12 Ability in the United States

Bernadet DeJonge and Shannon Raybold

- The reader will examine the experience of disability in the United States.

- The reader will explore historical events in the disability rights movement in the United States.

- The reader will connect the disability rights movement to concepts of social justice.

- This chapter will review core concepts of disability, the history of disability in the United States, and the disability rights movement. It will also discuss disability legislation and connect the disability rights movement to current social justice issues.

Definitions in Disability

Defining disability is a complex task. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA.gov, 2020) states:

An individual with a disability is defined by the ADA as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment. (para 2)

While this may be the legal definition of disability under this federal law, there are many different interpretations of what constitutes a disability. Many argue that all people exist on a spectrum and that differences are to be expected and valued. These individuals take issue with the definition of disability as being substantially different and feel the focus on an unsustainable cultural norm of what it is to be human is inappropriate. Other people identify with the label of disability as a significant part of who they are—they see it as a culture in and of itself. This divergence in perspectives has also contributed to the ongoing debate over language, particularly whether to use first-person (“I have a disability”) or identity-first (“I am disabled”) terminology, reflecting deeper questions of autonomy, pride, and the right to self-definition. An excellent example of this is the Deaf community. In between these two extremes lies a range of different definitions of disability, which is well beyond the scope of this introductory text.

Disability has been seen in different ways throughout history. Often, we refer to these as “models of disability.” See below for some common models.

The moral model: The moral model sees disability as stemming from God. Disability is somehow a mark of shame or wrongdoing. While this is often seen as a historical way of looking at disability, the attitude of morality is still very prevalent in the way that disability is perceived today, particularly globally (Olkin, 2022).

The medical model: The medical model sees disability as something to be cured. The goal is to return the person to as close to “normal” as possible. Experts are professionals with specialized training and language is clinical. In this model, the problem is the person, and the goal is to seek a cure. Medical care is the prevalent need (Olkin).

The social model: The social model sees disability as one aspect of a person’s identity. In this way of viewing disability, the environment and society create the barriers, not the person or their disability. Thus, change needs to occur on a societal level versus changing the individual with a disability. Olkin goes on to say that, “Negative stereotypes, discrimination and oppression serve as barriers to environmental change and full inclusion” (para 5) in the social disability model.

Discussion Questions

- How do you think these models have evolved through time?

- How might these models continue to impact people with disabilities today?

- Do some research—what other models are out there?

Understanding the different definitions of disability and becoming familiar with several important terms in disability studies is crucial. These terms are fundamental to the study of disability:

- Acquired Disability: a disability that one acquires. For example, someone who loses a limb in a car accident or becomes quadriplegic from a diving accident.

- Congenital Disability: a disability someone is born with. For example, Down Syndrome or dwarfism.

- Invisible or Nonapparent Disability: a disability that is not clearly visible. For example, a mental illness, neurodiversity, or learning disability.

- Visible Disability: a disability that is clearly visible. For example, someone with Down syndrome or an amputation.

Website: Disability Definition

Discussion Questions

- How would you define disability? Do some research and see the different ways people define disability.

- What is the role of the individual who identifies with a disability in defining disability?

- Can you think of an instance where it might be hard to tell if a disability is acquired or congenital?

- How do you think each kind of disability (acquired, congenital, invisible/non-apparent, visible) might differ in the experience of the individual?

Accessibility and Universal Design

Accessibility refers to the ability of people with varying abilities to access spaces, goods, education, and services with similar effort. Examples of accessibility include ramps, rails, ASL interpreters, and closed captioning. Accessibility is about equity and creates an environment where goods, education, and services are fair and equitable for everyone by eliminating barriers. Accessibility is about being person-centered and recognizing how someone’s needs can be met in a given environment (SeeWriteHear.com, n.d.).

Universal design is a broader concept than accessibility. Universal design examines how environments, products, and services can be accessed, understood, and used by a wide spectrum of people who wish to use them (Center for Excellence in Universal Design, 2023). The term universal design was coined by Ron Mace, who was an architect and had polio as a child, which led him to be a wheelchair user. Mace’s principles of universal design included equitable use, flexible use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for approach and use (Center for Universal Design, n.d.). The founding principle of universal design is that accessibility to all should be a right, not the privilege of the majority. Universal design assumes that a range of human abilities is typical and expected, not the exception. Therefore, products, spaces, and services should be designed to allow the broadest range of abilities to use them independently and with the same effort. This promotes dignity and respect. Universal design is a human-centered approach (Center for Excellence in Universal Design, 2023).

Some stores and businesses include elements of universal design in their business practices. One example is businesses designating times for people with sensory processing differences. Some movie theaters, stores, and events have made “sensory-friendly” experiences for groups that need a quieter and calmer environment by opening early when the store is not crowded and leaving the overhead music off. Some movie theaters host special showings of movies with a lower volume, with the lights up, and allow people to move around and talk as needed during the film.

Discussion Questions

- How might movie theaters provide accessibility to movies?

- How might movie theaters apply universal design to their theaters?

- What is the difference between the two?

Early American History of Disability

During colonial times in the United States, people with disabilities were looked upon as God’s punishment. This belief stemmed from European views on disability, and it was believed that people with disabilities and, by association, their families were morally corrupt (Ericsson, 2022). It was shameful to have a family member with a disability, and many kept their disabled relatives hidden away in their homes (Fox & Marini, 2024).

During this time, people with disabilities were seen as impetuous children who refused to conform to society’s rules. Thus, fear and often abuse were used to change behavior. Treatment for disability was severe and included bleeding, corporal punishment, and confinement by chains (Ericsson, 2022). In addition, people with disabilities in the early United States were often persecuted or hanged as witches when they acted outside of social norms (Fox & Marini, 2024).

Early in American history, people with disabilities were also seen as a burden in the developing colonies. Being able-bodied was embedded in colonial culture, and every person was expected to contribute in a specific way. People with disabilities fell outside that narrow focus (Nielsen, 2012). Thus, people with disabilities were not permitted to immigrate to the colonies, and if they did arrive, they were often sent back to England (Ericsson, 2022; Fox & Marini, 2024; Reed, n.d.). This policy became official law with the Federal Immigration Act of 1882, which outlawed the immigration of people with disabilities to the United States. This law was used well into the 1900s to discriminate against people with disabilities (Fox & Marini, 2024).

As the colonies grew, Elizabethan poor laws, initially established in England, also migrated to the colonies. Anyone needing assistance would go to the Overseer of the Poor to be judged worthy of aid. Often, men with disabilities were deemed unworthy as it was expected that they would be able to work and support themselves (Wagner, n.d.). As the population in the United States swelled, poorhouses were established. People with disabilities intermixed with the poor in poorhouses regardless of their economic status and were subjected to overcrowding, abuse, and other maltreatment (The Disability Union, 2020).

Nielsen (2012) points out that much of the colonial history of disability focuses on intellectual or cognitive disabilities and less on physical disability. She argues this through a social lens, stating that, at the time, having a physical disability was seen as less of a strain on society. Because of the dangers of living in the newly established colonies, physical disability was expected and was not viewed in the same way as psychological, intellectual, or cognitive disabilities were. Nielsen points out that many colonists with physical disabilities had jobs, married, had children, and were considered productive members of society.

Discussion Questions

- What does it mean to see disability through a social lens? How might this impact how we have seen disability throughout history?

- Do we still see people with physical disability differently than those with cognitive disability?

Into the 1800s, many in the upper and middle class saw poorhouses and, later, institutionalization as a method to cure or treat people with disabilities, including children. However, that was far from how they were run. Poorhouses were intentionally uncomfortable and overcrowded in order to encourage people to work by making accessing assistance miserable (Wagner, n.d.).

Video: The History of the Wayne County Poorhouse and Asylum-Eloise

Discussion Questions

- Many of the people who cared for Eloise’s residents were not doctors but local politicians. What does this say about how people with disabilities were perceived?

- What concerns might you have about the idea that we can “cure” people with disabilities? What kind of consequences might there be to this attitude?

- There were often children in these asylums and poorhouses. What kind of impact might institutionalization have had on the children? What might the short- and long-term consequences of this be?

