Chapter 9: Conflict in Relationships

Conflict is a normal and natural part of life. However, learning how to manage conflict in our interpersonal relationships is very important for long-term success in those relationships. This chapter is going to look at how conflict functions and provide several strategies for managing interpersonal conflict.

9.1 Understanding Conflict

Learning Objectives

For our purposes, it is necessary to differentiate a conflict from a disagreement.1 A disagreement is a difference of opinion and often occurs during an argument, or a verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects. It’s important to realize that arguments are not conflicts, but if they become verbally aggressive, they can quickly turn into conflicts. One factor that ultimately can help determine if an argument will escalate into a conflict is an individual’s tolerance for disagreement. James McCroskey, along with his colleagues, initially defined tolerance for disagreement as whether an individual can openly discuss differing opinions without feeling personally attacked or confronted.2,3 People that have a high tolerance for disagreement can easily discuss opinions with pretty much anyone and realize that arguing is perfectly normal and, for some, even entertaining. People that have a low tolerance for disagreement feel personally attacked any time someone is perceived as devaluing their opinion. From an interpersonal perspective, understanding someone’s tolerance for disagreement can help in deciding if arguments will be perceived as the other as attacks that could lead to verbally aggressive conflicts. However, not all conflict is necessarily verbally aggressive nor destructive.

The term “conflict” is actually very difficult to pin down. We could have an entire chapter where we just examined various definitions of the term. Simplistically, conflict is an interactive process occurring when conscious beings (individuals or groups) have opposing or incompatible actions, beliefs, goals, ideas, motives, needs, objectives, obligations resources and/or values. First, conflict is interactive and inherently communicative. Second, two or more people or even groups of people who can think must be involved. Lastly, there are a whole range of different areas where people can have opposing or incompatible opinions. For this generic definition, we provided a laundry list of different types of incompatibility that can exist between two or more individuals or groups. Is this list completely exhaustive? No. But we provided this list as a way of thinking about the more common types of issues that are raised when people engage in conflict. From this perspective, everything from a minor disagreement to a knock-down, drag-out fight would classify as a conflict.

The rest of this section is going to explore the nature of conflict and its importance in communication. To do this, we’ll discuss two different perspectives on conflict (disruption vs. normalcy). Then we’ll explore interpersonal conflict more closely. Lastly, we’ll discuss the positive and negative functions of conflict.

Two Perspectives on Conflict

As with most areas of interpersonal communication, no single perspective exists in the field related to interpersonal conflict. There are generally two very different perspectives that one can take. Herbert W. Simmons was one of the first to realize that there were two very different perspectives on conflict.4 On the one hand, you had scholars who see conflict as a disruption in a normal working system, which should be avoided. On the other hand, some scholars view conflict as a normal part of human relationships. Let’s look at each of these in this section.

Disruptions in Normal Workings of a System

The first major perspective of conflict was proposed by James C. McCroskey and Lawrence R. Wheeless.5 McCroskey and Wheeless described conflict as a negative phenomenon in interpersonal relationships:

Conflict between people can be viewed as the opposite or antithesis of affinity. In this sense, interpersonal conflict is the breaking down of attraction and the development of repulsion, the dissolution of perceived homophily (similarity) and the increased perception of incompatible differences, the loss of perceptions of credibility and the development of disrespect. 6

From this perspective, conflict is something inherently destructive. McCroskey and Virginia P. Richmond went further and argued that conflict is characterized by antagonism, distrust, hostility, and suspicion.7

This more negative view of conflict differentiates itself from a separate term, disagreement, which is simply a difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people. Richmond and McCroskey note that there are two types of disagreements: substantive and procedural.8 A substantive disagreement is a disagreement that people have about a specific topic or issue. Basically, if you and your best friend want to go eat at two different restaurants for dinner, then you’re engaging in a substantive disagreement. On the other hand, procedural disagreements are “concerned with procedure, how a decision should be reached or how a policy should be implemented.”9 So, if your disagreement about restaurant choice switches to a disagreement on how to make a choice (flipping a coin vs. rock-paper-scissors), then you’ve switched into a procedural disagreement.

A conflict then is a disagreement plus negative affect, or when you disagree with someone else and you don’t like the other person. It’s the combination of a disagreement and dislike that causes a mere disagreement to turn into a conflict. Ultimately, conflict is a product of how one communicates this dislike of another person during the disagreement. People in some relationships end up saying very nasty things to one another during a disagreement because their affinity for the other person has diminished. When conflict is allowed to continue and escalate, it “can be likened to an ugly, putrid, decaying, pus-filled sore.”10

From this perspective, conflicts are ultimately only manageable; whereas, disagreements can be solved. Although a disagreement is the cornerstone of all conflicts, most disagreements don’t turn into conflicts because there is an affinity between the two people engaged in the disagreement.

Normal Part of Human Communication

The second perspective of the concept of conflict is very different from the first one. As described by Dudley D. Cahn and Ruth Anna Abigail, conflict is a normal, inevitable part of life.11 Cahn and Abigail argue that conflict is one of the foundational building blocks of interpersonal relationships. One can even ask if it’s possible to grow in a relationship without conflict. Managing and overcoming conflict makes a relationship stronger and healthier. Ideally, when interpersonal couples engage in conflict management (or conflict resolution), they will reach a solution that is mutually beneficial for both parties. In this manner, conflict can help people seek better, healthier outcomes within their interactions.

Ultimately, conflict is neither good nor bad, but it’s a tool that can be used for constructive or destructive purposes. Conflict can be very beneficial and healthy for a relationship. Let’s look at how conflict is beneficial for individuals and relationships:

- Conflict helps people find common ground.

- Conflict helps people learn how to manage conflict more effectively for the future.

- Conflict provides the opportunity to learn about the other person(s).

- Conflict can lead to creative solutions to problems.

- Confronting conflict allows people to engage in an open and honest discussion, which can build relationship trust.

- Conflict encourages people to grow both as humans and in their communication skills.

- Conflict can help people become more assertive and less aggressive.

- Conflict can strengthen individuals’ ability to manage their emotions.

- Conflict lets individuals set limits in relationships.

- Conflict lets us practice our communication skills.

When one approaches conflict from this vantage point, conflict can be seen as an amazing resource in interpersonal relationships. However, both parties must agree to engage in prosocial conflict management strategies for this to work effectively (more on that later in this chapter).

Now that we’ve examined the basic idea of conflict, let’s switch gears and examine conflict in a more interpersonal manner.

Interpersonal Conflict

According to Cahn and Abigail, interpersonal conflict requires four factors to be present:

- the conflict parties are interdependent,

- they have the perception that they seek incompatible goals or outcomes or they favor incompatible means to the same ends,

- the perceived incompatibility has the potential to adversely affect the relationship leaving emotional residues if not addressed, and

- there is a sense of urgency about the need to resolve the difference. 12

Let’s look at each of these parts of interpersonal conflict separately.

People are Interdependent

According to Cahn and Abigail, “interdependence occurs when those involved in a relationship characterize it as continuous and important, making it worth the effort to maintain.”13 From this perspective, interpersonal conflict occurs when we are in some kind of relationship with another person. For example, it could be a relationship with a parent/guardian, a child, a coworker, a boss, a spouse, etc. In each of these interpersonal relationships, we generally see ourselves as having long-term relationships with these people that we want to succeed. Notice, though, that if you’re arguing with a random person on a subway, that will not fall into this definition because of the interdependence factor. We may have disagreements and arguments with all kinds of strangers, but those don’t rise to the level of interpersonal conflicts.

