6 Race, Racism, and Being Black in the United States

Nikki Golden and Bernadet DeJonge

- The reader will be able to explain race as a social construct.

- The reader will be able to discuss racial identity theories and models.

- The reader will be able to identify the impacts of anti-Black racism in the United States.

- The reader will be able to connect systemic racism and current social justice movements.

- The reader will be able to identify historical events that continue to impact the lived experiences of Black/African American people in the United States.

Introduction

Addressing social justice requires persons living in the United States to acknowledge and confront systemic racism, which has played a significant role in perpetuating social injustice throughout the country’s history. The legacy of racial injustice, which stems from the genocide of Indigenous groups and the chattel enslavement of Africans, continues to affect people in the United States today. This chapter explores the social constructs of race and racism and examines the historical evolution of race in the United States from the perspective of people with African ancestry.

Throughout the chapter, we use the terms “Black” and “African American” interchangeably to honor how people of African descent choose to self-identify. “African American” typically refers to persons who have ancestral ties to Africa through the history of slavery and colonization in the United States. This term emphasizes geography and history: people whose ancestors were forcibly brought to the Americas as part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and who have since developed a distinct cultural identity within the United States. “Black” is a broader racial and cultural identifier that can include African Americans, immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean, and people from other countries around the world associated with Africa either phenotypically, culturally, or both—regardless of specific national or ethnic background.

Race as a Social Construct

Race is not biologically determined; instead, it is a social construct created by humans based on characteristics such as skin color, with specific value-laden categories emerging relatively recently in human history (Kendi, 2016). These categories carry profound social and political consequences shaped by historical power dynamics and cultural interpretations. In the early English colonies, before the establishment of fixed racial categories, religious affiliation often dictated social status (Wilkerson, 2023). Today, racial classifications are based on observable yet arbitrary physical characteristics, genetics, or cultural differences (Bonham, 2024; Burton et al., 2010). According to the National Human Genome Research Institute, race is defined as “a social construct used to group people” and “was constructed as a hierarchical system for classifying human groups, creating racial classifications that identify, distinguish, and marginalize certain groups across nations and globally” (Bonham, 2024, para 1). Despite the socially-constructed nature of race, racial categories in the United States are deeply ingrained, to the extent that even in the face of scientific evidence, “some human beings continue to perceive other human beings as excluded from the moral order of personhood” (Zimbardo, 2008, p. 307).

Furthermore, racial hierarchy in the United States can be explained as politically constructed, where “Whiteness” is deliberately positioned at the top of the hierarchy through laws, policies, and social practices designed to concentrate power, wealth, and privilege among those classified as White. This system was historically codified through slavery, segregation, discriminatory housing policies, unequal education, and biased criminal justice practices. This hierarchy was not natural or inevitable, but was deliberately created to justify exploitation and maintain power imbalances (Coates, 2015). In its simplest form, this hierarchy in the United States is typically framed in two distinct parts understood to be mutually exclusive and opposing: White and not White (Rosenblum & Travis, 2016). While significant legal progress has occurred, this historical ordering continues to shape contemporary society through persistent wealth gaps, residential segregation, educational disparities, and implicit biases in institutions.

Because race is a social construct, categorical definitions have been fluid, with determining factors based on need versus fact (Burton et al., 2010). An example is the Latinx population, which was considered White well into the 20th century. The category of “Hispanic” was adopted by the United States government for the first time in 1980 (Simon, 2024). But Hispanic or Latinx is considered an ethnicity, not a race. Thus, one can be Hispanic on the United States Census and be of another race, such as White or Asian (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). Kendi (2016) argues that racial categories in the United States were created for political and economic gain: “European cultural values and traits, and hierarchy-making was wielded in the service of a political project: enslavement” (p. 83).

Racial Identity in the United States

Racial identity is how individuals understand and define themselves in relation to their racial group. It also incorporates how society assigns meaning to these groups. Racial identity is shaped by historical, cultural, and social contexts and influenced by experiences of discrimination, privilege, and power. For racialized groups, identity often forms through encounters with prejudice and societal expectations, leading individuals to develop coping or resistance strategies (Tatum, 2017). In contrast, individuals from dominant racial groups may experience their racial identity with less awareness of its influence, recognizing it primarily in moments of racialized tension (DiAngelo, 2018). Racial identity is not static; it evolves over time and can shift based on personal experiences and social interactions. Socially constructed identities such as race are critical factors in predicting life outcomes, including education, income levels, health and healthcare, and access to other resources. Understanding how people form and express their racial identity is crucial to addressing racism, inequality, and social justice.

Racial Identity Theories

Theories such as Social Identity Theory, Critical Race Theory, and Racial Identity Development models provide frameworks for understanding how individuals understand and negotiate their racial identity within society. The concept of Double Consciousness and the framework of Intersectionality further enrich our understanding by highlighting the internal and multifaceted nature of racial identity. These theories collectively emphasize that racial identity is not just about how individuals see themselves, but also about how they are perceived and navigate a society deeply influenced by race and racism.

Double Consciousness

Double Consciousness was introduced by W. E. B. Du Bois in his seminal work The Souls of Black Folk (1903). It is a critical historical concept in any discussion of racial identity. Double Consciousness refers to the internal conflict that African Americans (and, by extension, other marginalized racial groups) experience as they negotiate their identity in a society that devalues their race. Du Bois describes it as a kind of psychological division where individuals are constantly aware of how they are perceived by the dominant, often oppressive, group and how they view themselves (Gingras, 2010).

Double Consciousness encompasses several key points. First, the concept of a dual identity involves racialized individuals’ awareness of themselves from both their personal perspective and the perspective imposed by a society dominated by Whiteness. This awareness often leads to internal conflict and tension, as individuals struggle to balance their personal sense of identity with the need to conform to or negotiate societal expectations and stereotypes. Additionally, the struggle of Self-Perception vs. External Perception captures the difficulty of reconciling one’s self-view with how one is perceived and judged by others. This complex interplay highlights the internal and external struggles inherent in managing dual aspects of racial identity in a society organized around race (Du Bois, 1903).

Social Identity Theory

Henri Tajfel and John Turner proposed Social Identity Theory in the 1970s. According to this theory, individuals derive part of their self-concept from membership in various groups, including racial groups. Tajfel and Turner argued that social identity provides individuals with a sense of belonging, purpose, self-worth, and identity. Additionally, the tendency to categorize, identify, and compare with other groups influences an individual’s experience of social identity (McLeod, 2023). Social Identity Theory is responsible for introducing the concepts of in-group and out-group, which are frequently used in psychology to explain biased behavior. Criticisms of Social Identity Theory include an overemphasis on group identity, overly simplistic study environments, lack of focus on individual differences, neglect of power and structural factors, and insufficient explanations for why people sometimes favor out-groups (Brown, 2000; Ellemers et al., 2002; Hogg & Abrams, 1990; Jost & Banaji, 1994; Reicher & Haslam, 2006).

Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory (CRT) explores the intersections of race and racism with other forms of social stratification, such as social, legal, and institutional structures. Originating in the late 1970s and 1980s from the work of legal scholars like Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Richard Delgado, CRT emerged as a response to the inadequacies of traditional legal approaches in addressing racial injustice. CRT recognizes racism as systemic and underscores that racism is embedded in United States law, policy, and practice. CRT emphasizes intersectionality and the social construction of race, and it places value on the lived experiences of those subject to racism. Additionally, CRT challenges colorblindness and gradualist change, instead advocating for large-scale systemic power shifts through a social justice lens (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017).

