Chapter 1: Introduction to Human Communication

0.1 Introduction

If you’re like most people taking their first course or reading your first book in interpersonal communication, you may be wondering what it is that you’re going to be studying. Academics are notorious for not agreeing on definitions of concepts, which is also true of interpersonal communication scholars. Bochner (1989) wrote laid out the fundamental underpinnings of this academic area called “interpersonal communication,” “at least two communicators; intentionally orienting toward each other; as both subject and object; whose actions embody each other’s perspectives both toward self and toward other.”1 This simplistic definition of interpersonal communication frustrates many scholars because it does not provide clear parameters for the area of study beyond two people interacting. Mark Knapp and John Daly noted that four areas of contention are commonly seen in the discussion of interpersonal communication: number of communicators involved, the physical proximity of the communicators, nature of the interaction units, and degree of formality and structure.2

Number of Communicators Involved

As the definition from Bochner in the previous paragraph noted, most scholars agree that interpersonal communication involves “at least two communicators.” Although a helpful tool to separate interpersonal communication from small group or organizational communication, some scholars argue that looking specifically at one dyad is an accurate representation of interpersonal. For example, if you and your dating partner are talking about what a future together might look like, you cannot exclude all relational baggage that comes into that discussion. You might be influenced by your own family, friends, coworkers, and other associates. So although there may be only two people interacting at one point, there are strong influences that are happening in the background.

Physical Proximity of the Communicators

In a lot of early writing on the subject of interpersonal communication, the discussion of the importance of physical proximity was a common one. Researchers argued that interpersonal communication is a face-to-face endeavor. However, with the range of mediated technologies we have in the 21st Century, we often communicate interpersonally with people through social networking sites, text messaging, email, the phone, and a range of other technologies. Is the interaction between two lovers as they break up via text messages any less “interpersonal” than when the break up happens face-to-face? The issue of proximity is an interesting one, but we argue that in the 21st Century, so much of our interpersonal interactions do use some kind of technology.

Nature of the Interaction Units

One of our primary reasons for communicating with other people is trying to understand them and how and why they communicate. As such, some messages may help us understand and predict how people will behave and communicate, so do those interactions have a higher degree of “interpersonalness?” Imagine you and your boyfriend or girlfriend just fought. You are not sure what caused the fight in the first place. During the ensuing conversation (once things have settled down), you realize that your boyfriend/girlfriend feels that when you flirt with others in public, it diminishes your relationship. Through this conversation, you learn how your behavior causes your boyfriend/girlfriend to get upset and react angrily. You now have more information about how your boyfriend/girlfriend communicates and what your behavior does to cause these types of interactions. Some would argue this type of conversation has a high degree of “interpersonalness.” On the other hand, if you “like” a stranger’s post on Facebook, have you engaged in interpersonal communication? Is this minimal form of interaction even worth calling interpersonal communication?

Degree of Formality and Structure

The final sticking point that many scholars have when discussing interpersonal communication is the issue of formality and structure. A great deal of research in interpersonal communication has focused on interpersonal interactions that are considered informal and unstructured (e.g., friendships, romantic relationships, family interactions, etc.). However, numerous interpersonal interactions do have a stronger degree of formality and structure associated with them. For example, you would not interact with your physician the same way you would with your romantic partner because of the formality of that relationship. We often communicate with our managers or supervisors who exist in a formal organizational structure. In all of these cases, we are still examining interpersonal relationships.

1.1 Why Study Communication?

Learning Objectives

- Understand communication needs.

- Discuss physical needs.

- Explain identity needs.

- Describe social needs.

- Elucidate practical needs.

Most people think they are great communicators. However, very few people are “naturally” good. Communication takes time, skill, and practice. To be a great communicator, you must also be a great listener. It requires some proficiency and competence. Think about someone you know that is not a good communicator. Why is that person not good? Do they say things that are inappropriate, rude, or hostile? This text is designed to give you the skills to be a better communicator.

Reasons to Study Communication

Hence, we need to study communication for a variety of reasons. First, it gives us a new perspective at something we take for granted every day. As stated earlier, most people think they are excellent communicators. However, most people never ask another person if they are great communicators. Besides being in a public speaking class or listening to your friends’ opinions, you probably do not get a lot of feedback on the quality of your communication. In this book, we will learn all about communication from different aspects. As the saying goes, “You can’t see the forest from the trees.” In other words, you won’t be able to see the impact of your communication behaviors, if you don’t focus on certain communication aspects. The second reason we study communication is based on the quantity of our time that is devoted to that activity. Think about your daily routine; I am sure that it involves communicating with others (via face-to-face, texting, electronic media, etc.). Because we spend so much of our time communicating with others, we should make that time worthwhile. We need to learn how to communicate and communicate better because a large amount of our time is allotted to communicating with others. The last reason why we study communication is to increase our effectiveness. There are several reasons why marriages and relationships often fail. The most popular reason is that people don’t know how to communicate with each other, which leads to irreconcilable differences. People often do not know how to work through problems, and it creates anger, hostility, and possibly violence. In these cases, communication needs to be effective for the relationship to work and be satisfying. Think about all the relationships that you have with friends, family, coworkers, and significant others. It is possible that this course could make you more successful in those relationships.

We all have specific and general reasons why we communicate with others. They vary from person to person. We know that we spend a large amount of our time communicating. Also, every individual will communicate with other people. Most people do not realize the value and importance of communication. Sherry Morreale and Judy Pearson believe that there are three main reasons why we need to study communication.3 First of all, when you study communication behaviors, it gives you a new perspective on something you probably take for granted. Some people never realize the important physiological functions until they take a class on anatomy or biology. In the same fashion, some people never understand how to communicate and why they communicate until they take a communication studies course. Second, we need to study communication because we spend a large portion of our time communicating with other people. Gina Chen found that many people communicate online every day, and Twitter subscribers fulfill their needs of camaraderie by tweeting with others.4 Hence, we all need to communicate with others. Third, the most important reason is to become a better communicator. Research has shown that we need to learn to communicate better with others because none of us are very good at it.

Communication Needs

Think for a minute of all the problematic communication behaviors that you have experienced in your life: personally or professionally. You will probably notice that there are areas that could use improvement. In this book, we will learn about better ways to communicate. To improve your communication behaviors, you must first understand the needs for communicating with others.

Physical

Studies show that there is a link between mental health and physical health. In other words, people who encounter negative experiences, but are also willing to communicate those experiences are more likely to have better mental and physical health.5 Ronald Adler, Lawrence Rosenfeld, and Russell Proctor found that communication has been beneficial to avoiding/decreasing:6

Research clearly illustrates that communication is so vital for our physical health. Because most health problems are stress-induced, communication offers a way to relieve this tension and alleviate some of the physical symptoms. It is so vital for people to share what they feel, because if they keep it bottled up, then they are more likely to suffer emotionally, mentally, and physically.

Identity

Communication is not only essential for us to thrive and live. It is also important to discover who we are. From a very young age, you were probably told a variety of characteristics about your physical appearance and your personality. You might have been told that you are funny, smart, pretty, friendly, talented, or insightful. All of these comments probably came from someone else. For instance, Sally went to a store without any makeup and saw one of her close friends. Sally’s friend to her that she looked horrible without any makeup. So, from that day forward, she never walked out of the house without her cosmetics. You can see that this one comment affected Sally’s behavior but also her perceptions about herself. Just one comment can influence how you think, act, and feel. Think about all the comments that you have been told in your life. Were they hurtful comments or helpful comments? Did they make you stronger or weaker? You are who you are based on what others have told you about yourself and how you responded to these comments. In another opposite example, Mark’s parents told him that he wasn’t very smart and that he would probably amount to nothing. Mark used these comments to make himself better. He studied harder and worked harder because he believed that he was more than his parents’ comments. In this situation, you can see that the comments helped shaped his identity differently in a positive manner.

