Anticipation

Models of Organized End-of-Life Care: Palliative Care vs. Hospice

You matter because you are you, and you matter to the end of your life.

-Dame Cicely Saunders, Founder of the Hospice Movement

Learning Objectives

- Define palliative care and hospice care.

- Compare the similarities and differences between hospice and palliative care.

- Identify the advantages and disadvantages between hospice and palliative care.

As mentioned in the first chapter of this book, end-of-life care is a broad term used to describe specialized care provided to a person who is nearing or at the end of life. The following terms have been used in both clinical and research domains that fall within end-of-life care: palliative care, supportive care, comfort care and hospice care. For the purposes of this chapter, we will focus on the two most widely recognized and used among these terms: palliative care and hospice care. These two models of end-of-life care are not the same, though they are commonly misconstrued as such among the lay population as well as within the health care community. While both types of care operate under the same philosophical idea, each functions differently within the health care system. One of the main goals of this chapter is to help the reader understand the similarities and differences between hospice and palliative care. Nurses who care for patients nearing the end of life are in an ideal position to educate patients, families and other clinicians about these two formal end-of-life care programs.

Palliative Care

The term palliate is defined as “to reduce the violence of (a disease); to ease (symptoms) without curing the underlying disease” (Merriam-Webster, 2014). Palliative care is a broad philosophy of care defined by the World Health Organization as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients with life-limiting illnesses and their families through the prevention and relief of physical, psychosocial and spiritual suffering (World Health Organization, 2014). Palliative care, by definition, is the underlying philosophy for providing all aspects of comfort to a person living with a serious illness. Although palliative care is the underlying philosophy of most organized EOL programs such as hospice, it has become a healthcare specialty and care delivery system over the past decade. In the U.S. today, over half (55%) of all 100-plus bed hospitals have a palliative care program, and in hospital palliative care programs have increased by 138% since 2000 (Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2011).

Palliative care uses a team-based approach to evaluate and manage the various effects of any illness that causes distress. Patients who live with serious illnesses often have pain and other symptoms which require attention in order to improve the person’s quality of life and reduce any undue suffering. Patients with serious illnesses may also need emotional support to help them deal with the various decisions related to management of their disease. Palliative care clinicians can assist patients and families with these important care needs. Palliative care can be used with patients of any age and with any stage of illness with the overarching goal of improving the patient’s quality of life (Center to Advance Palliative Care, 2011). Thus there is no predetermined life expectancy required to be eligible for palliative care.

As mentioned previously, palliative care programs have increased steadily over the past decade in U.S. hospitals. Usually comprised of physicians, mid-level providers, and nurses, palliative care consultation teams obtain referrals to evaluate hospitalized patients who have some type of need, such as symptom management, or assistance with decision making in light of a serious diagnosis. Additionally, some larger hospitals can offer palliative care consultation services to outpatients for similar services as well. In addition to hospital-based palliative care programs, palliative care services can also be found in most home health care agencies. Sometimes palliative care is associated with the home care agency’s hospice program, often employing nurses who are specialized in both. In home health care, patients with serious illnesses often get admitted to the palliative care team and as their illness progresses, may eventually transition to home hospice care. If part of the same program, patients will be able to have continuity in care and consistency with the same nurse, who can care for them from admission through discharge.

Several sub-specialties of palliative care have been developed over the past few years, including pediatric and geriatric palliative care, which provide the same focus on improving quality of life in specialized populations, such as with children and the elderly. Palliative care is considered to be a specialty medical care but the way it is reimbursed differs from hospice reimbursement, which we will discuss more in the next section. Palliative care services are often paid for through fee-for-service, philanthropy, or by direct hospital support (ELNEC, 2010).

Hospice Care

The term “hospice” originated from medieval times when it was considered to be a place where fatigued travelers could rest (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2014). Hospice is both a type of organized health care delivery system and a philosophical movement (Jennings, Ryndes, D’Onofrio, Baily, 2003; Herbst, 2004). Currently, hospice is one type of end-of-life care program supported by Medicare reimbursement that is geared toward providing comfort for those who are at or near the end of life. Hospice incorporates a palliative philosophy of care and is used by people with serious illnesses who are nearing the end of life.

