do you love and will you be loyal to the person you love? …And that’s what people are finding out is what all marriages at their root are about, whether their marriage is of lesbians or gay men or heterosexuals. (Issenberg, 2021, p. 693)

Obama stated many times that his view on same-gender marriage was evolving—by 2012, it had become one of support. On May 9, 2012, during an interview with Robin Roberts, President Obama became the first sitting president to state that he believed same-sex couples should be able to get married. This was an incredible risk for a president who was considered an underdog during his reelection campaign (Issenberg, 2021).

Video: President Obama – Gay Marriage: Gay Couples ‘Should Be Able to Get Married’

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think it took so long for Obama to speak out for gay marriage?

- What were the political and social ramifications of Obama speaking out in support of gay marriage?

The Supreme Court

The fight for marriage equality in the United States has been punctuated by several landmark cases that have significantly impacted the rights of same-sex couples. Most cases were fought in individual states, as the United States Supreme Court chose not to hear arguments on same-sex marriage; in the early 2000s, that changed. The United States Supreme Court decided to engage in two cases, Windsor v. The United States and Obergefell v. Hodges. Ultimately, both changed the definition of marriage in the United States (Issenberg, 2021).

In 2007, Thea Spyer–who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1977–was told that she had less than a year to live. Thea Spyer and Edith Windsor had loved each other and lived together since 1965; they wanted to marry before Thea died. On May 22, 2007, Thea and Edith flew to Ontario, Canada to marry because they could not legally do so in New York. Thea died on February 5, 2009 (Faderman, 2015).

Although New York did not grant same-gender marriages, the state did recognize same-gender marriages performed elsewhere. However, due to DOMA, the federal government did not. Federal law deemed that Edith:

inherited from Spyer half the value of the apartment and little cottage that the two women had shared in the Hamptons. To the federal government, she and Thea Spyer, despite their forty-plus-year history, despite their legal marriage, were no more than strangers to each other. (Faderman, 2015, p. 624)

The United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) levied $363,000 in estate taxes against Edith. Edith, who was 81 years old, had no choice but to pay, which decimated her savings. Edith sued the United States government and won on June 6, 2012. The judge ruled that “section 3 of DOMA violated the plaintiff’s rights of equal protection under the 5th Amendment” (Faderman, 2015, p. 626) and ordered the IRS to refund Edith her money plus interest. The United States government appealed the decision.

In 2012, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in Windsor v. United States, and on June 26, 2013, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Section 3 of DOMA was unconstitutional. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote:

DOMA instructs all federal officials, and indeed all persons with whom same-sex couples interact, including their own children, that their marriage is less worthy than the marriages of others. The differentiation demeans the couple, whose moral and sexual choices the Constitution protects, and whose relationship the State has sought to dignify. And it humiliates tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples. (Issenberg, 2021, pp. 719-720)

The United States Supreme Court, with its ruling in Windsor v. United States, declared that same-gender couples had the rights to

be treated by the IRS as their heterosexual counterparts were treated, but also that they could get social security and veteran’s survivor benefits, they could hold on to their homes when widowed, they could get green cards for an alien spouse, they were eligible for over a thousand other benefits that only straight couples had enjoyed before. (Faderman, 2015, p. 628)

The Windsor v. United States ruling was a considerable victory for marriage equality. Although the ruling did not change states’ rights to decide on other issues regarding same-gender marriages, states’ courts did use the ruling for individual cases. Within 15 months, “an accelerated sequence of federal and state decisions had made same-sex marriage legal in thirty states” (Issenberg, 2021, p. 727).

In 2013, James Obergefell and John Arthur married in Maryland because it was not legal for them to do so in Ohio. John was dying, and he wanted James listed as his surviving spouse on his death certificate. As Ohio did not recognize John and James as legally married, James would not be listed on John’s death certificate. Consequently, James filed a lawsuit, Obergefell v. Hodges, against the state of Ohio.

On December 23, 2013, an Ohio judge ruled in favor of Obergefell. In response, the state of Ohio appealed, and the United States Court of Appeals ruled against Obergefell. James then decided to take his case to the United States Supreme Court. On January 16, 2015, the Court announced that they would hear arguments in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges. On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled in favor of Obergefell; their ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges invalidated state laws that banned same-gender marriage (Issenberg, 2021). Justice Kennedy concluded:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideal of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right. (Murray, p. 1213)

Obergefell v. Hodges was the final case in the fight for marriage equality, but certainly not the only one. In many ways, the fight for marriage equality was hundreds of individual battles across the United States. Large-scale organizations, such as HRC, championed marriage equality, as did individual Americans, lawyers, judges, and politicians.

Video: June 26, 2015: SCOTUS Same Sex Marriage Victory

Video: Love Wins: June 26, 2015, Part 1

Video: The Light of Progress: June 26, 2015, Part 3

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think it took so long for marriage equality to become federal law? What are the issues surrounding it?

- Do some research into marriage in other countries. What kind of same sex marriage laws do they have?