Following the Revolutionary War, many soldiers found themselves impoverished due to both disability and the low value of Continental currency. Before the war, people who acquired a disability were often sent back to England. However, post-revolution, public sentiment had changed, and many felt that veterans should be helped. For the first time in American history, the government stepped in and provided a pension to disabled soldiers, and the Continental Congress Pension Act was enacted on August 26, 1776 (The Disability Union, 2020). Four more acts followed in 1818, 1820, 1832, and 1836. The Act of 1836 also included widows of veterans (National Park Service, 2023).

Gouverneur Morris, an amputee, helped draft the constitution. He wrote the entire preamble, including the famous phrase “We the People.” Gouverneur Morris had a severely burned and deformed right arm and had lost his left leg below the knee in a carriage accident. All historical depictions of Gouverneur Morris hide his leg and arm (de Groot, 2020).

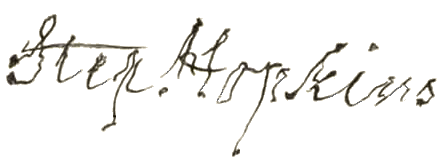

Stephen Hopkins signed the Declaration of Independence and was active in the first Continental Congress. Medical historians believe he had Cerebral Palsy. He was famous for saying, “My hand trembles, but my heart does not.” His signature is larger than all but John Hancock’s (The Disability Union, 2020).

Discussion Questions

- In what ways do the stories of Morris and Hopkins provide a more inclusive and diverse understanding of American history? How can their inclusion in historical narratives impact contemporary views on disability and social justice?

- Considering the erasure or minimization of disabilities in historical depictions, what steps can historians and educators take to ensure a more accurate and inclusive representation of individuals with disabilities?

- When the authors did research on Stephen Hopkins in particular, they found historical websites that did not even mention his disability. What does this say about how we still see disability today?

After the Revolutionary War, public sentiment started to shift from seeing disability as a moral issue to seeing disability as a medical issue. Medical science was growing during this time, and many began to utilize physicians to diagnose and treat disability. In 1825, the U.S. Supreme Court started using the term “disease” instead of “madness” (Nielsen, 2012, p. 68) to define cognitive disabilities. As physician training became standardized, practitioners of folk medicine and midwives who had cared for people in the past were left behind. Physicians now control diagnosis and treatment (Nielsen, 2012).

Institutionalization

Treatments for those with disabilities continued to be varied and often cruel throughout the late 1800s. As treatment shifted from home-based care to physician-care, many experienced bloodletting, confinement, purging, labor, restraint, and immersion therapy in their homes at the hands of physicians. Those who were institutionalized also faced cruelty in their treatment and were often confined, chained, beaten, and starved. Often, institutions lacked heat, blankets, enough food, or appropriate bedding (Nielsen, 2012).

As the medicalization of disability took hold, institutionalization came into fashion to treat people with disabilities. The first hospital-style institution in the United States was the American Asylum for the Deaf, founded in 1817 (Nielsen, 2012). Many institutions were private initially, but by the mid-1800s, publicly funded institutions began to open for individuals with disabilities. Thus began the split between private care and public assistance in care. As happens today, as well, many who could not afford to pay for care ended up in homeless shelters (almshouses) and prisons (Wagner, n.d.).

The rise of institutionalization was a significant shift in the experience of individuals with disabilities in the United States. In the mid-1800s, most children and adults who had disabilities were generally integrated into society. Many went to school, worked, and married. However, as institutionalization took hold, societal views again shifted. Nielsen (2012) points out that “Family members of those with cognitive disabilities, once admired for their devotion and care, now experienced shame. With increased shame came increased institutionalization” (p. 72).

Institutionalization varied by location and more institutions were founded in the northern states than in the southern states. Those in the southern states tended to be of poorer quality unless they were specifically for the wealthy. Institutions were often self-sustaining as the concept of the almshouse or poorhouse shifted towards poor farms. Most institutions were in the country, away from the public eye, and many had working farms. These working farms are often cited as the start of vocational rehabilitation therapy (Ericsson, 2022).

Video: Institutionalized: The Story of State Hospitals

Discussion Questions

- Were you aware of the history of institutionalization in the United States? What surprised you the most about this history?

- In what ways do you think the legacy of institutionalization has contributed to societal perceptions and stigma surrounding disability?

- Why is it important for the general public to be aware of the history of institutionalization of people with disabilities? How can increased awareness contribute to social justice and inclusion?

- What kinds of impacts might the historical experience of institutionalization have on the experience of having a disability today?

Indigenous Populations and Disability

The Indigenous populations of the Americas had a different lens on disability than their European counterparts. In Indigenous tribes, disability was often seen as a normal part of life. Some tribes felt that disability was due to an imbalance or angering of the gods. However, most did not punish the individuals or families for this. They would do what was needed to right the imbalance, and the person would be integrated into society. Just as some people were better at hunting and some at making clothing, people with disabilities would be put to work utilizing their strengths to support the community (Nielsen, 2012).

As diseases brought from Europe decimated Indigenous tribes, being able to care for those with disability became more complex. Smallpox brought disability to the tribes, as those who survived were often blinded and scarred. Tribes no longer had solid and interconnected societies, and people with disabilities who did not perish in waves of epidemics could not be cared for in the same way. In addition, the shifting priorities of tribes to war with the colonists may have impacted the perception of people with disabilities who were not fit to battle their oppressors (Nielsen, 2012).

Did you know that Indigenous people used sign language amongst tribes? This allowed tribes to communicate with each other, even when they did not speak the same language. In addition, it created opportunities for those who were Deaf or hard of hearing to communicate. This is a great historical example of universal design (Nielsen, 2012).

Discussion Questions

- Were you aware that Indigenous tribes used sign language to communicate with each other? How does this change your understanding of the communication methods used by Indigenous peoples historically?

- How might the use of a shared sign language among tribes have impacted cultural exchange and the preservation of different languages and traditions? What are some potential benefits and drawbacks of this practice?

- In what ways did the use of sign language among Indigenous tribes provide opportunities for Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals to participate in their communities? How does this compare to the inclusion of Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in other historical contexts?

- Are there stereotypes about Indigenous people using sign language? What tone do these stereotypes carry?

African Slavery and Disability

Nielsen (2012) states: “Disability permeated the ideology, experience, and practices of slavery in multiple and profound ways” (p. 42). She goes on to state that owning slaves who were perceived to be sound of mind and body was essential to slave traders and owners in the United States. As Black people were kidnapped from their homes in Africa, those who were not fit to work were often killed. Those who were captured endured disease, malnutrition, mental stress, and abuse on their journey to the United States. Frequently, this experience led to disability. Chattel slaves who arrived with disabilities in the United States did not have value and were often killed or left to die on their own when they did not sell for a high price (Nielsen, 2012).

Nielsen (2012) also points out that chattel slavery was justified by comparing Africans to people with disabilities. Enslaved people were said to lack intelligence in direct comparison to individuals with intellectual disabilities. It was believed that enslaved people could not survive without White supervision and care due to their physical and mental defects. Nielsen goes on to state that “The concept of disability justified slavery and racism—and even allowed many whites [sic] to delude themselves, or pretend to delude themselves, that via slavery they beneficially cared for Africans incapable of caring for themselves” (p. 57).

In addition to using the language of disability to justify chattel slavery, the experience of chattel slavery often led to disability. Chattel slavery involved heavy, repetitive labor as well as poor housing, poor working conditions, and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. Enslaved people were often intentionally disabled or disfigured by cropped ears, scars, gunshot wounds, inadequate medical care, improperly healed fractures, and loss of fingers, toes, and limbs. When this occurred, enslaved people with disabilities had less value to their White enslavers. That said, they still labored. Often, disabled chattel slaves worked doing menial work. In addition, chattel slaves with disabilities were frequently utilized to care for both enslaved children and to work caring for White children. When chattel slaves with disabilities were deemed not useful, they were either killed or set “free” to die (Nielsen, 2012, p. 63).

