Chapter 2: Overview of Interpersonal Communication

Cardi and Tilly have been friends since they were both in kindergarten. They are both applying to the same college, hoping to be roommates. However, Cardi gets accepted, but Tilly does not. Cardi is crushed because she wanted to share her college experience with her best friend. Tilly tells Cardi to go without her and she will try again next year after attending the local junior college for a semester. Cardi is not as excited to go to college anymore, because she is worried about Tilly. Cardi talks about different options with her parents, her other friends, and posts about it on social media. This idea of sharing our experiences, whether it be positive, or negative is interpersonal communication. When we offer information to other people and they offer information towards us, it is defined as interpersonal communication.

Interpersonal Communication can be informal (the checkout line) or formal (lecture classroom). Often, interpersonal communication occurs in face-to-face contexts. It is usually unplanned, spontaneous, and ungrammatical. Think about the conversations that you have with your friends and family. These are mainly interpersonal in nature. It is essential to learn about interpersonal communication because this is the type of communication that you will be doing for most of your life. At most colleges, public speaking is a required course. Yet, most people will not engage in making a public speech for the majority of their life, but they will communicate with one other person daily, which is interpersonal communication. Interpersonal communication can help us achieve our personal and professional goals. In this chapter, you will learn the concepts associated with interpersonal communication and how certain variables can help you achieve your goals.

In this chapter, you will learn about ways to make communication more effective. You will learn about communication models that might influence how a message is sent and/or received. You will also learn about characteristics that influence the message and can cause others not to accept or understand the message that you were trying to send.

2.1 Purposes of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Explain Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and its relationship to communication.

- Describe the relationship between self, others, and communication.

- Understand building and maintaining relationships.

Meeting Personal Needs

Communication fulfills our physical, personal, and social needs. Research has shown a powerful link between happiness and communication.1 In this particular study that included over 200 college students, they found that the ones who reported the highest levels of happiness also had a very active social life. The noted there were no differences between the happiest people and other similar peers in terms of how much they exercised, participated in religion, or engaged in other activities. The results from the study noted that having a social life can help people connect with others. We can connect with others through effective communication. Overall, communication is essential to our emotional wellbeing and perceptions about life.

Everyone has dreams that they want to achieve. What would happen if you never told anyone about your dreams? Would it really be possible to achieve your dreams without communication? To make your dreams a reality, you will have to interact with several people along the way who can help you fulfill your dreams and personal needs. The most famous people in history, who were actors, musicians, politicians, and business leaders, all started with a vision and were able to articulate those ideas to someone else who could help them launch their careers.

There are practical needs for communication. In every profession, excellent communication skills are a necessity. Doctors, nurses, and other health professionals need to be able to listen to their patients to understand their concerns and medical issues. In turn, these health professionals have to be able to communicate the right type of treatment and procedures so that their patients will feel confident that it is the best type of outcome, and they will comply with these medical orders.

Research has shown that couples who engage in effective communication report more happiness than couples who do not.2 Communication is not an easy skill for everyone. As you read further, you will see that there are a lot of considerations and variables that can affect how a message is relayed and received.

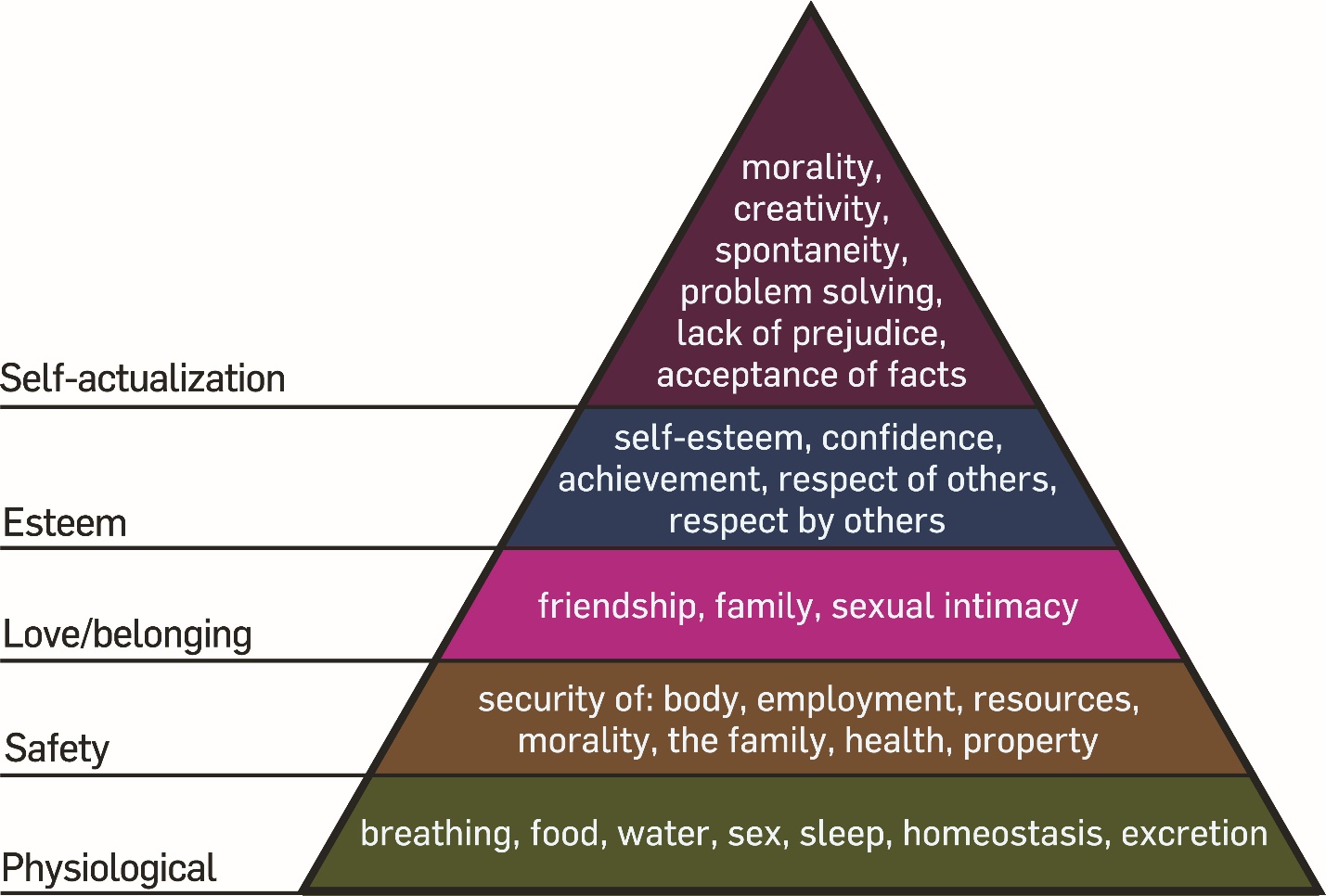

As the arrow in Figure 2.1 indicates, Maslow believed that human needs emerge in order starting from the bottom of the pyramid. At the basic level, humans must have physiological needs met, such as breathing, food, water, sex, homeostasis, sleep, and excretion. Once the physiological needs have been met, humans can attempt to meet safety needs, which include the safety of the body, family, resources, morality, health, and employment. A higher-order need that must be met is love and belonging, which encompasses friendship, sexual intimacy, and family. Another higher-order need that must be met before self-actualization is esteem, which includes self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect of others, and respect by others. Maslow argued that all of the lower needs were necessary to help us achieve psychological health and eventually self-actualization.3 Self-actualization leads to creativity, morality, spontaneity, problem-solving, lack of prejudice, and acceptance of facts.

Communicating and Meeting Personal Needs

As you will learn reading this chapter, it is important to understand people and know that people often communicate to satisfy their needs, but each person’s need level is different. To survive, physiological and safety needs must be met. Through communication, humans can work together to grow food, produce food, build shelter, create safe environments, and engage in protective behaviors. Once physiological and safety needs have been met, communication can then shift to love and belonging. Instead of focusing on living to see the next day, humans can focus on building relationships by discussing perhaps the value of a friendship or the desire for sexual intimacy. After creating a sense of love and belonging, humans can move forward to working on “esteem.” Communication may involve sharing praise, working toward goals, and discussion of strengths, which may lead to positive self-esteem. When esteem has been addressed and met, humans can achieve self-actualization. Communication will be about making life better, sharing innovative ideas, contributions to society, compassion and understanding, and providing insight to others. Imagine trying to communicate creatively about a novel or express compassion for others while starving and feeling unprotected. The problem of starving must be resolved before communication can shift to areas addressed within self-actualization.

Critics of Maslow’s theory argue that the hierarchy may not be absolute because it could be possible to achieve self-actualization without meeting the lower needs.4 For example, a parent/guardian might put before the needs of the child first if food is scarce. In this case, the need for food has not been fully met, and yet the parent/guardian is able to engage in self-actualized behavior. Other critics point out that Maslow’s hierarchy is rather Western-centric and focused on more individualistic cultures (focus is on the individual needs and desires) and not applicable to cultures that are collectivistic (focus is on the family, group, or culture’s needs and desires).5

It is important to understand needs because other people may have different needs. This can influence how a message is received. For instance, Shaun and Dee have been dating for some time. Dee wants to talk about wedding plans and the possibility of having children. However, Shaun is struggling to make ends meet. He is focused on his paycheck and where he will get money to cover his rent and what his next meal will be due to his tight income. It is very hard for Shaun to talk about their future together and future plans, when he is so focused on his basic physiological needs for food and water. Dee is on a different level, love and belonging, because she doesn’t have to worry about finances. Communicate can be difficult when two people have very drastic needs that are not being met. This can be frustrating to both Dee and Shaun. Dee feels like Shaun doesn’t love her because he refuses to talk about their future together. Shaun is upset with Dee, because she doesn’t seem to understand how hard it is for him to deal with such a tight budget. If we are not able to understand the other person’s needs, then we won’t be able to have meaningful conversations.

Learning About Self and Others

Communication is powerful, and sometimes words can affect us in ways that we might not imagine. Think back to a time when someone said something hurtful or insightful to you. How did it make you feel? Did you feel empowered to prove that person wrong or right? Even in a classroom, peers can say things that might make you reconsider how to feel about yourself.