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Elected in 1992, President Bill Clinton was the first prominent political figure in the United States to actively endorse gay rights. Clinton won the gay vote by promising to pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) and to end the ban on gay people serving in the military, which was made illegal under Article 125 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Article 125 identified sodomy as a crime (Faderman, 2015). “There’s no question that Clinton made his promise to gays and lesbians in good faith. As soon as he took office, he was ready to grab the pen and sign the executive order” (Faderman, 2015, p. 499).

Unfortunately for the gay community, Clinton had overestimated his power and the support of others in the government. Congress—particularly Senator Sam Nunn—was determined to stop any integration of gay people into the military. Clinton faced opposition from some members of Congress and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who refused to support Clinton in ending the ban. General Colin Powell, along with other military leaders, was against gays in the military because he believed that they would be “distracting and destroy fighting readiness; they’d be divisive and would destroy unit cohesion and morale” (Faderman, 2015, p. 499).

Lastly, the Christian right mobilized to stop gay people from being in the military. Christians besieged congressional offices with thousands of letters requesting that the military ban remain in place. “During eight days in early February, soon after Clinton announced his intention to keep his promise to lesbians and gays, the Capitol switchboard logged 1,650,143 calls, mostly from people saying that his plan endangered the country” (Faderman, 2015, p. 500).

On March 29, 1993, the Senate Armed Services Committee began hearings to consider the matter—these hearings were “a disaster” (Faderman, 2015, p. 504). By the end, it was clear that Clinton would have to compromise. Ultimately, the two parties settled on the policy of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT), which went into effect on July 19, 1993.

DADT allowed for gay people in the military if they did not speak about being gay or “get caught acting (or seeking to act) on it, on or off base” (Faderman, 2015, p. 504). Although Clinton tried to present DADT as “an honorable compromise” (Faderman, 2015, p. 504), the gay community was infuriated. DADT represented the idea that to be gay was wrong.

Ultimately, DADT did not work. In its time, over 14,000 gay service members were discharged after the military found them out. In 2001 alone, 1,273 service members were discharged under DADT. In its annual reports, the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network revealed that the persecution of gay service members had “gotten worse because the policy had ‘stirred up a hornet’s nest’ of homophobia” (Faderman, 2015, p. 522). Over $1.3 billion was spent on investigations by the military to find out and justify the discharges of gay service members.

By 2007, views on gay people in the military had shifted in the United States. That year, 28 retired generals and admirals signed a letter to the United States Congress asking them to repeal DADT and allow gay people to serve in the military free of restrictions. In 2008, 104 retired generals and admirals reiterated the same sentiment. By 2009, a Washington Post survey reported that 75 percent of those polled believed that gay people should be allowed to openly serve in the military. That same year, General Colin Powell, who had been adamantly against lifting the ban against gay people in the military, changed his mind and stated, “it was time to reconsider the old policy” (Faderman, 2015, p. 512).

In 2009, President Obama resumed the fight that President Clinton had begun. Obama told members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,

I think Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is wrong. So, I want you guys to understand that I want to work with the Pentagon, I want to figure out how to do this right, but I intend to repeal this policy. (Faderman, 2015, p. 514)

Almost immediately, Obama faced resistance; he agreed that he would allow Congress to be responsible for repealing the DADT.

During Obama’s first year as president, another 428 gay military service members were discharged under DADT. “There’s no doubt that Barack Obama genuinely wanted a military that was open to anyone willing and able to serve; yet he feared weakening his presidency” (Faderman, 2015, p. 517). In 2010, during his first State of the Union Address, Obama again stated his intention to repeal DADT.

Gay activists and community members were tired of waiting for Congress to decide to repeal DADT. Therefore, they went directly to the American public. Retired Admiral Alan Steinman, retired Brigadier General Virgil Richard, and retired Brigadier General Keith Kerr volunteered to have “a grand coming out” (Faderman, 2015, p. ) in a New York Times article detailing their experiences as gay men being forced to lie about their identity while serving their country. The Call to Duty Tour:

brought together young gay and lesbian vets and sent them out, especially to the red states, to tell their stories about how they’d served with devotion and faultless records and had been discharged only because they were gay, or had left before being kicked out because the stresses and strains or hiding were intolerable (Faderman, 2015, p. 524).

Some organizations, such as the Human Rights Campaign’s Voices of Honor, followed the Call to Duty Tour’s lead. Other organizations, such as Get Equal, took a more radical approach. Get Equal, founded by Robin McGehee and Kip Williams, engaged in activities reminiscent of ACT UP’s effective Zaps (Faderman, 2015). On March 18, 2010, Get Equal members Dan Choi and James Pietrangelo, who had been discharged under DADT, allowed themselves to be chained to the White House fence by McGehee. Choi, Pietrangelo, and McGehee were arrested and fined. In both April and May of 2010, Get Equal members once again Zapped the White House by chaining themselves to a fence.

Meanwhile, the government sent surveys to 400,000 active and reserve service members and 150,000 military spouses to solicit their feelings about openly gay military service members. “More than 70 percent of respondents said the effect of repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell would be positive, mixed, or nonexistent” (Faderman, 2015, p. 529). Cumulatively, 92 percent of active service members reported that the effect of having openly gay service members would have a very good, good, or neutral impact on unit cohesion.