People Perceive Differing Goals/Outcomes of Means to the Same Ends

An incompatible goal occurs when two people want different things. For example, imagine you and your best friend are thinking about going to the movies. They want to see a big-budget superhero film, and you’re more in the mood for an independent artsy film. In this case, you have pretty incompatible goals (movie choices). You can also have incompatible means to reach the same end. Incompatible means, in this case, “occur when we want to achieve the same goal but differ in how we should do so.”14 For example, you and your best friend agree on going to the same movie, but not about at which theatre you should see the film.

Conflict Can Negatively Affect the Relationship if Not Addressed

Next, interpersonal conflicts can lead to very negative outcomes if the conflicts are not managed effectively. Here are some examples of conflicts that are not managed effectively:

- One partner dominates the conflict, and the other partner caves-in.

- One partner yells or belittles the other partner.

- One partner uses half-truths or lies to get her/his/their way during the conflict.

- Both partners only want to get their way at all costs.

- One partner refuses to engage in conflict.

- Etc.

Again, this is a sample laundry list of some of the ways where conflict can be mismanaged. When conflict is mismanaged, one or both partners can start to have less affinity for the other partner, which can lead to a decreasing in liking, decreased caring about the relational partner, increased desire to exit the relationship, increased relational apathy, increased revenge-seeking behavior, etc. All of these negative outcomes could ultimately lead to conflicts becoming increasingly more aggressive (both active and passive) or just outright conflict avoidance. We’ll look at both of these later in the chapter.

Some Sense of Urgency to Resolve Conflict

Lastly, there must be some sense of urgency to resolve the conflict within the relationship. The conflict gets to the point where it must receive attention, and a decision must be made or an outcome decided upon, or else. If a conflict reaches the point where it’s not solved, then the conflict could become more problematic and negative if it’s not dealt with urgently.

Now, some people let conflicts stir and rise over many years that can eventually boil over, but these types of conflicts when they arise generally have some other kind of underlying conflict that is causing the sudden explosion. For example, imagine your spouse has a particularly quirky habit. For the most part, you ignore this habit and may even make a joke about the habit. Finally, one day you just explode and demand the habit must change. Now, it’s possible that you let this conflict build for so long that it finally explodes. It’s kind of like a geyser. According to Yellowstone National Park, here’s how a geyser works:

The looping chambers trap steam from the hot water. Escaped bubbles from trapped steam heat the water column to the boiling point. When the pressure from the trapped steam builds enough, it blasts, releasing the pressure. As the entire water column boils out of the ground, more than half the volume is this steam. The eruption stops when the water cools below the boiling point.15

In the same way, sometimes people let irritations or underlying conflict percolate inside of them until they reach a boiling point, which leads to the eventual release of pressure in the form of a sudden, out of nowhere conflict. In this case, even though the conflict has been building for some time, the eventual desire to make this conflict known to the other person does cause an immediate sense of urgency for the conflict to be solved.

Key Takeaways

- The terms disagreement and argument are often confused with one another. For our purposes, the terms refer to unique concepts. A disagreement is a difference of opinion between two or more people or groups of people; whereas, an argument is a verbal exchange between two or more people who have differing opinions on a given subject or subjects.

- There are two general perspectives regarding the nature of conflict. The first perspective sees conflict as a disruption to normal working systems, so conflict is inherently something that is dangerous to relationships and should be avoided. The second perspective sees conflict as a normal, inevitable part of any relationship. From this perspective, conflict is a tool that can either be used constructively or destructively in relationships.

- According to Cahn and Abigail, interpersonal conflict consists of four unique parts: 1) interdependence between or among the conflict parties, (2) incompatible goals/means, (3) conflict can adversely affect a relationship if not handled effectively, and (4) there is a sense of urgency to resolve the conflict.

Exercises

- On a sheet of paper, write out what you believe are the pros and cons of both major perspectives about conflict. Which one do you think describes your own understanding of conflict? Do you think they are both applicable to interpersonal conflict?

- Think of a time when you’ve engaged in conflict with a relational partner of some kind (parent/guardian, child, sibling, spouse, friend, romantic partner, etc.). Using Cahn and Abigail’s four parts of interpersonal conflict, dissect the conflict and explain why it would qualify as an interpersonal conflict.

- We know that different people have different levels of tolerance for disagreement in life. How do you think an individual’s tolerance for disagreement impacts her/his/their ability to interact with others interpersonally?

9.2 Emotions and Feelings

Learning Objectives

- Explain the interrelationships among emotions and feelings.

- Describe emotional awareness and its importance to interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate between “I” and “You” statements.

- Explain the concept of emotional intelligence.

To start our examination of the idea of emotions and feelings and how they relate to harmony and discord in a relationship, it’s important to differentiate between emotions and feelings. Emotions are our reactions to stimuli in the outside environment. Emotions, therefore, can be objectively measured by blood flow, brain activity, and nonverbal reactions to things. Feelings, on the other hand, are the responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality. So, there is an inherent relationship between emotions and feelings, but we do differentiate between them. Table 9.1 breaks down the differences between the two concepts.

| © John W. Voris, CEO of Authentic Systems, www.authentic-systems.com Reprinted here with permission. |

|

| Feelings: | Emotions: |

|---|---|

| Feelings tell us “how to live.” | Emotions tell us what we “like” and “dislike.” |

| Feelings state: “There is a right and wrong way to be.“ | Emotions state: “There are good and bad actions.” |

| Feelings state: “your emotions matter.” | Emotions state: “The external world matters.” |

| Feelings establish our long-term attitude toward reality. | Emotions establish our initial attitude toward reality. |

| Feelings alert us to anticipated dangers and prepares us for action. | Emotions alert us to immediate dangers and prepare us for action. |

| Feelings ensure long-term survival of self (body and mind). | Emotions ensure immediate survival of self (body and mind). |

| Feelings are Low-key but Sustainable. | Emotions are Intense but Temporary. |

| Happiness: is a feeling. | Joy: is an emotion. |

| Worry: is a feeling. | Fear: is an emotion. |

| Contentment: is a feeling. | Enthusiasm: is an emotion. |

| Bitterness: is a feeling. | Anger: is an emotion. |

| Love: is a feeling. | Lust: is an emotion. |

| Depression: is a feeling. | Sadness: is an emotion. |

Table 9.1 The Differences of Emotions and Feelings

It’s important to understand that we are all allowed to be emotional beings. Being emotional is an inherent part of being a human. For this reason, it’s important to avoid phrases like “don’t feel that way” or “they have no right to feel that way.” Again, our emotions are our emotions, and, when we negate someone else’s emotions, we are negating that person as an individual and taking away their right to emotional responses. At the same time, though, no one else can make you “feel” a specific way. Our emotions are our emotions. They are how we interpret and cope with life. A person may set up a context where you experience an emotion, but you are the one who is still experiencing that emotion and allowing yourself to experience that emotion. If you don’t like “feeling” a specific way, then change it. We all have the ability to alter our emotions. Altering our emotional states (in a proactive way) is how we get through life. Maybe you just broke up with someone, and listening to music helps you work through the grief you are experiencing to get to a better place. For others, they need to openly communicate about how they are feeling in an effort to process and work through emotions. The worst thing a person can do is attempt to deny that the emotion exists.

Think of this like a balloon. With each breath of air you blow into the balloon, you are bottling up more and more emotions. Eventually, that balloon will get to a point where it cannot handle any more air in it before it explodes. Humans can be the same way with emotions when we bottle them up inside. The final breath of air in our emotional balloon doesn’t have to be big or intense. However, it can still cause tremendous emotional outpouring that is often very damaging to the person and their interpersonal relationships with others.