While some view CRT as a critical tool for understanding and dismantling systemic racism, others argue that it is incompatible with traditional religious or ideological beliefs, as exemplified by a statement issued by Southern Baptist church leaders in 2020. The six White male presidents of the Southern Baptist seminaries issued a joint statement against CRT as “incompatible with the denomination’s confession of faith” (Jones, 2023, p. 268).

However, in 2021, the Catholic order of the Jesuits “announced an initiative to raise $100 million to atone for their role in slavery and to benefit the descendants of the enslaved people they had once owned” (p. 267), with all funds placed in a foundation to be co-facilitated by direct descendants of enslaved people (as cited in Jones, 2023).

Discussion Questions

- What are the potential impacts of rejecting or embracing CRT on religious and educational institutions?

- What role should religious organizations play in addressing the legacy of slavery and systemic racism in the United States?

- How has the backlash against CRT from 2020 onward influenced broader discussions on race, history, and education in the United States?

- Given the racial tensions and protests of 2020, how should institutions, both secular and religious, approach the teaching of history and race in ways that promote healing and understanding?

Racial Identity Development Models

Racial Identity Development models seek to explain how individuals come to understand and internalize their racial identities. These models describe the stages that individuals experience as they grapple with the meanings, implications, and significance of race in their lives. They help explain how people move from racial unawareness to a more nuanced understanding of where their racial identity fits in societal power structures. Most models follow a pattern of a trigger event, exploration and searching, and internalization and acceptance. More recently, researchers have begun to study White identity and its development (Project Ready, 2016).

White Racial Identity Model: Janet Helms (1990)

This model describes the racial identity development of White individuals in the context of a racially stratified society. The stages are:

- Contact: Lack of awareness about racism and White privilege.

- Disintegration: Growing awareness of racial inequalities, leading to discomfort.

- Reintegration: Reaffirmation of racial privilege or denial of racism to reduce discomfort.

- Pseudo-Independence: Intellectual recognition of racism without fully confronting personal privilege.

- Immersion/Emersion: Active exploration of one’s own racial privilege and racism.

- Autonomy: Full acknowledgment of White privilege and active commitment to dismantling racism.

Biracial Identity Development Model: Walker S. Carlos Poston (1990)

This model accounts for the unique experiences of biracial or multiracial individuals. The stages are:

- Personal Identity: The basis for identity emphasizes personal characteristics rather than race.

- Choice of Group Categorization: Choice to identify with one racial group, typically due to external pressures.

- Enmeshment/Denial: Confusion or guilt about selecting one racial group over another.

- Appreciation: Increasing awareness and appreciation of the multiple racial heritages.

- Integration: Full integration and acceptance of a biracial or multiracial identity.

Nigrescence Model: William E. Cross (1991)

Focuses on African American racial identity and describes a process called nigrescence (the process of becoming Black), in which individuals move from a state of unawareness or devaluation of their Black identity to one of affirmation and pride. The stages include:

- Pre-Encounter: Lack of awareness of race or preference for dominant White culture.

- Encounter: Personal or social event that triggers awareness of racism.

- Immersion/Emersion: Immersion in Black culture and often a rejection of anything related to White culture.

- Internalization: Development of a balanced, secure sense of Black identity.

- Internalization-Commitment: Commitment to racial justice and Black empowerment.

Model of Ethnic Identity Development: Jean Phinney (1992)

Describes the ethnic identity development process for all racial/ethnic groups, including both minority and majority individuals. It outlines the following stages:

- Unexamined Ethnic Identity: Lack of interest in or awareness of one’s ethnic identity.

- Ethnic Identity Search: A triggering event that leads to active exploration of one’s ethnic background.

- Achieved Ethnic Identity: Formation of a clear, secure sense of one’s ethnic identity.

- How do Cross’s Nigrescence Model and Helms’s White Racial Identity Model compare in their depiction of identity development in relation to systemic racism? What are the similarities and differences in how each model addresses the impact of racial awareness on individual identity?

- How do the stages of racial identity development in Helms’s White Racial Identity Model and Cross’s Nigrescence Model reflect different aspects of privilege and oppression? What insights can be gained by comparing the processes through which White individuals and African American individuals come to understand their racial identities?

- In examining how individuals move through stages of identity development, how might Cross’s Nigrescence Model and Poston’s Biracial Identity Development Model provide complementary perspectives on forming racial identity in response to social and personal experiences?

- Most of these models were generated in the 1990s. Why might that be? What current theories or movements are out there that describe racial identity development?

Video: How Can I Have a Positive Racial Identity? I’m White!

Discussion Questions

- What are the central themes explored in the video regarding White identity? How does the video define or conceptualize what it means to be White?

- What insights does the video offer about the role of White individuals in challenging racism? How are these insights connected to broader social justice efforts?

- How does the video challenge viewers to reflect on their own experiences and identities in relation to Whiteness? What questions or prompts does it provide for personal reflection?

- What connections can you make between the video’s content and other discussions or materials on race and identity? How does this video contribute to or enhance your understanding of these topics?

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a framework developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw to understand how various social identities intersect and create unique experiences of oppression and privilege. When applied to racial identity, intersectionality explores how race interacts with other aspects of identity, such as gender, class, sexuality, and disability, to shape an individual’s experiences and social realities. Intersectionality acknowledges that individuals possess multiple overlapping identities that cannot always be separated (e.g., the experience of being a Black queer woman). One cannot examine race, gender, or sexuality alone; all dimensions of identity must be acknowledged in the individual’s experience. Thus, individuals may have both marginalized and privileged identities in various situations. Intersectionality has become a crucial concept in social justice movements because it emphasizes the necessity of acknowledging the intricate and overlapping nature of oppression. This approach promotes the creation of fairer policies and practices by examining how different forms of discrimination intersect and impact people in diverse ways (Carbado et al., 2013).

Racism in the United States

Racism is a system of beliefs, behaviors, and institutional structures that perpetuate unequal power relations based on racial or ethnic identity. It encompasses prejudice, discrimination, and antagonism directed against individuals or groups based on their race, rooted in the belief that some races are inherently superior or inferior to others (American Psychological Association [APA], 2023). Racism operates on multiple levels, including individual, institutional, and structural levels.

Prejudice and discrimination are both forms of racism. Prejudice involves making assumptions about individuals based on their association with a particular group, which can result in biased attitudes and behaviors. Discrimination is the act of treating individuals differently based on prejudice related to race, ethnicity, or other affiliations (APA, 2023). Discrimination comes in various forms, such as sexism, disability discrimination, ageism, classism, homophobia, and racism. Targeted groups may be defined by race, gender, ethnicity, or LGBTGEQIAP+ status.

Scientific racism misuses scientific methods to justify the belief in the inherent superiority or inferiority of different racial groups. Scientific racism typically involves the manipulation of anthropological, biological, and genetic data to create a pseudoscientific basis for racial discrimination. Examples of the impacts of scientific racism include social hierarchies, colonialism, slavery, and discriminatory policies. Despite being widely discredited by modern science (attribution here), the legacy of scientific racism continues to influence social attitudes and institutional practices today.

Video: Darwin, Africa, and Genocide: The Horror of Scientific Racism

Video: Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism

Discussion Questions

- What is scientific racism, and how has it historically been used to justify social hierarchies and discriminatory policies?

- In what ways did scientific racism influence public policy, education, and social norms in the 19th and 20th centuries? How do these influences persist in current societal structures or beliefs?

- How has scientific racism affected marginalized communities? What are the long-term impacts on these groups?

- How do the concepts of eugenics and biological determinism relate to scientific racism? In what ways have these concepts resurfaced in modern discussions about race, genetics, and intelligence?

