8 Being a Woman in the United States

Nikki Golden and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will understand the history of women’s activism in the United States.

- The reader will identify the progression of women’s rights in the United States.

- The reader will connect the women’s rights movement to current social justice movements.

Being a woman in the United States of America is complex. American women are not monolithic in identity. They differ by ability, age, generation, geography, opportunity, race, relationship status, religion, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation. Griffith (2022) states, “It’s a risk to categorize or generalize because real people have multiple and individual identities” (p.xv). Recognizing this complexity when discussing women is an essential task of this chapter, as the experiences of American women throughout history have varied through their intersecting sociocultural identities.

This chapter starts with a brief history of Indigenous women before European colonization. It progresses chronologically through the women’s rights movement, women’s suffrage, and the various legislation and policies that impact women in the United States. There are entire books on women’s history; thus, the choices about what to include in this chapter were complex and nuanced. These choices are intended to give an overview of the experience of being a woman in the United States throughout history, and to connect that experience to current events and social justice movements.

Activity 8.1 – Digging Deeper: Language Matters

What is the difference between the terms woman and female? Female is an assigned label given to those who are born with a visible vulva. Woman (or girl) is a sociocultural term denoting a gender identity. The gender identity of a woman (or girl) includes internal and external experience, expression, and role. For example, a duck can be female, but it cannot be a woman. In general, we will use the term woman in this text to denote a more holistic definition of the gender identity of being a woman.

Discussion Questions:

- What are the key differences between the terms woman and female? How do these differences impact our understanding of gender identity?

- How might the distinction between female and woman influence discussions about gender equality and women’s rights?

- How do internal and external experiences, expressions, and roles contribute to the gender identity of a woman? Can you provide examples of these internal and external factors?

- In what ways do societal and cultural factors shape the gender identity of a woman? How might these factors differ across cultures or historical periods?

Indigenous Women

From first contact, the Indigenous people’s ways of expressing gender confounded European explorers and colonists. In Europe, gender and gender expression was defined within a patriarchal hierarchy, and European women had little to no power in private or public spheres. In contrast, many Indigenous women had power in both. Numerous Indigenous communities, such as the Cherokee, Iroquois, and Muscogee, were matriarchal in lineage, and children inherited their social status from their mothers (Faderman, 2022; Hämäläinen, 2022). In addition, it was often the Indigenous women that engaged with the European colonists. Indigenous women often understood the value of learning to read, speak, and write the colonists’ languages, and would allow missionaries and priests to teach them to do so under the guise of religious conversion (Hämäläinen, 2022).

In some Indigenous communities, women participated in leadership roles and decided on consequences for captives (Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014; Zinn, 2003). For example, the Cherokee people engaged in inclusive decision-making, and Cherokee women held important advising roles in the tribe. Even when pregnant, some Cherokee women participated in battle and were known as “war women” (Hämäläinen, 2022, p. 198).

Many unmarried Indigenous women made autonomous decisions, including who they would and would not marry. If they no longer wanted to be with their husband, Indigenous women would put the man’s belongings outside of their dwelling to signal that their relationship was over (Blackhawk, 2023).

Website: How Native American Women Inspired the Women’s Rights Movement

Discussion Questions:

- Describe how Indigenous marriage and divorce practices differed from those of European colonists. Why might the European colonists have felt threatened by this practice?

- How does the autonomy of Indigenous women in marriage decisions challenge or support modern feminist movements advocating for women’s rights and gender equality? What parallels can be drawn between historical and contemporary struggles for women’s autonomy?

- How might the practices of Indigenous women regarding marriage influence current discussions on the intersection of cultural traditions and women’s rights? What balance should be struck between respecting cultural traditions and promoting universal women’s rights?

- What lessons can contemporary societies learn from Indigenous women’s practices in supporting and promoting women’s rights and autonomy? How can these lessons be applied to improve gender equality and women’s empowerment today?

Indigenous women entered the 18th century with positions of power, privilege, and respect. However, their positions were lost by the end of that same century due to European colonization and Christian conversion. Christian missionaries insisted that the equitable privilege Indigenous women experienced was sinful. As the United States expanded its territory westward, Indigenous women were expected to conform to the White European norms of womanhood. As a result, “they became as powerless as their White counterparts” (Faderman, 2022, p. 42).

Many Iroquois women had immense power within their communities. They chose the war chiefs, were heard first in community debates, and decided the fates of their enemies. Iroquois women proposed marriage and, at times, would take more than one husband. Iroquois matriarchs owned crops and homes, and controlled the wealth of their families (Faderman, 2022).

Discussion Questions

- How do you think the Iroquois and other Indigenous women influenced female European colonists?

- How do you think the Iroquois and other Indigenous women influenced male European colonists?

- Faderman (2022) states that colonists interpreted Indigenous women’s equitable status as dominant and domineering behavior. How might this perception have influenced stereotypes about women today?

The Women’s Rights Movement: The First Wave (1848-1920s)

The first wave of the women’s rights movement began in the 19th century and continued throughout the early part of the 20th century. It included the women’s suffrage movement as well as fights for higher education, equal citizenship, and reproductive rights for women (Lepore, 2018). This first wave coincided with westward expansion, the continued genocide of Indigenous people, slavery, the Civil War, industrialization, and World War I.

During the first wave of the women’s rights movement, women in the United States did not have the same power, privileges, or rights as men. Women were not allowed to vote, pursue education without permission, or, at times, choose their clothing. Married women were not allowed to inherit or own property, bring legal proceedings to court, run a business, divorce, or maintain custody of their children (Gallagher, 2021). According to Catt and Shuler (2020), the “legal existence of the wife was so merged in that of her husband that she was said to be dead in law” (p. 4).

The founders of the women’s rights movement have often been stereotyped as White, middle-class, educated, and spinsters. While some fit those categories, women involved in the first wave were also Asian, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx. “For many Native American, Hispanic, Black, and Asian women political activism first and foremost meant ensuring their families survival in the systemic racism that menaced them” (Gallagher, 2021, p. xii). Some women were married, some lived in poverty, some were denied education, and some were part of the LGBTGEQIAP+ community.

Seneca Falls

In the late 1800s, most women understood that they did not have the same privileges and rights as men. Many women had been active in other social justice movements such as abolition and had learned to organize, raise money, and engage in public speaking (Griffith, 2022). As a result, some women individually railed against these inequities. However, they saw little sustainable change. In 1840, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton attended the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London. On the Convention’s first day, male delegates voted to ban women from participating. Mott and Stanton, who had not met before this event, “were thoroughly aroused by this experience” and “agreed to call a convention upon their return to the United States, to be devoted exclusively to the Rights of Women” (Catt & Shuler, 2020, p. 15). This was the beginning of the organized women’s rights movement in the United States.

It took Mott and Stanton eight years, but on July 19, 1848, the first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Mott and Stanton led the convention to launch the women’s rights movement in the United States (Catt & Shuler, 2000). During its course, Stanton wrote and read the Declaration of Sentiments. This declaration was intentionally based on the Declaration of Independence. It was intended “to dramatize the denied citizenship claims of elite women during a period when the early republic’s founding documents privileged white propertied males” (National Park Service, n.d., para 4). The Women’s Rights Convention was so well attended that a second convention was held two weeks later in Rochester, New York (Catt & Shuler, 2020). The two conventions gained national attention and sparked the women’s movement across the United States.

Video: What Happened at the Seneca Falls Convention?

Discussion Questions:

- In what ways did the Seneca Falls Convention challenge the existing social and legal structures that oppressed women? What impact did it have on these structures?

- How did the women’s rights convention contribute to the fight for women’s rights and for social justice?

- How did the women’s rights convention address issues of intersectionality, particularly the struggles faced by women of different races, classes, and backgrounds?

- What parallels can be drawn between the Women’s Rights Convention and contemporary social justice movements? What can modern-day social justice movements learn from the strategies and approaches used by the convention?

Read through the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and M.J. Cage as shared by the National Women’s History Museum

Discussion Questions:

- What were the main grievances listed in the Declaration of Sentiments, and how did they reflect the social and political context of the time?