Other research has demonstrated that handling negative emotions during conflicts within a marriage (especially on the part of the wife) can lead to faster de-escalations of conflicts and faster conflict mediation between spouses.16

Emotional Awareness

Sadly, many people are just completely unaware of their own emotions. Emotional awareness, or an individual’s ability to clearly express, in words, what they are feeling and why, is an extremely important factor in effective interpersonal communication. Unfortunately, our emotional vocabulary is often quite limited. One extreme version of of not having an emotional vocabularly is called alexithymia, “a general deficit in emotional vocabulary—the ability to identify emotional feelings, differentiate emotional states from physical sensations, communicate feelings to others, and process emotion in a meaningful way.”17 Furthermore, there are many people who can accurately differentiate emotional states but lack the actual vocabulary for a wide range of different emotions. For some people, their emotional vocabulary may consist of good, bad, angry, and fine. Learning how to communicate one’s emotions is very important for effective interpersonal relationships.18 First, it’s important to distinguish between our emotional states and how we interpret an emotional state. For example, you can feel sad or depressed, but you really cannot feel alienated. Your sadness and depression may lead you to perceive yourself as alienated, but alienation is a perception of one’s self and not an actual emotional state. There are several evaluative terms that people ascribe themselves (usually in the process of blaming others for their feelings) that they label emotions, but which are in actuality evaluations and not emotions. Table 9.2 presents a list of common evaluative words that people confuse for emotional states.

Cornered

Mistreated

Scorned

Abused

Devalued

Misunderstood

Taken for granted

Affronted

Diminished

Neglected

Threatened

Alienated

Distrusted

Overworked

Thwarted

Attacked

Humiliated

Patronized

Tortured

Belittled

Injured

Pressured

Unappreciated

Betrayed

Interrupted

Provoked

Unheard

Boxed-in

Intimidated

Put away

Unseen

Bullied

Let down

Putdown

Unsupported

Cheated

Maligned

Rejected

Unwanted

Coerced

Manipulated

Ridiculed

Used

Co-opted

Mocked

Ruined

Wounded

Table 9.2 Evaluative Words Confused for Emotions

Instead, people need to avoid these evaluative words and learn how to communicate effectively using a wide range of emotions. Tables 9.3 and 9.4 provide a list of both positive and negative feelings that people can express. Go through the list considering the power of each emotion. Do you associate light, medium, or strong emotions with the words provided on these lists? Why? There is no right or wrong way to answer this question. Still, it is important to understand that people can differ in their interpretations of the strength of different emotionally laden words. If you don’t know what a word means, you should look it up and add another word to your list of feelings that you can express to others.

Eager

Happy

Rapturous

Adventurous

Ebullient

Helpful

Refreshed

Affectionate

Ecstatic

Hopeful

Relaxed

Aglow

Effervescent

Inquisitive

Relieved

Alert

Elated

Inspired

Sanguine

Alive

Enchanted

Intense

Satisfied

Amazed

Encouraged

Interested

Secure

Amused

Energetic

Intrigued

Sensitive

Animated

Engrossed

Invigorated

Serene

Appreciative

Enlivened

Involved

Spellbound

Ardent

Enthusiastic

Jovial

Splendid

Aroused

Euphoric

Joyous

Stimulated

Astonished

Excited

Jubilant

Sunny

Blissful

Exhilarated

Keyed-up

Surprised

Breathless

Expansive

Lively

Tender

Buoyant

Expectant

Loving

Thankful

Calm

Exultant

Mellow

Thrilled

Carefree

Fascinated

Merry

Tickled Pink

Cheerful

Free

Mirthful

Touched

Comfortable

Friendly

Moved

Tranquil

Complacent

Fulfilled

Optimistic

Trusting

Composed

Genial

Overwhelmed

Upbeat

Concerned

Glad

Peaceful

Vibrant

Confident

Gleeful

Perky

Warm

Content

Glorious

Pleasant

Wonderful

Cool

Glowing

Pleased

Zippy

Curious

Good-humored

Proud

Dazzled

Grateful

Quiet

Delighted

Gratified

Radiant

Table 9.3 Positive Emotions

Disgusted

Impatient

Sensitive

Aggravated

Disheartened

Indifferent

Shaky

Agitated

Dismayed

Intense

Shameful

Alarmed

Displeased

Irate

Shocked

Angry

Disquieted

Irked

Skeptical

Anguished

Disturbed

Irritated

Sleepy

Annoyed

Distressed

Jealous

Sorrowful

Antagonistic

Downcast

Jittery

Sorry

Anxious

Downhearted

Keyed-up

Spiritless

Apathetic

Dull

Lazy

Spiteful

Appalled

Edgy

Leery

Startled

Apprehensive

Embarrassed

Lethargic

Sullen

Aroused

Embittered

Listless

Surprised

Ashamed

Exasperated

Lonely

Suspicious

Beat

Exhausted

Mad

Tearful

Bewildered

Fatigued

Mean

Tepid

Bitter

Fearful

Melancholy

Terrified

Blah

Fidgety

Miserable

Ticked off

Blue

Forlorn

Mopey

Tired

Bored

Frightened

Morose

Troubled

Brokenhearted

Frustrated

Mournful

Uncomfortable

Chagrined

Furious

Nervous

Unconcerned

Cold

Galled

Nettled

Uneasy

Concerned

Gloomy

Numb

Unglued

Confused

Grim

Overwhelmed

Unhappy

Cool

Grouchy

Panicky

Unnerved

Crabby

Guilty

Passive

Unsteady

Cranky

Harried

Perplexed

Upset

Cross

Heavy

Pessimistic

Uptight

Dejected

Helpless

Petulant

Vexed

Depressed

Hesitant

Puzzled

Weary

Despairing

Hopeless

Rancorous

Weepy

Despondent

Horrified

Reluctant

Wistful

Detached

Horrible

Repelled

Withdrawn

Disaffected

Hostile

Resentful

Woeful

Disenchanted

Hot

Restless

Worried

Disappointed

Humdrum

Sad

Wretched

Discouraged

Hurt

Scared

Sensitive

Disgruntled

Ill-Tempered

Seething

Shaky

The Problem of You Statements

According to Marshall Rosenberg, the father of nonviolent communication, “You” statements ultimately are moralistic judgments where we imply the wrongness or badness of another person and the way they have behaved.19 When we make moralistic judgments about others, we tend to deny responsibility for our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Remember, when it comes to feelings, no one can “make” you feel a specific way. We choose the feelings we inhabit; we do not inhabit the feelings that choose us. When we make moralistic judgments and deny responsibility, we end up in a constant cycle of defensiveness where your individual needs are not going to be met by your relational partner. Behind every negative emotion is a need not being fulfilled, and when we start blaming others, those needs will keep getting unfilled in the process. Often this lack of need fulfillment will result in us demanding someone fulfill our need or face blame or punishment. For example, “if you go hang out with your friends tonight, I’m going to hurt myself and it will your fault.” In this simple sentence, we see someone who disapproves of another’s behaviors and threatens to blame their relational partner for the individual’s behavior. In highly volatile relationships, this constant blame cycle can become very detrimental, and no one’s needs are getting met.