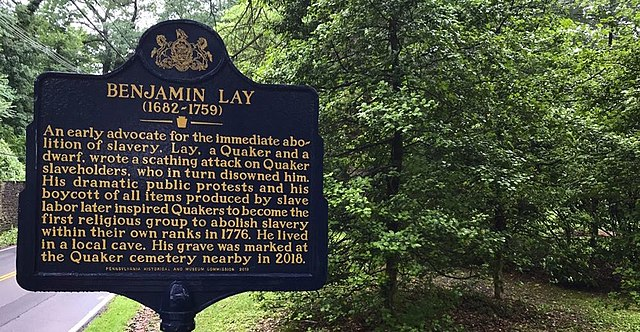

Abolitionists (people who were anti-slavery) also used the language of disability to further their cause. Many argued that slavery had disabled the slaves by forcing them to be dependent on their White masters. To further their cause, they published detailed reports of disfiguring abuse and the impairments it caused. Abolitionists felt that emancipation would heal the disabling effects of slavery.

Discussion Questions

- Nielsen (2012) argues that the language of disability was used to justify chattel slavery. How did the language of the abolitionists contribute to assumptions about people with disabilities?

- How does the intersection of disability and race in the context of chattel slavery challenge or complicate traditional narratives of both disability history and African American/Black history?

- What are the long-term effects of the narratives created by abolitionists on the perception of African Americans and people with disabilities today?

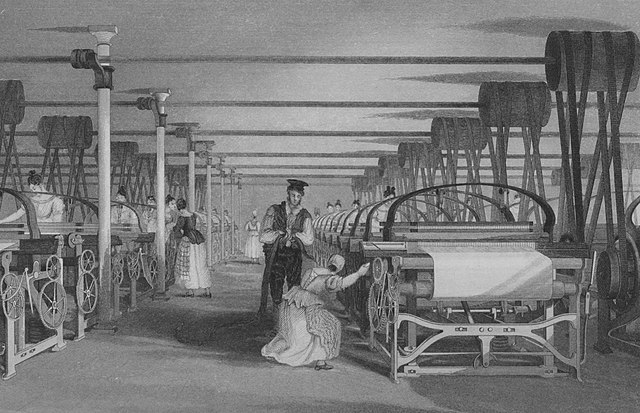

The Industrial Revolution (1780-1870)

The Industrial Revolution changed how people worked in the United States. This included people with disabilities. Industrialization brought about mass production, which relied on able-bodied workers who could work long hours under poor working conditions. These conditions often excluded those with any mental or physical limitations (Fox & Marini, 2024). Individuals with disabilities had previously been able to work from home. However, they could not access the industrialized working environment in the same way. Nielsen (2012) describes this well:

The regulation and standardization of industrialization…had made it more difficult for people with impairments to earn a living. A young woman unable to walk had easily worked in her family’s shoemaking industry. She could not, however, continue to make shoes as shoemaking slowly transferred from home industries to the factories of New England. She would not be able to live in the inaccessible dormitories available to female factory workers…she would not be able to walk the distances demanded of her; nor would other factory workers be as willing as her family members to make food available to her nearby her residence or aid in emptying her chamber pot. (p. 74)

In addition to changing work environments, industrialization led to an increase in individuals with acquired disabilities. Accidents were common in the fast-paced workshops, and workers had no legal protections. Generally, when individuals were injured, they were fired and lost their ability to make a living. Employees could sue. However, they typically lost based on the assumption that the accident was negligence by themselves or their coworkers (not the company) and that they knew the risks when they took the job (Fox & Marini, 2024).

The public school system rose out of industrialization, and the industrialized “one size fits all” workplace format of the industrial period is also what public schools in the United States were modeled after. Thus, children with disabilities experienced a similar shift in their day-to-day experience as their adult counterparts as schools emulated the work environment (Schrager, 2018). Many argue that this experience of building public schools during industrialization has continued to impact how schools are run today.

Discussion Questions

- How did the rise of industrialization influence the development of the public school system in the United States? What aspects of the industrial workplace were emulated in the school environment?

- What are the potential benefits and drawbacks of an education system modeled after industrial workplaces? How do these aspects specifically affect students with disabilities?

- What are some alternative education models that challenge the traditional industrial approach? How might these models better serve students with disabilities?

The Civil War 1861-1865

Much like the Revolutionary War, the United States Civil War had significant consequences around the experience of disability. While people were more likely to die than survive substantial injury at the time, some did survive, and again, war brought about the need for wounded soldiers to return home. Pensions continued to be expanded for veterans, and homes were established for returning soldiers who needed care. In addition, the advent of photography meant that veterans with disabilities were more visible to the public (Nielsen, 2012).

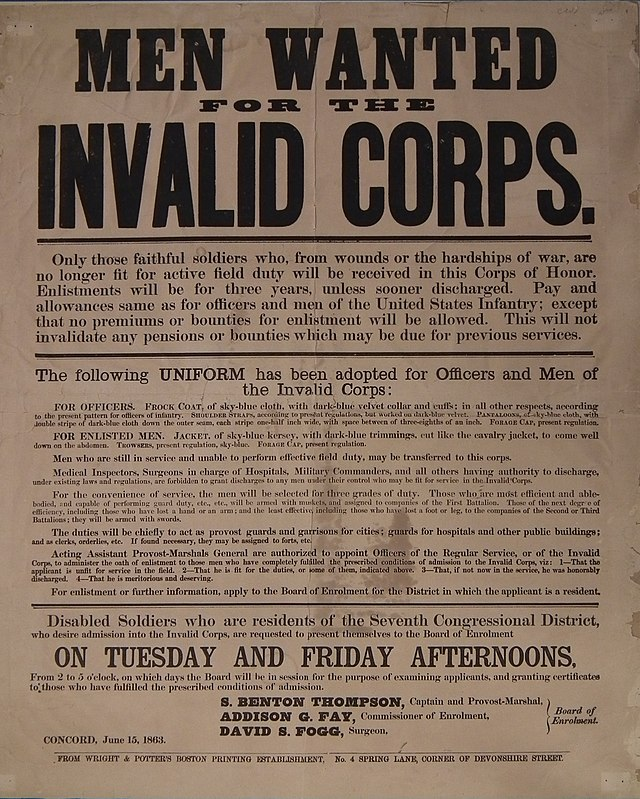

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln established the Invalid Corps. The Invalid Corps was meant to release able-bodied men from more menial tasks by giving those tasks to disabled veterans. This allowed able-bodied men to return to the front lines. Tasks included guarding prisoners, warehouses, and railways; enforcing the draft; supply runs; cooking and cleaning; clerical work; and marching in parades. The Invalid Corps was renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps in 1864 to boost morale as the initials IC were also used for rotten food stamped as “Inspected-Condemned.” This, plus discrimination against people with disabilities, led to ridicule of the men in the Invalid Corps. Despite the intention that the Invalid Corps would not fight on the front lines, many ended up in battle as a part of their service (McQuade, 2023; Nielsen, 2012).

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the Invalid Corps is not commonly taught in history classes?

- How might the Invalid Corps have fit into the narrative of disability at the time? How does it fit into the narrative of disability that we have today?

Many Black soldiers also fought in the Civil War and acquired disabilities from their service. However, due to racism, it was much more difficult for Black soldiers to receive the pensions owed them. Often, they had to travel long distances to apply for the pensions. Once they did this, they also needed to be literate enough to fill out extensive forms or find someone to do it. Even if they overcame these obstacles, the agents who managed the programs were overtly racist and denied claims regularly (Nielsen, 2012).

The Progressive Era to the New Era (1890-1927)

The late 1800s and early 1900s brought new experiences to those with disabilities. As the 1800s ended, the polio epidemic was in full swing. Not only did people who were already disabled acquire polio, but people who did not previously have a disability became disabled from the disease. Institutionalization, family structure, and the social perception of people with disabilities were all influenced by the polio epidemic. In addition, eugenics, forced sterilization, and institutionalization became prevalent issues in the disabled community.

The first wide-scale epidemic in European settlers in the United States was the polio epidemic of 1916. Polio left many people disabled, particularly those who had it as children, as it causes paralysis and weakness in muscles. Many children were removed from their homes and institutionalized due to polio and its aftereffects. This often led to the formation of a community among survivors.