The impacts of racism operate at multiple levels throughout society. Racism can be covert and systemic as well as overt and individualized. The former appears in institutional policies and practices, while the latter emerges in personal interactions and implicit biases. Individual racism occurs when someone treats another individual negatively based on their race or ethnic background (Meadows-Fernandez, 2019). Structural racism (sometimes referred to as systemic racism), on the other hand, refers to the existence of racism in systems that hold power. Examples include unequal treatment of racialized people in healthcare, education, employment, media, housing, and legislation. Systemic racism restricts oppressed groups from accessing resources that other groups can freely access (Meadows-Fernandez, 2019).

Video: Types of Racism

Video: What Is Systemic Racism in America?

Video: Structural Racism Explained

Discussion Questions

- How do individual racism and systemic racism interact to perpetuate racial inequality?

- What are some examples of structural racism? How do these structures reinforce racial disparities in areas like education, healthcare, housing, or employment?

- In what ways might the concept of colorblindness contribute to the perpetuation of structural and systemic racism?

- What role does individual racism play in maintaining or challenging structural and systemic racism?

- Why is it important to differentiate between individual, structural, and systemic racism when discussing racial inequality? How can understanding these different forms of racism lead to more effective strategies for social justice?

Anti-Black Racism in the United States

It is worth emphasizing that although race is a social construct, its construction has “created racial realities with real effects” (Burton et al., 2010, p. 444). These effects manifest in tangible ways across society, influencing how people are perceived and treated. While race has no biological basis, it has been historically used to stratify society and impact access to resources. Stratification based on race has led to oppressive systems and significant issues with racism in the United States and beyond.

The complexity of racial dynamics requires thoughtful examination across different contexts and communities. While acknowledging that there are many other stories and experiences in the United States around race, we have chosen to focus this chapter on people of African descent in the United States. We use the racial descriptors of African, African American, and Black somewhat interchangeably, but primarily chronologically. This approach reflects the evolving nature of racial identity and self-identification over time and acknowledges and respects “that Africans forced to come to this country did not racialize themselves as Black in their homelands; they had their own indigenous roots and tribal beliefs; they were connected to lands, customs, and cosmologies” (Mays, 2021, p. 4).

Slavery

The history of African-descended people in the Americas does not begin with enslavement. Still, to understand the full impact of racial construction in the United States, we must confront the foundational role that the institution of slavery played in establishing and reinforcing a race-based social hierarchy. Human slavery has existed for centuries across all regions of the world (Stevenson, 2018). To justify the Greek practice of slavery, Aristotle wrote, “Humanity is divided into two: the masters and the slaves, or if one prefers it, the Greeks and the Barbarians, those who have the right to command and those who are born to obey” (Kendi, 2016, p. 17). However, “American slavery, which lasted from 1619 to 1865, was not the slavery of ancient Greece” (Wilkerson, 2023, p. 44).

Unlike historical forms of bondage that sometimes allowed for eventual freedom or a measure of social mobility, slavery was uniquely cruel in the United States. Enslaved Africans were treated not as temporary servants but as permanent property to be bought, sold, and inherited across generations. Further, the institution of slavery established a rigid binary social system, where “slave” and “free” became the fundamental categories determining one’s rights and humanity (Berlin, 1998). Over time, this stratification became increasingly racialized, with “slave” becoming synonymous with African ancestry while “free” status was protected for and associated with Whiteness. This racial codification was formalized through laws like Virginia’s 1662 statute decreeing that a child’s status followed the mother’s condition, ensuring that children born to enslaved African women remained enslaved regardless of their father’s race or status, thereby cementing the economic and social equation of Blackness with bondage and Whiteness with freedom.

The United States would not have gained status as a global power as quickly as it did without its created system of slavery (Wilkerson, 2023). Baptist (2014) points out that “Enslaved African Americans built the modern United States, and indeed the entire modern world…”(p. xxv). This economic system required ideological justification, leading to the deliberate construction of “race” as a concept that positioned Africans as inherently inferior and thus suited for enslavement. Pseudo-scientific theories emerged to rationalize this hierarchy, with scholars, physicians, and religious leaders generating “evidence” of Black inferiority to defend the institution (Davis, 2006). These fabricated racial distinctions served to dehumanize enslaved people, making their brutal treatment appear natural and necessary within the American economic system.[1]

Colonization

Slavery was a significant part of everyday life during colonial times (Warren, 2016; Wilkerson, 2023). In the mid-1600s, England entered the African slave trade to provide labor for its island colonies. The first enslaved Africans arrived in North America’s English colonies in 1619. By the end of the 1600s, English slave traders “carried more than a quarter of a million men, women, and children across the ocean, shackled in ships’ holds” (Lepore, 2018, p. 47). Enslaved Africans were the source of free labor on plantations, mostly in the Southern states. This was because the Northern states did not cultivate large-scale agrarian crops like cotton or sugar. In the Northern Colonies, enslaved Africans were often used for domestic labor. Domestic labor, although valuable, did not have the same market value as slave labor that produced exportable crops (Warren, 2016). Therefore, “enslaved people never made up for more than 5 or 10 percent of the population…” in Northern Colonies (Warren, 2016, p. 133).

English colonists created laws to justify and protect their use of enslaved people, especially Africans, for labor. “With each new charter, with each new constitution, with each new slave code, England’s American colonists upended assumptions and rewrote laws governing the relationship between the rulers and the ruled” (Lepore, 2018, p. 52). English colonists established a caste system with “only two colors, black and white, and two statuses, slave and free” (Lepore, p. 70).

In 1638, the first rebellion of enslaved people occurred at an English colony on Providence Island (Warren, 2016). It was not the last. After a series of rebellions by enslaved people, including the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, colonists created increasingly dehumanizing laws to ensure complete control over enslaved people (Lepore, 2018). For example, South Carolina passed An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes, which “restricted the movement of slaves, set standards for their treatment, established punishments for their crimes,” and “made it a crime for anyone to teach a slave to write” (Lepore, p. 59). According to Kendi (2016):

No matter what African people did, they were barbaric beasts or brutalized like beasts. If they did not clamor for freedom, then their obedience showed they were naturally beasts of burden. If they nonviolently resisted enslavement, they were brutalized. If they killed for their freedom, they were barbaric murderers. (p. 70)

American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War was not fought for or against slavery, but slavery was still an issue. English colonists instigated the revolution for various reasons. Many of the colonists resented the control and oversight of the English government. However, as with many other wars, this one had much to do with greed (Lepore, 2018). Taxes imposed on the English colonists by the English crown, including the American Revenue Act and the Stamp Act, provoked anger among colonists. The colonists argued that “taxation without representation…is rule by force, and rule by force is slavery” (Lepore, p. 81). John Adams, who opposed the Stamp Act, wrote that “[we] won’t be their negroes” (Lepore, p. 82).

As author Jill Lepore (2018) stated: “It was lost on no one that the loudest calls for liberty in the early modern world came from a part of the world that was wholly dependent on slavery” (p. 64). In 1775, English colonist Samuel Johnson wrote in his Taxation Not Tyranny pamphlet, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?” (as cited in Lepore, 2018, p. 92).

Discussion Questions

- How do the quotes from Jill Lepore and Samuel Johnson illustrate the paradox of liberty and slavery in the early modern world?

- Reflect on the moral implications of advocating for liberty while simultaneously participating in or benefiting from the enslavement of others.

- How might these historical perspectives inform contemporary discussions about freedom, justice, and human rights?