Classmates provide a great deal of feedback to each other. They may comment on how well one particular student does, and this contributes to the student’s self-concept. The student might think, “People think I am a good student, so I must be.” When we interact with others, how they perceive and relate to us impacts our overall self-concept. According to Reńe M. Dailey,6 adolescents’ self-concepts were impacted by daily conversations when acceptance and challenges were present.

In high school, peers can be more influential than family members. Some peers can say very hurtful things and make you think poorly of yourself. And then, some peers believe in you and make you feel supported in your ideas. These interactions shape us in the person we are today.

Discovering Self-Concept – Who are you?

As a means to determine your self-concept, address the following questions, and ask others to answer the question about you.

Questions:

- Where did you grow up?

- What did you enjoy doing as a child?

- What qualities did others recognize in you as you grew up? (ex. “I know I can rely on you.” Or “You are good at making people laugh.”

- When you are with a group of people, what is your role in the group? (Ex. Listening, coordinating meeting times and location, initiating getting together).

Why do you think you communicate the way that you do? Is it based on some of the answers to these self-reflexive questions? Sometimes people behave and interact with others because of their past experiences, their background, and/or their observations with others.

On a job interview, if someone asks you to tell them about yourself, how would you describe yourself? The words that you use are related to your self-concept. Self-concept refers to the perceptions that you view about yourself. These perceptions are relatively stable. These might include your preferences, talents, emotional states, pet peeves, and beliefs.

Self-esteem is a part of self-concept. Self-esteem includes judgments of self-worth. A person can vary on high to low evaluations of self-esteem. People with high self-esteem will feel positive about themselves and others. They will mainly focus on their successes and believe that others’ comments are helpful.

On the other hand, people with low self-esteem will view things negatively and may focus more on their failures. They are more likely to take other people’s comments as criticism or hostility. A recent study found that people with low self-esteem prefer to communicate indirectly, such as an email or text, rather than face-to-face compared to people with high self-esteem.7

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Research indicates that your self-concept doesn’t happen when you are born.8 Rather, it happens over time. When you are very young, you are still learning about your body. Some children’s songs talk about your head, shoulders, and toes. As you develop into an adult, you learn more about yourself with others. It is through this communication with others that we not only learn about our self, but we can build and maintain relationships. To start a relationship with someone else, we might ask them very generic questions, such as their favorite color or favorite movie. Once we have established a connection, we might invite them to coffee or lunch. As we spend time with others, then we learn more about them by talking with them, and then we discover our likes and dislikes with someone. It is through this sharing of information with others that we learn more about them. We can build intimacy and a deeper connection with others when they tell us more about their experiences and their perspectives.

Think about all the relationships that you have developed over time. Now think about how these people either shaped your self-concept or perceptions regarding your self-esteem. For instance, you may have had a coach or teacher that impacted the way that you learn about a certain topic. You may have had an inspirational teacher that helped you find your career path or you might have had a coach that constantly embarrassed you in front of your teammates by yelling at you. These two very different experiences can impact how you feel about yourself.

We are constantly receiving messages from people throughout our life. On social media, there will be people who like our posts, but there might be some who disagree or not like what we post. These experiences can help us understand what we value and what things we may choose to ignore.

From an early age, we might compare ourselves to others. This is called social comparison. For instance, in grade school, your teacher might have asked everyone to line up against the wall to see who is the tallest and who is the shortest. Instinctively, we already compare ourselves to others. When there is an exam, students want to know how other people performed on the exam to see if they are different or similar. By comparing ourselves to others, we might be able to discern if we are better or worse than others, which can, in turn, influence our self-esteem.

We will build and maintain relationships with others who have similar self-concepts to us, or we perceive them to have a similar self-concept about ourselves. Your closest friends are usually people that are similar to you in some way. These relationships most likely occurred because you were willing to disclose information about yourself to see if you were similar or compatible with the other person.

Uncertainty Reduction Theory

As humans habitually form relationships, theorists Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese9 sought to understand how humans begin relationships. Their research focused on the initiation of relationships, and it was observed that humans, in first meetings, attempt to reduce uncertainty. Thus, the Uncertainty Reduction theory emerged. This theory addressed cognitive uncertainty (uncertainty associated with the beliefs and attitudes of another) and behavioral uncertainty (uncertainty regarding how another person might behave). Three strategies are used to reduce uncertainty, including passive, active, and interactive strategies. Passive strategies avoid disrupting the other individual and can be accomplished through observation. Active strategies involve asking a friend for information or observing social networking such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Finally, interactive strategies involve direct contact with the other individual.

Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese (1975) believed that when we meet new people, we are fraught with uncertainty about the new relationship and will seek to reduce this uncertainty and its resulting anxiety.10 They found that the best and most common way of reducing this uncertainty is through self-disclosure. As such, self-disclosure needs to be reciprocal to successfully reduce uncertainty. Upon new introductions, we tend to consider three things: (1) The person’s ability to reward or punish us, (2) the degree to which they meet or violate our social expectations, and (3) whether we expect to reencounter them. Most of these considerations are made instantly and often through expectancy biases. Research revealed that we tend to make snap decisions about people upon meeting them based on previously held beliefs and experiences and that these decisions are extremely difficult to overcome or change.11 When we meet other people, there is a ton of information for us to go through very quickly, so just as in other situations, we draw on our previous understandings and experiences to make assumptions about this new person. The process of self-disclosure allows us to gain more data to create a more accurate understanding of other individuals, which gives us better insight into their future actions and reduces our uncertainty of them.

These ideas can be seen very clearly in the digital age as they relate to Chang, Fang, and Huang’s (2015) research on consumer reviews online and their effect on potential purchasers.12 They found that similarities in a reviewer’s diction to the shoppers’ language, and the confirmation of the shoppers’ prior beliefs, created more credibility. We are more comfortable with things and people that are like us, and that we understand and can predict. How does this translate to more personal forms of computer-mediated communication (CMC) such as email?

In another study, researchers sought to find out what factors influence our understanding of such messages.13 They found that the individual personality of the receiver was the biggest factor in the way the messages were interpreted. Again we see that we as humans interpret data in as much as we are familiar with that data. We will consistently make assumptions based on what we would do or have experienced previously. The lack of nonverbal information in CMC adds to this. We have very little more than text to use in the formation of our opinions and seek to eliminate the uncertainty.

We need to go back then to the solution that Berger and Calabrese found for the reduction of uncertainty, self-disclosure. Many new relationships today, particularly in the dating world, begin online. To be successful in these initial encounters, the key would seem to be to engage in as much self-disclosure as possible on the front end to help others reduce anxiety based on uncertainty. More research in this area would support that an increase in self-disclosure results in an increase in positive reactions from similar users in a social network. The implied problem of all of this is that there is little to no way to verify the information disclosed by users. So a new kind of uncertainty reduction theory seems necessary. How can we alter our previous notions of human behavior to reflect a culture in which deception is presumably so much easier? Is the answer to live in a world of uncertainty and its resulting anxiety? To what degree must we assume the best of others and engage in potentially risky relationships to maintain a functional society? Who can we trust, and how can we know?

Key Takeaways

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs impacts the content of communication as well as the purpose.

- The feedback we receive from others provides insight into who we are as individuals.

- A major theory in building relationships is Uncertainty Reduction Theory, which explains how we put ourselves at ease with others.

Exercises

- Write down a list of questions you asked when you first met your college roommate or a new friend? Review these questions and write down why these questions are useful to you.

- Recall a situation in which you were recently carrying on a conversation with another person. Write down the details of the conversation. Now, relate the parts of the conversation to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

2.2 Elements of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Understand that communication is a process.

- Differentiate among the components of communication processes and communication models.

- Describe the differences between the sender and receiver of a message.

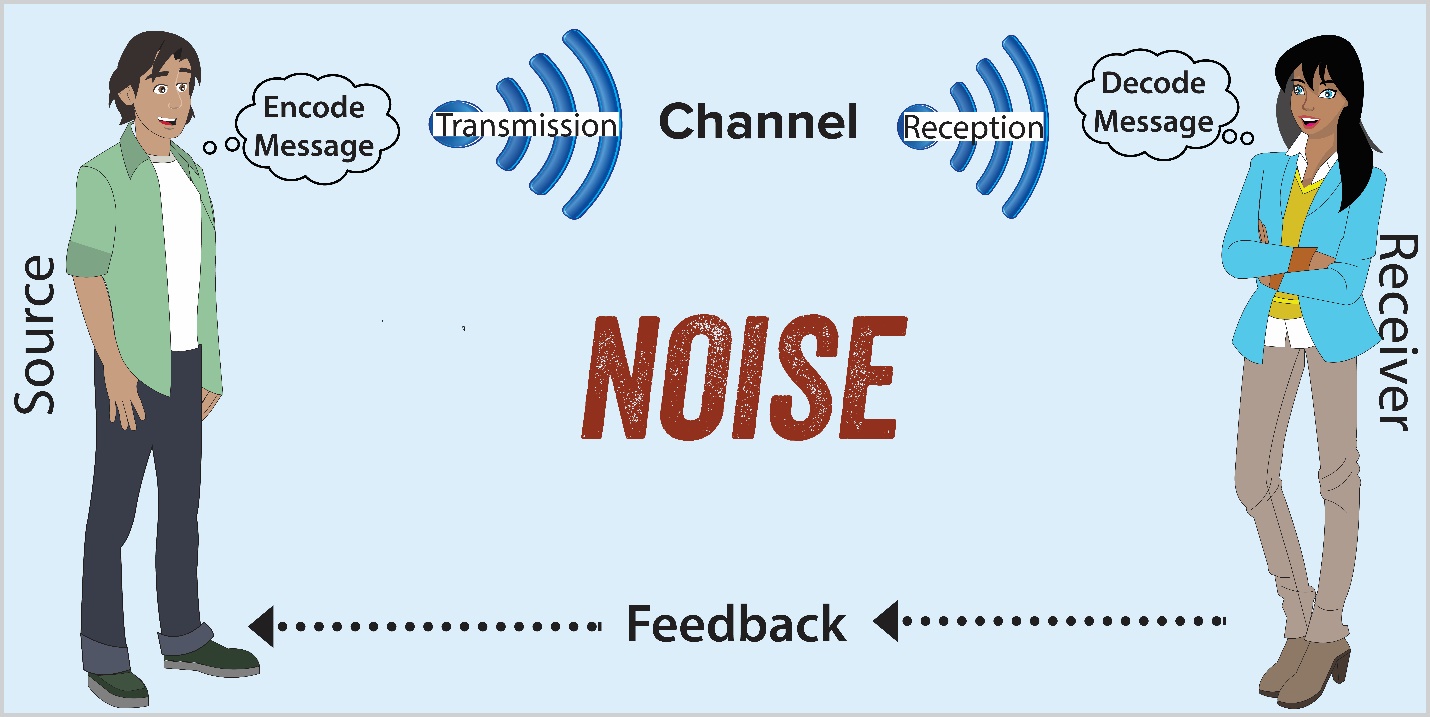

You may think that communication is easy. However, at moments in your life, communication might be hard and difficult to understand. We can study communication similar to the way we study other systems. There are elements to the communication process that are important to understand. Each interaction that we have will typically include a sender, receiver, message, channel, feedback, and noise. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Sender

Humans encode messages naturally, and we don’t often consider this part of the process. However, if you have ever thought about the exact words that you would use to get a later curfew from your parents/guardians and how you might refute any counterpoints, then you intuitively know that choosing the right words – “encoding” – weighed heavily in your ability to influence your parents/guardians successfully. The language you chose mattered.