According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), the focus of hospice is on caring for instead of curing a person’s terminal illness. With origins from the United Kingdom, the first U.S. hospice opened in 1971, and hospice programs have grown rapidly. By 2012, there were 5,500 hospice programs in the U.S. (NHPCO, 2013). In 2012, 57% of patients received hospice in a free-standing hospice, 20% in a hospital, 17% from a home health agency, and 5% from a nursing home (NHPCO, 2013).

Although a cancer diagnosis was the most predominant diagnosis among hospice patients since hospice originated, the rate of hospice use among non-cancer diagnoses has significantly increased. In 2012, cancer diagnoses accounted for 36.9% of hospice admissions, whereas the remaining 63.1% were attributed to non-cancer diagnoses. Debility, dementia and heart disease were the top three of the non-cancer diagnoses among patients admitted to hospice care (NHPCO, 2013). Unlike palliative care, hospice is usually reserved for people who have a prognosis of 6 months or less, and a formal certification by a physician is required to be eligible for hospice care. The average length of stay for a patient from admission to discharge on hospice care is approximately 18 days,or roughly 3 weeks (NHPCO, 2013). Patients who are eligible for and who elect to receive hospice care can receive many services that are focused on promoting comfort and improving their quality of life. As with palliative care, hospice also uses a team approach and usually consists of a physician, nurse, and social workeras the main clinicians that are involved in their care. Additionally, they are eligible to receive other services as needed and requested by the admitting nurse. The following is a list of the usual covered services available to patients who elect the Medicare hospice benefit:

- Physician services (patients can elect one primary physician as their hospice provider)

- Nursing care

- Medical equipment and supplies related to the terminal illness

- Medications for management of pain, symptoms, and comfort

- Hospice aide services

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Social work services

- Dietary counseling

- Spiritual counseling

- Bereavement care

-Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2013

In addition to this certification, patients who elect hospice care usually have to be in agreement with forgoing all further curative life-sustaining medical treatments and only electing to receive palliative care interventions that improve their quality of life. The following are some of the curative type treatments that are NOT allowed once a patient is enrolled in hospice care:

- Inpatient hospitalizations for life-sustaining treatments

- Diagnostic interventions (x-rays, labwork, CT scans)

- Emergency room visits

- Specialist provider visits

- Outpatient services

- Ambulance services

-Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2013

When patients elect hospice care, payments for all of their care come from the designated money allocated to hospice from their medical insurance provider. The majority of patients who elect hospice are on Medicare, and Medicare has a special hospice benefit that covers hospice care for beneficiaries from a Medicare-certified hospice program. In 2012, 83.7% of all hospice claims were covered by Medicare, 7.6% by managed care or private insurance, and 5.5% by Medicaid (NHPCO, 2013).

Similarities and Differences between Hospice and Palliative Care

Both hospice and palliative care provide specialized care and support for individuals living with serious illnesses using an interdisciplinary team approach. The main goal with both is to improve the quality of life for patients through interventions that focus on improving comfort and reducing the complications associated with their illness. Both programs are family-oriented, meaning that the care that is provided is intended to support both the patient who is living with the disease and the family who is caring for them.

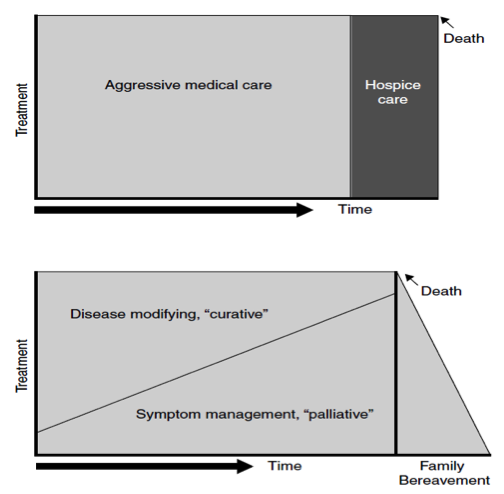

Although palliative care is ideally implemented alongside curative care when a person is diagnosed with a serious illness, hospice care is reserved for persons who have a life expectancy of less than 6 months as certified by their physician and for whom curative medical treatments are no longer an option or are desired by the patient. Figure 4.1 depicts two models of care: the first is the model that most commonly occurs in which there is a shift in the focus of care from curative to palliative very close to death. The second figure depicts the more ideal model in which palliative care is initiated right at the time of initial diagnosis. Historically, the first model is what is usually followed, whereas there is a distinct time when the focus switches from aggressive medical care to comfort care provided by hospice.