Post-Revolutionary War

After the Revolutionary War, the concept of race became incredibly powerful across the colonies. Beliefs about race and White American supremacy were used to justify capitalist greed and slavery, and these beliefs influenced the governing principles of the developing United States (Baptist, 2014; Jones, 2023). Debts owed to domestic creditors and foreign allies as obligations from financing the war became a major political challenge in the early republic. The newly formed federal government was in an economic crisis, and the Articles of Confederation gave it no power to raise money. The new United States government had to decide how to tax individual states, particularly whether they should pay based on population or property. This question became more complicated by the fact that enslaved people were considered property. In addition, this issue reinforced the distinction between the Northern and Southern states around slavery. While the enslaved population had grown in the Southern states, it had decreased in the Northern states during the Revolutionary War (Lepore, 2018).

In 1787 at the Constitutional Convention, delegates from each state gathered to deliberate on what would become the Constitution of the United States. Four significant compromises, all related to slavery, were negotiated during the convention: the Northwest Ordinance, the Connecticut Compromise, the Three-Fifths Compromise, and the Compromise on the Importance of Slaves. The consequences of the four compromises proved devastating to the United States.

The first compromise was the Northwest Ordinance, which decreed that any new states established north of the Ohio River would be free states, and any new states established south of the Ohio River would be slave states (Lepore, 2018).

The second compromise was the Connecticut Compromise. The Connecticut Compromise ensured that each state would have an equal voice in the Senate, granting each state two senators. Meanwhile, in the House of Representatives, the number of representatives for each state would be determined by population, allowing for representation based on the demographic size of each state.

Related to the Connecticut Compromise, the third compromise, known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, established that enslaved people would be counted as three-fifths of a person. This addressed the issue of how individual states would be represented in the House of Representatives. The Three-Fifths Compromise gave slave states more representation in Congress, providing the Southern states with a political advantage. In addition, this compromise resulted in Southern states having greater representation in the Electoral College (Lepore, 2018).

The final compromise was between those who were against the slave trade and those who supported it. This clause in the United States Constitution prevented the new government from restricting the importation of people for 20 years. While it did not specify slavery, this compromise was aimed at continuing to allow slave importation while the newly formed government was established. The clause expired in 1808 (Lloyd & Martinez, n.d.). By 1816, the United States’ two political parties were almost equally divided between anti-slavery and pro-slavery (Lepore, 2018).

The Three-Fifths Compromise was the result of the disagreement between the Northern and Southern states over how slaves should be counted for representation and taxation in the United States. Southern states wanted slaves to be counted as part of their population to increase their representation in the House of Representatives. In contrast, Northern states objected, arguing that slaves should not be counted as they were considered property. As a compromise, it was agreed that three-fifths of the total slave population would be counted for both representation and taxation purposes. This compromise had significant implications for the distribution of political power in the forming United States.

Discussion Questions

- Analyze the causes and consequences of the Three-Fifths Compromise. How did this agreement reflect the political and economic tensions between the Northern and Southern states?

- What were the lasting implications of the Three-Fifths Compromise for the distribution of political power and the institution of slavery in the United States?

- What might the long-term consequences of the Three-Fifths Compromise be? How might this impact how we view race today?

Abolitionists

Many free Black people, some formerly enslaved, fought against the slavery of African and Black people. “It must be noted that long before white people established formal antislavery societies, Black people had been resisting their enslavement” (Herschthal, 2021, p. 11). Black people such as Harriet Tubman, David Walker, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth risked their freedom and lives to fight for social justice.

During the mid-1700s, a small minority of Quakers had begun to question the morality of slavery (Kendi, 2016; Lepore, 2018). Quakers such as John Woolman, Anthony Benezet, and Benjamin Lay believed that slavery contradicted Christian principles (Kendi, 2016). By 1775, Quakers had already banned slavery and excluded enslavers from their membership (Herschthal, 2021; Lepore, 2018).

Video: John Woolman – Friends in History

In the English colonies, Christianity was used to both justify and denounce slavery. When many others participated in slavery, both actively and passively, John Woolman chose a different path and was an active abolitionist.

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the dual role of Christianity in the context of slavery in the English colonies. How was religion used to both justify and oppose the institution of slavery?

- What do you think makes it possible for some, like John Woolman, to choose to advocate for social justice?

By the end of the 1700s, formal abolitionist and anti-slavery societies formed in the United States. Many of the earliest White members of anti-slavery societies supported a gradual approach to ending slavery. They advocated banning the transatlantic slave trade and enacting emancipation laws (Herschthal, 2021). However, even while some claimed to be against slavery, they continued to view Black people as naturally inferior to White people (Kendi, 2016; Warren, 2016). Others, such as Benjamin Rush, believed being enslaved was what made Black people inferior to White people (Kendi, 2016). Anti-slavery sentiments did not equate to racial egalitarianism beliefs.

By the 1820s, some White people who supported the end of slavery “came to believe that gradual emancipation would occur only if freed Black people were voluntarily resettled outside of the United States” (Herschthal, 2021, p. 13). The American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded in 1816 and was a mix of pro- and anti-slavery elite White men. It was initially formed to remove free Black people from the United States. The underlying belief was that Black people would never be accepted as equals in society and should be sent somewhere else to colonize their own country. In the early 1820s, delegates from the ACS traveled to West Africa and purchased land for colonization. A small number of emigrants were even sent to West Africa. However, the colonization failed due to objections from Black Americans, financial concerns, high mortality for the emigrants, and hostility from the Indigenous people of West Africa towards colonization (Robinson, 2022).

In the 1830s, abolitionist societies started becoming racially integrated and allowing female members: a significant change from earlier efforts led mainly by White men. This shift brought new perspectives and energy to the movement. Additionally, abolitionist movements began to demand an immediate end to slavery, moving away from earlier ideas of gradual abolition (Herschthal, 2021).

The West

As westward expansion progressed, the United States government grappled with the issue of slavery in new territories and states. Indiana (1816) entered the United States as a free state, whereas Louisiana (1812) and Mississippi (1816) entered as slave states. Slavery was expanding into the western part of the United States (Lepore, 2018).

In 1819, Missouri became the first territory acquired through the Louisiana Purchase to seek admission to the Union as a state. Missouri’s application for statehood raised critical questions about whether Missouri would enter the Union as a free or slave state, highlighting the growing tensions between the North and South. In 1820, after much political debate, Congress negotiated the Missouri Compromise. The Missouri Compromise was the Northwest Ordinance but with new boundary lines. The Missouri Compromise declared that any state north of a certain latitude would enter the Union as a free state, and any state south of that point would enter the Union as a slave state (Lepore, 2018).

The Compromise of 1850 was a series of legislative measures passed by the United States Congress aimed at resolving conflicts between the North and South over the issue of slavery. The Compromise of 1850 was intended to appease both Northern and Southern states. This compromise included California becoming a state, not restricting slavery in either of the territories of Utah or New Mexico, and creating a stronger law regarding fugitive slaves. In addition, the Compromise of 1850 abolished slavery in Washington, D.C. (Murray & Hsieh, 2016).

The strengthened Fugitive Slave Law outlined in the Compromise of 1850 “gave slavery a dark face throughout the North that had not existed before” (Murray & Hsieh, 2016, p. 22). Northerners became aware of and resentful of the federal resources being used to capture escaped enslaved people. For example, in 1854, President Franklin Pierce “sent the marines, cavalry, artillery, and a revenue cutter to hold and then ship a single escaped slave back to bondage” (Murray & Hsieh, p. 22). Many Northerners felt this was a waste of valuable government funds.

In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created two new territories, Kansas and Nebraska, west of Missouri. Under the 1820 Missouri Compromise, both territories should have joined the Union as free states. However, the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise and decreed that the new states’ free or slave status would be determined by the voters (Lepore, 2018). “The battle that followed the introduction and simultaneous denunciation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the most thunderous in the history of congressional debate over the expansion of slavery” (Baptist, 2014, p. 371).