The sender is the encoder or source of the message. The sender is the person who decides to communicate and the intent of the message. The source may decide to send messages to entertain, persuade, inform, include, or escape. Often, the sources will create a message based on their feelings, thoughts, perceptions, and past experiences. For instance, if you have feelings of affection towards someone but never communicate those feelings toward that person, they will never know. The sender can withhold or release information.

Receiver

The transactional model of communication teaches us that we are both the sender and receiver simultaneously. The receiver(s) is the individual who decodes the message and tries to understand the source of the message. Receivers have to filter messages based on their attitudes, beliefs, opinions, values, history, and prejudices. People will encode messages through their five senses. We have to pay attention to the source of the message to receive the message. If the receiver does not get the message, then communication did not occur. The receiver needs to obtain a message.

Daily, you will receive several messages. Some of these messages are intentional. And some of these messages will be unintentional. For instance, a person waving in your direction might be waving to someone behind you, but you accidentally think they are waving at you. Some messages will be easy to understand, and some messages will be hard to interpret. Every time a person sends a message, they are also receiving messages simultaneously.

Message

Messages include any type of textual, verbal, and nonverbal aspects of communication, in which individuals give meaning. People send messages intentionally (texting a friend to meet for coffee) or unintentionally (accidentally falling asleep during lectures). Messages can be verbal (saying hello to your parents/guardians), nonverbal (hugging your parents/guardians), or text (words on a computer screen). Essentially, communication is how messages create meaning. Yet, meanings differ among people. For instance, a friend of yours promises to repay you for the money they borrowed, and they say “sorry” for not having any money to give you. You might think they were insincere, but another person might think that it was a genuine apology. People can vary in their interpretations of messages.

Channel

With advances in technology, cell phones act as many different channels of communication at once. Consider that smartphones allow us to talk and text. Also, we can receive communication through Facebook, Twitter, Email, Instagram, Snapchat, Reddit, and Vox. All of these channels are in addition to our traditional channels, which were face-to-face communication, letter writing, telegram, and the telephone. The addition of these new communication channels has changed our lives forever. The channel is the medium in which we communicate our message. Think about breaking up a romantic relationship. Would you rather do it via face-to-face or via a text message? Why did you answer the way that you did? The channel can impact the message.

Now, think about how you hear important news. Do you learn about it from the Internet, social media, television, newspaper, or others? The channel is the medium in which you learn about information.

It may seem like a silly thing to talk about channels, but a channel can make an impact on how people receive the message. For instance, a true story tells about a professional athlete who proposed marriage to his girlfriend by sending her the ring through the postal mail service. He sent her a ring and a recorded message asking her to marry him. She declined his proposal and refused to return the ring.14 In this case, the channel might have been better if he asked her face-to-face.

Just be mindful of how the channel can affect the way that a receiver reacts and responds to your message. For instance, a handwritten love letter might be more romantic than a typed email. On the other hand, if there was some tragic news about your family, you would probably want someone to call you immediately rather than sending you a letter.

Overall, people naturally know that the message impacts which channel they might use. In a research study focused on channels, college students were asked about the best channels for delivering messages.15 College students said that they would communicate face-to-face if the message was positive, but use mediated channels if the message was negative.

Feedback

Feedback is the response to the message. If there is no feedback, communication would not be effective. Feedback is important because the sender needs to know if the receiver got the message. Simultaneously, the receiver usually will give the sender some sort of message that they comprehend what has been said. If there is no feedback or if it seems that the receiver did not understand the message, then it is negative feedback. However, if the receiver understood the message, then it is positive feedback. Positive feedback does not mean that the receiver entirely agrees with the sender of the message, but rather the message was comprehended. Sometimes feedback is not positive or negative; it can be ambiguous. Examples of ambiguous feedback might include saying “hmmm” or “interesting.” Based on these responses, it is not clear if the receiver of the message understood part or the entire message. It is important to note that feedback doesn’t have to come from other people. Sometimes, we can be critical of our own words when we write them in a text or say them out loud. We might correct our words and change how we communicate based on our internal feedback.

Environment

The context or situation where communication occurs and affects the experience is referred to as the environment. We know that the way you communicate in a professional context might be different than in a personal context. In other words, you probably won’t talk to your boss the same way you would talk to your best friend. (An exception might be if your best friend was also your boss). The environment will affect how you communicate. For instance, in a library, you might talk more quietly than normal so that you don’t disturb other library patrons. However, in a nightclub or bar, you might speak louder than normal due to the other people talking, music, or noise. Hence, the environment makes a difference in the way in which you communicate with others.

It is also important to note that environments can be related to fields of experience or a person’s past experiences or background. For instance, a town hall meeting that plans to cut primary access to lower socioeconomic residents might be perceived differently by individuals who use these services and those who do not. Environments might overlap, but sometimes they do not. Some people in college have had many family members who attended the same school, but other people do not have any family members that ever attended college.

Noise

Anything that interferes with the message is called noise. Noise keeps the message from being completely understood by the receiver. If noise is absent, then the message would be accurate. However, usually, noise impacts the message in some way. Noise might be physical (e.g., television, cell phone, fan, etc.), or it might be psychological (e.g., thinking about your parents/guardians or missing someone you love). Noise is anything that hinders or distorts the message.

There are four types of noise. The first type is physical noise. This is noise that comes from a physical object. For instance, people talking, birds chirping, a jackhammer pounding concrete, a car revving by, are all different types of physical noise.

The second type of noise is psychological noise. This is the noise that no one else can see unless you are a mind reader. It is the noise that occurs in a person’s mind, such as frustration, anger, happiness, or depression. When you talk to a person, they might act and behave like nothing is wrong, but deep inside their mind, they might be dealing with a lot of other issues or problems. Hence, psychological noise is difficult to see or understand because it happens in the other person’s mind.

The third type of noise is semantic noise, which deals with language. This could refer to jargon, accents, or language use. Sometimes our messages are not understood by others because of the word choice. For instance, if a person used the word “lit,” it would probably depend on the other words accompanying the word “lit” and or the context. To say that “this party is lit” would mean something different compared to “he lit a cigarette.” If you were coming from another country, that word might mean something different. Hence, sometimes language-related problems, where the receiver can’t understand the message, are referred to as semantic noise.

The fourth and last type of noise is called physiological noise. This type of noise is because the receiver’s body interferes or hinders the acceptance of a message. For instance, if the person is blind, they are unable to see any written messages that you might send. If the person is deaf, then they are unable to hear any spoken messages. If the person is very hungry, then they might pay more attention to their hunger than any other message.

Mindfulness Activity

We live in a world where there is constant noise. Practice being mindful of sound. Find a secluded spot and just close your eyes. Focus on the sounds around you. Do you notice certain sounds more than others? Why? Is it because you place more importance on those sounds compared to other sounds?

We live in a world where there is constant noise. Practice being mindful of sound. Find a secluded spot and just close your eyes. Focus on the sounds around you. Do you notice certain sounds more than others? Why? Is it because you place more importance on those sounds compared to other sounds?

Sounds can be helpful to your application of mindfulness.16 Some people prefer paying attention to sounds rather than their breath when meditating. The purpose of this activity is to see if you can discern some sounds more than others. Some people might find these sounds noisy and very distracting. Others might find the sounds calming and relaxing.

If you watch old episodes of Superman, you might see scenes where he has to concentrate on hearing the sounds of someone calling for help. Superman can filter all the other sounds in the world to figure out where he needs to focus his attention.

There will be many times in life where you will be distracted because you might be overwhelmed with all the noise. It is essential to take a few minutes, just to be mindful of the noise and how you can deal with all the distractions. Once you are aware of the things that trigger these distractions or noise, then you will be able to be more focused and to be a better communicator.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is a process because senders and receivers act as senders and receivers simultaneously, with the receiver’s feedback serving as a key element to continuing the process.

- The components of the communication process involve the source, sender, channel, message, environment, and noise.

Exercises

- Think of your most recent communication with another individual. Write down this conversation and, within the conversation, identify the components of the communication process.

- Think about the different types of noise that affect communication. Can you list some examples of how noise can make communication worse?

- Think about the advantages and disadvantages of different channels. Write down the pros and cons of the different channels of communication.

2.3 Perception Process

Learning Objectives

- Describe perception and aspects of interpersonal perception.

- List and explain the three stages of the perception process.

- Understand the relationship between interpersonal communication and perception.

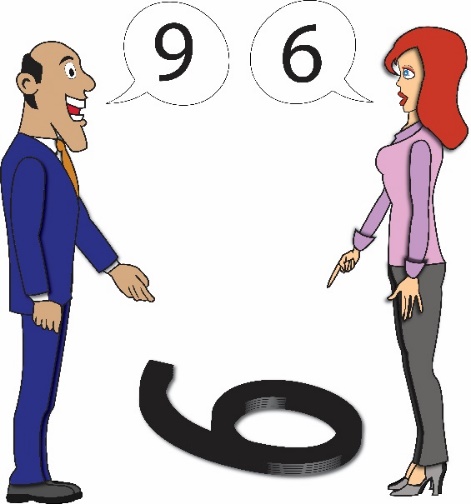

As you can see from the picture, how you view something is also how you will describe and define it. Your perception of something will determine how you feel about it and how you will communicate about it. In the picture above, do you see it as a six or a nine? Why did you answer the way that you did?