Social

Other than using words to identify who we are, we use communication to establish relationships. Relationships exist because of communication. Each time we talk to others, we are sharing a part of ourselves with others. We know that people who have strong relationships with others are due to the conversations that they have with others. Think about all the relationships that you are involved with and how communication differs in those relationships. If you stopped talking to the people you care about, your relationships might suffer. The only way relationships can grow is when communication occurs between individuals. Joy Koesten analyzed family communication patterns and communication competence. She found that people who grew up in more conversation oriented families were also more likely to have better relationships than people who grew up in lower conversation oriented families.7

Practical

Communication is a key ingredient in our life. We need it to operate and do our daily tasks. Communication is the means to tell the barista what coffee you prefer, inform your physician about what hurts, and advise others that you might need help.

We know that communication helps in the business setting. Katherine Kinnick and Sabrena Parton maintained that communication is important in workplace settings. They found that the ability to persuade effectively was very important. Moreover, females are evaluated more on their interpersonal skills than males, and males were evaluated more on their leadership skills than interpersonal skills.8 Overall, we know that to do well in the business setting, one must learn to be a competent communicator.

Moreover, we know that communication is not only crucial in professional settings but in personal settings. Daniel Canary, Laura Stafford, and Beth Semic found that communication behaviors are essential in marriages because it adds the relationship features.9 In another study, Laura Stafford and Daniel Canary illustrated the importance of communication in dating relationships.10 All in all, communication is needed for users to relate to others, build connections, and help our relationships exist.

Key Takeaways

- We need communication. We need to be able to study communication because we spend so much time doing it, we could learn to be more effective at it, and it is something we have done for a long time.

- Research has shown us that communication can help us with physical needs. When we are hungry or thirsty, we can tell someone this, but also it helps to release stress.

- To maintain, create, or terminate relationships, we need communication. Communication helps fulfill our social needs to connect with others.

- To function, we need communication for practical needs.

Exercises

- Think of an example for each communication need. Which need is most important for you? Why?

- Why do you think it is important to study communication? Is this class required for you? Do you think it should be a requirement for everyone?

- Think about how your identity has been shaped by others. What is something that was said to you that impacted how you felt? How do you feel now about the comment?

1.2 Basic Principles of Human Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define and explain the term “communication.”

- Describe the nature of symbols and their importance to human communication.

- Explain seven important factors related to human communication.

The origin of the word communication can be traced back to the Latin word communico, which is translated to mean “to join or unite,” “to connect,” “to participate in” or “to share with all.” This root word is the same one from which we get not only the word communicate, but also common, commune, communion, and community. Thus, we can define communication as a process by which we share ideas or information with other people. We commonly think of communication as talking, but it is much broader than just speech. Other characteristics of voice communicate messages, and we communicate, as well, with eyes, facial expressions, hand gestures, body position, and movement. Let us examine some basic principles about how we communicate with one another.

Communication Is Symbolic

Have you ever noticed that we can hear or look at something like the word “cat” and immediately know what those three letters mean? From the moment you enter grade school, you are taught how to recognize sequences of letters that form words that help us understand the world. With these words, we can create sentences, paragraphs, and books like this one. The letters used to create the word “cat” and then the word itself is what communication scholars call symbols. A symbol is a mark, object, or sign that represents something else by association, resemblance, or convention.

Let’s think about one of the most important words commonly tossed around, love. The four letters that make of the word “l,” “o,” “v,” and “e,” are visual symbols that, when combined, form the word “love,” which is a symbol associated with intense regard or liking. For example, I can “love” chocolate. However, the same four-letter word has other meanings attached to it as well. For example, “love” can represent a deeply intimate relationship or a romantic/sexual attachment. In the first case, we could love our parents/guardians and friends, but in the second case, we experience love as a factor of a deep romantic/sexual relationship. So these are just three associations we have with the same symbol, love. In Figure 1.2, we see American Sign Language (ASL) letters for the word “love.” In this case, the hands themselves represent symbols for English letters, which is an agreed upon convention of users of ASL to represent “love.”

Symbols can also be visual representations of ideas and concepts. For example, look at the various symbols in Figure 1.3 of various social media icons. In this image, you see symbols for a range of different social media sites, including Facebook (lowercase “f”), Twitter (the bird), Snap Chat (the ghost image), and many others. Admittedly, the icons for YouTube and dig just use their names, but these images have become associated with these online platforms over many years.

The Symbol is Not the Thing

Now that we’ve explained what symbols are, we should probably offer a few very important guides. First, the symbol is not the thing that it is representing. For example, the word “dog” is not a member of the canine family that greets you when you come home every night. If we look back at those symbols listed in Figure 1.2, those symbols are not the organizations themselves. “g+” is not Google Plus. The actual thing that is “Google Plus” is a series of computer code that exists on the World Wide Web that allows us, people, to interact.

Arbitrariness of Symbols

How we assign symbols is entirely arbitrary. For example, in Figure 1.4, we see two animals that are categorized under the symbols “dog” and “cat.” In this image, the “dog” is on the left side, and the “cat” is on the right side. The words we associate with these animals only exist because we have said it’s so for many, many years. Back when humans were labeling these animals, we could just have easily called the one on the left “cat” and the one on the right “dog,” but we didn’t. If we called the animal on the left “cat,” would that change the nature of what that animal is? Not really. The only thing that would change is the symbol we have associated with that animal.

Let’s look at another symbolic example you are probably familiar with – :). The “smiley” face or the two pieces of punctuation (colon followed by closed parentheses). This symbol may seem like it’s everywhere today, but it’s only existed since September 1982. In early September 1982, a joke was posted on an electronic bulletin board about a fake chemical spill at Carnegie Mellon University. At the time, there was no easy way to distinguish between serious versus non-serious information. A computer scientist named Scott E. Fahlman entered the debate with the following message:

The Original Emoticons

I propose that [sic] the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use:

:-(

Thus the first emoticon, a sequence of keyboard characters used to represent facial expressions or emotions, was born. Even the universal symbol for happiness, the yellow circle with the smiling face, had only existed since 1963 when graphic artist Harvey Ross Ball created it. The happy face was created as a way to raise employee morale at State Mutual Life Assurance Company of Worcester, Massachusetts. Of course, when you merge the happy face with emoticons, we eventually ended up with emojis (Figure 1.5). Of course, many people today just take emojis for granted without ever knowing their origin at all.

Communication Is Shared Meaning

Hopefully, in our previous discussion about symbols, you noticed that although the assignment of symbols to real things and ideas is arbitrary, our understanding of them exists because we agree to their meaning. If we were talking and I said, “it’s time for tea,” you may think that I’m going to put on some boiling water and pull out the oolong tea. However, if I said, “it’s time for tea” in the United Kingdom, you would assume that we were getting ready for our evening meal. Same word, but two very different meanings depending on the culture one uses the term. In the United Kingdom, high tea (or meat tea) is the evening meal. Dinner, on the other hand, would represent the large meal of the day, which is usually eaten in the middle of the day. Of course, in the United States, we refer to the middle of the day meal as lunch and often refer to the evening meal as dinner (or supper).

Let’s imagine that you were recently at a party. Two of your friends had recently attended the same Broadway play together. You ask them “how the play was,” and here’s how they responded:

So, we got to the theatre 20 minutes early to ensure we were able to get comfortable and could do some people watching before the show started. The person sitting in front of us had the worst comb-over I had ever seen. Half through Act 1, the hair was flopping back in our laps like the legs of a spider. I mean, those strands of hair had to be 8 to 9 inches long and came down on us like it was pleading with us to rescue it. Oh, and this one woman who was sitting to our right was wearing this huge fur hat-turban thing on her head. It looked like some kind of furry animal crawled up on her head and died. I felt horrible for the poor guy that was sitting behind her because I’m sure he couldn’t see anything over or around that thing.

Here’s is how your second friend described the experience:

I thought the play was good enough. It had some guy from the UK who tried to have a Brooklyn accent that came in and out. The set was pretty cool though. At one point, the set turned from a boring looking office building into a giant tree. That was pretty darn cool. As for the overall story, it was good, I guess. The show just wasn’t something I would normally see.