- How did the Declaration of Sentiments frame the concept of women’s rights, and what key demands did it make for achieving gender equality? Which of these demands have been addressed over time, and which are still relevant today?

- What was the significance of the Declaration of Sentiments being modeled after the Declaration of Independence, and how did this influence its impact? How did this framing help to legitimize the demands for women’s rights?

- How might the principles outlined in the Declaration of Sentiments be applied to current issues facing women and marginalized groups? What modern issues could benefit from a similar approach to advocacy and reform?

Social Justice Movements

After the successes at Seneca Falls and Rochester, local women’s suffrage societies were formed across the United States as women began to work in specific social justice movements. According to Catt and Shuler (2020),

Encouraged by the knowledge that other women were rising, organized groups sprang into being in all parts of the country with no other incentive than the ripeness of the time, and no other connection with the original movers than the announcements of the press. (p. 18)

While women participated in the suffrage movement, they also participated in many other social justice movements, including the social morality movement, the anti-slavery movement, and the labor reform movement.

Social Morality Movement

Starting in the late 19th century, White middle- and upper-class women in the United States began to be lauded as the moral “soul of the new nation” (Faderman, 2022, p. 87). During that time, women believed it was their responsibility to teach men to be good and moral. This cultural shift gave women a new sense of empowerment. Previously, women had been placed in a position inferior to men. Now, women were seen as morally superior to men. Women took this role seriously and were ready to fight for the morality of the United States. The two most prevalent issues that women took a stand on during this time were prostitution and drunkenness (Faderman, 2022).

Prior to the early 1800s, many in the United States viewed prostitution as “a necessary evil” (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012, p. 140). By the 1850s, it was estimated there were over six thousand prostitutes in New York City alone. However, as the social morality movement took hold, the American public was no longer willing to accept prostitution as necessary (Faderman, 2022; Lepore, 2018). Women, in particular, had genuine reason to despise prostitution because “[it] made a mockery of the widely cherished notion of women’s innate modesty and purity” (Faderman, 2022, p. 89).

The evangelical revivalist movement, the Second Great Awakening, increased women’s fervor for eradicating prostitution. Some evangelical women blamed men for being the “deliberate destroyers of female innocence” (Faderman, 2022, p. 92). These evangelical women, as well as others, established organizations to fight prostitution and to save women forced to prostitute. For example, Hetty Reckless, a free Black woman, established the Moral Reform Retreat, which focused on assisting free Black women who were prostitutes. Lydia Finney, an evangelical White woman, established the New York Female Moral Reform Society (NYFMRS), the first national organization of women. NYFMRS had its own journal, the Advocate of Moral Reform, with 17,000 subscribers (Faderman, 2022).

In 1848, New York State passed the first seduction law in the United States. Seduction laws punished men for taking advantage of young women by promising, among other things, marriage, to obtain sex. The New York seduction laws were strongly influenced by the activism of the New York Female Moral Reform Society (NYFMRS). The NYFMRS was concerned about women coming from the countryside to the city to work. The concern was that, without parental supervision, women would be taken advantage of and fall into a life of sin and immorality, ultimately turning to prostitution. Other states followed this precedent and, by 1885, 27 states had seduction laws (Faderman, 2022). Seduction was punishable by up to five years in prison in New York State and up to 20 years in other states. Often, women of color, prostitutes, and women over the age of 37 years were excluded from the protection of the seduction laws (Knox, 2020).

Discussion Questions

- How did the seduction laws of the late 1800s reflect the societal attitudes towards gender and morality of the time? What do these laws say about how society tried to control women’s sexuality?

- In what ways did seduction laws reflect or reinforce existing gender norms and expectations? How did these laws interact with other legal and social structures to regulate women’s behavior?

- How did the exclusion of certain groups from the protections of seduction laws reflect broader patterns of discrimination and marginalization? What do these exclusions reveal about the intersection of gender, race, and socioeconomic status at that time?

Alcohol consumption was also rampant in the United States at this time, and became a focus of the Social Morality Movement. By the 1830s, the annual consumption of hard liquor was over seven gallons per capita. In comparison, the annual consumption in the 21st century is approximately two gallons per capita. Drunkenness, like prostitution, was considered a moral failing of men. Women, as well as some religious leaders, believed alcohol and men’s drunkenness were ruining American families (Faderman, 2022).

For Black women, the issue of drunkenness was not just about family but about their quality of life in the United States. Black women advocated for temperance at the third annual Improvement of Free People of Color convention in 1833, and many Black women believed that if Black men were accused of or engaged in drunkenness, it would impact the social justice movements for equality and respectability in the United States. Many Black women promoted what was referred to as the politics of respectability, which entailed conforming to mainstream norms to gain rights (Faderman, 2022).

Video: Respectability politics subjugate personal authenticity by Sarah Kelsey Hall

Article: “Democracy Limited: The Politics of Respectability” by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Discussion Questions

- What key arguments or themes do the resources present about respectability politics?

- How does respectability politics connect with the women’s rights movement?

- What recommendations do you have for addressing the challenges associated with respectability politics, especially regarding women’s rights? How practical and effective are these recommendations for current social justice efforts?

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), one of the largest national movements in the history of the United States, was a byproduct of the social morality movement (Gallagher, 2021). Established in 1874, the WCTU included Black and White women. Initially established to address the issues of alcohol consumption, the WCTU expanded its mission to become a comprehensive social reform program that included suffrage. The WCTU’s leadership encouraged women to “take up an unusual line of work that forged new vocational paths” (Gallagher, 2021, p. 131), one of which was the new profession of social work.

Video: Women’s Christian Temperance Union

Discussion Questions

- Discuss how the WCTU intersected with women’s rights and women’s safety.

- How did the WCTU influence the women’s rights movement?

Some women, such as Susan B. Anthony, left the social morality movement due to the sexist attitudes and behaviors of men in the movement. However, engagement in the social morality movement provided women with experience in leadership, organizing, and working together to advocate for a cause. The women of the social morality movement learned how to publish newsletters and journals, raise money, and lobby for support—skills that would all prove invaluable for the women’s rights movement (Faderman, 2022; Griffith, 2022).

Anti-Slavery Movement

Slavery has existed in the world for millennia. Throughout history many people viewed slavery as a right or a necessary evil, but there have also been people who viewed slavery as unnecessary and cruel. In the United States and colonial America, those who were anti-slavery were in the vast minority for centuries, and it was not until the late 17th century that the anti-slavery movement gained momentum.