Discussion Questions

- How do you think the polio epidemic changed public perception of disability?

- In some ways, the polio epidemic created community amongst survivors; in other ways, it ripped families apart when children/family members were institutionalized. How do you think this experience impacted the families left at home and their view of disability?

Eugenics and Forced Sterilization

The eugenics movement started in the early 1900s and continues to be a concern for disability rights today. Eugenicists of the early 1900s argued that success was genetic and that selective breeding would lead to a superior race of humans. The eugenics movement of the 1900s was spurred by the popularization of Darwin’s theory on the survival of the fittest and the rise of formalized medicine as doctors began to philosophize on the origins of illness and disability. Proponents of the eugenics movement believed that people who were wealthy and successful should have children to propagate successful humans, and those who were poor and disabled should not (Fox & Marini, 2024). The advent of salpingectomy (tying tubes in women) and vasectomy combined with eugenics led to the forced regulation of individual reproduction in the United States (Nielsen, 2012).

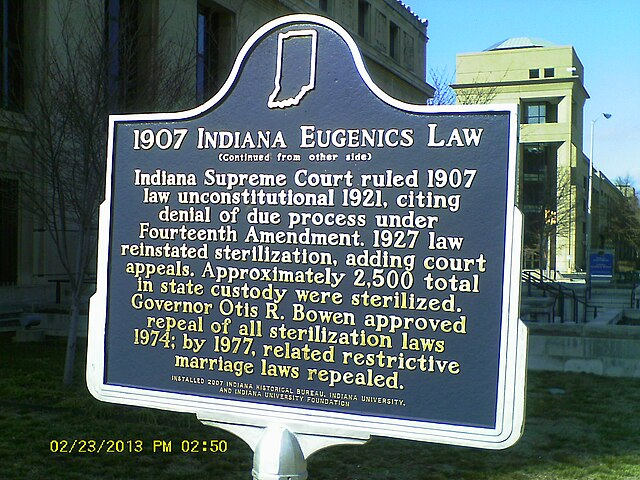

In 1896, Connecticut was the first state to forbid people with disabilities to marry or have sexual relations, and other states followed suit. Public support for these laws was high, and they soon expanded into forced sterilization. The first sterilization law was passed in Indiana in 1907. By 1926, 24 states had sterilization laws on the books. Of these states, 17 still had forced sterilization laws well into the 1980s. It is estimated that by 1950, 60,000 people had been forcibly sterilized in the United States (Fox & Marini, 2024).

World War II significantly impacted the public perception of eugenics in the United States. Once America took sides in the war, Nazi Germany was seen as barbaric and something to rally against. The Nazis murdered an estimated 300,000 German citizens who were deemed disabled throughout World War II, and eugenics as an overt science fell out of fashion in the United States as people began to associate eugenics with Nazi concentration camps (Fox & Marini, 2024). Despite this change in public perception, forced sterilization and reproductive justice continue to be a conversation in the disability rights movement to this day (National Women’s Law Center, 2022).

Ugly Laws were enacted to keep unsightly beggars and people with apparent deformities and scarring off the streets of cities in the United States. The first Ugly Law was passed in San Francisco in 1867. Other western states followed, and these laws became common in many states (Fox & Marini, 2024). The last arrest for an Ugly Law violation was in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1974, when a homeless man was arrested for having scars. The arrest was not prosecuted (Manoukian, 2023).

Discussion Questions

- What do Ugly Laws and eugenics have in common?

- From a social justice perspective, how do Ugly Laws highlight issues of discrimination and marginalization? How did these laws perpetuate inequality and social exclusion?

- How did Ugly Laws intersect with other forms of discrimination, such as those based on race, gender, or socioeconomic status? Discuss the compounded effects of multiple forms of marginalization.

- Can you identify any modern policies or social attitudes that resemble the discrimination perpetuated by Ugly Laws? How do these contemporary issues continue to affect people with disabilities?

The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

The stock market crash of 1929 started the biggest economic downturn in United States history—the Great Depression. Banks failed, and the life savings of millions of Americans were lost (SSA.gov, n.d.). The eugenics movement continued to impact the lives of those with disabilities as eugenicists shifted their argument to economics instead of genetics as jobs became scarcer (LEAP, n.d.). People with disabilities were again seen as worthless and a burden. In addition, people with disabilities faced crushing unemployment rates, with some estimating it to be more than 80 percent (Rosenthal, n.d.).

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) was elected president in 1932. FDR believed that the federal government needed to rescue the American people from the Great Depression. He implemented policies known as the New Deal, which encompassed bank reform, agricultural programs, emergency relief, work relief, union protection, social security, and programs for tenant and migrant farmers (Library of Congress, n.d.). Many programs brought about by the New Deal excluded people with disabilities. This exclusion led to some of the first advocacy protests for disability rights in the United States (Nielsen, 2012).

Did you know we had a president with a disability? FDR had post-polio syndrome and was paralyzed from the waist down. This was hidden from the public because he did not want to be seen as weak. Interestingly, even the Press Corps and those closest to him, such as Secret Service agents, conspired to hide the extent of his disability, and there were only two times during his presidency that he was shown as clearly disabled (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Discussion Questions

- Were you aware of FDR’s disability? Why do you think FDR’s disability was not emphasized during his presidency and beyond?

- The eugenics movement and discrimination towards people with disabilities was at an all-time high during the Great Depression. How do you think someone with a disability was able to be elected president during these times? What factors may have contributed to this?

As the United States entered World War II in 1941, there was a need to fill jobs as able-bodied men left to fight overseas. Many women stepped up to work during this time through the popular Rosie the Riveter campaign. Less well known is that the employment of people with disabilities surged during this time, as well. By 1945, 300,000 individuals with disabilities were placed through government agencies in workplace settings. By 1950 that number was almost 2 million (Nielsen, 2012).

Workplace accidents also increased during this time. The increased pace of industry was dangerous to workers, who were often undertrained and overworked. Speed was often more important than safety, and many were disabled in industrial accidents during World War II. Nielsen (2012) suggests it was safer to be on the battlefield during this time than to work in industry on the home front.

Many goods were rationed during World War II, including gas and rubber for tires. Early advocates for individuals with disabilities argued that rationing unfairly impacted those who could not access public transportation, such as those with physical disabilities. People who relied on personal transportation to get to work and other commitments found themselves suddenly stuck and unable to receive accommodation. This rationing then excluded individuals with disabilities from filling much-needed jobs during World War II (Nielsen, 2012).

Discussion Questions

- How might rationing have impacted people with disabilities more than those without?

- How might the experience of rationing be different for people with disabilities in the current day? How might it be the same?

- Compare this experience of people with disabilities during World War II to that of people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

World War II also impacted the institutions housing people with disabilities. Many institutions faced staffing shortages and crises as staff left to fight in the war. Men went to war, and women left to fill their jobs in factories and other arenas (Nielsen, 2012). Nielsen goes on to say that:

At the same time, the federal government sought placements for the nearly twelve thousand World War II conscientious objectors assigned to public service. Nearly three thousand were assigned to state mental hospitals and training schools containing an array of people with cognitive and developmental disabilities. (p. 144)

These conscientious objectors found harsh working conditions, long days, and severe abuse of the patients they were charged with caring for. This led many to speak out against the conditions of institutions. They reached out to community leaders, the media, academics, and other influential Americans with a plea to improve institutional conditions. The influence of media, including photographs, brought the brutality of institutionalization to the masses (Nielsen, 2012).

Both World War I and World War II resulted in soldiers returning home with disabilities. As these soldiers were seen as war heroes, there was support for rehabilitation and support for them as they were disabled while serving the United States. Both wars led to advances in rehabilitation and technology and more government funding for such developments (Anti-Defamation League, 2024).

Discussion Questions

- Is there a bias toward acquired disability versus a congenital one in our society? Why?

- What are the implications of war equating to a surge in advances in disability technology and rehabilitation? Discuss.

- Do we perceive veterans who have acquired disabilities differently than those who acquired disabilities outside of war? Why?