However, just observing behavior and stating how you feel only gets you part of the way there because you’re still not describing your need. Now, when we talk about the idea of “needing” something, we are not talking about this strictly in terms of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, though those are all entirely appropriate needs. At the same time, relational needs are generally not rewards like tangible items or money. Instead, Marshall Rosenberg categorizes basic needs that we all have falling into the categories: autonomy, celebration, play, spiritual communion, physical nurturance, integrity, and interdependence (Table 9.5). As you can imagine, any time these needs are not being met, you will reach out to get them fulfilled. As such, when we communicate about our feelings, they are generally tied to an unmet or fulfilled need. For example, you could say, “I feel dejected when you yell at me because I need to be respected.” In this sentence, you are identifying your need, observing the behavior, and labeling the need. Notice that there isn’t judgment associated with identifying one’s needs.

| Area | Need |

|---|---|

| Autonomy | to choose one’s dreams, goals, values |

| to choose one’s plan for fulfilling one’s dreams, goals, values | |

| Celebration | to celebrate the creation of life and dreams fulfilled |

| to celebrate losses: loved ones, dreams, etc. (mourning) | |

| Play | fun |

| laughter | |

| Spiritual Communion | beauty |

| harmony | |

| inspiration | |

| order | |

| peace | |

| Physical Nurturance | air |

| food | |

| movement, exercise | |

| protection from life-threatening forms of life: viruses, bacteria, insects, predatory animals | |

| rest | |

| sexual expression | |

| shelter | |

| touch | |

| water | |

| Integrity | authenticity |

| creativity | |

| meaning | |

| self-worth | |

| Interdependence | acceptance |

| appreciation | |

| closeness | |

| community | |

| consideration | |

| contribution to the enrichment of life (to exercise one’s power by giving that which contributes to life) | |

| emotional safety | |

| empathy | |

| honesty (the empowering honest that enables us to learn from our limitations) | |

| love | |

| reassurance | |

| respect | |

| support | |

| trust | |

| understanding | |

| warmth | |

| Source: Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life 2nd Ed by Dr. Marshall B. Rosenberg, 2003–published by PuddleDancer Press and Used with Permission. For more information visit www.CNVC.org and www.NonviolentCommunication.com |

|

Table 9.5 Needs

Emotional Intelligence

In Chapter 3, we first discussed the concept of emotional intelligence. However, it’s important to revisit this concept before we move on. In Chapter 3, we defined emotional intelligence(EQ) as an individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions. Furthermore, we learned that EQ is built by four distinct emotional processes: perceiving, understanding, managing, and using emotions.20 Although we are talking about the importance of EQ, take a minute and complete Table 9.6, which is a simple 20-item questionnaire designed to help you evaluate your own EQ.

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with your perception. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____1. I am aware of my emotions as I experience them.

_____2. I easily recognize my emotions.

_____3. I can tell how others are feeling simply by watching their body movements.

_____4. I can tell how others are feeling by listening to their voices.

_____5. When I look at people’s faces, I generally know how they are feeling.

_____6. When my emotions change, I know why.

_____7. I understand that my emotional state is rarely comprised of one single emotion.

_____8. When I am experiencing an emotion, I have no problem easily labeling that emotion.

_____9. It’s completely possible to experience two opposite emotions at the same time (e.g., love & hate; awe & fear; joy & sadness, etc.).

_____10. I can generally tell when my emotional state is shifting from one emotion to another.

_____11. I don’t let my emotions get the best of me.

_____12. I have control over my own emotions.

_____13. I can analyze my emotions and determine if they are reasonable or not.

_____14. I can engage or detach from an emotion depending on whether I find it informative or useful.

_____15. When I’m feeling sad, I know how to seek out activities that will make me happy.

_____16. I can create situations that will cause others to experience specific emotions.

_____17. I can use my understanding of emotions to have more productive interactions with others.

_____18. I know how to make other people happy or sad.

_____19. I often lift people’s spirits when they are feeling down.

_____20. I know how to generate negative emotions and enhance pleasant ones in my interactions with others.

Scoring:

| Perceiving Emotions | Add scores for items 1, 2, 3, 4, & 5 | = | ||

| Understanding Emotions | Add scores for items 6, 7, 8, 9, & 10 | = | ||

| Managing Emotions | Add scores for items 11, 12, 13, 14, & 15 | = | ||

| Using Emotions | Add scores for items 16, 17, 18, 19, & 20 | = | ||

Interpreting Your Scores:

Each of the four parts of the EQ Model can have a range of 5 to 25. Scores under 11 represent low levels of EQ for each aspect. Scores between 12 and 18 represent average levels of EQ. Scores 19 and higher represent high levels of EQ.

Table 9.6 Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire

Research Spotlight

In 2020, researchers Anna Wollny, Ingo Jacobs, and Luise Pabel set out to examine the impact that trait EQ has on both relationship satisfaction and dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is based on Guy Bodenmann’s Systemic Transactional Model (STM), which predicts that stress in dyadic relationships is felt by both partners.21 So, if one partner experiences the stress of a job loss, that stress really impacts both partners. As a result, both partners can engage in mutual shared problem-solving or joint emotion-regulation.22 According to Bodenmann, there are three different common forms of dyadic coping:

In 2020, researchers Anna Wollny, Ingo Jacobs, and Luise Pabel set out to examine the impact that trait EQ has on both relationship satisfaction and dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is based on Guy Bodenmann’s Systemic Transactional Model (STM), which predicts that stress in dyadic relationships is felt by both partners.21 So, if one partner experiences the stress of a job loss, that stress really impacts both partners. As a result, both partners can engage in mutual shared problem-solving or joint emotion-regulation.22 According to Bodenmann, there are three different common forms of dyadic coping:

- Positive dyadic coping involves the provision of problem- and emotion-focused support and reducing the partner’s stress by a new division of responsibilities and contributions to the coping process.

- Common dyadic coping (i.e., joint dyadic coping) includes strategies in which both partners jointly engage to reduce stress (e.g., exchange tenderness, joint problem-solving).

- Negative dyadic coping comprises insufficient support and ambivalent or hostile intervention attempts (e.g., reluctant provision of support while believing that the partner should solve the problem alone).23

In the Wollny et al. (2000) study, the researchers studied 136 heterosexual couples. Trait EQ was positively related to relationship satisfaction. Trait EQ was positively related to positive dyadic coping and common dyadic coping but not related to negative dyadic coping.

Wollny, A., Jacobs, I., & Pabel, L. (2020, 2020/01/02). Trait emotional intelligence and relationship satisfaction: The mediating role of dyadic coping. The Journal of Psychology, 154(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2019.1661343

Letting Go of Negative Thoughts

We often refer to these negative thoughts as vulture statements (as discussed in Chapter 3).24 Some of us have huge, gigantic vultures sitting on our shoulders every day, and we keep feeding them with all of our negative thoughts. Right when that thought enters your head, you have started to feed that vulture sitting on your shoulders.

Unfortunately, many of us will focus on that negative thought and keep that negative thought in our heads for a long period. It’s like have a bag full of carrion, and we just keep lifting it to the vulture, who just keeps getting fatter and fatter, weighing you down more and more.

Every time we point out a negative thought instead of harping on that thought, we take a pause and stop feeding the vulture. Do this long enough, and you will see the benefits to your self-concept. Furthermore, when we have a healthy self-concept, we also have stronger interpersonal relationships.25

Positive Emotions During Conflict

Researchers have found that serious relationship problems arise when those in the relationship are unable to reach beyond the immediate conflict and include positive as well as negative emotions in their discussions. In a landmark study of newlywed couples, for example, researchers attempted to predict who would have a happy marriage versus an unhappy marriage or a divorce, based on how the newlyweds communicated with each other. Specifically, they created a stressful conflict situation for couples. The researchers then evaluated how many times the newlyweds expressed positive emotions and how many times they expressed negative emotions in talking with each other about the situation.