In this case, you have the same experience described by two different people. We are only talking about the experience each person had in an abstract sense. In both cases, you had friends reporting on the same experience but from their perceptions of the experience. With your first friend, you learn more about what was going on around your friend in the theatre but not about the show itself. The second friend provided you with more details about her perception of the play, the acting, the scenery, and the story. Did we learn anything about the content of the “play” through either conversation? Not really.

Many of our conversations resemble this type of experience recall. In both cases, we have two individuals who are attempting to share with us through communication specific ideas and meanings. However, sharing meaning is not always very easy. In both cases, you asked your friends, “how the play was.” In the first case, your friend interpreted this phrase as being asked about their experience at the theatre itself. In the second case, your friend interpreted your phrase as being a request for her opinion or critique of the play. As you can see in this example, it’s very easy to get very different responses based on how people interpret what you are asking.

Communication scholars often say that “meanings aren’t in words, they’re in people” because of this issue related to interpretation. Yes, there are dictionary definitions of words. Earlier in this chapter, we provided three different dictionary-type definitions for the word “love:” 1) intense regard or liking, 2) a deeply intimate relationship, or 3) a romantic/sexual attachment. These types of definitions we often call denotative definitions. However, it’s also important to understand that in addition to denotative definitions, there are also connotative definitions, or the emotions or associations a person makes when exposed to a symbol. For example, how one personally understands or experiences the word “love” is connotative. The warm feeling you get, the memories of experiencing love all come together to give you a general, personalized understanding of the word itself. One of the biggest problems that occur is when one person’s denotative meaning conflicts with another person’s connotative meaning. For example, when I write the word “dog,” many of you think of four-legged furry family members. If you’ve never been a dog owner, you may just generally think about these animals as members of the canine family. If, however, you’ve had a bad experience with a dog in the past, you may have very negative feelings that could lead you to feel anxious or experience dread when you hear the word “dog.” As another example, think about clowns. Some people see clowns as cheery characters associated with the circus and birthday parties. Other people are genuinely terrified by clowns. Both the dog and clown cases illustrate how we can have symbols that have different meanings to different people.

Communication Involves Intentionality

One area that often involves a bit of controversy in the field of communication is what is called intentionality. Intentionality asks whether an individual purposefully intends to interact act with another person and attempt shared meaning. Each time you communicate with others, there is intentionality involved. You may want to offer your opinions or thoughts on a certain topic. However, intentionality is an important concept in communication. Think about times where you might have talked aloud without realizing another person could hear you. Communication can occur at any time. When there is intent among the parties to converse with each other, then it makes the communication more effective.

Others argue that you “cannot, not communicate.” This idea notes that we are always communicating with those around us. As we’ll talk more about later in this book, communication can be both verbal (the words we speak) and nonverbal (gestures, use of space, facial expressions, how we say words, etc.). From this perspective, our bodies are always in a state of nonverbal communication, whether it’s intended or not. Maybe you’ve walked past someone’s office and saw them hunched over at their desk, staring at a computer screen. Based on the posture of the other person, you decide not to say “hi” because the person looks like they are deep in thought and probably busy. In this case, we interpret the person’s nonverbal communication as saying, “I’m busy.” In reality, that person could just as easily be looking at Facebook and killing time until someone drops by and says, “hi.”

Dimensions of Communication

When we communicate with other people, we must always remember that our communication is interpreted at multiple levels. Two common dimensions used to ascertain meaning during communication are relational and content.

Relational Dimension

Every time we communicate with others, there is a relational dimension. You can communicate in a tone of friendship, love, hatred, and so forth. This is indicated in how you communicate with your receiver. Think about the phrase, “You are crazy!” It means different things depending on the source of the message. For instance, if your boss said it, you might take it harsher than if your close friend said it to you. You are more likely to receive a message more accurately when you can define the type of relationship that you have with this person. Hence, your relationship with the person determines how you are more likely to interpret the message. Take another example of the words “I want to see you now!” These same words might mean different things if it comes from your boss or if it comes from your lover. That is, pretending that your boss is not your lover. You will know that if your boss wants to see you, then it is probably an urgent matter that needs your immediate attention. However, if your lover said it, then you might think that they miss you and can’t bear the thought about being without you for too long.

Content Dimension

In the same fashion, every time we speak, we have a content dimension. The content dimension is the information that is stated explicitly in the message. When people focus on the content of a message, then ignore the relationship dimension. They are focused on the specific words that were used to convey the message. For instance, if you ran into an ex-lover who said “I’m happy for you” about your new relationship. You might wonder what that phrase means. Did it mean that your ex was truly happy for you, or if they were happy to see you in a new relationship, or if your ex thinks that you are happy? One will ponder many interpretations of the message, especially if a relationship is not truly defined.

Another example might be a new acquaintance who talks about how your appearance looks “interesting.” You might be wondering if your new friend is sarcastic, or if they just didn’t know a nicer way of expressing their opinion. Because your relationship is so new, you might think about why they decided to pick that term over another term. Hence, the content of a message impacts how it is received.

Communication Is a Process

The word “process” refers to the idea that something is ongoing, dynamic, and changing with a purpose or towards some end. A communication scholar named David K. Berlo was the first to discuss human communication as a process back in 1960.11 We’ll examine Berlo’s ideas in more detail in Chapter 2, but for now, it’s important to understand the basic concept of communication as a process. From Berlo’s perspective, communication is a series of ongoing interactions that change over time. For example, think about the number of “inside jokes” you may have with your best friend. Sometimes you can get to the point where all you say is one word, and both of you can crack up laughing. This level of familiarity and short-hand communication didn’t exist when you first met but has developed over time. Ultimately, the more interaction you have with someone, the more your relationship with that person will evolve.

Communication Is Culturally Determined

The word culture refers to a “group of people who through a process of learning can share perceptions of the world that influences their beliefs, values, norms, and rules, which eventually affect behavior.”12 Let’s breakdown this definition. First, it’s essential to recognize that culture is something we learn. From the moment we are born, we start to learn about our culture. We learn culture from our families, our schools, our peers, and many other sources as we age. Specifically, we learn perceptions of the world. We learn about morality. We learn about our relationship with our surroundings. We learn about our places in a greater society. These perceptions ultimately influence what we believe, what we value, what we consider “normal,” and what rules we live by. For example, many of us have beliefs, values, norms, and rules that are directly related to the religion we were raised. As an institution, religion is often one of the dominant factors of culture around the world.

Let’s start by looking at how religion can impact beliefs. Your faith can impact what you believe about the nature of life and death. For some, you live well and you’ll go to a happy place (Heaven, Nirvana, Elysium, etc.) or a negative place (Hell, Samsara, Tartarus, etc.). We should mention that Samsara is less a “place” and more the process of reincarnation as well as one’s actions and consequences from the past, present, and future.

Religion can also impact what you value. Cherokee are taught to value the earth and the importance of keep balance with the earth. Some members of Judaic religions, on the other hand, view passages that give Adam the directive to “subdue” the earth, as an indication of a hierarchy placing humans in charge of the earth. As such, the value is more on what the earth can provide than on ensuring harmony with nature.

Religion can also impact what you view as “normal.” Many religions stress the importance of female modesty, so it is normal for women to wear specific dress to ensure they do not show their figures or little to no skin. On the other hand, one branch of Raëlianism promotes a pro-sex feminist stance where nudity and sex work are normal and even celebrated.

Different religions have different rules that get created and handed down. For most Western readers, the most famous set of rules is probably the Judaic Tradition’s Ten Commandments. Conversely, Hindus have a text of religious laws transmitted in the Vedas. Most major religions have, at some point or another, had religious texts that became enshrined laws within those societies.

Finally, these beliefs, values, norms, and rules ultimately impact how all of us interact and behave with others. The critical part to remember about these actual behaviors is that we often have no idea how (and to what degree) our culture influences our communicative behavior until we are interacting with someone from a culture that differs from ours. We’ll talk more about issues of intercultural interpersonal interactions later in this text.