Hospice care requires a prognosis of 6 months or less, whereas palliative care does not have a prognosis requirement. Hospice requires patients to forgo all medical treatments that are considered to be life-sustaining or curative and the focus of care completely shifts to comfort-oriented care. With palliative care, patients can receive life-sustaining or curative treatments right alongside palliative care. Looking at the first image in Figure 4.1, you will see that there is a distinct vertical line separating aggressive medical treatments and hospice care along the illness trajectory. This shows that there is a distinct separation between curative and comfort care, which was how hospice originally was created. Historically, hospice care was developed for and used by people whose illness trajectory depicted a rapid decline towards the end of life, such as in cancer. In cancer patients, there is usually a time when the physician can determine that the cancer is worsening and the curative treatments are no longer effective. This is often the time that the burdens of the treatment outweigh the benefits. For example, despite aggressive chemotherapy, the patient’s cancer continues to spread and is causing many adverse side effects. Often, patient’s lab values fall into an unacceptable range in which chemotherapy is contraindicated. With these examples, it becomes clear to the physician that the patient is worsening despite treatment, and that it is likely the right time to switch to comfort care. It is at this time that conversations about prognosis and goals for care are initiated and the patient and family begin to make some difficult decisions.

The variability in the differing illness trajectories of people with non-cancer illnesses often makes the transition to elect hospice care difficult. Although there are more patients with non-cancer illnesses who are electing hospice than ever before, many patients continue to enroll in hospice late, or not at all. There has been an abundance of research on this area as to why these patients are not getting hospice care and the reasons include patient, provider and systems-related barriers to enrollment in hospice care. Referring back to the first image in Figure 4.1, that distinct line which separates aggressive medical care from comfort/hospice care is more difficult to evaluate among patients with a non-cancer illness. There is often not a time when the physician can say with confidence that the patient has a prognosis of 6 months or less of life. This can be due to the fact that most curative-type treatments may not lose their effectiveness or become a burden that outweighs the benefit in patients with non-cancer illnesses. In fact for certain types of diagnoses, such as heart failure, the curative type treatments actually provide symptom management. Patients with heart failure commonly have exacerbations in which they require hospitalization and administration of medications that are considered by hospice as being curative and therefore would have to forgo if electing to make the switch to hospice care. So while hospice is a wonderful care program for patients who are close to the end of life, it might not be able to provide the types of services that certain diagnoses, such as heart failure, have been using for symptom management to improve the quality of life.

If you refer to the second image in Figure 4.1, you will find the ideal way palliative care was meant to be used throughout the illness trajectory. Right from the time of diagnosis, palliative care is also instituted. Although the level of palliative care may be small from the outset, it can increase throughout the trajectory of the individual as the aggressive curative treatments are decreasing. So as a patient’s health worsens and their illness becomes more advanced, the level of palliative care will increase. As death approaches, curative care will decrease and palliative care will increase. The difference with the second image is that no distinct switch to palliative care is required because palliative care has been part of the overall plan of care from the time of initial diagnosis. This has been shown to be the most effective way to manage symptoms and care needs, rather than having a distinct separation in between cure and comfort.