When the marital status and happiness of each couple were evaluated over the next six years, the study found that the strongest predictor of a marriage that stayed together and was happy was the degree of positive emotions expressed during the conflict situation in the initial interview.26

In happy marriages, instead of always responding to anger with anger, the couples found a way to lighten the tension and to de-escalate the conflict. In long-lasting marriages, during stressful times or in the middle of conflict, couples were able to interject some positive comments and positive regard for each other. When this finding is generalized to other types of interpersonal relationships, it makes a strong case for having some positive interactions, interjecting some humor, some light-hearted fun, or some playfulness into your conversation while you are trying to resolve conflicts.

Key Takeaways

- Emotions are our physical reactions to stimuli in the outside environment; whereas, feelings are the responses to thoughts and interpretations given to emotions based on experiences, memory, expectations, and personality.

- Emotional awareness involves an individual’s ability to recognize their feelings and communicate about them effectively. One of the common problems that some people have with regards to emotional awareness is a lack of a concrete emotional vocabulary for both positive and negative feelings. When people cannot adequately communicate about their feelings, they will never get what they need out of a relationship.

- One common problem in interpersonal communication is the overuse of “You” statements. “I” statements are statements that take responsibility for how one is feeling. “You” statements are statements that place the blame of one’s feelings on another person. Remember, another person cannot make you feel a specific way. Furthermore, when we communicate “you” statements, people tend to become more defensive, which could escalate into conflict.

- Emotional intelligence is the degree to which an individual has the ability to perceive (recognizing emotions when they occur), understand (the ability to understand why emotions and feelings arise), communicate (articulating one’s emotions and feelings to another person), and manage emotions and feelings (being able to use emotions effectively during interpersonal relationships).

Exercises

- Think of an extreme emotion you’ve felt recently. Explain the interrelationships between that emotion, your thoughts, and your feelings when you experienced that extreme emotion.

- Complete the Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire. What areas are your strenghts with regard to EQ? What areas are your weaknesses? How can you go about improving your strengths while alleviating your weaknesses?

- Think of a conflict you’ve had with a significant other in your relationship. How many of the statements that were made during that conflict were “You” statements as compared to “I” statements? How could you have more clearly expressed your feelings and link them to your needs?

9.3 Power and Influence

Learning Objectives

- Define the term “influence” and explain the three levels of influence.

- Define the word “power” and explain the six bases of power.

One of the primary reasons we engage in a variety of interpersonal relationships over our lifetimes is to influence others. We live in a world where we constantly need to accomplish a variety of goals, so being able to get others to jump on board with our goals is a very important part of social survival. As such, we define influence when an individual or group of people alters another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors through accidental, expressive, or rhetorical communication.27 Notice this definition of influence is one that focuses on the importance of communication within the interaction. Within this definition, we discuss three specific types of communication: accidental, expressive, or rhetorical.

First, we have accidental communication, or when we send messages to another person without realizing those messages are being sent. Imagine you are walking through your campus’ food court and notice a table set up for a specific charity. A person who we really respect is hanging out at the table laughing and smiling, so you decide to donate a dollar to the charity. The person who was just hanging out at the table influenced your decision to donate. They could have just been talking to another friend and may not have even really been a supporter of the charity, but their presence was enough to influence your donation. At the same time, we often influence others to think, feel, and behave in ways they wouldn’t have unconsciously. A smile, a frown, a head nod, or eye eversion can all be nonverbal indicators to other people, which could influence them. There’s a great commercial on television that demonstrates this. The commercial starts with someone holding the door for another person, then this person turns around and does something kind to another person, and this “paying it forward” continues through the entire commercial. In each incident, no one said to the person they were helping to “pay it forward,” they just did.

The second type of communication we can have is expressive or emotionally-based communication. Our emotional states can often influence other people. If we are happy, others can become happy, and if we are sad, others may avoid us altogether. Maybe you’ve walked into a room and seen someone crying, so you ask, “Are you OK?” Instead of responding, the person just turns and glowers at you, so you turn around and leave. With just one look, this person influenced your behavior.

The final type of communication, rhetorical communication, involves purposefully creating and sending messages to another person in the hopes of altering another person’s thinking, feelings, and/or behaviors. Accidental communication is not planned. Expressive communication is often not conscious at all. However, rhetorical communication is purposeful. When we are using rhetorical communication to influence another person(s), we know that we are trying to influence that person(s).

Levels of Influence

In 1958 social psychologist Herbert Kelman first noted that there are three basic levels of influence: compliance, identification, and internalization.28 Kelman’s basic theory was that changes in a person’s thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors occur at different levels, which results in different processes an individual uses to achieve conformity with an influencer. Let’s look at each of these three levels separately.

Compliance

The first, and weakest, form of influence is compliance. Compliance implies that an individual accepts influence and alters their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. However, this change in thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors is transitory and only lasts as long as the individual sees compliance as beneficial.29 Generally, people accept influence at this level because they perceive the rewards or punishments for influence to be in their best interest. As such, this form of influence is very superficial.30

Identification

The second form of influence discussed by Kelman is identification, which is based purely in the realm of relationships. Identification occurs when an individual accepts influence because they want to have a satisfying relationship with the influencer or influencing group. “The individual actually believes in the responses which he [or she] adopts through identification, but their specific content is more or less irrelevant. He [or she] adopts the induced behavior because it is associated with the desired relationship. Thus the satisfaction derived from identification due to the act of conforming as such.”31 Notice that Kelman is arguing that the actual change to thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors is less of an issue that the relationship and the act of conforming. However, if an individual ever decides that the relationship and identification with the influencing individual or group are not beneficial, then the influencing attempts will disappear, and the individual will naturally go back to their original thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors.

Internalization

The final level of influence proposed by Kelman is internalization, which occurs when an individual adopts influence and alters their thinking, feeling, and/or behaviors because doing so is intrinsically rewarding. Ultimately, changing one’s thinking, feelings, and/or behavior happens at the internalization level because an individual sees this change as either coinciding with their value system, considers the change useful, or fulfills a need the individual has. Influence that happens at this level becomes highly intertwined with the individual’s perception of self, so this type of influence tends to be long-lasting.

French & Raven’s Five Bases of Power

When you hear the word “power,” what comes to mind? Maybe you think of a powerful person like a Superhero or the President of the United States. For social scientists, we use the word “power” in a very specific way. Power is the degree that a social agent (A) has the ability to get another person(s) (P) to alter their thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. First, you have a social agent (A), which can come in a variety of different forms: another person, a role someone embodies, a group rule or norm, or a group or part of a group.32 Next, we have the person(s) who is being influenced by the goal to be a specific change in thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. When we discussed influence above, we talked about it in terms of communication: accidental, expressive, and rhetorical. When we deal with power, we are only dealing in the realm of rhetorical communication because the person exerting power over another person is consciously goal-directed.

Probably the most important people in the realm of power have been John French and Bertram Raven. In 1959, French and Raven identified five unique bases of power that people can use to influence others (coercive, reward, legitimate, expert, and referent).33 At the time of their original publication, there was a sixth base of power that Raven attempted to argue for, informational. Although he lost the battle in the initial publication, subsequent research by Raven on the subject of the bases of power have all included informational power.34 Let’s examine each of these five bases of power.