The Kansas-Nebraska Act outraged Americans living in the Northern states and abolitionists (Lepore, 2018). This led to a period of violent conflict known as “bleeding Kansas” (Cowie, 2022, p. 106), as settlers on both sides of the slavery debate rushed into Kansas to impact the vote. Conflict erupted in the streets: “Bands of free-soil guerrillas, known as Jayhawkers, battled with militant bands of border ruffians interested in making Kansas a slave state by whatever means they could. The open clash between free and slave forces turned the territory into Bleeding Kansas” (Cowie, p. 106). The violence following the Kansas-Nebraska Act is known to have been a critical step toward the Civil War.

The Three-Fifths Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act further deepened the political disparity between Northern and Southern states. The Southern states exploited these agreements to bolster their political power by inflating their population through the increased numbers of enslaved people. This strategic manipulation allowed them to exert significant influence over the political landscape of the United States, tipping the balance in their favor (Lepore, 2018).

Justification for Secession

In the 1850s, Americans were still divided on the issue of slavery, and the United States was on the brink of a crisis. Even though Congress had banned discussions about slavery, it was a topic of debate across the country. Many Americans believed that the United States could not remain both anti-slavery and pro-slavery (Lepore, 2018). New York Senator William H. Seward stated, “It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slave-holding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation” (Lepore, p. 282).

King Cotton

In 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin (Hamalainen, 2019). By the mid-1800s, the Southern states produced approximately half of the world’s cotton; by 1820, Southern cotton was the most widely traded commodity in the world (Baptist, 2014). By 1936, “more than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States…derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million-odd slaves–6 percent of the total U.S. population” (Baptist, 2014, p. 322).

By the 1850s, cotton production in the Southern states had doubled, and after a short dip in the 1840s, the Southern economy was again booming (Baptist, 2014). More importantly, Southerners were not ready or willing to surrender their political power. They would soon prove their willingness to fight to retain it (Hamalainen, 2019; Lepore, 2018).

The Price of Humanity

In 1807, the United States Congress enacted the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves, which barred the importation of enslaved individuals to the United States. This legislative measure directly challenged the institution of slavery in the United States. Despite this challenge, the Act did not abolish slavery, nor did it forbid the procreation of enslaved individuals. Exploiting this loophole in the Act, slaveholders intensified the practice of coerced breeding. If an enslaved woman was unable to conceive with one man, she was compelled to bear children through forced unions with others (Faderman, 2022).

As early as 1662, the Colony of Virginia assembly created a law that “defined slavery by the status of the mother, reflected in the Latin phrase partus sequitur ventrem” (Berry & Gross, 2020, p. 33). The law decreed that any child born to a slave would be born into slavery. This meant that White male enslavers could profit from their own children born to enslaved Black people (Kendi, 2016). By 1663, the Province of Maryland passed the same law (Berry & Gross, 2020). When the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves passed, forced breeding became a way to continue the practice of slavery without importing new slaves.

Discussion Questions

- What were the economic and social implications of the law requiring children born to enslaved mothers to inherit their mother’s enslaved status?

- In what ways did the laws in Virginia and Maryland reflect the attitudes and practices regarding race and slavery in the 17th-century American colonies? How were these attitudes perpetuated into the 1800s when the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves was passed?

- What was the impact of the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves on the practice of slavery in the United States?

- Discuss the moral and ethical implications of forced breeding to continue slavery after the importation of slaves was banned.

By the 1830s, ownership of enslaved people was deeply intertwined with the United States economy, and slaves were considered an investment that could have significant returns for their owners. This was particularly true in the South, where the economy relied on slavery to cultivate cash crops. Southern banks accepted slaves as collateral on loans, and in 1859, enslavers in the state of Louisiana raised $25.7 million by mortgaging enslaved people (Baptist, 2014).

In the 1850s, there was a marked rise in opposition to slavery in the free states, while simultaneously, there was a surge in support for pro-slavery views in the slave states. This shift was influenced by the rising price of slaves, which soared from an average of $900 in 1850 to $1,600 a decade later. Due to the increasing purchase prices for enslaved people, some enslavers suggested re-establishing the transatlantic slave trade. Pro-slavery groups like the African Labor Supply Association (ALSA) justified this idea using the principle of free trade (Lepore, 2018). By 1860, “the United States had become the largest slaveholding nation in the world” (Herschthal, 2021, p. 12).

Slave Stampede

During the early to mid-1800s, many Americans were dissatisfied with the government’s attempt at compromise regarding slavery. Enslavers felt that free states threatened their way of life and feared there would be a “slave stampede” to the free states (Lepore, 2018, p. 280). On the other hand, many abolitionists and residents of free states believed that the compromises allowed the perpetuation and expansion of an immoral and inhumane institution, which they wanted to see abolished entirely.

On October 16, 1859, the fears of enslavers were realized when abolitionist John Brown and 21 other men launched a raid on the United States Armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Brown planned to incite a massive uprising among enslaved people, arming them with weapons seized from the armory. However, Brown’s mission was unsuccessful, as enslaved people were unaware of Brown’s intentions and did not join the insurrection (Herschthal, 2021). Colonel Robert E. Lee and the United States Marines quickly stopped Brown and his group. “Barely twelve hours after the raid had begun, headlines were being telegraphed across the continent: INSURRECTION…at Harper’s Ferry…GENERAL STAMPEDE OF SLAVES” (Lepore, 2018, p. 283). Brown was found guilty of conspiracy, murder, and treason, and was executed on December 2, 1859 (Lepore, 2018).

After Brown’s raid, Southern enslavers’ fears increased. Six days after Brown’s execution, Mississippi Congressperson Reuben Davis stated in a speech to Congress that the federal government had betrayed the South and, therefore, “to secure our rights and protect our honor we will dissever the ties that bind us together, even if it rushes us into a sea of blood” (Lepore, 2018, p. 285). In preparation for the 1860 presidential election, Southern states’ legislatures stockpiled arms and began plotting a coup (Baptist, 2014). The South was preparing for war.

Secession

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States on an anti-slavery platform (Baptist, 2014). As expected, Lincoln did not win any slave states (Lepore, 2018). Within six weeks of Lincoln’s election, South Carolina’s legislation voted to repeal their ratification of the United States Constitution. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and finally, Texas, followed South Carolina’s lead (Lepore, 2018). By February of 1861, the seven Southern states formed the Confederate States of America, with former Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis as president (Lepore, 2018).

Civil War (1861-1865)

At its core, the American Civil War was a conflict over slavery. With Lincoln elected president, the Confederacy identified the institution of slavery as the cornerstone of its decision to secede from the United States of America. In April of 1861, President Lincoln “raised the Union Army to put down the insurrection” (Kendi, 2016, p. 215).