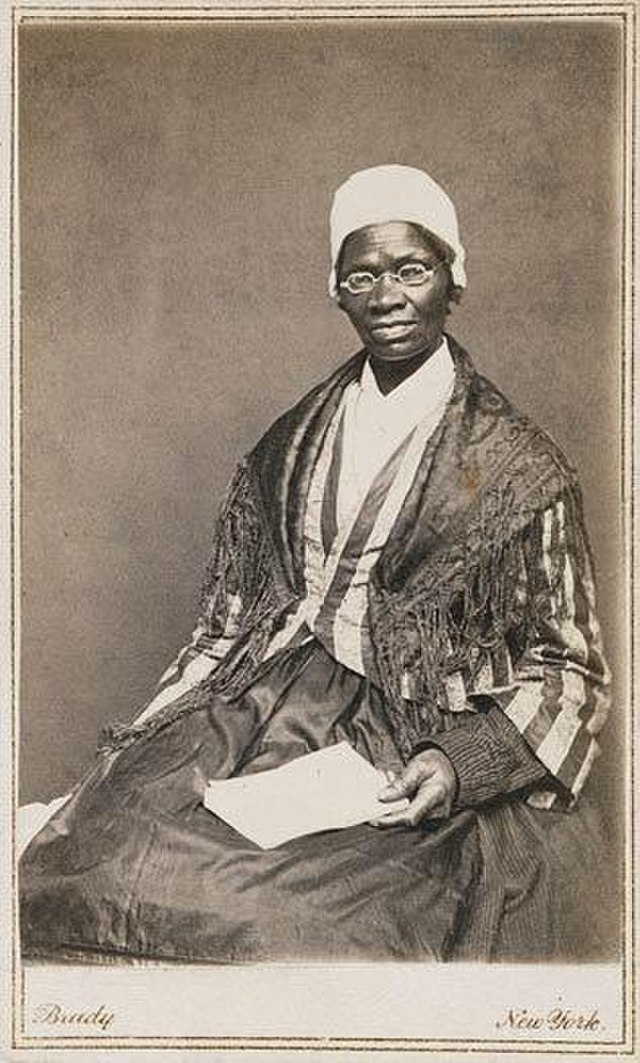

By the early 1800s, societal views on slavery were shifting as “most men and women recognized the incompatibility between America’s founding principle of equality and at least some of its inherited structures” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 77). By the mid-1830s, women’s anti-slavery societies were established across the northeastern areas of the United States. Black women participated in the anti-slavery movement, and former slaves such as Harriet Jacobs and Sojourner Truth shared their lived experiences. Other Black women, such as Nancy Remond, founded formal anti-slavery organizations (Cobbs, 2023; Faderman, 2022). Black women established anti-slavery societies in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, while White women established anti-slavery organizations in cities such as Boston, Cincinnati, and New York (Cobbs, 2023). Many of the women in the anti-slavery movement, such as Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, and Angelina Grimke, were Quakers. Traditionally, Quakers had been anti-slavery throughout the establishment of the American colonies and were later active in the underground railroad movement. Anthony, like many other White women in the anti-slavery movement, began her advocacy work in the social morality movement.

Not everyone welcomed women into the anti-slavery movement. Unlike other movements, women were not encouraged to be active participants or leaders in anti-slavery movements. Reverend Samuel Cornish, a free Black Man, believed if Black women were allowed to participate in the anti-slavery movement, their role should be limited to “raising money to support the activities of the men” and that they “must not pursue masculine views and measures” (Faderman, 2022, p. 108). In response, Maria W. Miller Stewart chastised Black men for not doing enough “to alleviate the woes of [their] brethren in bondage” (Faderman, 2022, p. 110).

After the Civil War, leaders of the anti-slavery movement shifted focus. Some leaders, such as William Lloyd Garrison, felt their work was done after the United States Congress passed the 13th Amendment. Other leaders, like Stanton and Anthony, believed it was time to shift the focus to universal suffrage. In 1866, Stanton and Anthony established the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) to support what they believed was a shared fight for universal suffrage. AERA was an integrated organization and Black women, such as Frances Harper and Sojourner Truth, were members (Faderman, 2022).

Despite the belief that Stanton and Anthony had that others shared their vision for universal suffrage, there continued to be dissension in the anti-slavery movement. Wendell Phillips, the president of the American Anti-Slavery Society, believed the interests of women and Black men needed to be divided to achieve political gains. In an editorial for the National Anti-Slavery Standard, Phillips wrote, “We cannot agree that the enfranchisement of women and enfranchisement of the blacks stand on the same ground or are entitled to equal effort at this moment” (Faderman, 2022, p. 183). Even Fredrick Douglass, a long-time supporter of women’s rights and Anthony’s friend, believed women should step aside so that Black men could attain their rights. During a debate at an AERA meeting, Douglass stated,

When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans, when they are dragged from their houses and hung upon lamp posts…when they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their head…then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own. (Faderman, 2022, p. 183)

Many women, such as Anthony and Stanton, had worked tirelessly in the anti-slavery movement. They were devastated by the growing dissent and perceived statements such as these as a betrayal. Stanton believed that elevating “one oppressed group over another tempted it to abuse others lower on the ladder” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 106). Sojourner Truth stated,

There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and colored women not theirs, the colored men will be masters over women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. (Gallagher, 2021, p. 53)

Some women agreed with Phillips and Douglass. Many Black women, such as Frances Harper, believed that some members of AERA ignored the genuine concerns of race and left the organization (Cobbs, 2023).

The 14th and 15th Amendments

In 1868, Congress passed the 14th Amendment. Its ratification meant that, for the first time, the word “male” was in the United States Constitution. The 14th Amendment granted birthright citizenship to all men born in the United States.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment was ratified, giving all citizens the right to vote. Because the 14th Amendment declared all men as citizens, the 15th Amendment then gave all men the right to vote. “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (U.S. Const. amend. XV). Anthony and Stanton objected to the 14th and 15th Amendments not because they gave voting rights to all men, but because they did not do the same for all women. After four years of arguing that women’s rights were of equal value to men’s, Stanton made a series of divisive statements out of “damaging, white-hot outrage” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 106).

By 1870, the anti-slavery movement was victorious. Emancipation and the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments were clear indications that the anti-slavery movement had been successful. However, not all members of the anti-slavery movement were done fighting for the rights guaranteed to them by the United States Constitution. Women like Anthony and Stanton no longer believed the right to vote would be enough to challenge the systemic patriarchy of the United States. Even with equal rights, these women knew that prejudice against women was still embedded into the fabric of society (Cobbs, 2023).

Labor Reform Movement

By the early 19th century, it was not uncommon for women of lower economic status to contribute to their families’ survival by working for wages. Most often, that work was done inside the home. For example, shop owners provided fabrics for weaving, and women were paid for the work they completed at home. However, with the opening of textile mills, young women moved out of their family homes and worked in the mills (Faderman, 2022).

Working conditions in the textile mills were challenging, and young women complained they were often penalized by having their wages reduced or losing their jobs. In 1834, a group of young women known as the Lowell Girls went on strike to protest a proposed wage reduction. Unfortunately, the strike failed as the young women needed more leverage to win. However, the strike resulted in the establishment of the first working women’s union in the United States, the Factory Girls’ Association (Faderman, 2022).

Video: The Lowell Girls

Discussion Questions:

- What role did the Lowell Girls play in the early labor movement? How did their activism contribute to labor reform and workers’ rights?

- What was the role of the Lowell Girls in the broader context of women’s economic independence and empowerment? How did their work influence perceptions of women’s roles in the economy?

- What is the legacy of the Lowell Girls in terms of labor rights and women’s history? How are their contributions remembered or evident today?

During the early 1900s, “nearly one in five manufacturing jobs in the United States was held by a woman” (Lepore, 2018, p. 380), and many fought for labor protections and rights for women. The National Congress of Mothers, later known as the Parent Teacher Association (PTA), was one of the organizations that advocated for labor protection for women. The National Congress of Mothers wielded such respect that in 1908 Theodore Roosevelt referred to it by stating, “This is one body that I put even ahead of the veterans of the Civil War” (Lepore, 2018, p. 380).

Women, such as Jane Addams and Florence Kelly, led the fight for women’s labor reform, including minimum wage laws, maximum hours worked laws, and child labor laws. Kelly, who had a law degree, noted that the court system treated women differently than men. Due to this, Kelly felt that some protections, such as maximum hour laws, would have a better chance of success if explicitly aimed at women laborers. Kelly argued that because they were physically more fragile than men, women needed special protections in the workplace (Lepore, 2018).

In 1906, Kelly hired attorneys Louis Brandeis and Josephine Goldmark to argue for protecting women laborers in the landmark case Muller v. Oregon. Muller, who owned a laundry business, was convicted of violation of Oregon labor laws because he had made his female employees work over ten hours a day. Muller challenged the conviction and took his case to the Oregon State Supreme Court. The Muller v. Oregon case was, according to Kelly, representative of the need for protection for women laborers across the United States (Lepore, 2018).

Brandeis and Goldmark, who were instrumental in the labor reform movement, built their argument for Muller v. Oregon using other court cases from across the United States. Part of their argument was based on the premise that working long hours “is more disastrous to the health of women than of men and entails upon them more lasting injury” (Lepore, 2018, p. 381). Brandeis and Goldmark were victorious in Muller v. Oregon. The case provided the protections that Kelly wanted for women laborers.

Muller v. Oregon had positive and negative long-lasting effects that could not have been predicted. The most detrimental effect was that it opened the door to decades of gender discrimination in the workplace. Lepore (2018) states that:

These laws rested on the idea that women were dependent, not only on men, but on the state. If women were ever to achieve equal rights, this sizable body of legislation designed to protect women would stand in their way. (p. 382)

One of Muller v. Oregon‘s positive effects was that it created a legal precedent for the use of social science in court cases. This set the stage for the use of social science evidence to prove facts of racial inequality in Brown v. Board of Education.