Vocational Rehabilitation

The concept of vocational rehabilitation was born out of war. Soldiers from both World Wars I and II had come home disabled, and society felt a need to support them as heroes. This support led to the Smith-Hughes Vocational Education Act in 1917 and the Smith-Sears Veterans Rehabilitation Act in 1918. Both acts provided funding for veterans’ training, jobs, and follow-up services. In 1920, the Smith-Fess Act established federal vocational rehabilitation for civilian citizens (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Despite the passing of vocational rehabilitation acts for soldiers, soldiers found accessing services to be complicated. This led to the formation of advocacy groups. One of the largest and most prominent was the Disabled American Veterans of the World War (DACWW), which advocated for veterans with disabilities. The DACWW lobbied to disassociate soldiers needing vocational rehabilitation and civilians. Thus, the legislation that was passed in the 1920s through the 1940s was separate for disabled civilian citizens and veterans.

Discussion Questions

- FDR advocated for rehabilitation to include both soldiers and civilians and the DACWW rallied against this. What are the two sides to this argument?

- Why might it make sense to combine soldiers and civilians? Why might it not?

By the 1920s, vocational rehabilitation had taken hold for civilians and soldiers. While some laws separated specific rehabilitation services for veterans, public support was in favor of vocational rehabilitation for all. While this was an advance in the experience of individuals with disabilities, attitudes towards individuals with disabilities were often paternalistic. People with disabilities were not given choices but instead were told what to do by vocational rehabilitation specialists who claimed they knew better and could guide their clients in the right direction. Client choice and self-determination were not a part of the early rehabilitation experience (Fleming et al., 2024).

In 1935, FDR signed the Social Security Act into law. Initially, it only provided benefits to the elderly. However, as paradigms started to shift, legislators began discussing how to support individuals with disabilities as well. In 1950, it was expanded to include individuals over 55 with a disability, and in 1960, the age requirement for people with disabilities was dropped altogether (Reed, n.d.).

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the first version of the Social Security Act only provided benefits to the elderly? Do some research on this.

- Subsequent expansion has made Social Security one of the most likely ways for individuals with disabilities to receive income if they are not working. What do you know about this process and how it works? Is it fair to individuals with disabilities?

- What are the current implications of receiving Social Security benefits as an individual with a disability?

In 1944, Dr. Howard Rusk opened the first medical rehabilitation facility for veterans—the Air Force Rehabilitation Center at Pawling, New York. Dr. Rusk had spent time with airmen and discovered that disabled veterans needed more than job training. Dr. Rusk found that airmen needed holistic care, such as emotional, educational, and social support, including working with families to ensure integration back into the family system. At the time, Dr. Rusk was ridiculed by his medical peers for delving into social services. That said, Dr. Rusk is now credited with beginning the consumer-driven movements that followed, such as the Independent Living Movement (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

The Post-War United States (1945-1968)

Following the Depression and World War II, many parents still found themselves being pressured to institutionalize their children with disabilities. However, in the 1940s, Laura Blossfield, a parent of a child considered to be “mentally retarded” (Nielsen, 2012, p. 142), reached out to fellow parents and began to network. As time went on, more parents banded together. In addition, famous people spoke out, arguing that children with cognitive disabilities were not a punishment from God. These roots of advocacy culminated in the National Association for Retarded Children, which formed as a merger of multiple local groups into a national group in 1952. By 1974, the organization had changed its name to the National Association for Retarded Citizens. And in 1992, the organization, still active in disability rights, changed its name to The Arc (Nielsen, 2012).

Major Disability Legislation

After the Civil Rights movement, the Disability Rights movement emerged. People with disabilities fought for equal rights to live independent lives with dignity and freedom of choice. As awareness grew about the challenges faced by disabled individuals, there was a demand to safeguard their rights through laws and legislation. Over the past 50 years, several important pieces of legislation have played a key role in shaping the protections that exist today.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on disability in any federally-funded program. It has multiple sections. Section 501 protects federal workers with disabilities from discrimination. Section 503 prohibits employers with federal contracts from discriminating against applicants or employees and requires that they actively hire people with disabilities as an affirmative action provision. Section 504 prohibits discrimination by any program that receives federal funding. Section 508 addresses information technology.

Section 504

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act is the most cited and has two primary purposes. Section 504 was intended to grant educational access to children with disabilities and to protect people with disabilities from discrimination. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act requires schools receiving federal funds to assess and accommodate children with disabilities. If a disability is identified, the school must provide appropriate services and support to that student. All of this happens at no cost to their parents or families. Essentially, schools are required to meet the needs of disabled children the same way that they meet the needs of any other child. This is done through a 504 Plan, which outlines the required services to remove disability-related barriers (Lee, n.d.).

The second piece of section 504 prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in any program or activity that receives federal funding. Thus, Section 504 covers places like national parks, hospitals, universities, and airports if they receive federal monies (Lee, n.d.).

Interestingly, President Nixon vetoed the Rehabilitation Act twice over funding disagreements. There was a fundamental disagreement about the federal government’s role versus state/local governments in providing funding to support the added costs of educating children with additional learning needs. During the 1970s, this disagreement led to multiple protests in the disability rights movement (Heumann, 2020).

The IDEA Act

The U.S. Department of Education (2023) estimated that in 1970, only 1 in 5 children with disabilities received public education. In addition, they reported that many states had discriminatory laws excluding children with a variety of disabilities from attending school. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA; Public Law 94-142) was signed into law in late 1975. This legislation guaranteed free and appropriate public education to any child with a disability in the United States. According to the U.S. Department of Education, “In the 1976-77 school year, 3,694,000 students aged 3 through 21 were served under the EHA” (para. 18). The U.S. Department of Education states that the purposes of the EHA was:

- to assure that all children with disabilities have available to them…a free appropriate public education which emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs,

- to assure that the rights of children with disabilities and their parents…are protected,

- to assist States and localities to provide for the education of all children with disabilities, and

- to assess and assure the effectiveness of efforts to educate all children with disabilities. (para. 15)

In 1986, Part C of EHA was added. Part C provided a grant program for early intervention services for children ages birth to three. Children identified with developmental delays or disabilities and their families work with a team to develop an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). The EHA required Local Education Agencies to conduct Child Find activities, which involve identifying, locating, and evaluating children with disabilities, to raise awareness of the availability of early intervention programs and evaluations in the community. Due to the evidence supporting the effectiveness of early intervention, new parents must be made aware of what to do if they have concerns about their child’s development before they are kindergarten-aged (U.S. Department of Education, 2023).

In 1990, the EHA was reauthorized and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The reauthorization of IDEA provided services for children identified with special learning needs from birth to 21 years old. This reauthorization also added brain injury and autism as coverable disabilities to the legislation. It mandated Individualized Educational Programs (IEPs) and Individual Transition Plans (ITPs) in schools (U.S. Department of Education, 2023).

Before the passage of the EHA in 1975, most children with disabilities were educated in separate classrooms and, often, separate schools. Thus, children with disabilities were not allowed to have contact with nondisabled peers in an educational setting. This segregation limited their ability to develop age-appropriate social and academic skills. When the EHA was renamed IDEA in 1990, the legislation identified this as a concern and required school-aged children with an identified disability to be educated in the least restrictive environment (LRE). Thus, children with disabilities now have the right to be with their same-aged peers if their IEP team determines that is the LRE for that learner. This shift in educational practice created a momentous shift in how children with disabilities are served in the classroom. Because of this legislation, children with disabilities are allowed to attend and participate in their local public school classrooms (Lambert, 2008).