Communication Occurs in a Context

Another factor that influences how we understand others is the context, the circumstance, environment, setting, and/or situation surrounding an interaction. Most people learning about context are generally exposed during elementary school when you are trying to figure out the meaning of a specific word. You may have seen a complicated word and told to use “context clues” to understand what the word means. In the same vein, when we analyze how people are communicating, we must understand the context of that communication.

Imagine you’re hanging out at your local restaurant, and you hear someone at the next table say, “I can’t believe that guy. He’s always out in left field!” As an American idiom, we know that “out in left field” generally refers to something unexpected or unusual. The term stems out of baseball because the player who hangs out in left field has the farthest to throw to get a baseball back to the first baseman in an attempt to tag out a runner. However, if you were listening to this conversation in farmland, you could be hearing someone describe a specific geographic location (e.g., “He was out in left field chasing after a goat who stumbled that way”). In this case, context does matter.

Communication Is Purposeful

We communicate for different reasons. We communicate in an attempt to persuade people. We communicate to get people to like us. We communicate to express our liking of other people. We could list different reasons why we communicate with other people. Often we may not even be aware of the specific reason or need we have for communicating with others. We’ll examine more of the different needs that communication fulfills along with the motives we often have for communicating with others in Chapter 2.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is derived from the Latin root communico, which means to share. As communicators, each time we talk to others, we share part of ourselves.

- Symbols are words, pictures, or objects that we use to represent something else. Symbols convey meanings. They can be written, spoken, or unspoken.

- There are many aspects to communication. Communication involves shared meaning; communication is a process; has a relationship, intent, & content dimension; is culturally determined, occurs in context; and is communication is purposeful.

Exercises

- In groups, provide a real-life example for each of these aspects: Communication involves shared meaning, communication is a process, has a relationship, intent, & content dimension, occurs in a context, communication is purposeful, and it is culturally defined.

- As a class, come up with different words. Then, divide the class and randomly distribute the words. Each group will try to get the other group to guess their words either by drawing symbols or displaying nonverbal behaviors. Then discuss how symbols impact perception and language.

- Can you think of some examples of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis? For instance, in Japan, the word “backyard” does not exist. Because space is so limited, most Japanese people do not have backyards. This term is foreign to them, but in America, most of our houses have a backyard.

1.3 Communication Competence

Learning Objectives

- Explain Competence.

- Distinguish between social appropriateness and personal effectiveness and their relationship to communication competence.

- Identify characteristics of competence.

Defining Competence

Brian Spitzberg (2000) argued that communication competence involved being both appropriate and effective.13 Appropriate communication is what most people would consider acceptable behaviors. Effective communication is getting your desired personal outcome.

You might think about communicators who were appropriate and not effective and vice versa. The two characteristics go hand in hand. You need to have both to be considered competent. Think about coaches who might say horrible or inappropriate things to their players to motivate them. This may be viewed highly effective to others, but possibly very inappropriate to others. Especially if you are not used to harsh language or foul language, then your perceptions could hinder how you feel about the speaker. At the same time, you might have individuals that are highly appropriate but are not effective. They may say the right things, but cannot get any results. For instance, imagine a mother who is trying over and over to get her child to brush their teeth. She might try praises or persuasive techniques, but if the child doesn’t brush their teeth, then she is not accomplishing her goal. You truly need a balance between the two.

Understanding Competence

First of all, there is not the best or ultimate effective way of communicating that works for everyone. Think about the speakers that you know. Perhaps, some are very charismatic, humorous, assertive, and more timid than others. Just as there are many types of speakers and speaking styles, there are different types of competent communicators. For example, a joke in one context might be hilarious, but that same joke might be very offensive in another context. What this tells us is that there is no guaranteed or definite methods that will work in every situation. Communication that works in one context and not another depends on the culture and the characteristics of the person or persons receiving the message.

Moreover, we know that communication varies from one context to another. For instance, kindergarten teachers may be wonderful in a room full of five-year-olds, but if you asked them to present in a college classroom, they might get a little nervous because the situation is different. Some situations are better for certain speakers than others. Some people can rise to the occasion and truly deliver a memorable speech in a moment of crisis. However, if you asked them to do it again, they might not be able to do so because of the situational variables that influenced the speech. Some individuals are wonderful public speakers but are truly unable to communicate in interpersonal relationships and vice versa. These situations occur because some people feel more comfortable in certain settings than others. Hence, competency can vary depending on the type of communication.

Also, competence can be taught. The main reason why taking a communication course is so important is to be a better speaker. Hence, this is why many schools make it a requirement for college students. Think about an invention or idea you might have. If you can’t communicate that idea/invention, then it will probably never come to fruition.

Characteristics of Competence

Now that you know more about competence, it is important to note that competent communicators often share many similar characteristics. Studies on competence illustrate that competent communicators have distinctive characteristics that differ from incompetent communicators. We will discuss a few of these characteristics in this section.

Skillful

First, many competent communicators are skillful. In other words, they use situational cues to figure out which approach might be best. Think about a car salesperson and about how she/he will approach a customer who is wanting to make a purchase. If the salesperson is too aggressive, then they might lose a sale. For that reason, they need to cater to their customer and make sure that they meet their customer’s needs. The salesperson might directly approach the customer by simply saying, “Hi I’m Jamie, I would be happy to help you today,” or by asking questions like, “I see you looking at cars today. Are you interested in a particular model?”, or they could ask the customer to talk more by saying, “Can you tell me more about what you are looking for?” And perhaps, even complimenting the customer. Each of these strategies illustrates how a salesperson can be skillful in meeting the customer’s expectations and, at the same time, fulfilling their own goals. Just like a chef has many ingredients to use to prepare a dish, a competent communicator possesses many skills to use depending on the situation.

Adaptable

Second, competent communicators are adaptable. I am sure you might have seen a speaker who uses technology like PowerPoint to make their presentations. What happens if technology fails, does the speaker perform poorly as well? Competent communicators would not let technology stop them from presenting their message. They can perform under pressure and any type of constraint. For instance, if the communicator is presenting and notices that the audience has become bored, then they might change up their presentation and make it more exciting and lively to incite the audience.

Involved

Third, competent communicators can get others involved. Competent communicators think about their audience and being understood. They can get people excited about a cause or effort and create awareness or action. Think about motivational speakers and how they can get people encouraged to do something. The same idea is for competent communicators; they have the skill to involve their audience to do something such as protest, vote, or donate. Think about politicians who make speeches and provide so many interesting statements that people are more inclined to vote in a certain direction.

Understands Their Audience

Fourth, competent communicators can understand their audience. Keeping with the same example of politicians, many of them will say things like, “I know what it is like not to be able to feed your family, to struggle to make ends meet, or not to have a job. I know what you are going through. I understand where you are coming from.” These phrases are ways to create a bond between the speaker and the receiver of the message. Competent communicators can empathize and figure out the best way to approach the situation. For instance, if someone you know had a miscarriage and truly has wanted to have kids for a long time, then it would probably be very inconsiderate to say, “just try again.” This comment would be very rude, especially if this person has already tried for a long time to have a child. A competent communicator would have to think about how this person might feel and what words would genuinely be more appropriate to the situation.

Cognitive Complexity

Fifth, knowing how to say the same thing in different ways is called cognitive complexity. You might think that the only way to express affection would be to say, “I love you” or “I care about you.” What other ways could you express affection? This skill is being cognitive complex. Think about a professor you might have had that used different methods to explain the same concept. Your professor might say, “To solve this problem, you might try method A, and if that doesn’t work, you could try method B, and method C is still another way.” This illustrates that you don’t have to say things one way, you could say it in different ways. This helps your audience understand your message better because you provided different ways to comprehend your intended message.