Between 1909 and 1917, maximum work hours labor laws for women existed in 39 states. By 1923, minimum wage laws for women existed in 15 states and, by 1920, laws that provided financial relief for women through mothers’ and widows’ pensions had been passed in 40 states (Lepore, 2018). Florence Kelly and others worked incredibly hard to get labor laws passed for women. This was a great accomplishment in protecting women who could not protect themselves.

Discussion Questions

- How did mothers’ and widows’ pensions contribute to the financial security of women? In what ways is this a women’s rights issue?

- Did labor laws for women impact every woman the same? Why or why not? Discuss disparities based on intersecting identities.

- What were the long-term effects of the labor laws and pension systems established during this time?

Women’s Rights in the West

During the mid-to-late 1800s, the Western region of the United States was very different from the East and South. White people in the West, including women, had different lifestyles and needs than those in the East and South. In many ways, women’s rights progressed more quickly in the western United States. Women of the West, such as Clarina Nichols and Elizabeth Piper Ensley, fought for women’s rights and, in many cases, won. An excellent example of this was divorce. Because married women could not inherit or own property, they were often destitute after a divorce in many areas of the United States. In addition, divorce was frowned upon in society, and usually, women would lose custody of their children if divorced. However, in the West, divorce was not seen as a stain on a woman’s reputation in the same way. Judges “frequently rewarded the custody of children to mothers rather than father” (Gallagher, 2021, p. 48).

During the Civil War, women in the West gained even more rights. While President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act for political reasons and not to take a stand on women’s rights, the Act allowed women who were heads of households to own property in the Western territories (Gallagher, 2021). “In addition to its economic benefits, the act enabled tens of thousands of women to realize the dream of land ownership that had been bound up with citizenship and status [and] set a powerful precedent for equalizing their legal status” (Gallagher, 2021, p. 50).

Another act, the Morrill Land-Grant Act, was passed within a few months of the Homestead Act. The Morrill Land-Grant Act allowed women to attend tuition-free higher education (Gallagher, 2021). Higher education gave women more choices regarding marriage and more potential for financial independence. Equally important, the Morrill Land-Grant Act created a legal precedent for women to be treated equally by the federal government of the United States (Gallagher, 2021).

As much as women’s rights in the West improved over time, there was still little progress in the struggle for women’s suffrage. This was equally true in the East and the South. By the end of the 19th century, it appeared as if the women’s suffrage movement had stalled.

The 19th Amendment

At the turn of the 20th century, women still could not vote in the United States. As the founders of the women’s rights movement aged and passed away, it felt like the suffrage movement had stalled. In time, new radical women activists stepped up to carry on the cause. Women like Mary Church Terrell and Carrie Chapman Catt infused new life and ideas into the women’s suffrage movement (Cobbs, 2023).

Mary Church Terrell was a wealthy, upper-class, educated Black woman. As a young woman, she traveled in Europe and “tasted the joy of not thinking about color” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 140). In 1892, Terrell, with like-minded women, started the Colored Women’s League (CWL). As an organization, the CWL focused on various issues faced by the Black community, including education, Jim Crow laws, and women’s rights. In 1896, the CWL and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin’s Woman’s Era Club joined forces to create one organization, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). By 1924, the NACW had approximately 100,000 members (Cobbs, 2023). Terrell was praised for building bridges between people with shared interests. Terrell “believed that enduring progress could be achieved only through interracial cooperation” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 152). She was not alone. Susan B. Anthony continued to push for Black women to become members of the primarily White women’s rights movement and asked Terrell to join the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Terrell agreed and, by 1901, began travelling across the United States to speak to integrated audiences. Terrell educated her audiences about “the progress of her gender and race, and violations of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 155). In 1904, Terrell was invited to speak at the International Council of Women’s Conference in Berlin and became an international sensation.

Video: Mary Church Terrell’s Advocacy & Impact on Voting Rights

Speech Transcript: The Strongest for the Weakest – 1904 by Mary Church Terrell

Discussion Questions

- What were Mary Church Terrell’s critical contributions to the women’s suffrage movement? How did she navigate the intersection of race and gender in her advocacy efforts?

- How did Mary Church Terrell’s activism challenge or complement the work of other prominent suffragists and women’s rights advocates of her time? In what ways did she agree with or differ from other leaders?

- How did Mary Church Terrell’s activism contribute to the broader women’s rights movement and the fight for racial equality? What lasting impact did her work have on these movements?

As Jim Crow laws continued to oppress Black people in the United States, tension increased between Black and White women in the suffrage movement. Some White women championed White supremacy by actively endorsing suffrage for White women only (Cobbs, 2023). “Rebecca Felton, a former slaveholder and the wife of a liberal Congressman from Georgia, advocated for both women’s suffrage and the lynching of every ‘Black fiend who lays unholy and lustful hands on a white woman’” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 157). Many Southern suffragists organized against women like Felton, but had little success in impacting the racist rhetoric.

Many White Women in the suffrage movement felt they needed to make difficult decisions to obtain the right to vote. They understood that if women won the suffrage battle in the United States, most Black women would not be allowed to exercise their right to vote, as the majority of Black Americans still lived in Southern states with oppressive Jim Crow laws (Cobbs, 2023). If the women’s suffrage movement were successful and obtained the right to vote for all women, that “would inscribe a non-racist, non-sexist law in the Constitution that nominally doubled the number of Black voters” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 170). Most women’s suffrage organizations took the middle path and continued to fight for all women but did not confront concerns about Jim Crow laws.

Video: Untold Stories of Black Women in the Suffrage Movement

Discussion Questions:

- What was your initial reaction to the quote, “I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams?” How does this quote resonate with you, and what emotions or thoughts does it evoke? How is the quote significant in a discussion of Black women’s suffrage?

- How did Black women navigate the racial dynamics and exclusions within the mainstream suffrage movement? What strategies did they employ to assert their rights and advocate for racial and gender equality?

- How can we ensure that the contributions and stories of Black women in the suffrage movement are more fully recognized and integrated into historical narratives? What steps can be taken to address the historical erasure of their contributions?

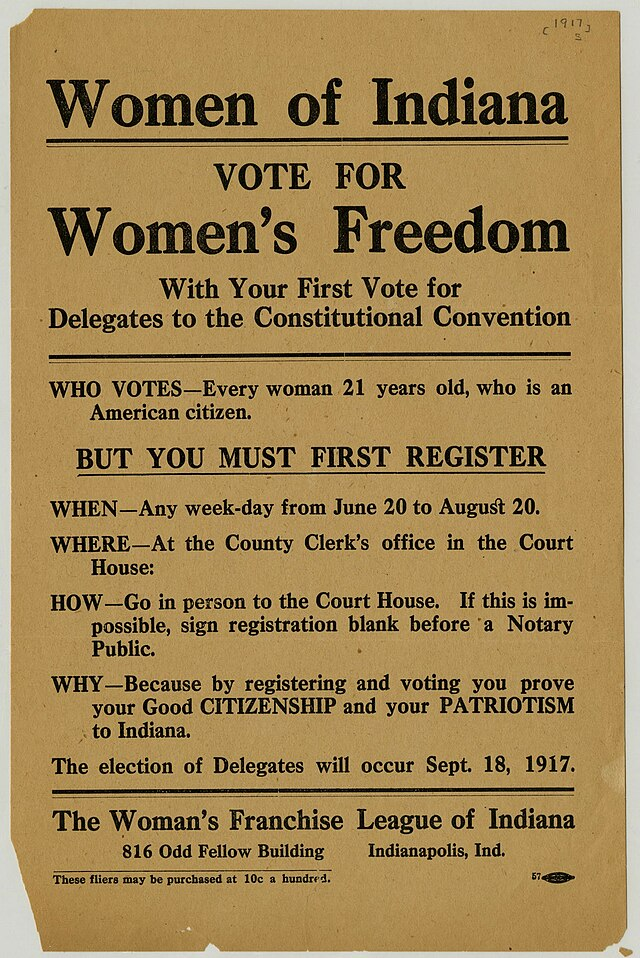

In 1914, for the first time since 1887, the United States Congress agreed to allow a women’s suffrage bill, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, to be brought to the floor for a vote. In support of the Amendment, Terrell and other Black women of the NACW marched with White suffragists. A Black newspaper reported on the march, writing “No color line existed in any part of it. Afro-American women proudly marched right by the side of the white sisters” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 172).