Having children with a wider variety of educational needs in the same classroom had positive impacts on learning for all students—both disabled and non-disabled. However, it also challenged educators to adequately meet the needs of all students, particularly students with moderate to severe disabilities. Numerous research studies show that the impact of teacher and administrator perception on the successful inclusion of a child with a disability is a critical factor (Lambert, 2008). Thus, some of the success of inclusion lies in the attitude of those teaching the students. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Education (2022) noted that children ages 5–21 who received special education services in inclusive classrooms was 64.8 percent. This is a significant increase from 2000, when the percentage was 46.5 percent (Cole et al., 2021; National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

Though progress with inclusion has been made in the last 20 years, many children are still educated in segregated settings. Disability advocates continue to work toward acceptance from the broader public that people with disabilities belong in all places and spaces, including the public school classroom.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is a landmark federal civil rights law that established comprehensive civil rights protections for individuals with disabilities. Prior to the ADA, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited discrimination based on disability within programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. While Section 504 was groundbreaking in setting a precedent for disability rights, its scope was limited to federally-funded entities (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

In addition to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, various state laws and provisions from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided some protection for people with disabilities prior to 1990. However, there was no unified federal legislation specifically guaranteeing civil rights to people with disabilities. The ADA expanded upon the foundation laid by Section 504, becoming the first comprehensive federal law to ensure equal opportunities and prohibit discrimination based on disability in a wide range of areas, including employment, public services, public accommodations, transportation, and telecommunications (Fleischer & Zames, 2011). The ADA has multiple sections:

Title I—Employment. Title I applies to any employer with 15 or more employees and requires employers not to ask about disability status when interviewing a potential employee. It also requires reasonable accommodation for employees with disabilities and equal access to recruitment, hiring, pay, training, and promotion.

Title II—State and Local Government Activities. Requires that state and local governments provide equal access to people with disabilities. Entities covered include public education, places of employment, transportation, recreation, health care, social services, justice services, and voting. Title II includes architectural standards in new construction for accessibility and reasonable accommodation for people with disabilities receiving services. Title II also covers public transportation such as city buses, railways, and subways.

Title III—Public Accommodations. This section of the ADA stems from the Civil Rights Act and prohibits discrimination based on disability in any public business or service. Title III states that any building built after January 26, 1993, must be accessible, and any older building needs to make any accessibility changes that are “readily achievable” (Fleischer & Zames, 2011, p. 96).

Title IV—Telecommunications and Relay Services. This section of the ADA addresses access to telephone and television for people with disabilities and established interstate and intrastate telecommunication relay services such as TTY for Deaf individuals. Title IV also requires closed captioning of any federally funded public service announcements (ADA.gov, 2020; Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Video: How the ADA Changed the Built World

Discussion Questions

- How has the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) changed the physical environment and accessibility of public spaces since its enactment in 1990?

- What role did advocacy and activism play in the passage of the ADA?

- Despite the ADA, what ongoing challenges do people with disabilities face in accessing public spaces and services? How can these be addressed?

- Compare the impact of the ADA with other civil rights legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. How do these laws collectively work to promote equality?

The Disability Rights Movement

Disability rights movements have been active since the 1930s. One of the first advocates for disability rights was Dorthea Dix, who famously exposed the horrific experiences of people with disabilities in institutions in the 1840s and 1850s. Dorthea Dix impacted legislation at the state level but fell short of her goal of establishing federal funding to fix the systems of institutions (Disability History Museum, n.d.). In addition to Dorthea Dix, there were other pioneers in disability rights early on, such as Elizabeth Ware Packard, Agatha Tiegel Hanson, and Helen Keller.

Eunice Kennedy (Shriver) was one of the nine Kennedy children of Rose and Joseph P. Kennedy. Of the nine siblings, many went on to influential social and political roles, including a future president of the United States (John F. Kennedy) and two future U.S. Senators (Edward and Robert Kennedy). The Kennedy’s oldest daughter, Rosemary, had an intellectual disability. In 1941, she underwent a lobotomy organized by Mr. Kennedy, but without her mother’s knowledge. This procedure had disastrous consequences. After the procedure, her self care skills deteriorated to that of a toddler despite being in her early 20s. Rosemary was institutionalized and disappeared from family life. She would live in an institution for the next six decades. Eunice was closest with Rosemary throughout her life and tried to support her sister. Eunice and her other sister, Jean Kennedy Smith, became lifelong supporters of people with intellectual and physical disabilities. Eunice founded the Special Olympics. She believed sports could unite everyone (Special Olympics, n.d.). Jean founded Very Special Arts, an organization that helped people with intellectual disabilities access the arts (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum, n.d.).

Discussion Questions

- How did Rosemary Kennedy’s condition affect the dynamics within the Kennedy family? What role did her family play in her care and public representation?

- How does Rosemary Kennedy’s story compare to other prominent individuals with disabilities in history? What similarities or differences can be observed in their experiences and societal responses?

- What kind of support can the Special Olympics provide to people with disabilities? Is this inclusive, or does it exclude people with disabilities?

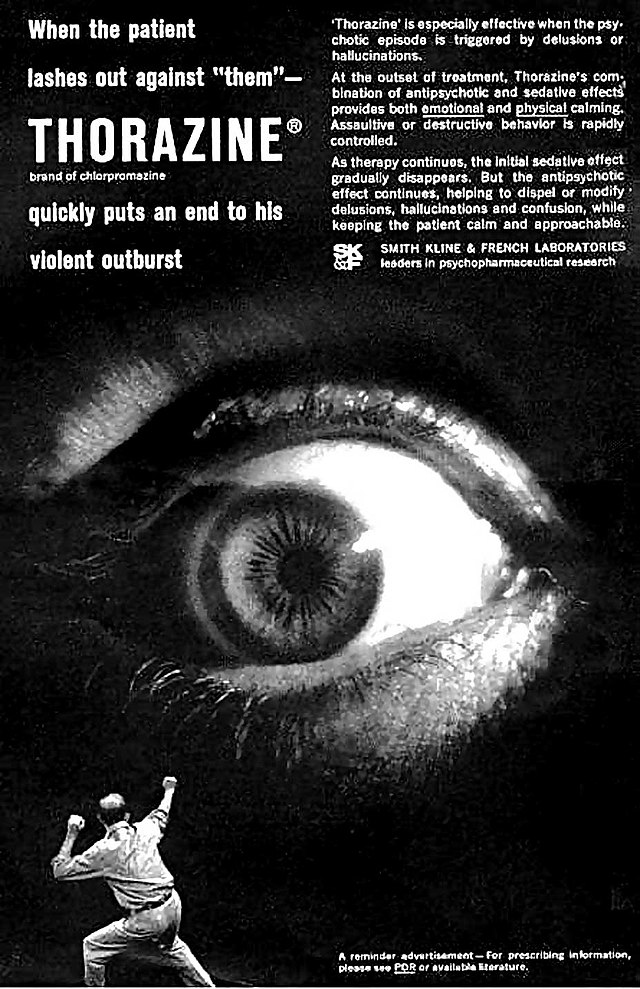

There was a lull in disability rights activism in the 1930s and 1940s, probably due to the polio pandemic as well as the two World Wars. However, by the late 1950s and early 1960s, disability was back on activists’ radars as the shift toward deinstitutionalization began. This shift was brought on by advancements in medical science and the introduction of the first effective antipsychotic medication in 1955, Thorazine (Torrey, 1997). With these advancements, a movement toward transitioning people with mental health issues out of institutions and back into the community started. Torrey (1997) states:

The magnitude of deinstitutionalization of the severely mentally ill qualifies it as one of the largest social experiments in American history. In 1955, there were 558,239 severely mentally ill patients in the nation’s public psychiatric hospitals. In 1994, this number had been reduced by 486,620 patients, to 71,619. (para 3)

Torrey goes on to say that most of the individuals released from institutions in the 1950s and 1960s had severe mental illness and estimates that 60% of those individuals were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

In addition to individuals with mental health diagnoses being deinstitutionalized, individuals with physical disabilities who were living in institutions were also impacted by deinstitutionalization. In 1958, Anne Emerman asked to go to college following high school and was a “test case” (Fleischer & Zames, 2011, p. 33) for deinstitutionalization from Goldwater Memorial Hospital in New York City. Emerman had an acquired physical disability from polio and was a wheelchair user. Emerman went on to receive a master’s in social work, start a family, and work in the mayor’s office on disability. Emerman also became a significant figure in the disability rights movement (Fleischer & Zames). She died on November 3, 2021.