Your perceptions affect who you are, and they are based on your experiences and preferences. If you have a horrible experience with a restaurant, you probably won’t go to that restaurant in the future. You might even tell others not to go to that restaurant based on your personal experience. Thus, it is crucial to understand how perceptions can influence others.

Sometimes the silliest arguments occur with others because we don’t understand their perceptions of things. Just like the illustration shows, it is important to make sure that you see things the same way that the other person does. In other words, put yourself in their shoes and see it from their perspective before jumping to conclusions or getting upset. That person might have a legitimate reason why they are not willing to concede with you.

Perception

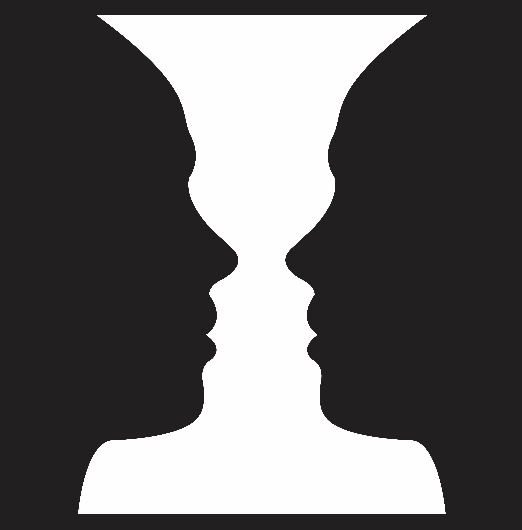

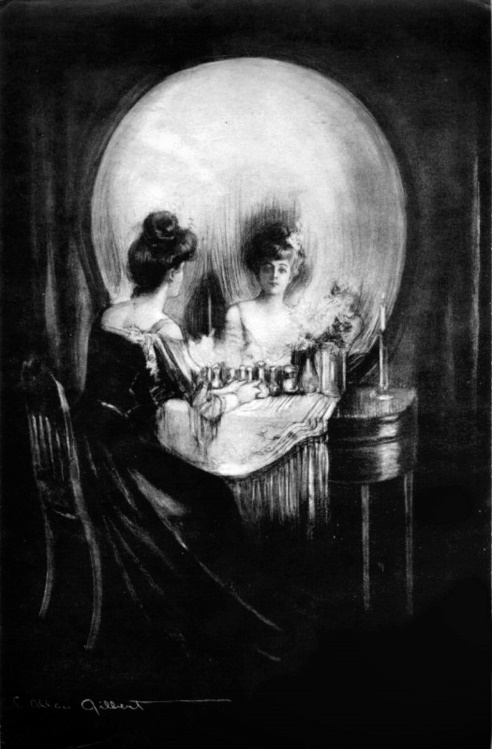

Many of our problems in the world occur due to perception, or the process of acquiring, interpreting, and organizing information that comes in through your five senses. When we don’t get all the facts, it is hard to make a concrete decision. We have to rely on our perceptions to understand the situation. In this section, you will learn tools that can help you understand perceptions and improve your communication skills. As you will see in many of the illustrations on perception, people can see different things. In some of the pictures, some might only be able to see one picture, but there might be others who can see both images, and a small amount might be able to see something completely different from the rest of the class.

Many famous artists over the years have played with people’s perceptions. Figure 2.3 is an example of three artists’ use of twisted perceptions. The first picture was initially created by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin and is commonly called The Rubin Vase. Essentially, you have what appears to either be a vase (the white part) or two people looking at each other (the black part). This simple image is both two images and neither image at the same time. The second work of art is Charles Allan Gilbert’s (1892) painting “All is Vanity.” In this painting, you can see a woman sitting staring at herself in the mirror. At the same time, the image is also a giant skull. Lastly, we have William Ely Hill (1915) “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law,” which may have been loosely based on an 1888 German postcard. In Hill’s painting, you have two different images, one of a young woman and one of an older woman. The painting was initially published in an American humor magazine called Puck. The caption “They are both in this picture — Find them” ran alongside the picture. These visual images are helpful reminders that we don’t always perceive things in the same way as those around us. There are often multiple ways to view and understand the same set of events.

When it comes to interpersonal communication, each time you talk to other people, you present a side of yourself. Sometimes this presentation is a true representation of yourself, and other times it may be a fake version of yourself. People present themselves how they want others to see them. Some people present themselves positively on social media, and they have wonderful relationships. Then, their followers or fans get shocked to learn when those images are not true to what is presented. If we only see one side of things, we might be surprised to learn that things are different. In this section, we will learn that the perception process has three stages: attending, organizing, and interpreting.

Attending

The first step of the perception process is to select what information you want to pay attention to or focus on, which is called attending. You will pay attention to things based on how they look, feel, smell, touch, and taste. At every moment, you are obtaining a large amount of information. So, how do you decide what you want to pay attention to and what you choose to ignore? People will tend to pay attention to things that matter to them. Usually, we pay attention to things that are louder, larger, different, and more complex to what we ordinarily view.

When we focus on a particular thing and ignore other elements, we call it selective perception. For instance, when you are in love, you might pay attention to only that special someone and not notice anything else. The same thing happens when we end a relationship, and we are devasted, we might see how everyone else is in a great relationship, but we aren’t.

There are a couple of reasons why you pay attention to certain things more so than others.

The first reason why we pay attention to something is because it is extreme or intense. In other words, it stands out of the crowd and captures our attention, like an extremely good looking person at a party or a big neon sign in a dark, isolated town. We can’t help but notice these things because they are exceptional or extraordinary in some way.

Second, we will pay attention to things that are different or contradicting. Commonly, when people enter an elevator, they face the doors. Imagine if someone entered the elevator and stood with their back to the elevator doors staring at you. You might pay attention to this person more than others because the behavior is unusual. It is something that you don’t expect, and that makes it stand out more to you. On another note, different could also be something that you are not used to or something that no longer exists for you. For instance, if you had someone very close to you pass away, then you might pay more attention to the loss of that person than to anything else. Some people grieve for an extended period because they were so used to having that person around, and things can be different since you don’t have them to rely on or ask for input.

The third thing that we pay attention to is something that repeats over and over again. Think of a catchy song or a commercial that continually repeats itself. We might be more alert to it since it repeats, compared to something that was only said once.

The fourth thing that we will pay attention to is based on our motives. If we have a motive to find a romantic partner, we might be more perceptive to other attractive people than normal, because we are looking for romantic interests. Another motive might be to lose weight, and you might pay more attention to exercise advertisements and food selection choices compared to someone who doesn’t have the motive to lose weight. Our motives influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore.

The last thing that influences our selection process is our emotional state. If we are in an angry mood, then we might be more attentive to things that get us angrier. As opposed to, if we are in a happy mood, then we will be more likely to overlook a lot of negativity because we are already happy. Selecting doesn’t involve just paying attention to certain cues. It also means that you might be overlooking other things. For instance, people in love will think their partner is amazing and will overlook a lot of their flaws. This is normal behavior. We are so focused on how wonderful they are that we often will neglect the other negative aspects of their behavior.

Organizing

Look again at the three images in Figure 2.3. What were the first things that you saw when you looked at each picture? Could you see the two different images? Which image was more prominent? When we examine a picture or image, we engage in organizing it in our head to make sense of it and define it. This is an example of organization. After we select the information that we are paying attention to, we have to make sense of it in our brains. This stage of the perception process is referred to as organization. We must understand that the information can be organized in different ways. After we attend to something, our brains quickly want to make sense of this data. We quickly want to understand the information that we are exposed to and organize it in a way that makes sense to us.

There are four types of schemes that people use to organize perceptions.17 First, physical constructs are used to classify people (e.g., young/old; tall/short; big/small). Second, role constructs are social positions (e.g., mother, friend, lover, doctor, teacher). Third, interaction constructs are the social behaviors displayed in the interaction (e.g., aggressive, friendly, dismissive, indifferent). Fourth, psychological constructs are the dispositions, emotions, and internal states of mind of the communicators (e.g., depressed, confident, happy, insecure). We often use these schemes to better understand and organize the information that we have received. We use these schemes to generalize others and to classify information.

Let’s pretend that you came to class and noticed that one of your classmates was wildly waving their arms in the air at you. This will most likely catch your attention because you find this behavior strange. Then, you will try to organize or makes sense of what is happening. Once you have organized it in your brain, you will need to interpret the behavior.

Interpreting

The final stage of the perception process is interpreting. In this stage of perception, you are attaching meaning to understand the data. So, after you select information and organize things in your brain, you have to interpret the situation. As previously discussed in the above example, your friend waves their hands wildly (attending), and you are trying to figure out what they are communicating to you (organizing). You will attach meaning (interpreting). Does your friend need help and is trying to get your attention, or does your friend want you to watch out for something behind you?

We interpret other people’s behavior daily. Walking to class, you might see an attractive stranger smiling at you. You could interpret this as a flirtatious behavior or someone just trying to be friendly. Scholars have identified some factors that influence our interpretations:18

Personal Experience

First, personal experience impacts our interpretation of events. What prior experiences have you had that affect your perceptions? Maybe you heard from your friends that a particular restaurant was really good, but when you went there, you had a horrible experience, and you decided you never wanted to go there again. Even though your friends might try to persuade you to try it again, you might be inclined not to go, because your past experience with that restaurant was not good.

Another example might be a traumatic relationship break up. You might have had a relational partner that cheated on you and left you with trust issues. You might find another romantic interest, but in the back of your mind, you might be cautious and interpret loving behaviors differently, because you don’t want to be hurt again.

Involvement

Second, the degree of involvement impacts your interpretation. The more involved or deeper your relationship is with another person, the more likely you will interpret their behaviors differently compared to someone you do not know well. For instance, let’s pretend that you are a manager, and two of your employees come to work late. One worker just happens to be your best friend and the other person is someone who just started and you do not know them well. You are more likely to interpret your best friend’s behavior more altruistically than the other worker because you have known your best friend for a longer period. Besides, since this person is your best friend, this implies that you interact and are more involved with them compared to other friends.