Suffragists knew that the Susan B. Anthony Amendment would not pass. However, they needed to gain information on how Congress would vote and what barriers must be overcome for future success. After Congress engaged in a three-hour debate, it was clear that racism was the biggest obstacle to women obtaining the right to vote. Extremists like Senator James Vardaman went as far as to propose “trading Black male suffrage for women’s suffrage” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 173).

As the United States entered World War I, American women were needed to fill jobs left by soldiers going overseas. Women, such as Carrie Chapman Catt, took advantage of this need. When asked by President Wilson to assist with promoting the war effort (Faderman, 2022; Griffith, 2022), Catt agreed to support Wilson’s war efforts in exchange for his support of women’s suffrage (Cobbs, 2023). In 1918, Wilson honored his agreement with Catt and supported the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It is unclear if Wilson believed in women’s rights or if he was concerned about the image of the United States. By 1918, 24 countries, including Germany, had already granted women the right to vote, and the United States was lagging behind the rest of the world (Catt & Shuler, 2020; Cobbs, 2023).

Even with President Wilson’s support, there was no guarantee that Congress would pass the Susan B. Anthony Amendment or that the required number of states would ratify it. Suffragists, including Terrell and Paul, continued to fight hard. Anti-suffragists increased their rhetoric, claiming suffragists were anything from abnormal to socialists. “The omnipresent threat of Southern backlash constrained interracial cooperation among suffragists, regardless of their personal views or relationships” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 179). The United States Senate voted against women’s suffrage four times: in 1887, 1914, 1918, and February, 1919. However, on June 4, 1919, the Senate passed the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. Ironically, the segregationist senators helped the Amendment pass by two votes (Cobbs, 2023).

On August 18, 1920, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, known as the 19th Amendment, was ratified. It simply read, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” (Griffith, 2022, p. 19). The addition of one sentence to the Constitution took decades to achieve.

Not all states ratified the 19th Amendment. Mississippi, the last state to ratify, did not do so until 1984 (Griffith, 2022). Although the ratification of the 19th Amendment was finally successful, it had been a long and, in many ways, heartbreaking fight. Of the victory, Catt wrote,

To get the word male in effect out of the constitution cost the women of the country fifty-two years of pause-less campaign thereafter. During that time they were forced to conduct fifty-six campaigns of referenda of male voters; 480 campaigns to get Legislatures to submit suffrage amendments to voters; 47 campaigns to get State constitutional conventions to write woman suffrage into State constitutions; 277 campaigns to get State party conventions to include women suffrage planks; 30 campaigns to get presidential party conventions to adopt woman suffrage planks in party platforms, and 19 campaigns with 19 successive Congresses …Young suffragists who helped forge the last links of that chain were not born when it began. Old suffragists who forged the first links were dead when it ended. (Cobbs, 2023, p. 181)

Limitations of the 19th Amendment

The ratification of the 19th Amendment was a milestone. However, it also had significant limitations. In the United States, racism still trumped the law. Although the 19th Amendment included Black women as United States citizens, it did not protect their right to vote. States had immense power over voting rules, and many did whatever they could to stop Black people, including women, from voting. Black women were subjected “to blatantly discriminatory practices, including unfairly administered literacy tests and ‘grandfather’ clauses that prevented descendants of enslaved people from voting while allowing illiterate whites to vote if their grandparents had” (Griffith, 2022, p. 23). Other tactics employed by states included White-only primaries and accusations of missed registration deadlines.

In addition to Black Americans being discriminated against in their right to vote, the 19th Amendment also failed to protect Indigenous women, women who lived in United States territories, or the District of Columbia (Griffith, 2022). Mary Church Terrell, who had fought tirelessly for women’s suffrage, lived in the District of Columbia and “never did cast a ballot” (Griffith, 2022, p. 182). She died ten years before the District of Columbia passed suffrage in 1964 (Cobbs, 2023).

The 19th Amendment did not apply to Indigenous women because they were not citizens of the United States. However, not all Indigenous people desired United States citizenship. Some Indigenous leaders were concerned that if they obtained citizenship, the United States government would use that as a justification to negate the treaty and property rights guaranteed to Indigenous people (Blackhawk, 2023). Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, from the Turtle Mountain Chippewa community, and Zitkala-Sa, from the Yankton Sioux community, were both active in the women’s suffrage movement and the movement for Indigenous rights (Griffith, 2022). Although Zitkala-Sa advocated for Indigenous citizenship, she did not believe it would resolve the systemic racism that Indigenous people faced in the United States. Ultimately, Zitkala-Sa believed citizenship was “a necessary remedy for a broader illness” (Blackhawk, 2023, p. 385).

Video: When Voting Rights Didn’t Protect All Women

Discussion Questions

- How did voting rights not protect all women?

- Do you see voting rights as a victory for suffragettes or a setback for the broader fight for racial equality? Explain your answer.

- How does the historical context of voting rights and racial inequality impact the current discourse on voting rights and representation for marginalized groups? What connections can be drawn between past and present struggles for voting rights?

Post-19th Amendment

After the ratification of the 19th Amendment, many suffragists split into special interest groups. Some women, such as Jane Addams and Ellen Starr, focused their energy and skills on working with immigrants to the United States. Addams and Starr established Hull House, the first settlement house in the United States to serve immigrants and working-class people (Griffith, 2022). Because of her work, Addams was the second woman to win the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1931 (Nobelprize.org, n.d.).

Some women, such as Mary Burnett Talbert, focused on the brutality of White supremacy. Talbert became the chair of the NAACP Anti-Lynching Committee and fought tirelessly to end the “legal terrorism of lynching, dismemberment, and burning in the Jim Crow South, where 90% of African Americans lived in 1920” (Griffith, 2022, pp. 34-35).

Some women, such as Alice Paul, remained focused on women’s rights. On September 10, 1920, while giving a speech to the leaders of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), Paul stated,

It is incredible to me that any woman should consider the fight for full equality won. It is just the beginning. There is hardly a field, economic or political, in which the natural and accustomed policy is not to ignore women…. Unless women are prepared to fight politically, they must be content to be ignored politically. (Griffith, 2022, p. 40)

Paul’s slogan, Equality Not Protection, expressed her belief that women deserved “political sameness” (Griffith, 2022, p. 43). Paul believed that gender-based protections, such as those in the labor reform movement, prohibited women’s advancement toward equality.

The Equal Rights Amendment

Alice Paul introduced the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) at the National Women’s Party (NWP) convention in 1921 (Griffith, 2022). The ERA, as written by Paul, declared: “No political, civil, or legal disabilities or inequalities on account of sex or on account of marriage, unless applying equally to both sexes, shall exist within the United States or any territory subject to its jurisdiction thereof” (Griffith, 2022, p. 43). Not everyone was a proponent of the ERA. Some women in the labor reform movement, such as Florence Kelly, believed the ERA would undo their accomplishments. Kelly called the ERA “miserable, monstrously stupid and deadly” (Griffith, 2022, p. 43).

The ERA, sponsored by the NWP, reached the floor of the United States Senate in 1946, where it was defeated (Faderman, 2022). The ERA had surprising opponents, such as women in the labor reform movement like Kelly and Eleanor Roosevelt, a Women’s Trade Union League member. The NWP tried to revise the ERA in the early 1960s with little success. Although many women worked outside of the home, the social convention still saw women as primarily homemakers. Congressmember John F. Kennedy stated that a “woman’s primary responsibility is in the home” (Faderman, 2022, p. 311).

Others, such as Congressmember Howard W. Smith, supported the ERA not because he supported women’s rights but because “he was opposed to protective legislation for them” (Faderman, 2022, p. 311). Although Paul and Smith were not philosophically aligned in many ways, they worked together with some success. In 1963, the Civil Rights Act was presented to the House Rules Committee. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act “banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, and national origin” (Faderman, 2022, p. 311). Paul asked Smith to add sex to Title VII, and Smith agreed. With Smith’s endorsement, sex was successfully added to Title VII and signed into law on July 2, 1964 (Faderman, 2022).