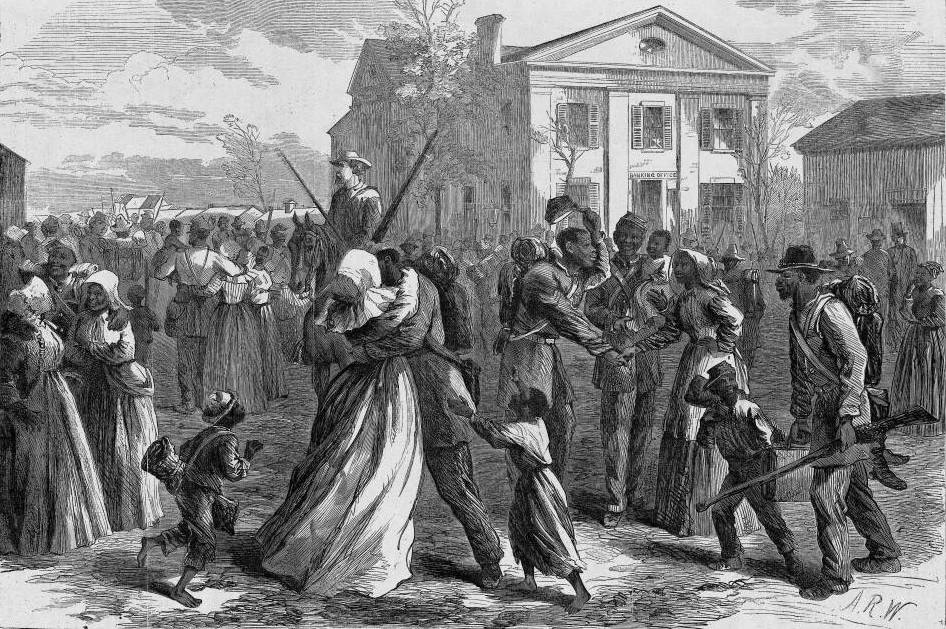

The original goal of the Union Army was to preserve the Union. However, in 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which intensified the debate over the institution of slavery. After four years of brutal battle, “some 750,000 soldiers plus an unknown number of civilians” died (McPherson, 2015, p. 2). The Union ultimately won the war in 1865, resulting in the abolition of slavery and laying the groundwork for the ongoing struggle for racial equality in the United States.

Video: Confederate Reckoning: Teaching the history of the Confederacy

Confederate apologists are individuals who defend the actions of the Confederacy during the Civil War by minimizing the issue of slavery and emphasizing other political factors, such as states’ rights and constitutional principles. Baptist (2014) states:

Ever since the end of the Civil War, Confederate apologists have put out the lie that the southern states seceded and southerners fought to defend an abstract constitutional principle of “states’ rights.” That falsehood attempts to sanitize the past. Every convention’s participants made it explicit they were seceding because they thought secession would protect the future of slavery. (p. 390)

Discussion Questions

- What are the main arguments put forth by Confederate apologists regarding the causes of the Civil War? How do these arguments compare with historical evidence?

- Why is it important that Confederate apologists attempt to downplay or minimize the role of slavery in the Civil War? How might this impact Black people in the United States today?

- What role do Confederate monuments, symbols, and memorials play in perpetuating or challenging the narratives promoted by Confederate apologists?

The Emancipation Proclamation

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation (Lepore, 2018). Lincoln used the preliminary Proclamation to issue an ultimatum to the Confederate States: “On the first day of January…all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free” (National Archives, n.d.). The Confederate states refused to comply.

As promised, Lincoln issued the official Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. As Lincoln signed the Proclamation, he said, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing the right thing than I do in signing this paper” (Lepore, 2018, p. 299). With his signature, Lincoln declared that all persons held as slaves within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free” (National Archives, n.d.).

The Proclamation granted Black Americans the right to serve in the Union Army, and it is estimated that over 200,000 chose to do so (Baptist, 2014). This was significant for Black Americans, as Frederick Douglass stated:

Let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters US…a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States. (as cited in Baptist, 2014, p. 401)

The Emancipation Proclamation was a noteworthy step toward freeing enslaved people in the seceded Confederate States. However, it was also a political tactic of war and did not declare the entire population of slaves in the United States to be freed. The Emancipation Proclamation only freed Southern slaves of the Confederacy and did not include those enslaved in Northern or Union states. It also did not apply to enslaved people in certain Southern states, like parts of Louisiana and West Virginia, that were pro-Union or working with the Union. Additionally, enslaved people in border states and Union-held territories such as Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were not granted freedom under the Proclamation. In total, about 3.9 million enslaved people remained in bondage after the Proclamation was issued (Baptist, 2014).

Reconstruction (1865-1877)

The Emancipation Proclamation laid the groundwork for Reconstruction, which began in 1865 and ended in 1877 with the recall of federal troops from the Southern states (Alexander, 2020). The end of the Civil War brought immense and immediate changes to the United States. Four million enslaved people were freed (White, 2017), federal income taxes were implemented, and “for the first time in U.S. history, voting directly impacted people’s pocketbooks” (Richardson, 2023, p. 27).

On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. On the same day, Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn into the office of the President of the United States. Most Americans believed that Johnson would follow in Lincoln’s footsteps regarding Reconstruction. However, during his presidency, Johnson’s only pro-Black Americans act was to support the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment (Levine, 2021). In the early months of his presidency, Johnson made it clear that he only planned for “restoration without a plan for reconstruction” (Levine, 2021, p. 55).

On May 29, 1865, Johnson enacted the Amnesty Proclamation, which declared “that he pardon most rebel leaders and just about all male citizens of the ex-Confederate states” (Levine, 2021, p. 54). During the second year of his presidency, Johnson refused to continue to fund the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was “a radical agency that challenged the racial hierarchies and exclusions that had been central to slave culture” (Levine, 2021, p. 106). Johnson also vetoed the Civil Rights Act, which would have granted citizenship to all native-born people except Indigenous people (Levine, 2021). Johnson claimed the Civil Rights Act favored Black people over White people.

Any progress in Black people’s rights was perceived by White Southerners as a threat to White people’s rights (Cowie, 2022), and President Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Act reinforced this belief (Levine, 2021). White Southerners saw themselves as victims of an oppressive federal government. They were determined “to restore the power dynamics of the master-slave hierarchy…using all tools at their disposal: political, religious, social, and economic” (Jones, 2023, p. 47). The only protection that Black Americans had from the systemic oppression of the South was federal protection (Levine, 2021). Many Black Americans believed that “federal power—especially the military—was the key source of leverage against the rebuilding of unrestrained white power” (Cowie, 2022, pp. 118-119). However, the farther away that protection was, the more danger Black Americans faced (Cowie, 2022). For example, federal troops were far away when, in 1865, Mississippi’s State Legislature passed what was known as the Black Codes. These were “racially based laws that effectively continued slavery by way of indentures, sharecropping, and other forms of service” (Lepore, 2018, p. 318). Black Mississippians “were prevented from carrying weapons, consuming alcohol, and from having any stand in a court of law” (Jones, 2023, p. 47). They were banned from congregating for religious worship, and Black ministers had to be licensed to preach (Jones, 2023). Mississippi’s Black Codes even went as far as controlling the lives of Black children. If a Black child was an orphan, they “could be forcibly apprenticed to any competent white person” (Jones, 2023, p. 48).

Other challenges during Reconstruction also affected the United States government’s ability to protect Black citizens. Soldiers wanted to return home after being deployed throughout the Civil War, and the financial burden of keeping the Union Army stationed in the South was substantial. Other regions of the country were also grappling with instability, and the resources of the United States government were wearing thin. Meanwhile, the United States was also engaged in conflicts with Indigenous tribes, leading to further deployment of federal troops to monitor borders in the West and Southwest. As a result, Black Americans in the Southern states were especially vulnerable (Lepore, 2018).

During the Reconstruction era, Black individuals and their White allies continued to advocate for Black rights. They recognized the need for collective action and formed organizations such as Union Leagues, Republican clubs, and Equal Rights Leagues. They called for recognition of their inherent dignity and humanity and fought for legal equality and access to the privileges and protections afforded to all citizens of the United States. Organizations addressed education, employment, housing, and public accommodations. Furthermore, these organizations advocated for suffrage rights. They mobilized voters, campaigned for voting rights legislation, and fought against voter suppression tactics aimed at disenfranchising Black voters (Lepore, 2018).