Expectations

Third, the expectations that we hold can impact the way we make sense of other people’s behaviors. For instance, if you overheard some friends talking about a mean professor and how hostile they are in class, you might be expecting this to be true. Let’s say you meet the professor and attend their class; you might still have certain expectations about them based on what you heard. Even those expectations might be completely false, and you might still be expecting those allegations to be true.

Assumptions

Fourth, there are assumptions about human behavior. Imagine if you are a personal fitness trainer, do you believe that people like to exercise or need to exercise? Your answer to that question might be based on your assumptions. If you are a person who is inclined to exercise, then you might think that all people like to work out. However, if you do not like to exercise but know that people should be physically fit, then you would more likely agree with the statement that people need to exercise. Your assumptions about humans can shape the way that you interpret their behavior. Another example might be that if you believe that most people would donate to a worthy cause, you might be shocked to learn that not everyone thinks this way. When we assume that all humans should act a certain way, we are more likely to interpret their behavior differently if they do not respond in a certain way.

Relational Satisfaction

Fifth, relational satisfaction will make you see things very differently. Relational satisfaction is how satisfied or happy you are with your current relationship. If you are content, then you are more likely to view all your partner’s behaviors as thoughtful and kind. However, if you are not satisfied in your relationship, then you are more likely to view their behavior has distrustful or insincere. Research has shown that unhappy couples are more likely to blame their partners when things go wrong compared to happy couples.19

Conclusion

In this section, we have discussed the three stages of perception: attending, organizing, and interpreting. Each of these stages can occur out of sequence. For example, if your parent/guardian had a bad experience at a car dealership based on their interpretation (such as “They overcharged me for the car and they added all these hidden fees.”), then it can influence their future selection (looking for credible and highly rated car dealerships, and then your parent/guardian can organize the information (car dealers are just trying to make money, the assumption is that they think most customers don’t know a lot about cars). Perception is a continuous process, and it is very hard to determine the start and finish of any perceptual differences.

Key Takeaways

- Perception involves attending, organizing, and interpreting.

- Perception impacts communication.

- Attending, organizing, and interpreting have specific definitions, and each is impacted by multiple variables.

Exercises

- Take a walk to a place you usually go to on campus or in your neighborhood. Before taking your walk, mentally list everything that you will see on your walk. As you walk, notice everything on your path. What new things do you notice now that you are deliberately “attending” to your environment?

- What affects your perception? Think about where you come from and your self-concept. How do these two factors impact how you see the world?

- Look back at a previous text or email that you got from a friend. After reading it, do you have a different interpretation of it now compared to when you first got it? Why? Think about how interpretation can impact communication if you didn’t know this person. How does it differ?

2.4 Models of Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among and describe the various action models of interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate among and describe the various interactional models of interpersonal communication.

- Differentiate among and describe the various transactional models of interpersonal communication.

In the world of communication, we have several different models to help us understand what communication is and how it works. A model is a simplified representation of a system (often graphic) that highlights the crucial components and connections of concepts, which are used to help people understand an aspect of the real-world. For our purposes, the models have all been created to help us understand how real-world communication interactions occur. The goal of creating models is three-fold:

- to facilitate understanding by eliminating unnecessary components,

- to aid in decision making by simulating “what if” scenarios, and

- to explain, control, and predict events on the basis of past observations.20

Over the next few paragraphs, we’re going to examine three different types of models that communication scholars have proposed to help us understand interpersonal interactions: action, interactional, and transactional.

Action Models

In this section, we will be discussing different models to understand interpersonal communication. The purpose of using models is to provide visual representations of interpersonal communication and to offer a better understanding of how various scholars have conceptualized it over time. The first type of model we’ll be exploring are action models, or communication models that view communication as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver.

Shannon-Weaver Model

Shannon and Weaver were both engineers for the Bell Telephone Labs. Their job was to make sure that all the telephone cables and radio waves were operating at full capacity. They developed the Shannon-Weaver model, which is also known as the linear communication model (Weaver & Shannon, 1963).21 As indicated by its name, the scholars believed that communication occurred in a linear fashion, where a sender encodes a message through a channel to a receiver, who will decode the message. Feedback is not immediate. Examples of linear communication were newspapers, radio, and television.

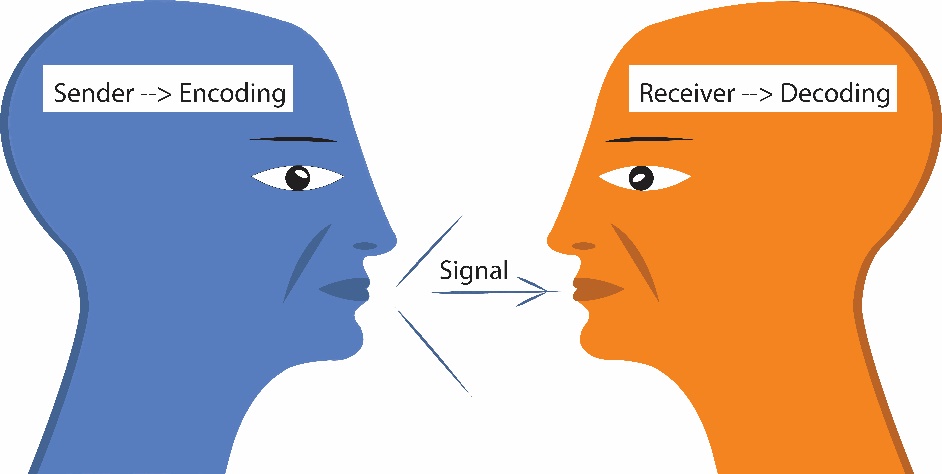

Early Schramm Model

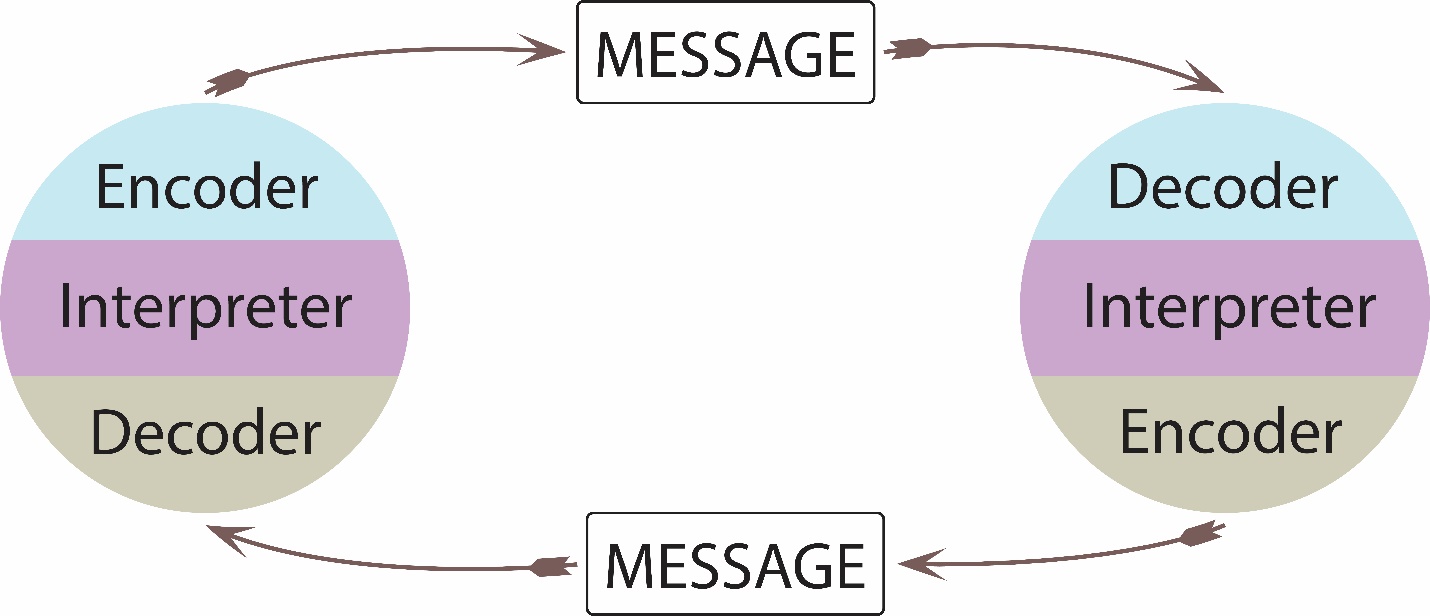

The Shannon-Weaver model was criticized because it assumed that communication always occurred linearly. Wilbur Schram (1954) felt that it was important to notice the impact of messages.22 Schramm’s model regards communication as a process between an encoder and a decoder. Most importantly, this model accounts for how people interpret the message. Schramm argued that a person’s background, experience, and knowledge are factors that impact interpretation. Besides, Schramm believed that the messages are transmitted through a medium. Also, the decoder will be able to send feedback about the message to indicate that the message has been received. He argued that communication is incomplete unless there is feedback from the receiver. According to Schramm’s model, encoding and decoding are vital to effective communication. Any communication where decoding does not occur or feedback does not happen is not effective or complete.