In 1970, the ERA was again presented to Congress. Although there was continued opposition within Congress, the ERA was passed by the House of Representatives in 1971 and the Senate in 1972. However, for the ERA to be enacted into law, it needed to be ratified by 38 states. Members of Congress who opposed the ERA had set “an arbitrary time limit of seven years for ratification” (Faderman, 2022, p. 353). By 1973, 30 states had ratified the ERA.

During this time, the ERA gained a new opponent. Phyllis Schlafly and her STOP (Stop Taking Our Privileges) campaign rallied heavily against the ERA. Schlafly viewed the ERA as “a bottomless pit of horrors” (Cobbs, 2023, p. 295). She feared the ERA would make women subject to the military draft, damage labor protections for women, force happy homemakers to work, and negate women’s rights to alimony and child support (Cobbs, 2023). Schlafly used her fears to motivate “an army of radical-right women followers” (Faderman, 2022, p. 355).

By 1977, the ERA was stalled, with only 35 of the necessary 38 states having ratified it. Congress granted a three-year extension of the ERA’s ratification time limit. However, Schlafly’s campaign was highly successful. Not only did her campaign stop some states from ratifying the ERA, but other states, such as Tennessee, withdrew their ratification (Faderman, 2022). By 1982, the ERA’s time limit extension had expired, and the ERA was never ratified (Cobbs, 2023).

Women’s Rights Movement: Second Wave (1960s to Current)

Just as the anti-slavery movement had inspired the first women’s rights movement, the second wave of the women’s rights movement was inspired by the civil rights movement. Many women in the second wave were also involved in the civil rights movement, where they learned how to advocate, march, and protest (Faderman, 2022).

In 1963, Betty Friedan wrote in The Feminine Mystique that women were unhappy due to “the problem that has no name” (Friedan, 2001, p. 10). Friedan theorized that because women had repressed their needs to do more than be a “happy housewife,” they felt unhappy and worthless. Friedan’s ideas resonated with many American women, and by 1966, she had sold over three million copies of The Feminine Mystique.

In 1966, at the third annual conference for the President’s Commission on the Status of Women, Friedan, Aileen Hernandez, Inez Casiano, Shirley Chisholm, and Pauli Murray established the National Organization for Women (NOW; Berry & Gross, 2020; Faderman, 2022). NOW fought for the ERA. After its defeat, similar to the post-19th Amendment ratification, many women involved in NOW splintered to focus on other special interests. Some women like Marie Bass, Betsy Crone, and Ellen Malcom focused on the need for more women in political positions of power.

Ellen Malcolm initially founded EMILY’s (Early Money Is Like Yeast) List. EMILY’s List is registered as a political action committee and operates as a donor network for women political candidates (Griffith, 2022).

Video: Ellen Malcolm, Founder of EMILY’s list

Discussion Questions:

- What impact has EMILY’s List had on increasing the representation of women in politics?

- What role does money play in successful political campaigns? Why is this relevant to women’s rights in the United States?

- In what ways has politics changed since Ellen Malcolm formed EMILY’s List? How have these changes impacted the organization and its effectiveness?

- How can the principles and strategies of EMILY’s List be applied to support other underrepresented groups in politics? What parallels can be drawn between supporting women and helping other marginalized communities?

By its second national convention, and partially due to Friedan’s popularity and force of personality, NOW had become an organization of mostly middle-class White women. Before the term “intersectionality” was coined by Kimberlee Crenshaw in 1989, Black women lived the double jeopardy of being Black and being a woman (Berry & Gross, 2020; Griffith, 2022). While Black women benefited from some of NOW’s initiatives, such as the protest against the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC), they had additional challenges that middle-class White women did not share. Many Black women did not relate to Friedan’s “problem with no name,” as they had always had to work due to economic inequalities and systemic racism (Faderman, 2022; Griffith, 2022). “Black women were already … roughly equal to Black men—just as they had been in the days of slavery, when their gender had not saved them from abuse” (Faderman, 2022, p. 321).

In 1973, Florence Kennedy, Margaret Sloan, and Eleanor Holmes established the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) in reaction to NOW, middle-class White feminists, and Black men. The NBFO’s Statement of Purpose read,

The women’s liberation movement has been characterized as the exclusive property of so-called white middle-class women, and any Black women involved in this movement have been seen [by Black activists] as selling out, dividing the race, and an assortment of nonsensical epithets (such as lesbian, dyke, and bull dagger). (Faderman, 2022, p. 339)

While NBFO reflected some Black voices, Black lesbians, such as Audre Lorde and Gloria Hull, felt disconnected from NOW and NBFO. They worked together and formed the Combahee River Collective, intending to support women of all identities. They wanted to look beyond gender and race for inclusion. The women of the Collective were the first to define identity politics and interlocking systems of oppression.

Video: Black Feminist Organizations

Discussion Questions

- In what ways have Black feminist organizations contributed to the broader women’s rights movement?

- How have Black feminist organizations navigated and challenged systemic racism and sexism within the broader feminist movement?

- What lessons can current social justice advocates take from the history and ongoing work of Black feminist organizations?

Reproductive Justice Movement

Reproductive justice is “the complete physical, mental, spiritual, political, social, and economic well-being of women and girls, based on the full achievement and protection of women’s human rights” (Ross, 2006). The quest for women’s reproductive justice has existed since European colonists first invaded America. Although reproductive injustice has affected and continues to affect all women, women of color have been disproportionately affected.

The history of Black women in the United States is fraught with reproductive injustice. During the many atrocities of the American slave trade, enslaved women’s bodies were not ever their own, and “their gender was unacknowledged most of the time” (Faderman, 2022, p. 50). However, at the same time, slave owners were invested in enslaved women’s reproductive functions as a financial investment. Enslaved women’s economic value increased with each completed pregnancy, and slave owners often forced mating between slaves. However, pregnancy was not considered a reason to excuse enslaved women from work or punishment.

If a pregnant woman did something to anger the overseer, he might dig a hole in the ground big enough to contain her stomach, force her to lie down, and then beat her—in that way protecting the unborn child, which was the master’s property. (Faderman, 2022, p. 50)

Before the 1870s, midwives and other female healers assisted women through birth, contraception, and even abortion. By the 1870s, however, the practice of medicine was established as a male profession, and medical doctors lobbied for regulated qualifications, which disqualified midwives from practicing medicine (Griffith, 2022). In addition, at the time, women were not accepted into medical schools in the United States. Thus, for the first time in history, reproductive concerns in the United States were no longer in the control of women but, instead, in the control of men.

Childbirth

In the early 1900s, many medical professionals refused to use anesthesia during childbirth despite it having been available since 1831. “Aside from beliefs that anesthetics were dangerous, time-wasting, and likely to drive women erotically insane, most physicians still felt that they should be the judges of the pain of childbirth” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 141). As part of the quest for reproductive justice, women challenged the idea that pain was a necessary and inevitable part of childbirth. “But the intention to have women reclaim their bodies from medical control was trampled in the obstetricians’ race to transform childbirth into an illness that required drugs, instruments, and brutal procedures” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 153).

Birth Control

In 1915, Mary Ware Dennett, inspired by the advocacy of Margaret Sanger, established the National Birth Control League. The National Birth Control League was “the first American organization to campaign to legalize contraception and release women from the wretchedness of unwilling parenthood” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 153). Sanger, a strong advocate for access to birth control, published a newsletter, The Woman Rebel, where she “connected reproductive choice with women’s economic emancipation” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 154). Sanger, in her quest to provide birth control education, was a true advocate of women’s choices.