Self-Monitoring

The last characteristic of competent communicators is the ability to monitor yourself. It is also known as self-monitoring. This is the ability to focus on your behavior, and in turn, determine how to behave in the situation. In every speaking situation, most people will have an internal gauge of what they might say next or not say. Some people never give any thought to what they might say to others. These individuals would have low self-monitoring skills, in which what you see is what you get. You could have high self-monitors that pay attention to every little thing, how they stand, where their eyes move, how they gesture, and maybe even how they breathe. They pay attention to these minor details because they are concerned with how the message might come across to others. Competent communicators have a balance of high and low self-monitoring, in which they realize how they might be perceived, but they are not overly focused on all the details of themselves.

Key Takeaways

- Competence involves being both appropriate and effective.

- Appropriateness is what is socially acceptable behaviors, and effective is being able to get your desired outcome.

- Characteristics of competence involve skill, adaptability, involvement, complexity, and empathy.

Exercises

- Who do you think are competent/incompetent communicators? Why?

- How would you rate yourself as a competent speaker? Give a brief impromptu speech, then ask someone to rate you based on the characteristics of competence. Do you agree? Why or why not?

- Using cognitive complexity skills, think about all the ways you can express affection/hatred. Talk about how these ways would be interpreted by others – positively/negatively and why? Does it make if the other person was a different sex, culture, gender, ethnicity, age, or religion? How and why?

1.4 Types of Human Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define Intrapersonal Communication

- Explain Interpersonal Communication

- Elucidate Small Group Communication

- Learn about Public Communication

- Identify Mediated Communication

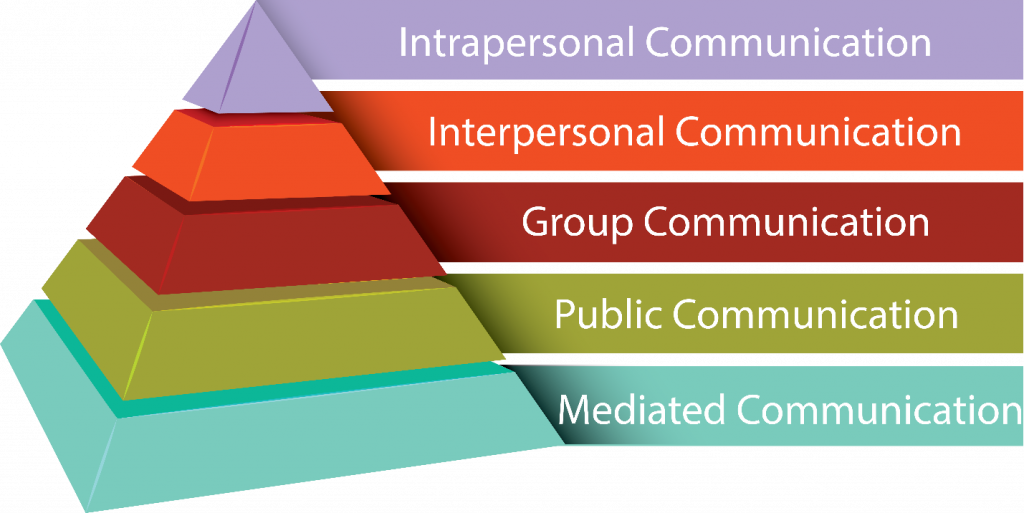

Intrapersonal Communication

Intrapersonal communication refers to communication phenomena that exist within or occurs because of an individual’s self or mind. Some forms of intrapersonal communication can resemble a conversation one has with one’s self. This “self-talk” often is used as a way to help us make decisions or make sense of the world around us. Maybe you’ve gone to the grocery store, and you’re repeating your grocery list over and over in your head to make sure you don’t forget anything. Maybe at the end of the day, you keep a diary or journal where you keep track of everything that has happened that day. Or perhaps you’re having a debate inside your head on what major you should pick. You keep weighing the pros and cons of different majors, and you use this internal debate to help you flesh out your thoughts and feelings on the subject. All three of these examples help illustrate some of what is covered by the term “intrapersonal communication.”

Today scholars view the term “intrapersonal communication” a little more broadly than just the internal self-talk we engage in. Communication scholar Samuel Riccillo primarily discusses intrapersonal communication as a factor of biology.14 Under this perspective, we must think about the biological underpinnings of how we can communicate. The human brain is probably the single most crucial physiological part of human interactions. We know that how people communicate can be greatly impacted by their brains. As such, our definition of intrapersonal communication is broad enough to include both traditional discussions of self-talk and more modern examinations of how the human body helps or hinders our ability to communicate effectively.

Interpersonal Communication

Interpersonal communication, which is what this book is all about, focuses on the exchange of messages between two people. Our days are full of interpersonal communication. You wake up, roll over, and say good morning to your significant other, then you’ve had your first interpersonal interaction of the day. You meet your best friend for coffee before work and discuss the ins and outs of children’s lives; you’re engaging in interpersonal communication again. You go to work and work with a coworker on a project; once again, you’re engaging in interpersonal communication. You then shoot off an email to your babysitter, reminding him to drop by the house at seven so you and your partner can have a night out. Yep, this is interpersonal communication too. You drop by your doctor’s office for your annual physical, and the two of you talk about any health issues, this is also a form of interpersonal communication. You text your child to remind him that he has play practice at 5:00 pm and then needs to come home immediately afterward, you’ve engaged in interpersonal interaction. Hopefully, you’re beginning to realize that our days are filled with tons of interpersonal interactions on any given day.

Some scholars also refer to interpersonal communication as dyadic communication because it involves two people or a dyad. As you saw above, the type of dyad can range from intimate partners, to coworkers, to doctor-patient, to friends, to parent-child, and many other dyadic partnerships. Now we can engage in these interactions through verbal communication, nonverbal communication, and mediated communication. When we use words during our interaction to convey specific meaning, then we’re engaging in verbal communication. Nonverbal communication, on the other hand, refers to a range of other factors that can impact how we understand each other. For example, the facial expressions you have. You could be talking to your best friend over coffee about a coworker and “his problems” while rolling your eyes to emphasize how overly dramatic and nonsensical you find the person. A great deal of how we interpret the verbal message of someone is based on the nonverbal messages sent at the same time. Lastly, we engage in interpersonal interactions using mediated technologies like the cellphone, emailing, texts, Facebook posts, Tweets, etc. Your average professional spends a great deal of her day responding to emails that come from one person, so the email exchange is a form of interpersonal communication.

Small Group Communication

The next type of communication studied by communication scholars, but still important for interpersonal communication, is small group communication. Although different scholars will differ on the exact number of people that make a group, we can say that a group is at least three people interacting with a common goal. Sometimes these groups could be as large as 15, but larger groups become much harder to manage and end up with more problems. One of the hallmarks of a small group is the ability for all the group members to engage in interpersonal interactions with all the other group members.

We engage in small groups throughout our lives. Chances are you’ve engaged in some kind of group project for a grade while you’ve been in school. This experience may have been a great one or a horrible one depending on the personalities within the group, the ability of the group to accomplish the goal, the in-fighting of group members, and many other factors. Whether you like group work or not, you will engage in many groups (some effective and some ineffective) over your lifespan. We’re all born into a family, which is a specific type of group relationship. When you were younger, you may have been in play-groups. As you grew older, you had groups of friends you did things with. As you enter into the professional world, you will probably be on some kind of work “team,” which is just a specialized type of group. In other words, group communication is a part of life.

Public Communication

The next category of communication is called public communication. Public communication occurs when an individual or group of individuals send a specific message to an audience. This one-to-many way of communicating is often necessary when groups become too large to maintain interactions with all group members. One of the most common forms of public communication is public speaking. As I am writing this chapter, we are right in the middle of the primary season for the 2020 Presidential election. People of all political stripes have been attending candidate speeches in record-breaking numbers this year.

The size the audience one speaks to will impact how someone delivers a speech. If you’re to give a speech to ten people, you’ll have the ability to watch all of your audience members and receive real-time feedback as people nod their heads in agreement or disagreement. On the other hand, if you’re speaking to 10,000+ people at once, there is no way for a speaker to watch all of their audience members and get feedback. With a smaller audience, a speaker can adapt their message on the fly as they interpret audience feedback. With a larger audience, a speaker is more likely to deliver a very prepared speech that does not alter based on individual audience members’ feedback. Although this book is not a public speaking book, we would recommend that anyone take a public speaking class because it’s such an essential and valuable skill in the 21st Century. As we are bombarded with more and more messages, being an effective speaker is more important today than ever before.