Marilyn Saviola was a disability rights advocate who lived at Goldwater Memorial Hospital. When she was not allowed to move from the facility, she advocated within the facility for a separate ward for young adults. The ward looked more like a dorm, and social connections were made between residents. Saviola advocated for herself to attend college and became the first person to do so while institutionalized at Goldwater. Saviola went on to leave the institution in 1973. In 1983, she became the executive director of the Center for Independence of the Disabled in New York City, founded in 1978 and the first independent living center in New York State.

Discussion Questions

- What can current institutions learn from what Saviola did at Goldwater?

- Saviola talked about having to continue to live at a poverty level to maintain her benefits. This contributed to her ability to work or not work. How might this continue to be an issue today?

Edward Roberts and the Independent Living Movement

Accessibility on college campuses was one of the first issues in the 1950s and 1960s to spur the disability rights movement. There had been several small victories on college campuses; however, Edward Roberts’ experience at the University of California, Berkeley, is often cited as the start of the independent living movement. Roberts was disabled by polio at the age of 14 and used an iron lung. Due to this, he completed high school from home. He then decided he wanted to go to college. He chose the University of California, Berkeley, to get his degree in political science. They did not agree to admit him, so in 1962, Roberts sued the University of California, Berkeley, for admission. He was successful (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

At the University of California, Berkeley, Roberts lived at the Berkeley Infirmary at Cowell Hospital. His needs were met by orderlies doing public service to avoid military service in Vietnam. As time passed, more students in wheelchairs joined him at the hospital, and Berkeley became a haven for disabled students. Eventually, Roberts obtained a grant to help people with disabilities and began to work on political change at the college. Roberts and other students formed a political group called the Rolling Quads. The Rolling Quads were a disability pride group that advocated for independence on the college campus by decreasing physical barriers and increasing self-reliance (Nielsen, 2012). Through the advocacy of the Rolling Quads, the experience of being a disabled student on campus at Berkeley in the 1970s became one of inclusivity and access (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Roberts and other disability activists began to develop independent living centers nationwide. These centers focused on self-determination, consumer control, choice, and deinstitutionalization and provided services such as caregiving, wheelchair repair, counseling, legal assistance, training in self-advocacy, and community. In addition, the founders of the centers advocated for architectural and transportation accessibility for people with disabilities (Nielsen, 2012).

Roberts acknowledged the influence of other civil rights movements, such as the women’s rights movement, Native American activists, and the Black Power movement in his work. He saw connections between the disability rights movement and other civil rights movements. That said, he was often dismissed when trying to build connections with them (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Discussion Questions

- What connections do you think Roberts saw between the different civil rights movements and the disability rights movement?

- Why do you think he was shunned when he tried to work with other civil rights movements? How might they have seen Roberts and his movement as different from theirs?

- Do you think the disability rights movement is still shunned by some of the other civil rights movements, such as Black Lives Matter or #MeToo? Why might this continue to happen today?

Roberts earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science from the University of California, Berkeley. He was then appointed to a position at his alma mater. In 1975, he became the director of the State Department of Rehabilitation in California. He went on to have a career in disability advocacy, raising public awareness and lobbying throughout his life. Roberts died at the age of 56 in 1995 of cardiac arrest (Fleischer & Zames, 2011).

Influential Events and People of the 1960s and 1970s

The civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s significantly impacted the disability rights movement. Much like other movements, the disability rights movement began to coalesce nationally late in the 1960s. People with disabilities began to challenge the medical model of disability, which focused on hierarchical constructs of physical and mental fitness. Nielsen (2012) states:

The disability rights movement was energized by, overlapping with, and similar to other civil rights movements across the nation, as people with disabilities experienced the 1960s and 1970s as a time of excitement, organizational strength, and identity exploration. Like feminists, African Americans, and gay and lesbian activists, people with disabilities insisted that their bodies did not render them defective. Indeed, their bodies could even be sources of political, sexual, and artistic strength. (p. 160)

In 1968, the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) passed. This act required that all newly built buildings be accessible, and that accessibility be built into any new construction. However, this legislation had inconsistent implementation due to a lack of oversight and uniform accessibility standards (U.S. Access Board, n.d.). In addition, it paid no attention to public transportation, housing, recreational facilities, or any privately owned buildings. In general, the ABA was not seen as successful legislation, but it set the stage for the disability rights movement (Nielsen, 2012).

In the 1970s, there was a conversation in the United States government about where disability rights fit into the civil rights movement. In 1972, Senator Hubert Humphrey and Congressman Charles Vanik introduced legislation to amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include disability, which did not pass. However, the drafted language was taken and built into Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which is a critical part of that legislation today. Interestingly, when the Rehabilitation Act went up for discussion and debate in Congress and public hearings, only one person commented on Section 504’s anti-discrimination language (Nielsen, 2012).

The discussions surrounding the Rehabilitation Act and its two vetoes by President Nixon sparked protests from disability activists. Much like the ABA, the initial implementation of the Rehabilitation Act did not include enforcement or enactment. That had to be done by the head of the Health Education and Welfare (HEW) department in Washington, D.C. His name was Joseph Califano, and he showed little interest in advancing disability rights. He did nothing to move Section 504 forward. To combat this, disability advocates took 504 enactment to court. However, despite a judge saying that the government needed to move forward with enactment, nothing happened (Nielsen, 2012). As enactment stalled, protests began to erupt around the country. In April of 1977, disability rights activists worked together to stage demonstrations at HEW offices nationwide. Protests and subsequent sit-ins occurred in Denver, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles HEW buildings. In San Francisco, protesters occupied the HEW building for a 25-day sit-in (Heumann, 2020).

Judy Heumann, a disability rights advocate and woman with a disability, describes the experience of the 25-day sit-in at the HEW building in San Francisco in her memoir, Being Heumann (Heumann, 2020). Heumann led the protest with fellow disability rights advocate Kitty Cone, demanding that Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act be enacted. As the sit-in continued, the government turned off the hot water, refused to allow people or goods (including medicine) in and out of the building and cut the phone lines. Every time the government tried to cut access, the people protesting organized to manage the complex process of remaining onsite at the HEW building (Heumann. 2020).

The San Francisco protesters had multiple well-known supporters. Ed Roberts, who was running the California Department of Rehabilitation, gave a speech at the protest encouraging the implementation of Section 504. The Glide Memorial Church, under Reverend Cecil Williams, organized a vigil outside the HEW building to maintain visibility. Organizers in other movements, such as labor unions, churches, and civil rights groups, urged President Carter to end the protests and enact the legislation. The Butterfly Brigade, a gay rights group, smuggled walkie-talkies into the building when the phone lines were cut (Nielsen, 2012). On day three of the sit-in, the Black Panthers forced their way into the building and, in solidarity, brought hot food to the protesters daily. Twenty-four days after the sit-in started, the enabling regulations were signed in Washington, DC. The protesters spent one more night in the HEW building to celebrate and left the building on Saturday, April 30th, singing “We Have Overcome” (Heumann, 2020, p. 147).

Following the enactment of Section 504, disability advocacy became about implementing the law. Heumann (2020) points out that desegregation was a lot simpler in terms of implementation than the Rehabilitation Act and uses the example of access on a public bus. It is easy enough for Black people without disabilities to access the bus once the law changed, however those with disabilities need a different kind of structural changes, such as adding lifts to the bus, for access to occur (Heumann, 2020).

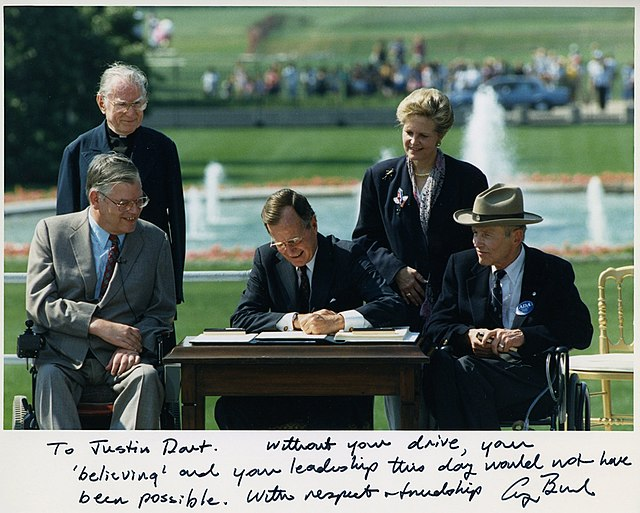

Video: Disabled Activists Crawl Up the Steps of the Capitol

The Capitol Crawl, which took place on March 12, 1990, was a powerful and symbolic act of protest led by disability rights activists, particularly those from the organization American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT). In a bold demonstration of the barriers people with disabilities face, protesters—many of whom used wheelchairs or other mobility aids—crawled up the steps of the U.S. Capitol building to highlight the lack of accessibility in public spaces, including government buildings. The Capitol Crawl played a crucial role in galvanizing support for disability rights and was instrumental in the eventual passage of the ADA, signed into law later that year on July 26, 1990.