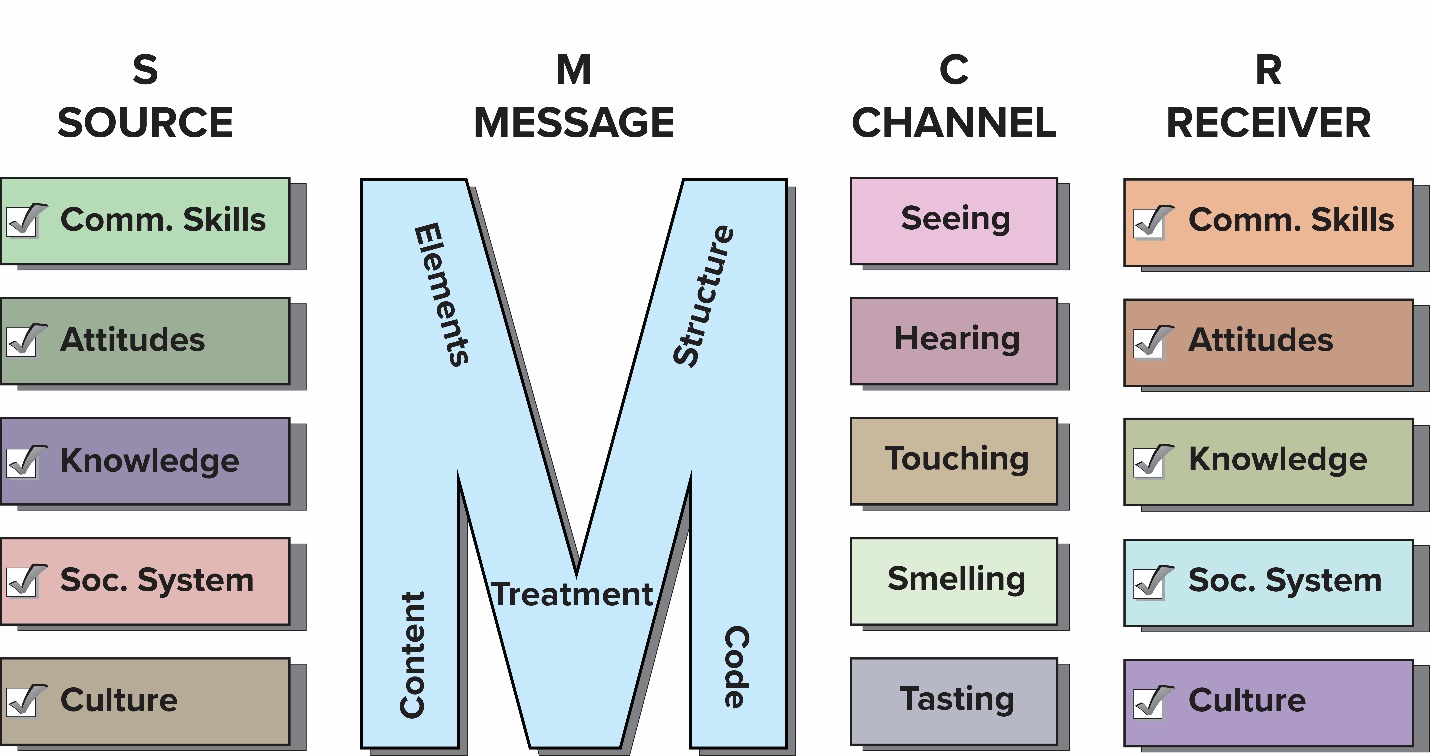

Berlo’s SMCR Model

David K. Berlo (1960)23 created the SMCR model of communication. SMCR stands for sender, message, channel, receiver. Berlo’s model describes different components of the communication process. He argued that there are three main parts of all communication, which is the speaker, the subject, and the listener. He maintained that the listener determines the meaning of any message.

In regards to the source or sender of the message, Berlo identified factors that influence the source of the message. First, communication skills refer to the ability to speak or write. Second, attitude is the person’s point-of-view, which may be influenced by the listener. The third is whether the source has requisite knowledge on a given topic to be effective. Fourth, social systems include the source’s values, beliefs, and opinions, which may influence the message.

Next, we move onto the message portion of the model. The message can be sent in a variety of ways, such as text, video, speech. At the same time, there might be components that influence the message, such as content, which is the information being sent. Elements refer to the verbal and nonverbal behaviors of how the message is sent. Treatment refers to how the message was presented. The structure is how the message was organized. Code is the form in which the message was sent, such as text, gesture, or music.

The channel of the message relies on the basic five senses of sound, sight, touch, smell, and taste. Think of how your mother might express her love for you. She might hug you (touch) and say, “I love you” (sound), or make you your favorite dessert (taste). Each of these channels is a way to display affection.

The receiver is the person who decodes the message. Similar to the models discussed earlier, the receiver is at the end. However, Berlo argued that for the receiver to understand and comprehend the message, there must be similar factors to the sender. Hence, the source and the receiver have similar components. In the end, the receiver will have to decode the message and determine its meaning. Berlo tries to present the model of communication as simple as possible. His model accounts for variables that will obstruct the interpretation of the model.

Interaction Models

In this section, we’re going to explore the next evolution of communication models, interaction models. Interaction models view the sender and the receiver as responsible for the effectiveness of the communication. One of the biggest differences between the action and interaction models is a heightened focus on feedback.

Osgood and Schramm Model

Osgood-Schramm’s model of communication is known as a circular model because it indicates that messages can go in two directions.24 Hence, once a person decodes a message, then they can encode it and send a message back to the sender. They could continue encoding and decoding into a continuous cycle. This revised model indicates that: 1) communication is not linear, but circular; 2) communication is reciprocal and equal; 3) messages are based on interpretation; 4) communication involves encoding, decoding, and interpreting. The benefit of this model is that the model illustrates that feedback is cyclical. It also shows that communication is complex because it accounts for interpretation. This model also showcases the fact that we are active communicators, and we are active in interpreting the messages that we receive.

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model

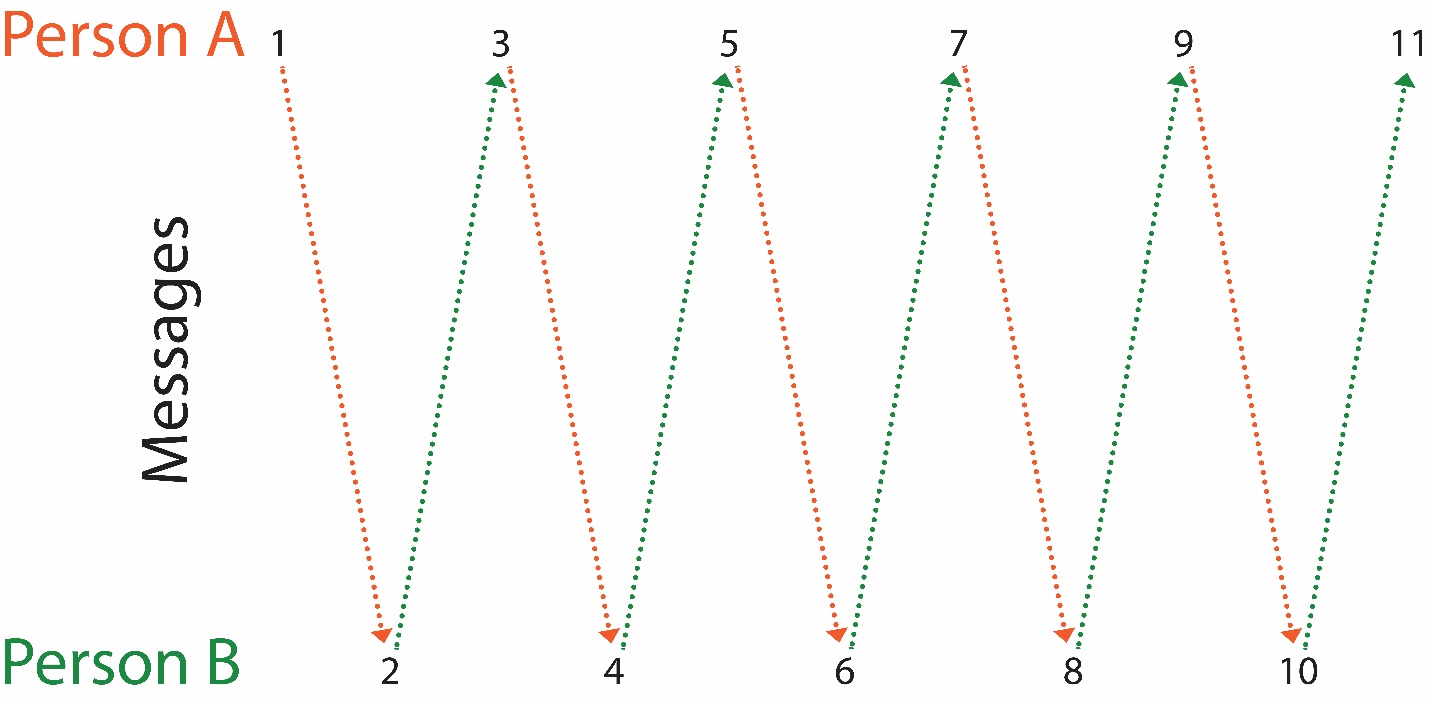

Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson argued that communication is continuous.25 The researchers argued that communication happens all the time. Every time a message is sent, then a message is returned, and it continues from Person A to Person B until someone stops. Feedback is provided every time that Person A sends a message. With this model, there are five axioms.

First, one cannot, not communicate. This means that everything one does has communicative value. Even if people do not talk to each other, then it still communicates the idea that both parties do not want to talk to each other. The second axiom states that every message has a content and relationship dimension. Content is the informational part of the message or the subject of discussion. The relationship dimension refers to how the two communicators feel about each other. The third axiom is how the communicators in the system punctuate their communicative sequence. The scholars observed that every communication event has a stimulus, response, and reinforcement. Each communicator can be a stimulus or a response. Fourth, communication can be analog or digital. Digital refers to what the words mean. Analogical is how the words are said or the nonverbal behavior that accompanies the message. The last axiom states that communication can be either symmetrical or complementary. This means that both communicators have similar power relations, or they do not. Conflict and misunderstandings can occur if the communicators have different power relations. For instance, your boss might have the right to fire you from your job if you do not professionally conduct yourself.

Transaction Models

The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. Basically, sending and receiving messages happen simultaneously.