Mediated Communication

The final type of communication is mediated communication, or the use of some form of technology to facilitate information between two or more people. We already mentioned a few forms of mediated communication when we talked about interpersonal communication: phone calls, emails, text messaging, etc. In each of these cases, mediated technology is utilized to facilitate the share of information between two people.

Most mediated communication occurs because technology functions as the link between someone sending information and someone receiving information. For example, you go online and look up the statistics from last night’s baseball game. The website you choose is the link between you and the reporter who authored the information. In the same way, if you looked up these same results in a newspaper, the newspaper would be the link between you and the reporter who wrote the article. The technology may have changed from print to electronic journalism, but the basic concept is still very much alive.

Today we are surrounded by a ton of different media options. Some common ones include cable, satellite television, the World Wide Web, content streaming services (i.e., Netflix, Hulu, etc.), social media, magazines, voice over internet protocol (VoIP – Skype, Google Hangouts, etc.), and so many others. We have more forms of mediated communication today than we have ever had before in history. Most of us will only experience and use a fraction of the mediated communication technologies that are available for us today.

Key Takeaways

- Intrapersonal communication is communication within yourself.

- Interpersonal communication is the exchange of messages between two people.

- Small group communication consists of three or more individuals.

- Public communication is where you have one speaker and a large audience.

- Mediated communication involves messages sent through a medium to aid the message.

Exercises

- What are some benefits to mediated communication? What are some drawbacks? How does it impact the message?

- Which type of communication would be the most difficult/easiest to study and why?

- As a group, think of some possible research studies for each type of communication? Why would it be important to study?

1.5 Understanding Mindful Communication

Learning Objectives

The words “mindful,” “mindfulness,” and “mindlessness” have received a lot of attention both within academic circles and outside of them. Many people hear the word “mindful” and picture a yogi sitting on a mountain peak in lotus position meditating while listening to the wind. And for some people, that form of mindfulness is perfectly fine, but it’s not necessarily beneficial for the rest of us. Instead, mindfulness has become a tool that can be used to improve all facets of an individual’s life. In this section, we’re going to explore what mindfulness and develop an understanding of what we will call in this book “mindful communication.”

Defining Mindfulness

As such, there are several different definitions that have appeared trying to explain what these terms mean. Let’s look at just a small handful of definitions that have been put forward for the term “mindfulness.”

- “[M]indfulness as a particular type of social practice that leads the practitioner to an ethically minded awareness, intentionally situated in the here and now.”15

- “[D]eliberate, open-minded awareness of moment-to-moment perceptible experience that ordinarily requires gradual refinement by means of systematic practice; is characterized by a nondiscursive, nonanalytic investigation of ongoing experience; is fundamentally sustained by such attitudes as kindness, tolerance, patience, and courage; and is markedly different from everyday modes of awareness.”16

- “[T]he process of drawing novel distinctions… The process of drawing novel distinctions can lead to a number of diverse consequences, including (1) a greater sensitivity to one’s environment, (2) more openness to new information, (3) the creation of new categories for structuring perception, and (4) enhanced awareness of multiple perspectives in problem solving.”17

- “Mindfulness is a flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context, with an open, nonjudgmental orientation to experience.”18

- “[F]ocusing one’s attention in a nonjudgmental or accepting way on the experience occurring in the present moment [and] can be contrasted with states of mind in which attention is focused elsewhere, including preoccupation with memories, fantasies, plans, or worries, and behaving automatically without awareness of one’s actions.”19

- “[T]he focus of a person’s attention is opened to admit whatever enters experience, while at the same time, a stance of kindly curiosity allows the person to investigate whatever appears, without falling prey to automatic judgment or reactivity.”20

- “Paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.”21

- “Mindfulness is the practice of returning to being centered in this living moment right now and right here, being openly and kindly present to our own immediate mental, emotional, and bodily experiencing, and without judgment.”22

- “[A]wareness of one’s internal states and surroundings. The concept has been applied to various therapeutic interventions—for example, mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and mindfulness meditation—to help people avoid destructive or automatic habits and responses by learning to observe their thoughts, emotions, and other present-moment experiences without judging or reacting to them.”23

- “[A] multifaceted construct that includes paying attention to present-moment experiences, labeling them with words, acting with awareness, avoiding automatic pilot, and bringing an attitude of openness, acceptance, willingness, allowing, nonjudging, kindness, friendliness, and curiosity to all observed experiences.”24

What we generally see within these definitions of the term “mindfulness” is a spectrum of ideas ranging from more traditional Eastern perspectives on mindfulness (usually stemming out of Buddhism) to more Western perspectives on mindfulness arising out of the pioneering research conducted by Ellen Langer.25

Towards a Mindfulness Model

Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson, take the notion of mindfulness a step farther and try to differentiate between mindful awareness and mindful practice:

(a) Mindful awareness, an abiding presence or awareness, a deep knowing that contributes to freedom of the mind (e.g. freedom from reflexive conditioning and delusion) and (b) mindful practice, the systematic practice of intentionally attending in an open, caring, and discerning way, which involves both knowing and shaping the mind. To capture both aspects we define the construct of mindfulness as “the awareness that arises through intentionally attending in an open, caring, and discerning way.”26

The importance of this perspective is that Shapiro and Carlson recognize that mindfulness is a cognitive, behavioral, and affective process. So, let’s look at each of these.

Mindful Awareness

First, we have the notion of mindful awareness. Most of what mindful awareness is attending to what’s going on around you at a deeper level. Let’s start by thinking about awareness as a general concept. According to the American Psychological Association’s dictionary, awareness is “perception or knowledge of something.”27 Awareness involves recognizing or understanding an idea or phenomenon. For example, take a second and think about your breathing. Most of the time, we are not aware of our breathing because our body is designed to perform this activity for us unconsciously. We don’t have to remind ourselves to breathe in and out with every breath. If we did, we’d never be able to sleep or do anything else. However, if you take a second and focus on your breathing, you are consciously aware of your breathing. Most breathing exercises, whether for acting, meditation, public speaking, singing, etc., are designed to make you aware of your breath since we are not conscious of our breathing most of the time.

Mindful awareness takes being aware to a different level. Going back to our breathing example. Take a second and focus again on your breathing. Now ask yourself a few questions:

- How do you physically feel while breathing? Why?

- What are you thinking about while breathing?

- What emotions do you experience while breathing?

The goal then of mindful awareness is to be consciously aware of what you’re physical presence, cognitive processes, and emotional state while engaged in an activity. More importantly, it’s not about judging these; it’s simply about being aware and noticing.