Discussion Questions

- How did the Capitol Crawl serve as a turning point in the disability rights movement, and what role did it play in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)?

- What impact did the visual symbolism of the Capitol Crawl—particularly the image of people with disabilities physically crawling up the Capitol steps—have on public perception of disability rights and accessibility issues?

- In what ways does the Capitol Crawl highlight the tension between individual rights and societal responsibility in creating accessible public spaces? How can this protest inform current debates on accessibility and inclusion?

Current Issues in Disability

As many anticipated, implementing the Rehabilitation Act, IDEA, and ADA has been complex and intermittent. The Disability Rights Movement now clearly identifies itself as a civil rights movement and continues to advocate for the civil rights of individuals with disabilities. Issues that are currently being faced include but are not limited to funding, vocational rights, parental rights, reproductive healthcare, institutionalization, and physician-assisted suicide (Fleischer & Zames, 2011; Nielsen, 2012).

Video: The Changing Reality of Disability in America

Discussion Questions

- How does the video address shifts in societal attitudes towards disability? In what ways have these attitudes changed, and what factors have contributed to these changes?

- What are some of the ongoing challenges faced by people with disabilities despite progress made? How does the video suggest addressing these challenges?

- How has the information presented in the video changed your understanding of disability? What new perspectives or insights have you gained?

Ability Privilege and Ableism

Ability privilege refers to the experience of having privilege based on ability. In our society, people have advantages because they have abilities. Much like being White has certain privileges in our society, the experience of being traditionally able-bodied also carries privileges. Harveston (2019) states: “Able-bodied privilege, in a nutshell, means living under the assumption that everybody else on earth can speak, hear, see, and get around, more-or-less the same way we do, with a similar amount of ease.” (para 7). She goes on to state that: “Able-bodied privilege is less about who you are and more about the things you don’t have to worry about in life. And through no fault of their own, a lot of people have a lot more worries than others” (Harveston, 2019, para 8).

There are many examples of ability privilege, partly because there are many kinds of identified disabilities. Some examples include not having to consider the physical environment for a work or social event, being able to move freely away from uncomfortable things, being able to easily use credit card machines in the store, representation in the media, reproductive freedom, appropriate medical care, and housing access (Riolriri, 2009).

Article: Examples of Ability Privilege

Discussion Questions

- Have you ever considered yourself privileged because of ability? Why or why not?

- After reviewing this extensive list, what stood out to you? Why?

- Is there anything missing from this list?

In addition to ability privilege, the experience of living with a disability often involves regular and systemic discrimination. While accessibility is the law of the land, ask any wheelchair user about accessibility, and they will have an entirely different story to tell. As Sligh (2019) points out, there is a significant difference between accessible and disability friendly. Sligh has a daughter with a physical disability and gives examples of elevators in buildings. While they are often present, placement rarely makes sense. Thus, having to find and access elevators reinforces her daughter’s social isolation. She also points out that there is often an assumption of intellectual disability whenever there is an apparent physical disability present, which impacts her daughter in many ways (Sligh, 2019).

Is access a privilege, or is it a civil right? Niziolek (n.d.) argues that access to healthcare, in-home assistance, employment, housing, transportation, and marriage should not be considered a privilege for people with disabilities—they should be regarded as civil rights. This reframe is often met with resistance as there is a pervasive social attitude that people with disabilities should be grateful for the services they receive.

Video: Disabled Americans Are Punished for Getting Married

Discussion Questions

- How does reframing access from a privilege to a right change the conversation about disability access?

- Why might some people still see access for people with a disability as a privilege? Where does this attitude stem from?

- Do people with disabilities have the right to get married without it impacting their benefits? Why or why not?

In addition to discrimination, people with disabilities often find themselves faced with myths or stereotypes of disability. Examples of myths about disability include (a) that people with disabilities are somehow partial or not whole people; (b) that the successful disabled person is a superhuman triumphing over adversity; (c) that the burden of disability is unending, that the life of a disabled person is one of sorrow and sadness; (d) that the families of people with disabilities sacrificed nobly; (e) that disability needs to be fixed or corrected; (f) that people with disabilities are somehow a menace or dangerous to society; and (g) that people with disabilities are somehow innocent and endowed with some sort of special grace meant to inspire (Block, n.d.). Block goes on to point out that these stereotypes permeate the individual experience of being disabled in the United States, as well as impacting public policy and legislation.

Video: Inspiration Porn and the Objectification of Disability by Stella Young

Discussion Questions

- How does inspiration porn affect people with disabilities personally and socially? What are some potential psychological and emotional impacts?

- In what ways does inspiration porn contribute to or detract from social justice efforts for individuals with disabilities? How does it affect the broader goals of equity and inclusion?

- What are some positive and empowering ways to represent disability that avoid inspiration porn? How can media and advocacy shift towards more respectful and accurate portrayals?

- Have you seen/heard inspiration porn about people with disabilities? Where?

Deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization remains a concern for the disabled community. In many places, people with disabilities continue to be housed in group homes, nursing homes, and other congregate care facilities despite the deinstitutionalization movement. In addition, what is legally considered institutionalization versus what feels like institutionalization can be two very different things. For example, a nursing home is legally viewed as an institution in the State of Washington. However, an adult family home or assisted living is not. That said, clients often feel institutionalized in those settings, as well. For those who want to live in their own homes, funding for care can be complex and challenging to access. In addition, it often varies from state to state as most caregiving services are funded through Medicaid dollars. In some states, institutionalization is the only option for 24-hour care for individuals who need it (DaSilva, 2018). As an offshoot of the independent living movement, many current disability advocates focus on where individuals with disabilities live and receive services.

Video: How Health Care Makes Disability A Trap

Discussion Questions

- What are the pros and cons of different states treating people with disabilities differently?

- How do policies within the healthcare system contribute to the stigmatization of disability? What changes in policy could help mitigate this?

- What kind of policy change is needed to fix Jason DaSilva’s dilemma?

- What are some effective strategies for advocating for systemic change within the healthcare system to better support individuals with disabilities? How can individuals and organizations work toward reform?

- Is it fair that Jason DaSilva must live so far from his son because he cannot receive care? Is this discrimination? Why or why not?

Video: Institutionalized as a Teen with Jensen Caraballo

Discussion Questions

- Jensen Caraballo is talking about current day institutionalization—is deinstitutionalization failing?

- What kind of options are there for someone like Jensen Caraballo? What kind of options should there be?

The other side of the deinstitutionalization coin has been the lack of services available for people with disabilities in the community who need them. Access to caregiving and other healthcare services can be a significant barrier to success for people with disabilities who need personal care and other kinds of services. Staffing shortages, high staff turnover, and a lack of education often result in poor or absent care for people who need it.

Nielsen (2012) points out that historically, the individuals who were successful in deinstitutionalization were, and continue to be, those with privilege. Individuals with disabilities with strong family advocacy, financial resources, access to independent living centers, and access to well-run community group homes and community-based mental health centers have had positive outcomes from deinstitutionalization. However, those without financial means or familial support and advocacy have not had the same experience of deinstitutionalization. A lack of services for those without resources has led to mass incarceration of people with disabilities, particularly for those with mental health issues. Nielsen goes on to say, “The vast majority of those [people with disabilities] incarcerated are poor and people of color” (p. 164).