The problem in end-of-life care is that all too often, the first image is what happens, and many patients with those non-cancer diagnoses are not receiving effective management for the symptoms and problems that go along with their illness. In order to improve the end of life experience for patients, it would be better to manage those symptoms and problems from the outset so that patients can be as comfortable as possible, educated about what they might expect, and have been given the opportunity to talk with a clinician about their goals for care before their illness becomes too advanced.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Hospice and Palliative Care

As mentioned before, there is no universal reimbursement mechanism for palliative care, as there is with hospice. This may impede the ability for a patient to get palliative care from the time of initial diagnosis. Second, not all health care systems have a palliative care team or service, particularly the smaller and more rural hospitals. If palliative care is not available or not covered, patients will not be able to access it. This is partly why the first image in Figure 4.1 is what tends to happen in the illness trajectory. If electing hospice care means stopping all curative treatments, then patients and families will not opt for that until they are told that there is nothing else medically that can be done for them. Palliative care may be the best option for the patient at this time. Palliative care may be the better option initially for patients who have a serious illness which is still responding to medical treatments.

An advantage of electing hospice care is that patients who have minimal chance of prolonging their length of life due to their poor prognosis still have an option for care that will focus on their quality of life. Often people who have a life-threatening illness are told by their providers that there is nothing else medically that can be done to cure their illness. These words often make the patient feel as though they are stuck with dealing with their illness alone. They wonder what will happen to them if nothing more medically can be done This can be a frightening thought, and one of advantages of hospice is that patients do not have to feel alone. Hospice can provide that support 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and often just knowing that the nurse is just a phone call away can give significant peace of mind to patients and their families. Another advantage of hospice care are the various services that hospice can provide to patients. In home health care, hospice patients can have the most hours of home health aide services, which may be essential at the end of life in order to help alleviate some of the burden of care from the family. The hospice benefit also pays for all medications and medical equipment needed to maintain and maximize patient comfort. This includes home oxygen which for patients who are not on a hospice program and have to meet a specific criteria for oxygenation status in order to be eligible. On hospice, patients have an entire team of clinicians who work together to plan and provide an individualized plan of care. Using an interdisciplinary approach enables patients to receive a holistic, high quality plan of care. Determining which one of these two formal end of life programs patients should use requires understanding the patient’s individual goals and preferences for care. Once the clinician is aware of what the patient hopes in terms of their illness, then they can best advocate for their patient.

Although hospice and palliative care are the most frequently used services among patients who are at the end of life, it is possible to not use either one. Students often ask whether it is possible for patients to have what is considered a “good death” without being involved in a formal program such as hospice. Hospice and palliative care can assist patients and families to meet the various needs they will encounter during their final months of life, but are not mandatory. It is possible for patients to still have their goals and preferences for care met without hospice or palliative care involvement. However, patients would have to be well equipped with the knowledge of what they hope to accomplish and have healthcare professionals who are willing to listen to them and provide them that care. Patients who elect to not use either service should utilize a clinician with specialized knowledge in the areas that commonly require attention at the end of life, such as symptom management and psychosocial support.

What You Should Know

- Hospice and palliative care are often misunderstood to be the same thing, but they are not.

- Both hospice and palliative care provide specialized care services aimed to improve overall quality of life for patients with serious illnesses.

- Although palliative care is ideally instituted alongside curative care when a person is diagnosed with a serious illness, hospice care is reserved for persons for whom curative medical treatments are no longer an option.

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2013). Medicare hospice benefits. Retrieved from http://www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf

Center to Advance Palliative Care. (2011). Building a palliative care program. Retrieved from http://www.capc.org/building-a-hospital-based-palliative-care-program/

End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (2010). ELNEC – core curriculum training program. City of Hope and American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC

Herbst, L. (2004). Hospice care at the end of life. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 20, 753-765.

Jennings, B., Ryndes, T., D’Onofrio, C., & Baily, M. A. (2003). Access to hospice care: Expanding boundaries, overcoming barriers. Hastings Center Report, 33, (2), S3-S7.

Lynn, J. & Adamson, D.M. (2003). Living well at the end of life: Adapting health care to serious chronic illnesses in old age. RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/white_papers/WP137.html

Palliate [Def. 1]. (n.d.). Merriam-Webster Online. In Merriam-Webster. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/citation

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2014). Hospice and palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.nhpco.org/about/hospice-care

World Health Organization. (2014). WHO definition of palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/