Informational

The first basis of power is the last one originally proposed by Raven.35 Informational power refers to a social agent’s ability to bring about a change in thought, feeling, and/or behavior through information. For example, since you initially started school, teachers have had informational power over you. They have provided you with a range of information on history, science, grammar, art, etc. that shape how you think (what constitutes history?), feel (what does it mean to be aesthetically pleasing?), and behave (how do you properly mix chemicals in a lab?). In some ways, informational power is very strong, because it’s often the first form of power with which we come into contact. In fact, when you are taught how to think, feel, and/or behave, this change “now continues without the target necessarily referring to, or even remembering, the [influencer] as being the agent of change.”36

Coercive and Reward

The second base of power is coercive power, which is the ability to punish an individual who does not comply with one’s influencing attempts. On the other end of the spectrum, we have reward power (3rd base of power), which is the ability to offer an individual rewards for complying with one’s influencing attempts. We talk about these two bases of power together because they are two sides of the same coin. Furthermore, the same problems with this type of power apply equally to both. Influence can happen if you punish or reward someone; however, as soon as you take away that punishment or reward, the thoughts, feelings, and/or behavior will reverse back to its initial state. Hence, we refer to both coercive and reward power as attempts to get someone to comply with influence, because this is the highest level of influence one can hope to achieve with these two forms of power.

Legitimate

The fourth base of power is legitimate power, or influence that occurs because a person (P) believes that the social agent (A) has a valid right to influence P, and P has an obligation to accept A’s attempt to influence P’s thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors. French and Raven argued that there were two common forms of legitimate power: cultural and structural. Cultural legitimate power occurs when a change agent is viewed as having the right to influence others because of their role in the culture. For example, in some cultures, the elderly may have a stronger right to influence than younger members of that culture. Structural legitimate power, on the other hand, occurs because someone fulfills a specific position within the social hierarchy. For example, your boss may have the legitimate right to influence your thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors in the workplace because they are above you in the organizational hierarchy.37

Expert

The fifth base of power is expert power, or the power we give an individual to influence us because of their perceived knowledge. For example, we often give our physicians the ability to influence our behavior (e.g., eat right, exercise, take medication, etc.) because we view these individuals as having specialized knowledge. However, this type of influence only is effective if P believes A is an expert, P trusts A, and P believes that A is telling the truth.

One problem we often face in the 21st Century involves the conceptualization of the word “expert.” Many people in today’s world can be perceived as “experts” just because they write a book, have a talk show, were on a reality TV show, or are seen on news programs.38 Many of these so-called “experts” may have no reasonable skill or knowledge but they can be trumpeted as experts. One of the problems with the Internet is the fundamental flaw that anyone can put information online with only an opinion and no actual facts. Additionally, we often engage in debates about “facts” because we have different talking heads telling us different information. Historically, expert power was always a very strong form of power, but there is growing concern that we are losing expertise and knowledge to unsubstantiated opinions and rumor mongering.

At the same time, there is quite a bit of research demonstrating that many people are either unskilled or unknowledgeable and completely unaware of their lack of expertise. This problem has been called the Dunning–Kruger effect, or the tendency of some people to inflate their expertise when they really have nothing to back up that perception.39 As you can imagine, having a lot of people who think they are experts spouting off information that is untrue can be highly problematic in society. For example, do you really want to take medical advice from a TV star? Many people do. While we have some people who inflate their expertise, on the other end of the spectrum, some people suffer from imposter syndrome, which occurs when people devalue or simply do not recognize their knowledge and skills. Imposter syndrome is generally a problem with highly educated people like doctors, lawyers, professors, business executives, etc. The fear is that someone will find out that they are a fraud.

Referent

The final base of power originally discussed by French and Raven is referent power, or a social agent’s ability to influence another person because P wants to be associated with A. Ultimately, referent power is about relationship building and the desire for a relationship. If A is a person P finds attractive, then P will do whatever they need to do to become associated with A. If A belongs to a group, then P will want to join that group. Ultimately, this relationship exists because P wants to think, feel, and behave as A does. For example, if A decides that he likes modern art, then P will also decide to like modern art. If A has a very strong work ethic in the workplace, then P will adopt a strong work ethic in the workplace as well. Often A has no idea of the influence they are having over P. Ultimately, the stronger P desires to be associated with A, the more referent power A has over P.

Influence and Power

By now, you may be wondering about the relationship between influence and power. Research has examined the relationship between the three levels of influence and the six bases of power. Coercive, reward, and legitimate power only influence people at the compliance level. Whereas, informational, expert, and referent power have been shown to influence people at all three levels of influence: compliance, identification, and internalization.40 When you think about your own interpersonal influencing goals, you really need to consider what level of influence you desire a person’s change in thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors to be. If your goal is just to get the change quickly, then using coercive, reward, and legitimate power may be the best route. If, however, you want to ensure long-term influence, then using informational, expert, and referent power are probably the best routes to use.

Research Spotlight

In 2013, Shireen Abuhatoum and Nina Howe set out to explore how siblings use French and Raven’s bases of power in their relationships. Specifically, they examined how older siblings (average age of 7 years old) interacted with their younger siblings (average age was 4 ½ years old). Sibling pairs were recorded playing at home with a wooden farm set that was provided for the observational study. Each recorded video lasted for 15-minutes. The researchers then coded the children’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors. The goal was to see what types of power strategies the siblings employed while playing.

In 2013, Shireen Abuhatoum and Nina Howe set out to explore how siblings use French and Raven’s bases of power in their relationships. Specifically, they examined how older siblings (average age of 7 years old) interacted with their younger siblings (average age was 4 ½ years old). Sibling pairs were recorded playing at home with a wooden farm set that was provided for the observational study. Each recorded video lasted for 15-minutes. The researchers then coded the children’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors. The goal was to see what types of power strategies the siblings employed while playing.

Unsurprisingly, older siblings were more likely to engage in power displays with their younger siblings to get what they wanted. However, younger siblings were more likely to appeal to a third party (usually an adult) to get their way.

The researchers also noted that when it came to getting a desired piece of the farm to play with, older siblings were more likely to use coercive power. Younger siblings were more likely to employ legitimate power as an attempt to achieve a compromise.

Abuhatoum, S., & Howe, N. (2013). Power in sibling conflict during early and middle childhood. Social Development, 22(4), 738–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12021

Key Takeaways

- Herbert Kelman noted that there are three basic levels of influence: compliance (getting someone to alter behavior), identification (altering someone’s behavior because they want to be identified with a person or group), and internalization (influence that occurs because someone wants to be in a relationship with an influencer).

- French and Raven have devised six basic bases of power: informational, coercive, reward, legitimate, expert, and referent. First, we have informational power, or the power we have over others as we provide them knowledge. Second, we have coercive power, or the ability to punish someone for noncompliance. Third, we have reward power, or the ability to reward someone for compliance. Fourth we have legitimate power, or power someone has because of their position within a culture or a hierarchical structure. Fifth, we have expert power, or power that someone exerts because they are perceived as having specific knowledge or skills. Lastly, we have referent power, or power that occurs because an individual wants to be associated with another person.

Exercises

- Think of a time when you’ve been influenced at all three of Kelman’s levels of influence. How were each of these situations of influence different from each other? How were the different levels of influence achieved?

- Think of each of the following situations and which form of power would best be used and why:

- A mother wants her child to eat his vegetables.

- A police officer wants to influence people to slow down in residential neighborhoods.

- The Surgeon General of the United States wants people to become more aware of the problems of transsaturated fats in their diets.

- A friend wants to influence his best friend to stop doing drugs.

9.4 Conflict Management Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between conflict and disagreement.

- Explain the three common styles of conflict management.

- Summarize the STLC Model of Conflict.

Many researchers have attempted to understand how humans handle conflict with one another. The first researchers to create a taxonomy for understanding conflict management strategies were Richard E. Walton and Robert B. McKersie.41 Walton and McKersie were primarily interested in how individuals handle conflict during labor negotiations. The Walton and McKersie model consisted of only two methods for managing conflict: integrative and distributive. Integrative conflict is a win-win approach to conflict; whereby, both parties attempt to come to a settled agreement that is mutually beneficial. Distributive conflict is a win-lose approach; whereby, conflicting parties see their job as to win and make sure the other person or group loses. Most professional schools teach that integrative negotiation tactics are generally the best ones.