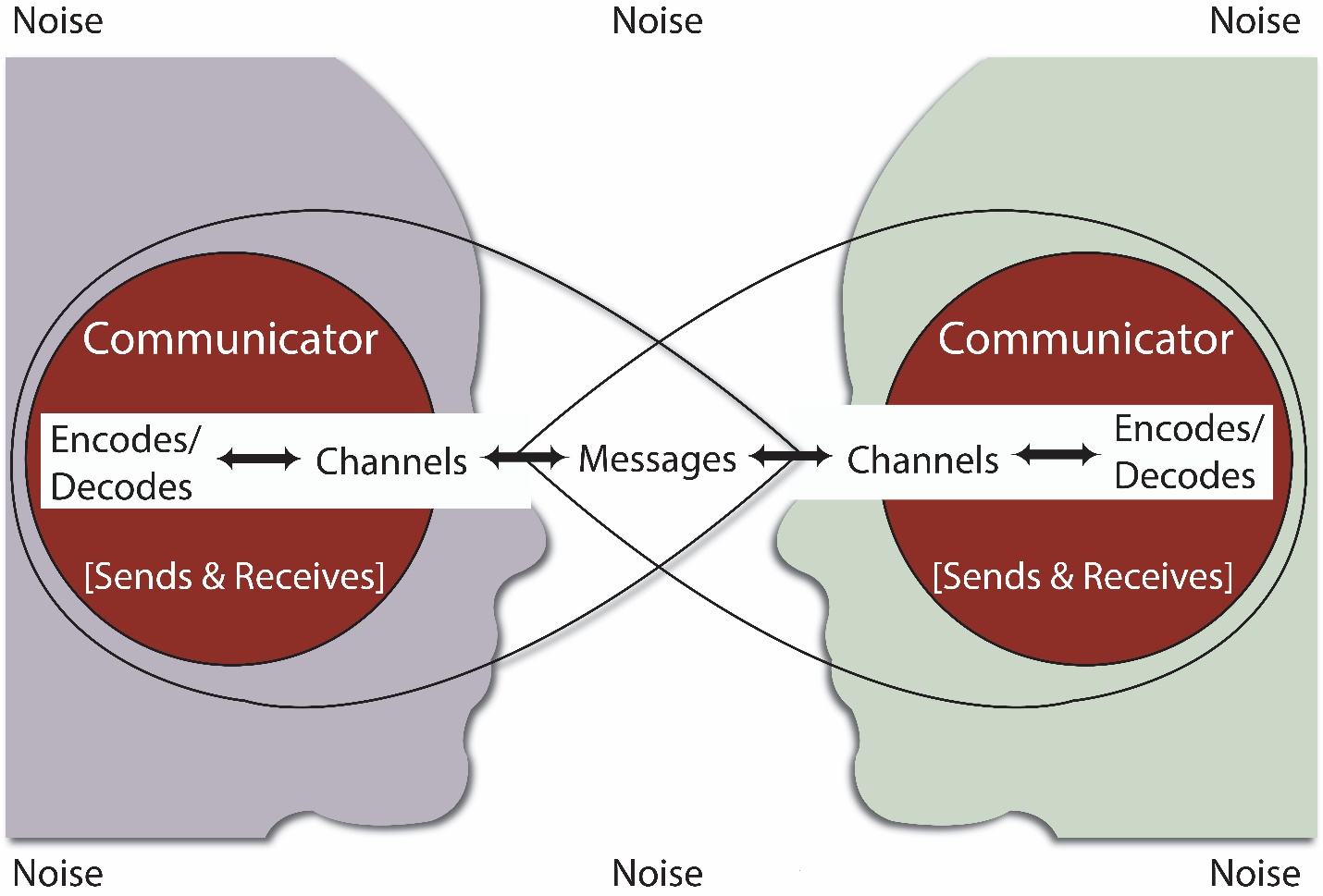

Barnlund’s Transactional Model

In 1970, Dean C. Barnlund created the transactional model of communication to understand basic interpersonal communication.26 Barnlund argues that one of the problems with the more linear models of communication is that they resemble mediated messages. The message gets created, the message is sent, and the message is received. For example, we write an email, we send an email, and the email is read. Instead, Barnlund argues that during interpersonal interactions, we are both sending and receiving messages simultaneously. Out of all the other communication models, this one includes a multi-layered feedback system. We can provide oral feedback, but our nonverbal communication (e.g., tone of voice, eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, etc.) is equally important to how others interpret the messages we are sending we use others’ nonverbal behaviors to interpret their messages. As such, in any interpersonal interaction, a ton of messages are sent and received simultaneously between the two people.

The Importance of Cues

The main components of the model include cues. There are three types of cues: public, private, and behavioral. Public cues are anything that is physical or environmental. Private cues are referred to as the private objects of the orientation, which include the senses of a person. Behavioral cues include nonverbal and verbal cues.

The Importance of Context

Furthermore, the transactional model of communication has also gone on to represent that three contexts coexist during an interaction:

- Social Context: The rules and norms that govern how people communicate with one another.

- Cultural Context: The cultural and co-cultural identities people have (e.g., ability, age, biological sex, gender identity, ethnicity, nationality, race, sexual orientation, social class, etc.).

- Relational Context: The nature of the bond or emotional attachment between two people (e.g., parent/guardian-child, sibling-sibling, teacher-student, health care worker-client, best friends, acquaintances, etc.).

Through our interpersonal interactions, we create social reality, but all of these different contexts impact this reality.

The Importance of Noise

Another important factor to consider in Barnlund’s Transactional Model is the issue of noise, which includes things that disturb or interrupt the flow of communication. Like the three contexts explored above, there are another four contexts that can impact our ability to interact with people effectively:27

- Physical Context: The physical space where interaction is occurring (office, school, home, doctor’s office, is the space loud, is the furniture comfortable, etc.).

- Physiological Context: The body’s responses to what’s happening in its environment.

- Internal: Physiological responses that result because of our body’s internal processes (e.g., hunger, a headache, physically tired, etc.).

- External: Physiological responses that result because of external stimuli within the environment (e.g., are you cold, are you hot, the color of the room, are you physically comfortable, etc.).

- Psychological Context: How the human mind responds to what’s occurring within its environment (e.g., emotional state, thoughts, perceptions, intentions, mindfulness, etc.).

- Semantic Context: The possible understanding and interpretation of different messages sent (e.g., someone’s language, size of vocabulary, effective use of grammar, etc.).

In each of these contexts, it’s possible to have things that disturb or interrupts the flow of communication. For example, in the physical context, hard plastic chairs can make you uncomfortable and not want to sit for very long talking to someone. Physiologically, if you have a headache (internal) or if a room is very hot, it can make it hard to concentrate and listen effectively to another person. Psychologically, if we just broke up with our significant other, we may find it difficult to sit and have a casual conversation with someone while our brains are running a thousand miles a minute. Semantically, if we don’t understand a word that someone uses, it can prevent us from accurately interpreting someone’s messages. When you think about it, with all the possible interference of noise that exists within an interpersonal interaction, it’s pretty impressive that we ever get anything accomplished.

More often than not, we are completely unaware of how these different contexts create noise and impact our interactions with one another during the moment itself. For example, think about the nature of the physical environments of fast-food restaurants versus fine dining establishments. In fast-food restaurants, the décor is bright, the lighting is bright, the seats are made of hard surfaces (often plastic), they tend to be louder, etc. This noise causes people to eat faster and increase turnover rates. Conversely, fine dining establishments have tablecloths, more comfortable chairs, dimmer lighting, quieter dining, etc. The physical space in a fast-food restaurant hurries interaction and increases turnover. The physical space in the fine dining restaurant slows our interactions, causes us to stay longer, and we spend more money as a result. However, most of us don’t pay that much attention to how physical space is impacting us while we’re having a conversation with another person.

Although we used the external environment here as an example of how noise impacts our interpersonal interactions, we could go through all of these contexts and discuss how they impact us in ways of which we’re not consciously aware. We’ll explore many of these contexts throughout the rest of this book.

Transaction Principles

As you can see, these models of communication are all very different. They have similar components, yet they are all conveyed very differently. Some have features that others do not. Nevertheless, there are transactional principles that are important to learn about interpersonal communication.

Communication is Complex

People might think that communication is easy. However, there are a lot of factors, such as power, language, and relationship differences, that can impact the conversation. Communication isn’t easy, because not everyone will have the same interpretation of the message. You will see advertisements that some people will love and others will be offended by. The reason is that people do not identically receive a message.

Communication is Continuous

In many of the communication models, we learned that communication never stops. Every time a source sends a message, a receiver will decode it, and it goes back-and-forth. It is an endless cycle, because even if one person stops talking, then they have already sent a message that the communication needs to end. As a receiver, you can keep trying to send messages, or you can stop talking as well, which sends the message to the other person that you also want to stop talking.

Communication is Dynamic

With new technology and changing times, we see that communication is constantly changing. Before social media, people interacted very differently. Some people have suggested that social media has influenced how we talk to each other. The models have changed over time because people have also changed how they communicate. People no longer use the phone to call other people; instead, they will text message others because they find it easier and less evasive.

Final Note

The advantage of this model is it shows that there is a shared field of experience between the sender and receiver. The transactional model shows that messages happen simultaneously with noise. However, the disadvantages of the model are that it is complex, and it suggests that the sender and receiver should understand the messages that are sent to each other.

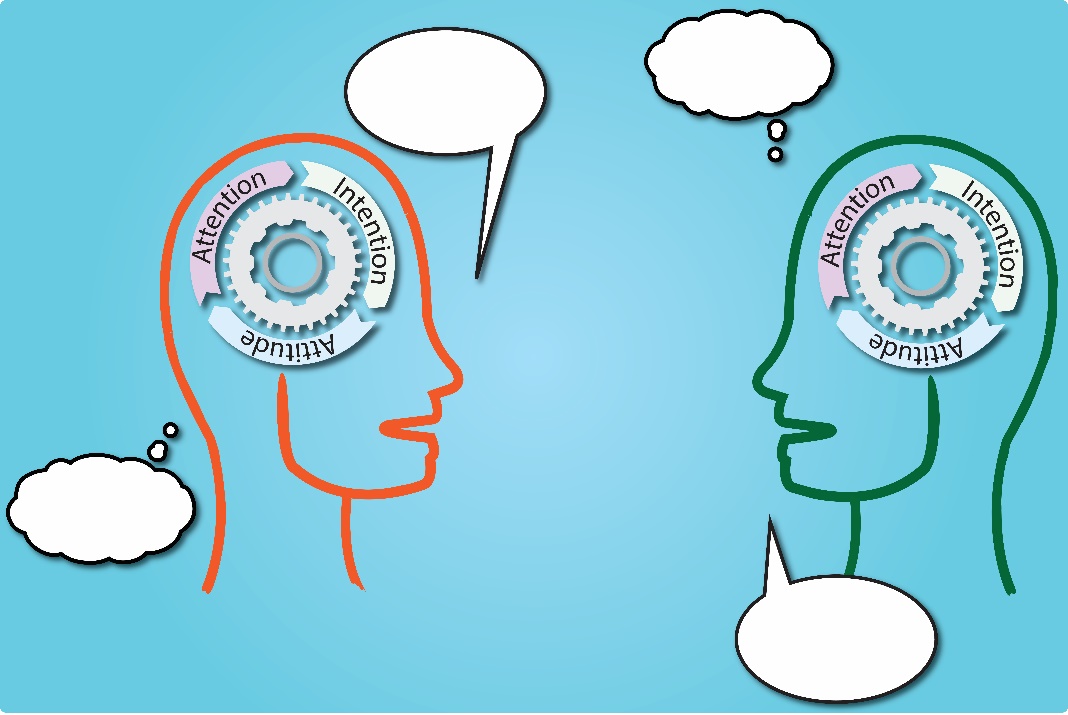

Towards a Model of Mindful Communication

So, what ultimately does a model of mindful communication look like? Well, to start, we think mindful communication is very similar to the transactional model of human communication. All of the facets of transactional communication can be applied in this context as well. The main addition to the model of mindful communication is coupling what we already know about the transactional model with what we learned in Chapter 1 about mindfulness. In Figure 2.9, we have combined the transactional model with Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson’s three parts of mindful practice: attention, intention, and attitude.28