Reconstruction Amendments

Three amendments to the United States Constitution—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments—were ratified during the Reconstruction era.

The Thirteenth Amendment

On December 6, 1865, the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment changed the trajectory of the United States. The Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery by forbidding chattel slavery across the United States, except as punishment for a crime. When the Thirteenth Amendment was presented for a congressional vote, the Confederate States, having declared their independence and formed their own government, were not represented in the United States Congress. Despite this, the Thirteenth Amendment passed by only two votes (Cowie, 2022). Thus, “a third of those who remained in the union refused to vote for a constitutional amendment to end slavery” (Cowie, 2022, p. 123). Confederate States were later required to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment if they wanted to rejoin the Union (Cowie, 2022).

The Fourteenth Amendment

In 1868, Congress ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, although only one Southern state, Tennessee, voted for ratification. The Fourteenth Amendment declared that anyone born on United States soil, except Indigenous people, was automatically granted citizenship. The Fourteenth Amendment was designed to safeguard the rights of all citizens of the United States and restrain the authority of individual states by expanding the power of the federal government (Cowie, 2022).

The Fifteenth Amendment

In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, giving all men, except Indigenous men, the right to vote. This was one of the most critical issues during Reconstruction. However:

As everyone would learn and many knew…the Fifteenth was the weakest of the Reconstruction amendments. By banning a denial of the right to vote on the grounds of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, it left out the fact that a state could deny the right to vote for just about any other reason it selected (Cowie, 2022, p. 132).

Former slave and prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass believed that without Black men having the right to vote, “the war was not really over and not completely won” (Levine, 2021, p. 62).

Southern Backlash

While slavery officially ended in 1865, the racial categories it had established remained deeply embedded in the national consciousness of the United States. The ideology of White supremacy that had justified slavery transformed into new systems of oppression—such as Jim Crow segregation, sharecropping, convict leasing, and systematic disenfranchisement—all designed to maintain racial hierarchy without the legal institution of slavery itself. These systems were further reinforced through cultural representations, discriminatory policies, and both legal and extralegal violence against Black communities.

By 1873, White Southerners had employed various tactics and strategies to reclaim political, social, and economic dominance in the United States. At the beginning of the Reconstruction era, many White Southerners believed that they could continue to control free Black people “based on the old model of plantation paternalism” (Cowie, 2022, p. 141). When that failed, White Southerners engaged in any means necessary to regain power and subjugate Southern Blacks.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in December 1865. Initially a social club for Confederate veterans, it quickly turned into a clandestine group resisting Reconstruction efforts and terrorizing newly freed Black citizens. Operating mainly at night in white robes and hoods to hide their identities, Klan members carried out violent acts like lynchings and arson, targeting Black individuals and allies of civil rights. In response, Congress passed Enforcement Acts in 1870-71 to suppress Klan activities and protect Black rights. By the mid-1870s, Klan influence waned due to federal intervention, internal disputes, and the decline of Reconstruction policies. However, the KKK significantly influenced the American racial landscape, and its revival in 1915 has continued, even into modern times (Stewart, 2016).

Video: The KKK: Its History and Lasting Legacy

Discussion Questions

- What are the lasting impacts of the Klan’s actions during Reconstruction on race relations and civil rights in the United States?

- How have the tactics and ideologies of the KKK evolved over time? What challenges do they present to efforts to achieve racial equality?

- What strategies can be employed to counteract the influence of hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan and promote societal inclusivity and tolerance?

By the fall of 1873, brutal attacks on Black people by groups known as White Leagues or White Lines occurred in Southern states like Mississippi and Louisiana. White Line groups employed terror tactics, including murders, beatings, and intimidation, to suppress Black political participation. These groups were well organized and consisted of former Confederate soldiers, White Southern elites, and poor White citizens who saw the United States government as a threat to the Southern way of life. These White supremacists framed their violent actions as “redemption,” portraying themselves as saving the South from corruption and Black incapacity. This narrative was perpetuated for generations and continues to impact racial attitudes today (Cowie, 2022).

Reconstruction Failure

Many factors led to the ultimate failure of Reconstruction. One key issue was land redistribution, which was rejected, leaving Black people with no means of economic support. In addition, factionalism and corruption among Republicans undermined governmental reconstruction efforts. In the North, people were tired of war. Public sentiment had shifted, leaving people indifferent to the struggles of Black people in the South. The Northern interest in Southern politics also waned. In the South, there was an aggressive drive for redemption and to recreate the Southern systems that had existed pre-Civil War, including slavery. Widespread violence towards Black people erupted regularly (Cowie, 2022).

The United States government’s financial crisis depleted resources, leaving Black Southerners without federal protection (Cowie, 2022). By “the end of Reconstruction, a wave of terror had descended on the South… [and] the national government abandoned Blacks to state control” (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021, p. 14). As the federal government abandoned Black Southerners, White Southerners found new ways to abuse and terrorize Black Americans, such as convict leasing, sharecropping, and lynching (Cowie, 2022).

Convict Leasing

The Thirteenth Amendment legally abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” (Cowie, 2022, p. 196.) This clause, known as the exception clause, allowed White Southerners to create a system known as convict leasing. In this system, White labor contractors paid the fines of Black prisoners and bought out their prison sentences. Then, the White labor contractors presented Black prisoners with contracts, which they had no power to refuse, leasing them to mining operators, farmers, and plantation owners (Cowie, 2022).

Convict leasing was often more deadly than enslavement for Black convicts. Although technically Black convicts could gain their freedom, “their overseers had no investment in keeping them healthy or even alive,” as “convicts were disposable, cheap, and in near infinite supply” (Cowie, 2022, p. 192). Black convicts, kept in inhumane cells, were often beaten and whipped (Cowie, 2022). They were also charged for food, medical treatment, and other incidentals. “Under the lease system, the convicts could then work off their growing debt by adding additional time onto the sentence they received for their alleged crimes” (Cowie, 2022, p. 195).

The convict leasing system generated labor and a “substantial financial incentive to increase the number of local prisoners in the system” (Cowie, 2022, pp. 195-196). It was so profitable that it continued until World War II (Cowie, 2022). “Meantime, for well over half a century, convict labor afforded whites the freedom…to take out their unrestrained rage on their African American neighbors, for profit and politics alike” (Cowie, 2022, p. 209).

Sharecropping

After the Civil War, sharecropping emerged as a labor system in which formerly enslaved people worked land owned by others, typically White plantation owners. This system became widespread in the South during the Reconstruction era and persisted well into the 20th century. Under this arrangement, tenant farmers leased small plots of land and paid landowners a portion of their harvested crops. Although sharecropping initially appeared to offer a degree of independence, it effectively served as a mechanism to control Black labor, replicating many aspects of slavery (Foner, 2014).

The system of sharecropping subjected formerly enslaved individuals to exploitative economic practices, often trapping them in cycles of debt. These individuals received little legal protection, and the contracts they entered were frequently unfair and heavily biased in favor of White landowners. In addition, the legal system at the time overwhelmingly favored the interests of landowners. Sharecropping functioned to keep Black families economically dependent and socially subordinate. It sustained the racial hierarchy in the post-Civil War South and continued to perpetuate a system of racial and economic inequality (Foner, 2014).

Lynching

White Southerners believed that they had the right to kill Black Americans without cause or consequence (Cowie, 2022). Often, this was done through lynching. By definition, lynching is “to put to death (as by hanging) by mob action without legal approval or permission” (Merriam-Webster, 2025). Lynching is a practice that is in direct conflict with the United States judicial system and has roots in the institution of slavery.