Mindful Practice

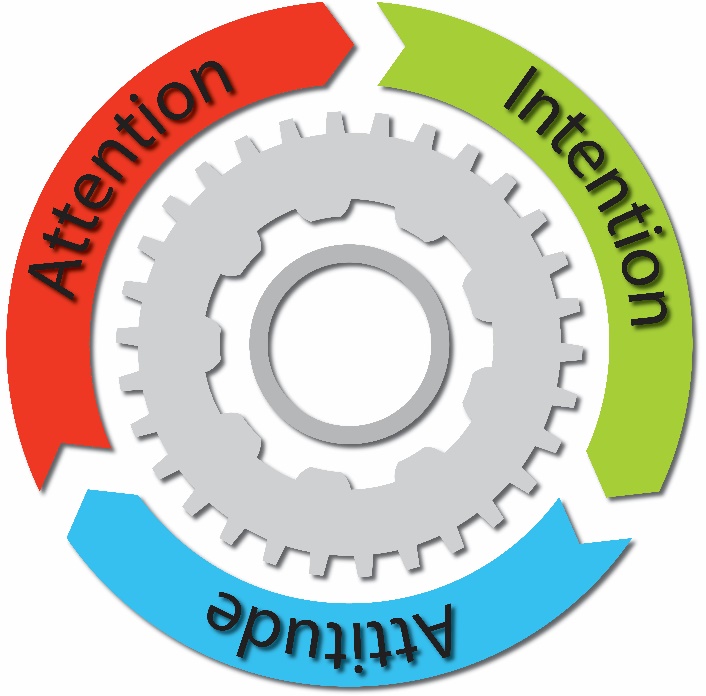

Mindful practice, as described by Shapiro and Carlson, is “the conscious development of skills such as greater ability to direct and sustain our attention, less reactivity, greater discernment and compassion, and enhanced capacity to disidentify from one’s concept of self.”28 To help further explore the concept of mindful practice, Shauna Shapiro, Linda Carlson, John Astin, and Benedict Freedman proposed a three-component model (Figure 1.7): attention, intention, and attitude.29

Attention

“Attention involves attending fully to the present moment instead of allowing ourselves to become preoccupied with the past or future.”30 Essentially, attention is being aware of what’s happening internally and externally moment-to-moment. By internally, we’re talking about what’s going on in your head. What are your thoughts and feelings? By externally, what’s going on in your physical environment. To be mindful, someone must be able to focus on the here and now. Unfortunately, humans aren’t very good at being attentive. Our minds tend to wander about 47% of the time.31 Some people say that humans suffer from “monkey mind,” or the tendency of our thoughts to swing from one idea to the next. 32 As such, being mindful is partially being aware of when our minds start to shift to other ideas and then refocusing ourselves.

Intention

“Intention involves knowing why we are doing what we are doing: our ultimate aim, our vision, and our aspiration.”33 So the second step in mindful practice is knowing why you’re doing something. Let’s say that you’ve decided that you want to start exercising more. If you wanted to engage in a more mindful practice of exercise, the first step would be figuring out why you want to exercise and what your goals are. Do you want to exercise because you know you need to be healthier? Are you exercising because you’re worried about having a heart attack? Are you exercising because you want to get a bikini body before the summer? Again, the goal here is simple, be honest with ourselves about our intentions.

Attitude

“Attitude, or how we pay attention, enables us to stay open, kind, and curious.”34 Essentially, we can all bring different perspectives when we’re attending to something. For example, “attention can have a cold, critical quality, or an openhearted, curious, and compassionate quality.”35 As you can see, we can approach being mindful from different vantage points, so the “attitude with which you undertake the practice of paying attention and being in the present is crucial”36 One of the facets of mindfulness is being open and nonjudging, so having that “cold, critical quality” is antithetical to being mindful. Instead, the goal of mindfulness must be one of openness and non-judgment.

So, what types of attitudes should one attempt to develop to be mindful? Daniel Siegel proposed the acronym COAL when thinking about our attitudes: curiosity, openness, acceptance, and love.37

- C stands for curiosity (inquiring without being judgmental).

- O stands for openness (having the freedom to experience what is occurring as simply the truth, without judgments).

- A stands for acceptance (taking as a given the reality of and the need to be precisely where you are).

- L stands for love (being kind, compassionate, and empathetic to others and to yourself).38

Jon Kabat-Zinn, on the other hand, recommends seven specific attitudes that are necessary for mindfulness:

- Nonjudging: observing without categorizing or evaluating.

- Patience: accepting and tolerating the fact that things happen in their own time.

- Beginner’s-Mind: seeing everything as if for the very first time.

- Trust: believing in ourselves, our experiences, and our feelings.

- Non-striving: being in the moment without specific goals.

- Acceptance: seeing things as they are without judgment.

- Letting Go: allowing things to be as they are and getting bogged down by things we cannot change.

Neither Siegel’s COAL or Kabat-Zinn’s seven attitudes is an exhaustive list of attitudes that can be important to mindfulness. Still, they give you a representative idea of the types of attitudes that can impact mindfulness. Ultimately, “the attitude that we bring to the practice of mindfulness will to a large extent determine its long-term value. This is why consciously cultivating certain attitudes can be very helpful… Keeping particular attitudes in mind is actually part of the training itself.”39

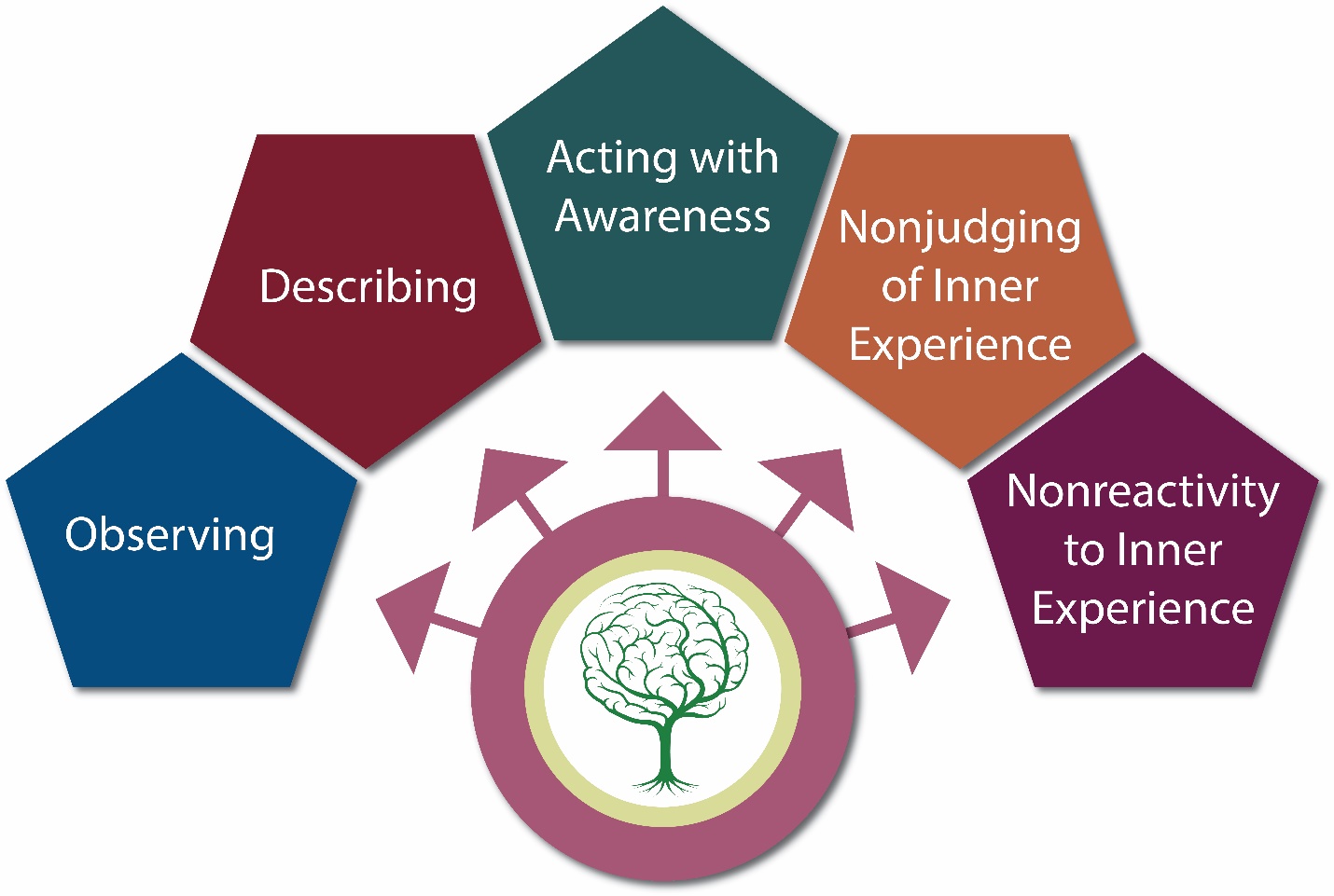

Five Facets of Mindfulness

From a social scientific point-of-view, one of the most influential researchers in the field of mindfulness has been Ruth Baer. Dr. Baer’s most significant contribution to the field has been her Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, which you can take on her website. Dr. Baer’s research concluded that there are five different facets of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience (Figure 1.8).40

Observing

The first facet of mindfulness is observing, or “noticing or attending to a variety of internal or external phenomena (e.g., bodily sensations, cognitions, emotions, sounds).”41 When one is engaged in mindfulness, one of the basic goals is to be aware of what is going on inside yourself and in the external environment. Admittedly, staying in the moment and observing can be difficult because our minds are always trying to shift to new topics and ideas (again that darn monkey brain).