We’re not proposing a new model of communication in this text; we’re proposing a new way of coupling interpersonal communication with mindfulness. So, how would mindful interpersonal communication work? According to Levine Tatkin, “Mindful communication is all about being more conscious about the way you interact with the other person daily. It is about being more present when the other person is communicating to you.”29 As such, we argue that mindful communication is learning to harness the power of mindfulness to focus our ability to communicate with other people interpersonally effectively.

Many of us engage in mindless communication every day. We don’t pay attention to the conversation; we don’t think about our intentions during the interaction; and we don’t analyze our attitudes while we talk. Have you ever found yourself doing any of the following during an interpersonal interaction?

- Constantly checking your smartphone.

- Focusing on anything but the other person talking.

- Forming your responses before the other person stops talking.

- Cutting the other person off while they are talking.

- Constantly interrupting the other person while they are talking.

- Getting impatient when the other person doesn’t “get to the point fast enough.”

- Trying to come up with solutions the person never asked for.

- Getting bored.

- Having biases against the other person or their ideas without really listening to them.

- Starting arguments for no reason.

- Finding yourself yelling or screaming at someone else.

- Refusing to “give in” or “find the middle ground” when engaged in conflict.

These are just a few examples of what mindless interpersonal interactions can look like when we don’t consider the attention, intention, and attitude. Mindful interpersonal communication, on the other hand, occurs when we engage in the following communication behaviors:30

- Listening to your partner without being distracted.

- Holding a conversation without being too emotional.

- Being non-judgmental when you talk, argue, or even fight with your partner.

- Accepting your partner’s perspective even if it is different from yours.

- Validating yourself and your partner.

The authors of this text truly believe that engaging in mindful interpersonal communicative relationships is very important in our day-to-day lives. All of us are bombarded by messages, and it’s effortless to start treating all messages as if they were equal and must be attended to within a given moment. Let’s look at that first mindless behavior we talked about earlier, checking your cellphone while you’re talking to people. As we discussed in Chapter 1, our minds have a habit of wandering 47% of the time.31 Our monkey brains are constantly jumping from idea to idea before we add in technology. If you’re continually checking your cellphone while you’re talking to someone, you’re allowing your brain to roam even more than it already does.

Effective interpersonal communication is hard. The goal of a mindful approach to interpersonal communication is to train ourselves to be in the moment with someone listening and talking. We’ll talk more about listening and talking later in this text. For now, we’re going to wrap-up this chapter by looking at some specific skills to enhance your interpersonal communication.

Key Takeaways

- In action models, communication was viewed as a one-directional transmission of information from a source or sender to some destination or receiver. These models include the Shannon and Weaver Model, the Schramm Model and Berlo’s SMCR model.

- Interactional models viewed communication as a two-way process, in which both the sender and the receiver equally share the responsibility for communication effectiveness. Examples of the interactional model are Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson Model and Osgood and Schramm Model.

- The transactional models differ from the interactional models in that the transactional models demonstrate that individuals are often acting as both the sender and receiver simultaneously. An example of a transactional model is Barnlund’s model.

Exercises

- Choose one action model, one interactional model, and Barnlund’s transactional model. Use each model to explain one communication scenario that you create. What are the differences in the explanations of each model?

- Choose the communication model with which you most agree. Why is it better than the other models?

2.5 Interpersonal Communication Skills

Learning Objectives

- Understand the skills associated with effective interpersonal skills.

- Explain how to improve interpersonal skills.

- Describe the principles of ethical communication.

In this chapter, we have learned about different aspects of interpersonal communication. Overall, some skills can make you a better interpersonal communicator. We will discuss each one in more detail below.

Listening Skills

The most important part of communication is not the actual talking, but the listening part. If you are not a good listener, then you will not be a good communicator. One must engage in mindful listening. Mindful listening is when you give careful and thoughtful attention to the messages that you receive. People will often listen mindfully to important messages or to people that matter most. Think about how happy you get when you are talking to someone you really love or maybe how you pay more attention to what a professor says if they tell you it will be on the exam. In each of these scenarios, you are giving the speaker your undivided attention. Most of our listening isn’t mindful, but there will be times where it will be important to listen to what others are telling us so that we can fulfill our personal and/or professional goals. We’ll discuss listening in more detail in Chapter 7.

People Skills

People skills are a set of characteristics that will help you interact well with others.32 These skills are most important in group situations and where cooperation is needed. These skills can also relate to how you handle social situations. They can make a positive impact on career advancement but also in relationship development.33 One of the most essential people skills to have is the ability to understand people. Being able to feel empathy or sympathy to another person’s situation can go a long way. By putting yourself in other people’s shoes and understanding their hardships or differences, you can put things into perspective. It can help you build a stronger and better interpersonal relationship.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EQ) is the ability to recognize your own emotions and the emotions of others.34 Emotionally intelligent people can label their feelings appropriately and use this information to guide their behavior. EQ is highly associated with the ability to empathize with others. Furthermore, EQ can help people connect interpersonally. Research has demonstrated that people with higher levels of EQ are more likely to succeed in the workplace and have better mental health. They are often better leaders and effective managers of conflict. We’ll discuss the idea of EQ in more detail in Chapter 3.

Appropriate Skill Selection

The best interpersonal communicators are the ones who can use the appropriate skill in certain contexts. For instance, if it is a somber event, then they might not laugh. Or if it is a joyful occasion, they might not cry hysterically, unless they are tears of joy. The best politicians can sense the audience and determine what skills would be appropriate for which occasion. We know that humor can be beneficial in certain situations. However, humor can also be inappropriate for certain people. It is essential to know what skill is appropriate to use and when it is necessary to use it.

Communicating Ethically

The last interpersonal skill involves communication ethics. We have seen several people in the business world that have gotten in trouble for not communicating ethically. It is important to be mindful of what you say to others. You do not want people to think you are deceptive or that you are lying to them. Trust is a hard thing to build. Yet, trust can be taken away from you very quickly. It is essential that every time you communicate, you should consider the ethics behind your words. As we will see throughout this book, words matter! So, what does it mean to communicate ethically interpersonally? Thankfully, the National Communication Association has created a general credo for ethical communication.35 The subheadings below represent the nine statements created by the National Communication Association to help guide conversations related to communication ethics.

We advocate truthfulness, accuracy, honesty, and reason as essential to the integrity of communication.

The first statement in the credo for ethical communication is one that has taken on a lot more purpose in the past few years, being truthful. We live in a world where the blurring of fact and fiction, real-life and fantasy, truth and lies, real news and fake news, etc. has become increasingly blurry. The NCA credo argues that ethical communication should always strive towards truth and integrity. As such, it’s important to consider our interpersonal communication and ensure that we are not spreading lies.

We endorse freedom of expression, diversity of perspective, and tolerance of dissent to achieve the informed and responsible decision making fundamental to a civil society.

You don’t have to agree with everyone. In fact, it’s perfectly appropriate to disagree with people and do so in a civilized manner. So much of our interpersonal communication in the 21st Century seems to have become about shouting, “I’m right, you’re wrong.” As such, it’s important to remember that it’s possible for many different vantage points to have equal value. From an ethical perspective, it’s very important to listen to others and not immediately start thinking about our comebacks or counter-arguments. When we’re only focused on our comebacks and counter-arguments, then we’re not listening effectively. Now, we are not arguing that people should have the right to their own set of facts. As we discussed in the previous statement, we believe in facts and think the idea of “alternative facts” is horrific. But often, people’s experiences in life lead them to different positions that can be equally valid.

We strive to understand and respect other communicators before evaluating and responding to their messages.

Along with what was discussed in the previous statement, it’s important to approach our interpersonal interactions from a position of understanding and respect. Part of the mindfulness approach to interpersonal communication that we’ve advocated for in this book involves understanding and respect. Too many people in our world today immediately shut down others with whom they disagree without ever giving the other person a chance. We know that it can be tough to listen to messages that you strongly disagree with, but we can still disagree and, at the end of the day, respect each other.

We promote access to communication resources and opportunities as necessary to fulfill human potential and contribute to the well‐being of individuals, families, communities, and society.

As communication scholars, we believe that everyone should have the opportunity to improve their communication. One of the reasons we’ve written this book is because we believe that all students should have access to an interpersonal communication textbook that is free. Furthermore, we believe that everyone should have the opportunity to develop their interpersonal communication skills, listening skills, presentation skills, and social skills. Ultimately, developing communication skills helps people in their interpersonal relationships and makes them better people as a whole. According to Sherwyn Morreale, Joseph Valenzano, and Janessa Bauer:

Communication can help couples connect on a deeper level and feel more satisfied with their relationships. Additionally, competent communication strengthens bonds among family members and helps them cope with conflict and stressful situations. Communication gives family members the tools they need to express their feelings and address their concerns in a constructive way, which ultimately helps when conflicts and stressful situations arise… Better interpersonal communication can improve the social health of a community by strengthening relationships among various community members.36