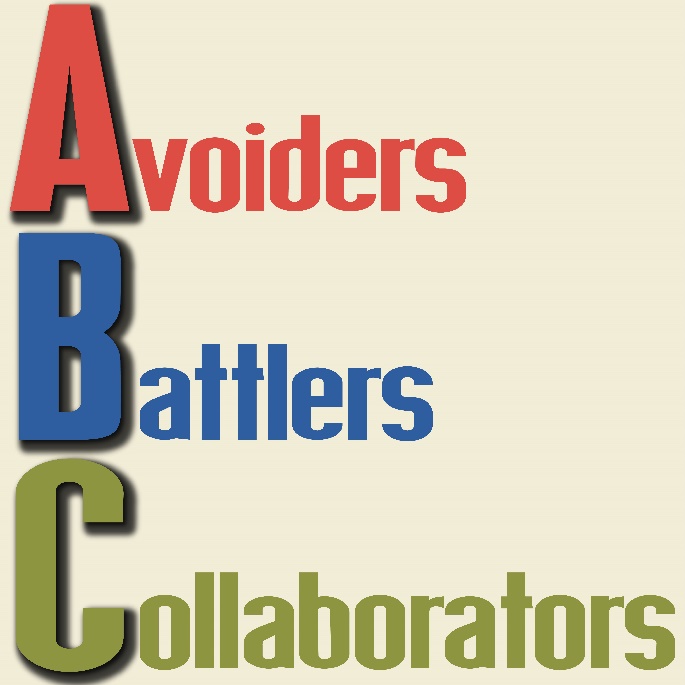

ABC’s of Conflict

Over the years, a number of different patterns for handling conflict have arisen in the literature, but most of them agree with the first two proposed by Walton and McKersie, but they generally add a third dimension of conflict: avoidance. Go ahead and take a moment to complete the questionnaire in Table 9.7.

Instructions: Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you typically behave when engaged in conflict with another person. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you.

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

When I start to engage in a conflict, I _______________

_____1. Keep the conflict to myself to avoid rocking the boat.

_____2. Do my best to win.

_____3. Try to find a solution that works for everyone.

_____4. Do my best to stay away from disagreements that arise.

_____5. Create a strategy to ensure my successful outcome.

_____6. Try to find a solution that is beneficial for those involved.

_____7. Avoid the individual with whom I’m having the conflict.

_____8. Won’t back down unless I get what I want.

_____9. Collaborate with others to find an outcome OK for everyone.

_____10. Leave the room to avoid dealing with the issue.

_____11. Take no prisoners.

_____12. Find solutions that satisfy everyone’s expectations.

_____13. Shut down and shut up in order to get it over with as quickly as possible.

_____14. See it as an opportunity to get what I want.

_____15. Try to integrate everyone’s ideas to come up with the best solution for everyone.

_____16. Keep my disagreements to myself.

_____17. Don’t let up until I win.

_____18. Openly raise everyone’s concerns to ensure the best outcome possible.

Scoring:

Avoiders

Add Items 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16______

Battlers

Add Items 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17______

Collaborators

Add Items 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18______

Interpretation: Scores for each subscale should range from 6 to 30. Scores under 14 are considered low, scores 15 to 23 are considered moderate, and scores over 24 are considered high.

Table 9.7 ABC’s of Conflict Management

Avoiders

Alan Sillars, Stephen, Coletti, Doug Parry, and Mark Rogers created a taxonomy of different types of strategies that people can use when avoiding conflict. Table 9.8 provides a list of these common tactics. 42

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Denial | Statements that deny the conflict. | “No, I’m perfectly fine.” |

| Extended Denial | Statements that deny conflict with a short justification. | “No, I’m perfectly fine. I just had a long night.” |

| Underresponsiveness | Statements that deny the conflict and then pose a question to the conflict partner. | “I don’t know why you are upset, did you wake up on the wrong side of the bed this morning?” |

| Topic Shifting | Statements that shift the interaction away from the conflict. | “Sorry to hear that. Did you hear about the mall opening?” |

| Topic Avoidance | Statements designed to clearly stop the conflict. | “I don’t want to deal with this right now.” |

| Abstractness | Statements designed to shift a conflict from concrete factors to more abstract ones. | “Yes, I know I’m late. But what is time really except a construction of humans to force conformity.” |

| Semantic Focus | Statements focused on the denotative and connotative definitions of words. | “So, what do you mean by the word ‘sex’?” |

| Process Focus | Statements focused on the “appropriate” procedures for handling conflict. | “I refuse to talk to you when you are angry.” |

| Joking | Humorous statements designed to derail conflict. | “That’s about as useless as a football bat.” |

| Ambivalence | Statements designed to indicate a lack of caring. | “Whatever!” “Just do what you want.” |

| Pessimism | Statements that devalue the purpose of conflict. | “What’s the point of fighting over this? Neither of us are changing our minds.” |

| Evasion | Statements designed to shift the focus of the conflict. | “I hear the Joneses down the street have that problem, not us.” |

| Stalling | Statements designed to shift the conflict to another time. | “I don’t have time to talk about this right now.” |

| Irrelevant Remark | Statements that have nothing to do with the conflict. | “I never knew the wallpaper in here had flowers on it.” |

Table 9.8 Avoidant Conflict Management Strategies

Battlers

For our purposes, we have opted to describe those who engage in distributive conflict as battlers because they often see going into a conflict as heading off to war, which is most appropriately aligned with the distributive conflict management strategies. Battlers believe that conflict should take on an approach where the battler must win the conflict at all costs without regard to the damage they might cause along the way. Furthermore, battlers tend to be very personalistic in their goals and are often highly antagonistic towards those individuals with whom they are engaging in conflict.43

Alan Sillars, Stephen, Coletti, Doug Parry, and Mark Rogers created a taxonomy of different types of strategies that people can use when using distributive conflict management strategies. Table 9.9 provides a list of these common tactics. 44

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Faulting | Statements that verbally criticize a partner. | “Wow, I can’t believe you are so dense at times.” |

| Rejection | Statements that express antagonistic disagreement. | “That is such a dumb idea.” |

| Hostile Questioning | Questions designed to fault a partner. | “Who died and made you king?” |

| Hostile Joking | Humorous statements designed to attack a partner. | “I do believe a village has lost its idiot.” |

| Presumptive Attribution | Statements designed to point the meaning or origin of the conflict to another source. | “You just think that because your father keeps telling you that.” |

| Avoiding Responsibility | Statements that deny fault. | “Not my fault, not my problem.” |

| Prescription | Statements that describe a specific change to another’s behavior. | “You know, if you’d just stop yelling, maybe people would take you seriously.” |

| Threat | Statements designed to inform a partner of a future punishment. | “You either tell your mother we’re not coming, or I’m getting a divorce attorney.” |

| Blame | Statements that lay culpability for a problem on a partner. | “It’s your fault we got ourselves in this mess in the first place.” |

| Shouting | Statements delivered in a manner with an increased volume. | “DAMMIT! GET YOUR ACT TOGETHER!” |

| Sarcasm | Statements involving the use of irony to convey contempt, mock, insult, or wound another person. | “The trouble with you is that you lack the power of conversation but not the power of speech.” |

Table 9.9 Distributive Conflict Management Strategies

Collaborators

The last type of conflicting partners are collaborators. There are a range of collaborating choices, from being completely collaborative in an attempt to find a mutually agreed upon solution, to being compromising when you realize that both sides will need to win and lose a little to come to a satisfactory solution. In both cases, the goal is to use prosocial communicative behaviors in an attempt to reach a solution everyone is happy with. Admittedly, this is often easier said than done. Furthermore, it’s entirely possible that one side says they want to collaborate, and the other side refuses to collaborate at all. When this happens, collaborative conflict management strategies may not be as effective, because it’s hard to collaborate with someone who truly believes you need to lose the conflict.