Describing

The second facet of mindfulness is describing, or “putting into words observations of inner experiences of perceptions, thoughts, feelings, sensations, and emotions.”42 The goal of describing is to stay in the moment by being detailed focused on what is occurring. We should note that having a strong vocabulary does make describing what is occurring much easier.

Acting with Awareness

The third facet of mindfulness is acting with awareness, or “engaging fully in one’s present activity rather than functioning on automatic pilot.” 43 When it comes to acting with awareness, it’s important to focus one’s attention purposefully. In our day-to-day lives, we often engage in behaviors without being consciously aware of what we are doing. For example, have you ever thought about your routine for showering? Most of us have a pretty specific ritual we use in the shower (the steps we engage in as we shower). Still, most of us do this on autopilot without really taking the time to realize how ritualized this behavior is.

Nonjudging of Inner Experience

The fourth facet of mindfulness is the nonjudging of inner experience, which involves being consciously aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and attitudes without judging them. One of the hardest things for people when it comes to mindfulness is not judging themselves or their inner experiences. As humans, we are pretty judgmental and like to evaluate most things as positive or negative, good or bad, etc.… However, one of the goals of mindfulness is to be present and aware. As soon as you start judging your thoughts, feelings, and attitudes, you stop being present and become focused on your evaluations and not your experiences.

Nonreactivity to Inner Experience

The last facet of mindfulness is nonreactivity to inner experience “Nonreactivity is about becoming consciously aware of distressing thoughts, emotions, and mental images without automatically responding to them.”44 Nonreactivity to inner experience is related to the issue of not judging your inner experience, but the difference is in our reaction. Nonreactivity involves taking a step back and evaluating things from a more logical, dispassionate perspective. Often, we get so bogged down in our thoughts, emotions, and mental images that we end up preventing ourselves from engaging in life.

For example, one common phenomenon that plagues many people is imposter syndrome, or perceived intellectual phoniness.45 Some people, who are otherwise very smart and skilled, start to believe that they are frauds and are just minutes away from being found out. Imagine being a brilliant brain surgeon but always afraid someone’s going to figure out that you don’t know what you’re doing. Nonreactivity to our inner experience would involve realizing that we have these thoughts but not letting them influence our actual behaviors. Admittedly, nonreactivity to inner experience is easier described than done for many of us.

Mindfulness Activity

As a simple exercise to get you started in mindfulness, we want to spend 15 minutes coloring. Yep, you heard that right. We want you to color. Now, this may seem a bit of an odd request, but research has shown us that coloring is an excellent activity for increasing mindfulness, reducing anxiety/stress, and increasing your mood.46,47,48,49 Coloring also has direct effects on our physiology by reducing our heart rates and blood pressure.50 Coloring also helps college students reduce their test anxiety.51 For this exercise, we’ve created an interpersonal communication mandala-inspired coloring page. According to Lawrence Shapiro, author of Mindful Coloring: A Simple and Fun Way to Reduce Stress in Your Life, here are the basic steps you should take to engage in mindful coloring:

As a simple exercise to get you started in mindfulness, we want to spend 15 minutes coloring. Yep, you heard that right. We want you to color. Now, this may seem a bit of an odd request, but research has shown us that coloring is an excellent activity for increasing mindfulness, reducing anxiety/stress, and increasing your mood.46,47,48,49 Coloring also has direct effects on our physiology by reducing our heart rates and blood pressure.50 Coloring also helps college students reduce their test anxiety.51 For this exercise, we’ve created an interpersonal communication mandala-inspired coloring page. According to Lawrence Shapiro, author of Mindful Coloring: A Simple and Fun Way to Reduce Stress in Your Life, here are the basic steps you should take to engage in mindful coloring:

- Set aside 5 to 15 minutes to practice mindful coloring.

- Find a time and place where you will not be interrupted.

- Gather your materials to do your coloring and sit comfortably at a table. You may want to set a time for 5 to 15 minutes. You should try and continue your mindful practice until the alarm goes off.

- Chose any design you like and begin coloring wherever you like.

- As you color, start paying attention to your breathing. You will probably find that your breathing is becoming slower and deeper, but you don’t have to try to relax. In fact, you don’t have to try and do anything. Just pay attention to the design, to your choice of colors, and to the process of coloring.52

After completing this simple exercise, answer the following questions:

- How did it feel to just focus on coloring?

- Did you find your mind wandering to other topics while coloring? If so, how did you refocus yourself?

- How hard would it be to have that same level of concentration when you’re talking with someone?

Interpersonal Communication and Mindfulness

For our purposes within this book, we want to look at issues related to mindful interpersonal communication that spans across these definitions. Although the idea of “mindfulness” and communication is not new,53,54 Judee Burgoon, Charles Berger, and Vincent Waldron were three of the first researchers to formulate a way of envisioning mindfulness and interpersonal communication.55 As with the trouble of defining mindfulness, there are different perspectives on what mindful communication is as well. Let’s look at three fairly distinct definitions:

- “Communication that is planful, effortfully processed, creative, strategic, flexible, and/or reason-based (as opposed to emotion-based) would seem to qualify as mindful, whereas communication that is reactive, superficially processed, routine, rigid, and emotional would fall toward the mindless end of the continuum.” 56

- “Mindful communication including mindful speech and deep listening are important. But we must not overlook the role of compassion, wisdom, and critical thinking in communication. We must be able empathize with others to see things from their perspective. We should not continue with our narrow prejudices so that we can start meaningful relationships with others. We can then come more easily to agreement and work together.”57

- “Mindful communication includes the practice of mindful presence and encompasses the attributes of a nonjudgmental approach to [our interactions], staying actively present in the moment, and being able to rapidly adapt to change in an interaction.”58

As you can see, these perspectives on mindful communication align nicely with the discussion we had in the previous section related to mindfulness. However, there is not a single approach to what is “mindful communication.” Each of these definitions can help us create an idea of what mindful communication is. For our purposes within this text, we plan on taking a broad view of mindful communication that encompasses both perspectives of secular mindfulness and non-secular mindfulness (primarily stemming out of the Buddhist tradition). As such, we define mindful communication as the process of interacting with others while engaging in mindful awareness and practice. Although more general than the definitions presented above, we believe that aligning our definition with mindful awareness and practice is beneficial because of the Shapiro and Carlson’s existing mindfulness framework.59

However, we do want to raise one note about the possibility of mindful communication competence. From a communication perspective, it’s entirely possible to be mindful and not effective in one’s communication. Burgoon, Berger, and Waldron wrote, “without the requisite communication skills to monitor their actions and adapt their messages, without the breadth of repertoire that enables flexible, novel thought processes to translate into creative action, a more mindful state may not lead to more successful communication.”60 As such, there has to be a marriage between mindfulness and communication skills. This book aims to provide a perspective that enhances both mindfulness and interpersonal communication skills.

Key Takeaways

- The term “mindfulness” encompasses a range of different definitions from the strictly religious (primarily Buddhist in nature) to the strictly secular (primarily psychological in nature). Simply, there is not an agreed upon definition.

- Shauna Shapiro and Linda Carlson separate out mindful awareness from mindful practice. Mindful practice involves three specific behaviors: attention (being aware of what’s happening internally and externally moment-to-moment.), intention (being aware of why you are doing something), and attitude (being curious, open, and nonjudgmental).