In 1917, Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States in Brooklyn, New York. Sanger believed that giving women access to birth control would reduce the need for abortions and would increase sexual pleasure (Cleghorn, 2021). Unfortunately, Sanger did not have the law on her side, and the clinic was raided and shut down. In addition, Sanger was arrested multiple times for being a public nuisance and for the distribution of lewd materials, which were materials about contraception. However, Sanger did not give up. In 1923, Sanger opened the first legal birth control clinic in the United States (Faderman, 2022)

Due to the advocacy of Sanger and others, contraceptive methods and education became available to women in the United States. Unfortunately, many of those contraceptive methods, including diaphragms, sponges, and condoms were unreliable, required advance planning, or required the cooperation of men. However, as eloquently stated by Cleghorn (2021), “[it] is an anger-inducing reality that the beginnings of reproductive justice were entangled with ideologies about how women-especially Black women, other ethnically diverse women, and vulnerable women-should be controlled and regulated” (p. 165).

By 1921, Sanger founded the American Birth Control League, eventually known as Planned Parenthood, and continued to support women’s access to birth control and education about their bodies. By the late 1930s, approximately 400 birth control clinics existed in the United States (Cleghorn, 2021). In 1941, the National Council of Negro Women was the first national women’s organization that officially endorsed contraceptives for women.

In the early 1950s, Sanger, both personally and through Planned Parenthood, provided partial funding to research an oral contraceptive for women. Sanger’s friend, Katharine Dexter McCormick, provided the rest of the financing (Planned Parenthood, n.d.). By the mid-1950s, clinical trials began for an oral contraceptive (Cleghorn, 2021).

The first clinical trials for an oral contraceptive were held in Puerto Rico. The trial utilized racially biased, unethical, and unsafe methods. “The women of Puerto Rico were regarded as submissive enough to be coerced into continuously taking an uncharted drug” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 272). Although Puerto Rican women, due to poverty, had a genuine need for birth control methods, they were not informed that they were being used as test subjects, nor were they informed of the potential side effects of the drug (Cleghorn, 2021).

On June 23, 1960, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the release of Enovid, commonly referred to as the Pill. Enovid was the first oral hormonal birth control for women (Cleghorn, 2021; Griffith, 2022). “Historical fears that women’s sexual freedom would lead to the destruction of moral and societal values pervaded medical, religious, and governmental attitudes towards the pill from its very inception” (Cleghorn, 2021, p. 270). By its release date, it was illegal for doctors to prescribe Enovid in 30 states (Griffith, 2022).

In 1965, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that married women had a constitutional right to privacy, which included the decision to use birth control. Because Griswold only applied to married women, there were still many women who could not use Enovid, including women under the age of 21 without parental consent (Cleghorn, 2021). It was not until 1972 when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Baird v. Eisenstadt that unmarried women, due to their constitutional right to privacy, could legally use birth control (Griffith, 2022).

Video: Planned Parenthood: History of the Pill: Why Birth Control Matters

Discussion Questions

- What role did birth control play in women’s rights historically?

- What role does birth control play in women’s rights today?

Eugenics and Forced Sterilization

While Sanger was fighting to give women access to birth control, eugenics gained popularity in the United States. Eugenics was a pseudoscience that postulated that deficits are genetic. Thus, it was believed that people with disabilities, people of certain races, and poor people should not be allowed to have children. Between 1907 and 1979, over 64,000 American women were forcibly sterilized based on their race, class, and intellectual disability.

In 1924, the State of Virginia passed a law that mandated the forced sterilization of women deemed intellectually disabled. That same year, Dr. Albert Priddy, who had performed hundreds of forced sterilizations, petitioned to sterilize Carrie Buck, an 18-year-old White woman who was institutionalized in the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded. According to Griffith (2022), Buck was raped by one of her relatives and had an illegitimate child. She was accused of being promiscuous and feebleminded. To guarantee that the Virginia law was legally sound, the Virginia Colony hired an attorney for Buck. In 1927, Buck v. Bell went to the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court upheld that the State of Virginia had the right to sterilize Buck. In his majority rule, Justice Holmes wrote, “being swamped with incompetence…Three generations of imbeciles is enough.” (Griffith, 2022, p. 56). The Supreme Court decision allowed the State of Virginia to sterilize Carrie Buck, and she underwent the procedure on October 19, 1927.

In the 1960s, during the civil rights fight, North Carolina (1961) and Mississippi (1964) passed forced sterilization laws. The forced sterilization of Black women occurred so often in southern states that the procedure was known as the “Mississippi appendectomy” (Griffith, 2022, p. 56). The Mississippi law, aptly dubbed the Genocide Bill, was initially written so that any woman who had a second illegitimate child would be charged with a felony punishable by either prison or sterilization. When the Mississippi law was passed, it changed the charge from a felony to a misdemeanor and reduced the sentence to 90 days in jail or sterilization (Griffith, 2022).

Unfortunately, in the United States, forced sterilization of women is not just history. According to a 2022 report from the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC), 31 states and the District of Columbia currently have laws on the books that allow forced sterilization of disabled women. Only two states specifically ban forced sterilization, and the other 17 states have either statutes with loopholes or have had court rulings that have suggested forced sterilization may be possible (NWLC, 2022).

Abortion

Despite having access to birth control methods, millions of American women will experience an unplanned pregnancy in their lifetime. It is important to note that not all women in the United States will want or have an abortion. However, abortion has always existed in the United States regardless of legality. The most common reasons American women have abortions are “rape, incest, poverty, desperation, fatal fetal abnormalities, and risk to the mother” (Griffith, 2022, p. 363). Therefore, the most controversial issue in the women’s reproductive justice movement is abortion.

Before the early 1800s, common law allowed free women to have abortions up until fetal movement, known as quickening, was detected. Thus, it was the pregnant woman who decided when and if they chose to abort, as only they could feel fetal movement (Griffith, 2022). Abortions were induced using herbs and some medications, usually given by midwives (Cleghorn, 2021). “For the most part, the persons who performed all manner of reproductive health care were women—female midwives. Midwifery was interracial; half of the women who provided reproductive health care were Black women. Other midwives were Indigenous and white” (Goodwin, 2020, para 5).

White male gynecologists viewed skilled Black and Indigenous midwives as an affront to their professional image (Goodwin, 2020) and, by the early 1800s, states had passed laws that limited or prohibited abortion. In 1821, the State of Connecticut passed the first law that limited access to abortion. Connecticut’s law banned the use of herbs, a common way to induce abortion, and made their use punishable by a life sentence in prison. In 1845, the State of Massachusetts was the first to pass a law that prohibited abortion for any reason (Griffith, 2022). By 1857, the American Association of Medicine (AMA) “coordinated a national drive to outlaw abortion and midwifery, both to ensure women’s safety and to eliminate competition for obstetrical patients” (Griffith, 2022, p. 193). The AMA succeeded in both goals.

Between 1821 and 1880, 40 states and territories had established anti-abortion laws and, by 1900, all 45 states had laws that made abortion illegal. Any exceptions to the law were decided by doctors (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012; Griffith, 2022). “Doctors used their judgment in cases of rape or risk to the mental or physical health of the mother. If two psychiatrists and one physician agreed, a woman could have a therapeutic abortion” (Griffith, 2022, p. 194). Additionally, in many areas in the United States, hospitals and medical clinics were segregated by race, which meant that access to abortion was even more limited for women of color (Cleghorn, 2021; Griffith, 2022).

During the 1950s and 1960s, the number of illegal abortions performed was estimated from 200,000 to 1.2 million each year (Gold, 2003). As discussed above, birth control was not legal for single women until 1972. Therefore, women needed access to safe abortions. Many doctors provided abortions for women who had the necessary medical connections and the money to pay for the procedure. For women who had neither, often marginalized women, abortion was either not available or was unsafe (Garrow, 1999).

Video: Abortion Was Illegal. This Secret Group Defied the Law

In 1965, Heather Tobis Booth helped a friend find a doctor willing to perform an abortion. Booth, as a result of that experience, started the Jane Collective, a network of women that offered information about safe abortion providers, safe houses, and counseling. Because of their experiences with unlicensed abortion providers, some of the women of the Jane Collective learned how to perform abortions. Between 1969 and 1972, women in the Jane Collective performed 12,000 illegal abortions (Griffith, 2022).

Discussion Questions

- The Jane Collective is seen as an advocacy group. Do you agree that this work was advocacy?

- Where does the right to choose fit into the women’s rights movement?