Alan Sillars, Stephen, Coletti, Doug Parry, and Mark Rogers created a taxonomy of different types of strategies that people can use when collaborating during a conflict. Table 9.10 provides a list of these common tactics. 45

| Conflict Management Tactic | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Acts | Statements that describe obvious events or factors. | “Last time your sister babysat our kids, she yelled at them.” |

| Qualification | Statements that explicitly explain the conflict. | “I am upset because you didn’t come home last night.” |

| Disclosure | Statements that disclose one’s thoughts and feelings in a non-judgmental way. | “I get really worried when you don’t call and let me know where you are.” |

| Soliciting Disclosure | Questions that ask another person to disclose their thoughts and feelings. | “How do you feel about what I just said?” |

| Negative Inquiry | Statements allowing for the other person to identify your negative behaviors. | “What is it that I do that makes you yell at me?” |

| Empathy | Statements that indicate you understand and relate to the other person’s emotions and experiences. | “I know this isn’t easy for you.” |

| Emphasize Commonalities | Statements that highlight shared goals, aims, and values. | “We both want what’s best for our son.” |

| Accepting Responsibility | Statements acknowledging the part you play within a conflict. | “You’re right. I sometimes let my anger get the best of me.” |

| Initiating Problem-Solving | Statements designed to help the conflict come to a mutually agreed upon solution. | “So let’s brainstorm some ways that will help us solve this.” |

| Concession | Statements designed to give in or yield to a partner’s goals, aims, or values. | “I promise, I will make sure my homework is complete before I watch television.” |

Table 9.10 Integrative Conflict Management Strategies

Before we conclude this section, we do want to point out that conflict management strategies are often reciprocated by others. If you start a conflict in a highly competitive way, do not be surprised when your conflicting partner mirrors you and starts using distributive conflict management strategies in return. The same is also true for integrative conflict management strategies. When you start using integrative conflict management strategies, you can often deescalate a problematic conflict by using integrative conflict management strategies.46

STLC Conflict Model

Ruth Anna Abigail and Dudley Cahn created a very simple model when thinking about how we communicate during conflict.47 They called the model the STLC Conflict Model because it stands for stop, think, listen, and then communicate.

Stop

The first thing an individual needs to do when interacting with another person during conflict is to take the time to be present within the conflict itself. Too often, people engaged in a conflict say whatever enters their mind before they’ve really had a chance to process the message and think of the best strategies to use to send that message. Others end up talking past one another during a conflict because they simply are not paying attention to each other and the competing needs within the conflict. Communication problems often occur during conflict because people tend to react to conflict situations when they arise instead of being mindful and present during the conflict itself. For this reason, it’s always important to take a breath during a conflict and first stop.

Sometimes these “time outs” need to be physical. Maybe you need to leave the room and go for a brief walk to calm down, or maybe you just need to get a glass of water. Whatever you need to do, it’s important to take this break. This break takes you out of a “reactive stance into a proactive one.” 48

Think

Once you’ve stopped, you now have the ability to really think about what you are communicating. You want to think through the conflict itself. What is the conflict really about? Often people engage in conflicts about superficial items when there are truly much deeper issues that are being avoided. You also want to consider what possible causes led to the conflict and what possible courses of action you think are possible to conclude the conflict. Cahn and Abigail argue that there are four possible outcomes that can occur: do nothing, change yourself, change the other person, or change the situation.

First, you can simply sit back and avoid the conflict. Maybe you’re engaging in a conflict about politics with a family member, and this conflict is actually just going to make everyone mad. For this reason, you opt just to stop the conflict and change topics to avoid making people upset. One of our coauthors was at a funeral when an uncle asked our coauthor about our coauthor’s impression of the current President. Our coauthor’s immediate response was, “Do you really want me to answer that question?” Our coauthor knew that everyone else in the room would completely disagree, so our coauthor knew this was probably a can of worms that just didn’t need to be opened.

Second, we can change ourselves. Often, we are at fault and start conflicts. We may not even realize how our behavior caused the conflict until we take a step back and really analyze what is happening. When it comes to being at fault, it’s very important to admit that you’ve done wrong. Nothing is worse (and can stoke a conflict more) than when someone refuses to see their part in the conflict.

Third, we can attempt to change the other person. Let’s face it, changing someone else is easier said than done. Just ask your parents/guardians! All of our parents/guardians have attempted to change our behaviors at one point or another, and changing people is very hard. Even with the powers of punishment and reward, a lot of time change only lasts as long as the punishment or the reward. One of our coauthors was in a constant battle with our coauthors’ parents about thumb sucking as a child. Our coauthor’s parents tried everything to get the thumb sucking to stop. They finally came up with an ingenious plan. They agreed to buy a toy electric saw if their child didn’t engage in thumb sucking for the entire month. Well, for a whole month, no thumb sucking occurred at all. The child got the toy saw, and immediately inserted the thumb back into our coauthor’s mouth. This short story is a great illustration of the problems that can be posed by rewards. Punishment works the same way. As long as people are being punished, they will behave in a specific way. If that punishment is ever taken away, so will the behavior.

Lastly, we can just change the situation. Having a conflict with your roommates? Move out. Having a conflict with your boss? Find a new job. Having a conflict with a professor? Drop the course. Admittedly, changing the situation is not necessarily the first choice people should take when thinking about possibilities, but often it’s the best decision for long-term happiness. In essence, some conflicts will not be settled between people. When these conflicts arise, you can try and change yourself, hope the other person will change (they probably won’t, though), or just get out of it altogether.

Listen

The third step in the STLC model is listen. Humans are not always the best listeners. As we discussed in Chapter 7, listening is a skill. Unfortunately, during a conflict situation, this is a skill that is desperately needed and often forgotten. When we feel defensive during a conflict, our listening becomes spotty at best because we start to focus on ourselves and protecting ourselves instead of trying to be empathic and seeing the conflict through the other person’s eyes.

One mistake some people make is to think they’re listening, but in reality, they’re listening for flaws in the other person’s argument. We often use this type of selective listening as a way to devalue the other person’s stance. In essence, we will hear one small flaw with what the other person is saying and then use that flaw to demonstrate that obviously everything else must be wrong as well.

The goal of listening must be to suspend your judgment and really attempt to be present enough to accurately interpret the message being sent by the other person. When we listen in this highly empathic way, we are often able to see things from the other person’s point-of-view, which could help us come to a better-negotiated outcome in the long run.

Communicate

Lastly, but certainly not least, we communicate with the other person. Notice that Cahn and Abigail put communication as the last part of the STLC model because it’s the hardest one to do effectively during a conflict if the first three are not done correctly. When we communicate during a conflict, we must be hyper-aware of our nonverbal behavior (eye movement, gestures, posture, etc.). Nothing will kill a message faster than when it’s accompanied by bad nonverbal behavior. For example, rolling one’s eyes while another person is speaking is not an effective way to engage in conflict. One of our coauthors used to work with two women who clearly despised one another. They would never openly say something negative about the other person publicly, but in meetings, one would roll her eyes and make these non-word sounds of disagreement. The other one would just smile, slow her speech, and look in the other woman’s direction. Everyone around the conference table knew exactly what was transpiring, yet no words needed to be uttered at all.