The lynching of Black Americans, both men and women, was justified under many pretenses. One of the most common justifications was the “myth of having to protect white womanhood against Black bestiality” (Cowie, 2022, p. 236). Black men accused of sexually assaulting White women were burned, castrated, dismembered, and hung by White mobs. Ida B. Wells, a former enslaved Black woman, wrote, “White men used their ownership of the body of the white female as a terrain on which to lynch the black male” (as cited in Cowie, 2022, p. 236).

A journalist and anti-lynching activist, Wells launched an investigation into the practice of lynching in the South after three of her friends were lynched in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1892, she published her findings about lynching in the pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (Lepore, 2018). A few years later, in 1895, Wells published The Red Record, which was the first statistical report on lynching in the United States. Wells’ publications made her a national expert on the practice of lynching. In 1898, when Wells met with President McKinley, she gave him a petition, where she wrote:

For nearly twenty years lynching crimes…have been committed and permitted by this Christian nation. Nowhere in the civilized world save the U.S. of America do men, possessing all civil and political power, go out in bands of 50 and 5,000 to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual, unarmed and absolutely powerless. Statistics show that nearly 10,000 American citizens have been lynched in the past 20 years. (as cited in Mobley, 2021, para. 7)

However, President McKinley did not support a federal anti-lynching law. In 1900, when Congressman George White presented a federal anti-lynching bill to Congress, it did not pass, nor did the “nearly two hundred attempts to pass anti-lynching legislation” that followed (as cited in Mobley, para. 8).

During the early 1900s, some estimated that a Black American “in the South was hanged or burned alive every four days” (Lepore, 2018, p. 369). Lynching had become so normalized that incidents were written in newspapers like sporting events (Cowie, 2022). The terrorism of lynching Black Americans continued well into the mid-20th century.

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi for allegedly committing the crime of flirting with a White woman. When one of Emmett Till’s murderers was brought to trial, the White jury found him not guilty after 30 minutes of deliberation. Emmett Till and his family never received justice. It took the United States government 67 years after Emmett Till was murdered to pass federal anti-lynching legislation.

According to Kendi (2016), between 1979 and 1982, 28 young Black Americans were lynched in Atlanta. In 1980 alone, 12 Black Americans were lynched in the state of Mississippi.

On March 29, 2022, President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, which made lynching a federal hate crime. The Emmett Till Antilynching Act was the result of over 200 efforts by lawmakers to make lynching a federal crime.

Discussion Questions

- How did the murder of Emmett Till influence the Civil Rights Movement in the United States?

- How does the Emmett Till Antilynching Act of 2022 address historical injustices?

- Compare the public and legal responses to Emmett Till’s lynching in 1955 with the responses to racially motivated violence in recent years. What has changed, and what has remained the same?

- How does the signing of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act by President Joe Biden signify progress in addressing hate crimes in the United States?

Jim Crow Laws

Jim Crow laws, enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, institutionalized racial segregation and discrimination across the American South. These laws, named after a derogatory minstrel character, mandated the separation of Black people from White people in public spaces, including schools, transportation, and housing. The Jim Crow era was characterized by a systematic effort to enforce racial hierarchy and disenfranchise Black citizens through legal means. This legislative framework not only perpetuated racial inequality but also entrenched social and economic disadvantages for Black citizens, creating a pervasive environment of inequality in the United States. Understanding the origins, impacts, and resistance to Jim Crow laws is crucial for comprehending the broader struggle for civil rights and social justice in the United States history.

The Great Migration

In the 1900s, life had become increasingly difficult and dangerous for Black Southerners. The oppressive conditions and constant threats of violence, including lynching and discriminatory practices, created an unbearable and hostile environment. In response, many Black Americans embarked on a mass exodus known as the Great Migration. This movement, which started in the early 1900s and continued until the late 1960s, saw millions of Black Americans leave the South in search of greater opportunities and safer living conditions in the North and West. Before it began, only 10% of Black Americans lived outside of the South. By the end of the Great Migration, 37% of Black Americans had left the South (Wilkerson, 2023).

There were two waves of the Great Migration. The first wave started in 1910. “Between 1910 and 1920, 300,000 left; over the next ten years, 1.3 million; in the 1930s, 1.5 million left; and in the 1940s, 2.5 million” (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021, p. 16). The second wave of the Great Migration occurred between 1940 and 1945 (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021). Both waves were influenced by war and industrialization; however, at its core, the Great Migration was about the safety of millions of Black people. The Great Migration was a pivotal moment in American history, reflecting a profound quest for freedom and equality amidst the harsh realities of Jim Crow-era America (Wilkerson, 2023).

Video: The Great Migration: Crash Course in Black American History #24

Video: The Great Migration and the Power of a Single Decision

Discussion Questions

- What were the primary factors that made life increasingly difficult and dangerous for Black Southerners in the early 1900s?

- What were some of the significant social, economic, and cultural impacts of the Great Migration on the regions Black Americans moved from?

- What were some of the significant social, economic, and cultural impacts of the Great Migration on the regions Black Americans moved to?

- How does the Great Migration continue to influence contemporary issues of race, migration, and urban development in the United States?

Collective Activism and Social Change

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

In 1908 in Springfield, Illinois, a mob of over 5,000 White citizens violently attacked Black neighborhoods in attempts to seek out and lynch two Black men, one accused of murder and the other rape. At least 17 people died, Black property and businesses were targeted and destroyed, and the state militia was called in. In the aftermath of few legal repercussions and fleeing Black citizens, it was clear that action and organization were necessary. In 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded by White journalists and social reformers in response to the Springfield Riot. The organization was established to advance civil rights and combat racial discrimination through legal challenges and advocacy. Over time, it became a leading force in the fight for racial justice, playing a crucial role in pivotal civil rights milestones and shaping national policy (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021; Richardson, 2023). Initially, W. E. B. Du Bois was the only Black officer in the organization, but his presence drew more Black leaders and activists to the NAACP. By 1919, the NAACP had grown to include approximately 100,000 members. By the 1920s and 1930s, the organization had a diverse leadership and membership, reflecting broad engagement from the Black community (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021).

The NAACP forced attention on what was happening to Black Americans that would otherwise have gone unnoticed by the majority of White Americans. “The NAACP had long focused on challenging racial inequality by calling popular attention to racial atrocities and demanding that officials enforce laws already on the books” (Richardson, 2023, pp. 14-15). In 1940, attorney Thurgood Marshall founded the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (Richardson, 2023). During the 1940s, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund sponsored many lawsuits that rose through the legal system to the United States Supreme Court. Some of those lawsuits, Smith v. Allwright (1944), Morgan v. Virginia (1946), and Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), were wins for Black Americans (Horowitz & Theoharis, 2021). These victories advanced civil rights and laid the groundwork for the landmark cases of the 1950s and 1960s, further dismantling legalized segregation and discrimination in the United States.

Video: The Springfield Race Riots

Discussion Questions

- What were the underlying social, economic, and political factors that contributed to the Springfield Race Riot?

- How did the riot impact the perception of racial violence in Northern states compared to the South?

- In what ways did the riot contribute to the formation of the NAACP, and what were the organization’s initial goals?

- What do you think of the actions in current-day Springfield, Illinois, to acknowledge the Springfield Race Riots? Is it enough? Why or why not?

World War II

The poet Langston Hughes wrote in his poem, Beaumont to Detroit: 1943:

You tell me that hitler

Is a mighty bad man.

I guess he took lessons

From the ku klux klan

(As cited in Nordell, 2021, p. 21)