By the 1970s, “there was a distinct trend in the states…toward liberalization of abortion statutes” (Ginsburg, 1985, pp. 379-380). Some states, such as Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington, permitted first-trimester abortions with no restrictions. However, some states, such as Georgia and Texas, had highly restrictive abortion laws (Ginsburg, 1985). By 1970, approximately 20 constitutional cases were challenging restrictive abortion laws (Garrow, 1999).

In 1971, two abortion law cases, Doe v. Bolton and Roe v. Wade, were brought to the United States Supreme Court. Doe v. Bolton challenged a Georgia state law that only allowed abortions in cases of rape, fetal deformity, or potential of severe harm to a woman. The Georgia law also required abortions to be performed in hospitals after a woman was examined by three medical doctors and a committee approved the procedure. Roe v. Wade challenged an 1857 Texas state law that banned abortion unless determined to be lifesaving for a woman and punished participants of illegal abortion with up to five years in prison (Griffith, 2022).

In 1973, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Doe v. Bolton and Roe v. Wade. In Doe v. Bolton, the United States Supreme Court ruled in favor of Doe. The Court concluded that abortion rights should not be without specific parameters, but that the requirements in the State of Georgia were unduly burdensome. Doe v. Bolton, although a critical case, had limited impact because of its focus on the specific way the State of Georgia restricted abortion access (Griffith, 2022).

Roe v. Wade was a critical case because it challenged the right of states to ban abortion altogether, and the Court’s ruling in Roe signified that women had control over decisions about their bodies. Specifically, the outcome of Roe v. Wade upheld the ideal of liberty derived from the 14th Amendment (Griffith, 2022). Although Roe v. Wade was challenged multiple times, the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed its decision in cases such as Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey; that women had the essential liberty of bodily autonomy, and that individual states could not ban abortion before viability of a fetus (Faderman, 2022; Griffith, 2022). This changed in 2022 with the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision (Griffith, 2022).

Roe v. Wade Backlash

In Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court concluded that “access to abortion was a fundamental right” (Griffith, 2022, p. 196). However, the Court’s ruling included a loophole for states’ compelling interest, which “could justify restrictive state regulations” (Griffith, 2022, p. 196). An example of a compelling state interest was that in the second trimester of a pregnancy, “the state could regulate abortion in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health,” as well as in the third trimester, “given its interest in the potentiality of human life, the state could justify regulating or banning abortion, except for the preservation of life or health of the mother” (Griffith, 2022, p. 196).

In creating these loopholes, the Court’s ruling “created new gestational dividers, three-month increments, and a three-tiered legal framework” as well as making “viability, when a fetus could survive outside the womb, key to abortion law (Griffith, 2022, p. 196). According to Ginsburg (1985), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor described the Court’s use of “the trimester approach as on a collision course with itself” (p. 381). Ginsburg believed that the Court “ventured too far in the change it ordered” because it generated a backlash from conservatives and “stimulated the mobilization of a right-to-life movement” (p. 381). Both O’Connor and Ginsburg would be proved right.

The backlash began as soon as the United States Supreme Court released its ruling on Roe v. Wade. “During the 1970s, a new set of right-wing organizations came into existence” (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012, p. 348) determined to overturn Roe v. Wade. For anti-abortion activists, a major victory was needed. On September 30, 1976, in an attempt by Congress to limit abortions, the Hyde Amendment was passed as an attachment to the Departments of Labor and Health, Education, and Welfare Appropriation Act of 1977 (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012).

The Hyde Amendment restricted Medicaid funding for abortion except in cases of incest, rape, or if a woman’s life was in jeopardy (Adashi & Occhiogrosso Abelman, 2017). After Roe v. Wade but before the Hyde Amendment, Medicaid funded approximately 25% of abortions in the United States. The Hyde Amendment drastically reduced Medicaid funding. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 1977, before the Hyde Amendment was in full effect, 295,000 women had abortions covered by Medicaid. By 1979, only 2,400 women had abortions covered by Medicaid (Engstrom, 2016). “Though the constitutional right to abortion remained intact, anti-abortion forces had succeeded in sharply restricting the access that poor women had to it” (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012, p. 348).

Because the Hyde Amendment is annually reviewed, Congress expanded it to restrict federal funding of abortions for women in the military and the Peace Corps, women with disabilities, women receiving care from Indian Health Services, and federal prisoners (Adashi & Occhiogrosso Abelman, 2017; Engstrom, 2016). In 2010, the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) facilitated the Hyde Amendment’s extension “to federally subsidized private health insurance plans” (Adashi & Occhiogrosso Abelman, 2017, p. 1523). Between 2011 and 2020, historically conservative states passed over 480 restrictions on reproductive rights for women (Griffith, 2022).

On June 24, 2022, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade with their ruling on the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. In 2018, the State of Mississippi passed the Gestational Age Act, which banned abortion after 15 weeks, except if a woman’s life was in danger or if there was fetal abnormality (Byron et al., 2022; Manninen, 2023). The Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case challenged the act as unconstitutional based on prior abortion cases, including Roe v Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

The Court’s ruling on Dobbs erased federal protections for women and gave decisions about abortion back to individual states. The Court ruled that the right to privacy “is controversial because such a right is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution” (Manninen, 2023, p. 358). In its decision, the Court has set legal precedence to overturn other cases won based on the constitutional right to privacy argument. Included in those cases are Lawrence v. Texas, which deemed anti-sodomy laws unconstitutional, and Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same gender marriage in the United States (Manninen, 2023).

The Court’s decision on Dobbs immediately affected the women’s reproductive justice movement. By late 2022, 27 states had enacted laws to restrict or prohibit abortion. For example, the State of Oklahoma made abortion illegal from conception, the State of Ohio made abortion illegal six weeks post-gestation even in cases of incest or rape, and the State of Georgia has extended personhood rights to six-week-old fetuses (Byron et al., 2022). In 2024, Alabama passed a law granting personhood to embryos generated from in vitro fertilization (IVF) (Yousef, 2024).

Many American women believed that bodily autonomy was their guaranteed right in the United States after the Roe v. Wade decision. However, with the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, American women have learned that bodily autonomy was never their guaranteed right in the United States; it was only a law.

Video: Inequality and Abortion Access in the United States

Discussion Questions

- What does unequal abortion access say about the women’s rights movement?

- Where does access to abortion fit into a conversation about women’s rights?

Anti-Rape Movement

The CDC (2014) defines sexual violence as “a sexual act that is committed or attempted by another person without freely given consent of the victim or against someone who is unable to consent or refuse” (p. 11). Although the dominant perception of sexual violence is men as perpetrators and women as victims, men are also victims of sexual violence. That said, in this section, the focus is on sexual violence perpetrated against women.

Indigenous Women

Historically, rape within Indigenous communities was forbidden and rare. Selling sex was non-existent as Indigenous people did not believe one could own another’s sexuality, and that it could therefore not be purchased (D’Emilio & Freedman, 2012). European explorers and colonists sexually assaulted and raped Indigenous women and brought sexual oppression and terrorism to America. According to Griffith (2022), “ [sexual] intimidation and violence against women were patriarchal prerogatives. That power was rooted in religious orthodoxy, white supremacy, territorial conquest, manifest destiny, frontier mythology, and masculine identity” (p. 365).

Black Women

Since the beginning of European colonization of the Americas, White men have used sexual violence to dehumanize and control enslaved Black women. According to Wilson (2021), enslaved Black women were forced to endure,

public nudity; nude physical auction examinations to determine reproductive ability; rape for sexual pleasure and for economic purposes (reproducing children who could become slaves); intentional abortion to women who were pregnant as a result of rape generational poverty; and hypersexualization. (pp. 122-123)

However, sexual violence towards Black women did not end with slavery. “The rape of black women by white men continued, often unpunished, throughout the Jim Crow era. As reconstruction collapsed and Jim Crow arose, white men abducted and assaulted black women with alarming regularity” (McGuire, 2010, p. xviii). Black women testified about the systematic sexual violence they experienced from White men. “They launched the first public attacks on sexual violence as a systemic abuse of women in response to slavery and the wave of lynchings in the post-Emancipation South” (McGuire, 2010, p.xix).

1950s and 1960s